LeveragedBuyout

SENIOR MEMBER

- Joined

- May 16, 2014

- Messages

- 1,958

- Reaction score

- 60

- Country

- Location

So much for the end of the USD as the global reserve currency.

---

The Return of the Currency Wars - Real Time Economics - WSJ

ByDavid Wessel

When a country’s economy grows too slowly, the standard short-term remedies are to increase government spending, cut taxes or reduce interest rates. When none of those options is available, governments often resort to pushing down their currencies to make their exports more attractive to foreigners (and, these days, to push up import prices and thus bring inflation back up to desired levels).

When the world economy is sputtering, and every big country increases spending, cuts taxes and reduces interest rates, the global economy benefits from the increase in demand. That’s the story of 2009.

But when individual countries lean heavily on pushing their currencies down, that tends to shift demand from one place to another rather than increasing the total. That is a “currency war.” And we may be on the verge of one. Last time, the emerging markets were doing the complaining; this time, it may be the U.S. (OK, I’m oversimplifying, but only a bit.)

Japan has already managed to depreciate its currency. The yen is at a six-year low against the dollar. There is a fine line between pursuing expansionary monetary policy which works (in part) by reducing a country’s currency, and making currency depreciation a primary goal. The U.S. and Europe have tolerated the sinking yen largely because they saw it as part of Prime MinisterShinzo Abe’s broader effort to resuscitate the Japanese economy.

Now the spotlight is shifting to Europe. Europe is growing painfully slowly, if at all. Unemployment in the countries that share the euro is 11.5%. Among the under-25 crowd, nearly one in four is out of work.

Standard economics, the sort pushed by the International Monetary Fund, among others, suggests that while Europe addresses its much-discussed structural impediments to economic growth, it also pursue low taxes, more government spending and more expansionary monetary policy. And since short-term interest rates are already at zero, that means something akin to theFederal Reserve’s quantitative easing, the purchase of huge amounts of assets by the central bank to get more money into the economy, rekindle inflation (now at 0.3% in Europe) and nudge investors into private-sector loans, bonds and stocks.

But what appears to be economically necessary is not politically possible. Germany is the heavyweight in the eurozone. It wants to keep the pressure on southern Europe to reform labor and other regulations, to work harder and to reduce their debts so it won’t bless more expansionary fiscal policy. And for those reasons, plus its historic anxiety about inflation no matter what the circumstances, it appears opposed to more aggressive European Central Bank action – or, at the very least, it is slowing the ECB’s efforts to move in that direction.

The politics are treacherous. As Europe leaders fumble and struggle to reach consensus, the public backlash against austerity and slow growth is building. Euro-skeptic Marie Le Pen (“I don’t want this European Soviet Union,” she told der Spiegel Online in June) has a shot at becoming the next president of France.

So what’s the ECB to do? Push down the euro to try to juice the eurozone’s exports. That appears to be one of ECB President Mario Draghi’s current objectives, and it’s one he can achieve with words even if he can’t get his policy council to agree on printing a lot of euros. It certainly is appealing to the French, who’ve long seen the currency as a useful economic instrument.

And the markets are getting the message. The euro, which was trading above $1.38 for most of the spring, has fallen below $1.30 – and Goldman Sachs economists predict it’ll fall to $1.15 by the end of 2015.

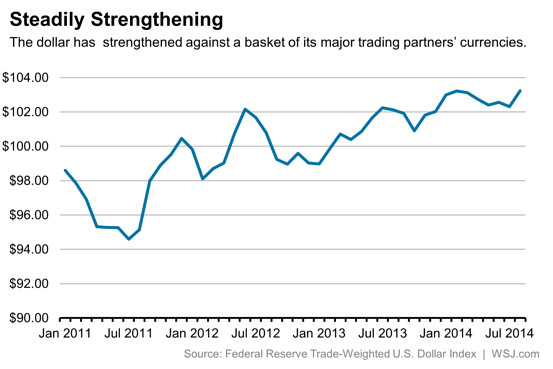

For now this isn’t a big threat to the U.S. economy. The U.S. dollar has been strengthening for some time, initially because nervous investors were looking for safety and more recently because markets expect the Fed to begin raising interest rates from rock-bottom levels next year, well before the ECB does.

Although there are always manufacturers complaining that the dollar is hurting their exports and there are long-standing complaints about China’s manipulation of its currency to favor its exports, the dollar hasn’t really been a big political or economic issue in the U.S. lately.

