China is set to play a major major major role in this round of infrastructure spending in Thailand。

Fast train coming

Fast train coming

Oct 12th 2013, 9:45 by T.J. | BANGKOK

IN THE grand concourse of Bangkok’s main train station, Hua Lamphong, the future is on display. Hulking billboards announce the impending arrival of high-speed trains and an age of international connectedness. For those who happen not to pass through the capital, a two-month road show called “Building the Thai Future 2020” is touring the provinces to keep people abreast of the government’s plans for the country’s railways and other infrastructure.

In the past 20 years, train passenger numbers have collapsed from 88m per year to 46m. The government, it would seem, is no longer willing to tolerate the slide.

The big idea is to spend 2 trillion baht ($64 billion) by 2020 towards upgrading the country’s creaking infrastructure. Another 3 trillion baht will come due as interest on the loans, accumulating over the next 50 years. It aims to fulfil a favourite dream of Thailand’s political class: To make the country the keystone of mainland South-East Asia. (WikiLeaks reveals that in 1973 Thai mandarins joined Edward Teller, an American nuclear nut, in the fantasy of using Hiroshima-sized bombs to blast a canal from the South China Sea to the Indian Ocean.) The “Future 2020” plan will be the first state-led push to build anything on a truly grand scale since the crash of 1997, which ended a monumental construction boom.

This will also be a stimulus programme, so large as to trigger labour migration. The new works should create 500,000 jobs—more than there are unemployed people in Thailand, the only country in Asia that enjoys an effective rate of full employment. The timing is convenient for the government, even if there are already jobs aplenty. Elections must be held by 2015 and a pot of off-budget spending worth nearly one-fifth of the country’s GDP is a nice thing for the politicians to have handy, just when well-placed allies and voters need reassurance that their loyalty is appreciated.

Yingluck Shinawatra, the prime minister, has embarked on a mission to raise the cash. A fortnight ago parliament passed a bill that permits the government to take on off-budget debt equivalent to the combined annual economic output of Vietnam, Myanmar, Laos and Cambodia.

The centrepiece of the spending plan is a network of high-speed railway lines to connect the country’s four main regions with Bangkok. (Smaller dollops of cash are to be earmarked for roads and ports.) Two of the lines are part of a broader plan to link China’s Yunnan province with Singapore. One of these runs right through Thailand’s north-east, which is the political base of Ms Yingluck’s family; the other connects the capital with Thailand’s second city, Chiang Mai, which is their actual hometown. The economic rationale is to cut transport costs everywhere, bearing in mind that almost twice as many Thais live in the countryside as in the cities; Thailand is still among the least urbanised countries in Asia. Another objective of the beefed-up rail network is to keep migrant workers in the cities connected to their roots.

The Democrat Party, at the head of the opposition, agrees with the general thrust of the bill—but not with its financing. The Democrats have come up with their own 2 trillion baht plan, which would use the annual budget (rather than emergency legislation) for less-costly trains and then leave money in the pot for education, health and irrigation. Korn Chatikavanij, an opposition politician and former finance minister, says the government’s bill violates “the main tenets of fiscal prudence”. He says his party will contest it in the constitutional court before it is sent to the palace for royal endorsement.

This call for fiscal prudence is not what the opposition needs if it is to change the electoral map in its favour. As it stands, districts are heavily tilted towards the Pheu Thai party, the third incarnation of a party founded by Ms Yingluck’s exiled brother. The close relationship between the Thai state and rural Thailand—where Ms Yingluck’s family has its base—owes more to generosity than to prudence.

Largesse and the culture of easy credit are what worry the Bank of Thailand, the central bank, and many other economists too. According to Standard Chartered, a private bank, household borrowing as a share of national income now stands at 68% of Thailand’s GDP, much higher than in bigger Asian countries, such as China (20%), India (18%) and Indonesia (17%).

But the spending bill is not likely to create either a monstrous level of public debt or a household-debt problem. The public debt, at 45% of Thailand’s GDP, is still very low. And unlike most Asian countries, Thailand has a vast stock of assets—land and property—against which people can borrow. And so looking at rising debt-to-income ratios, as everyone in the debate appears to be doing, is to miss an important part of the story. Robert Townsend, an economist at MIT, runs the Townsend Thai Project, the largest and longest-running survey of households in the developing world. He reckons that average debt-to-asset ratios in rural Thailand are relatively low and have actually been falling since 2006.

The case against the infrastructure plan, which everyone agrees is needed in principle, starts not with debt but with corruption. Thailand’s government agencies are notorious for their procurement contracts’ lack of transparency. The slipshod State Railway of Thailand, which was founded by King Rama V as a non-profit entity (and anyway run in a manner that precludes the possibility of turning a profit), is supposed to handle more than a trillion of the baht to be raised.

China has been looking for reassurances from Ms Yingluck’s government that Thailand’s future really can be expected to pull into the station by 2020. That is when China plans to connect Vientiane, the capital of Laos, to Thailand. In the meantime China plans to sink $6.2 billion into a passenger and freight railway that will run from Kunming to Vientiane, tunnelling through 196km of mountains to get there. A Swiss man based in Vientiane remarks that in his country a project on this scale would be called a Jahrhundertprojekt, “a project of the century”. China’s clock however, runs faster: they are giving it five years.

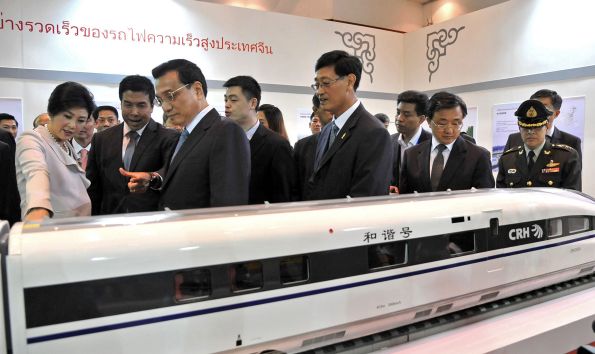

On October 12th Ms Yingluck and Li Keqiang (pictured facing one another, at the left), the prime minister of China, stood together at a press event, to gaze at a model train and then into the future of high-speed railway magic—on a large screen, in Bangkok.

Infrastructure spending in Thailand: Fast train coming | The Economist