Perhaps because there has been so much else to worry about; perhaps because the dollar’s attractiveness has helped the U.S. Treasury lure foreigners to lend billions of dollars at very low rates. U.S. exports have been growing; they contributed 1.3 percentage points to the 4.2% annualized increase in gross domestic product in the second quarter. But that could change if Japan and Europe continue to nudge their currencies down as a substitute for economic policies more friendly to global economic growth.

---

The Return of the Currency Wars - Real Time Economics - WSJ

- September 15, 2014, 10:26 AM ET

ByDavid Wessel

When a country’s economy grows too slowly, the standard short-term remedies are to increase government spending, cut taxes or reduce interest rates. When none of those options is available, governments often resort to pushing down their currencies to make their exports more attractive to foreigners (and, these days, to push up import prices and thus bring inflation back up to desired levels).

When the world economy is sputtering, and every big country increases spending, cuts taxes and reduces interest rates, the global economy benefits from the increase in demand. That’s the story of 2009.

But when individual countries lean heavily on pushing their currencies down, that tends to shift demand from one place to another rather than increasing the total. That is a “currency war.” And we may be on the verge of one. Last time, the emerging markets were doing the complaining; this time, it may be the U.S. (OK, I’m oversimplifying, but only a bit.)

Japan has already managed to depreciate its currency. The yen is at a six-year low against the dollar. There is a fine line between pursuing expansionary monetary policy which works (in part) by reducing a country’s currency, and making currency depreciation a primary goal. The U.S. and Europe have tolerated the sinking yen largely because they saw it as part of Prime MinisterShinzo Abe’s broader effort to resuscitate the Japanese economy.

Now the spotlight is shifting to Europe. Europe is growing painfully slowly, if at all. Unemployment in the countries that share the euro is 11.5%. Among the under-25 crowd, nearly one in four is out of work.

Standard economics, the sort pushed by the International Monetary Fund, among others, suggests that while Europe addresses its much-discussed structural impediments to economic growth, it also pursue low taxes, more government spending and more expansionary monetary policy. And since short-term interest rates are already at zero, that means something akin to theFederal Reserve’s quantitative easing, the purchase of huge amounts of assets by the central bank to get more money into the economy, rekindle inflation (now at 0.3% in Europe) and nudge investors into private-sector loans, bonds and stocks.

But what appears to be economically necessary is not politically possible. Germany is the heavyweight in the eurozone. It wants to keep the pressure on southern Europe to reform labor and other regulations, to work harder and to reduce their debts so it won’t bless more expansionary fiscal policy. And for those reasons, plus its historic anxiety about inflation no matter what the circumstances, it appears opposed to more aggressive European Central Bank action – or, at the very least, it is slowing the ECB’s efforts to move in that direction.

The politics are treacherous. As Europe leaders fumble and struggle to reach consensus, the public backlash against austerity and slow growth is building. Euro-skeptic Marie Le Pen (“I don’t want this European Soviet Union,” she told der Spiegel Online in June) has a shot at becoming the next president of France.

So what’s the ECB to do? Push down the euro to try to juice the eurozone’s exports. That appears to be one of ECB President Mario Draghi’s current objectives, and it’s one he can achieve with words even if he can’t get his policy council to agree on printing a lot of euros. It certainly is appealing to the French, who’ve long seen the currency as a useful economic instrument.

And the markets are getting the message. The euro, which was trading above $1.38 for most of the spring, has fallen below $1.30 – and Goldman Sachs economists predict it’ll fall to $1.15 by the end of 2015.

For now this isn’t a big threat to the U.S. economy. The U.S. dollar has been strengthening for some time, initially because nervous investors were looking for safety and more recently because markets expect the Fed to begin raising interest rates from rock-bottom levels next year, well before the ECB does.

Although there are always manufacturers complaining that the dollar is hurting their exports and there are long-standing complaints about China’s manipulation of its currency to favor its exports, the dollar hasn’t really been a big political or economic issue in the U.S. lately.

Perhaps because there has been so much else to worry about; perhaps because the dollar’s attractiveness has helped the U.S. Treasury lure foreigners to lend billions of dollars at very low rates. U.S. exports have been growing; they contributed 1.3 percentage points to the 4.2% annualized increase in gross domestic product in the second quarter. But that could change if Japan and Europe continue to nudge their currencies down as a substitute for economic policies more friendly to global economic growth.