Queen Elissar, a princess of Tyre founded Carthage. Her metropolis rose in its high-noon to be called a "shining city," ruling 300 other cities around the western Mediterranean and leading the Phoenician Punic world.

Elissa/Elissar or Dido; the Queen of Carthage

Background and Origin

In the harbor of ancient Tyre in Phoenicia, the fisherman chant "Ela--eee--sa, Ela--eee--sa," as they haul in their nets. They cannot say why; maybe it's for luck, or maybe it's a lament for their princess who left her homeland never to return.

Elissar or Elissa (Elishat, in Phoenician) was a princess of Tyre. She was Jezebel's grandniece Princess Jezebel of Tyre was Queen of Israel. Her brother, Pygmalion king of Tyre, murdered her husband, the high priest. She escaped tyranny in her country and founded Carthage and thereafter its Phoenician Punic dominions. Carthage became later a great center of the western Mediterranean in its high-noon. One of its most famous sons was Hannibal who defied Rome.

Details of her life are sketchy and confusing, however, following is what one can deduce from various sources. According to Justin, Princess Elissar was the daughter of King Matten or Muttoial of Tyre (Belus II of classical literature). After his death, the throne was jointly bequeathed to her and her brother, Pygmalian. She was married to her uncle Acherbas (Sychaeus of classical literature), High Priest of Melqart and a man of authority and riches like that of a king. Tyrannical Pygmalion, a lover of gold and intrigue, was eager to be acquire the authority and fortune of Acherbas. He assassinated him in the Temple and kept his evil deed a secret for a long time from his sister. He cheated her with fictions about his death. Meanwhile, the people of Tyre were pressing for a single sovereign that caused dissensions within the royal family.

Legend has it that the ghost of Acherbas appeared to Elissar in a dream and told her what had happened to him. Further, he told her where she could find his treasure. Further, he advised her to leave Tyre for fear of her life. Elissar and her supporters seized the treasure of gold. However, because she was threatened and frightened, Elissar decided to trick and flee her brother.

Not to awaken her brother's suspicions, she made it known that she wanted to travel and send him offerings. Acherbas approved thinking that Elissar would send him riches. He provided her with ships. During the night, Elissar had her treasures of gold hidden in the hold of the ships and had bags filled with sands laid out onboard, also. Once at sea she had the sand bags thrown overboard, calling that an offering in memory of her murdered husband. The servants feared that loss of the treasure would enrage the king against and they would suffer his reprisal. Consequently, they decided to pay allegiance to Elissar and accompany her on a voyage. Elissar's supports, as well as additional senators and priests of Melqart joined the group. Consequently, they left the country in secret, leaving behind their homeland forever.

They traveled first to the island of Cyprus to get supplies for a longer journey. There, twenty virgins who were devoted to serve in the Temple of Ashtarte (Venus) as vestal virgins, renounced their vows, and married in the Tyrinian entourage that accompanied the princess. Thereafter, Elissar and her company, "the vagrants" (a.k.a. Dido the ?wanderer?) faced the open sea in search for a new place to settle.

Founding of Carthage

Very early in ancient history, Phoenician sailors had visited the far corners of the Mediterranean sea and established commercial relations with the local people. Sidonian Phoenicians had established trading posts in the 16th century B.C. at Utica which is relatively close to where Carthage was later to be established. Their main objective was commercial to compete with their Tyrinian Phoenician brothers who had a colony at Utica. Archaeological evidence of the early settlements have been found. The position of Utica towards Carthage was precisely that of Sidon towards Tyre. It was the more ancient city of the two, and it preserved a certain kind of position without actual power. Carthage and Utica competed, like Tyre and Sidon and they were at one time always spoken of together.

Elissar and her Tyrinian entourage, including her priests and temple maidens of Ashtarte, crossed the length of the Mediterranean in several ships and settled the shores of what's today modern Tunisia. Her expedition came and negotiated with the local inhabitants on purchasing a piece of land. Sailing into the Gulf of Tunis she spied a headland that would be the perfect spot for a city and chose the very site called Cambe or Caccabe which was an ancient Sidonian Phoenician trading post. However, some records indicate that the goddess Tanit (Juno in Latin) indicated the spot were to found the city. The natives there weren't too happy about the newcomers, but Elissar was able to make a deal with their king Japon: she promised him a fair amount of money and rent for many years for as much land as she could mark out with a bull's skin.

The king thought he was getting the better end of the deal, but he soon noticed that the woman he was dealing with was smarter than he had expected. This purchase contained some intrigue while the size of the land was thought not to exceed a "Bull's Hide," it actually was a lot larger then ever thought. The trick she and her expedition employed was that they cutup a bull's hide into very thin which they sewed together into one long string. Then they took the seashore as one edge for the piece of land and laid the skin into a half-circle. Consequently, Elissar and her company got a much bigger piece of land than the king had thought possible. The Carthaginians continued to pay rent for the land until the 6th century BC. That hilltop today is called the "Byrsa." Byrsa means "ox hide." However, there is some confusion over the word; some believe that it refers to the Phoenician word borsa which means citadel or fortress.

King Japon was very impressed by Elissar's great mathematical talents and asked her to marry him. She refused, so he had a huge university built, hoping to find another young lady with similar talents instead. On that "carved" site, Elissar and her colonial entourage founded a new city ca. 814 BC. They called it 'Qart-Haddasht' (Carthage) which comes from two Phoenician words that mean 'New Land." In memory of their Tyrinian origin, the people of Carthage paid an annual tribute to the temple of Melqart of Tyre in Phoenicia.

The city of Carthage slowly gained its independence from Tyre though it was initially controlled by its own magistrates carrying the title of suffetes It kept close links with Tyre, the metropolis, until 332 BC.

The colonization of Carthage, and thereafter, the territories around the western Mediterranean were a very successful endeavor that gave rise to the powerful Phoenician Punic dominions. A western Mediterranean Phoenicians become known as Carthaginians. Later, Punic, a name used by the Romans to refer to western Mediterranean Phoenicians, was applied to all Carthaginians and the 300 city states and lands they came to occupy.

The Carthaginian were very captivated with their queen and many believe that she was thought to be a goddess who came to be known Tanit.

Elissar's Problem

This section has been omitted due to copyright restrictions. Please read it on the source page if you are so inclined.

The Date of Founding Carthage

With regard to Phoenician history, we depend on the reports of Greek and Roman authors who were not kindly disposed towards them. A grim struggle was waged for centuries between the Greeks and Romans on the one hand, and the Phoenicians and their western offshoot, the Carthaginians, on the other, in which the prize was nothing less than the political and commercial control of the Mediterranean. It began as early as the Orientalizing period of the eighth and early seventh centuries with the rivalry of Greek and Phoenician settlers in the West, and culminated with Alexanders capture of Tyre in the fourth century, Romes defeat of Carthage after the exhausting Punic wars of the third, and Carthages destruction in the second. Carthage had been the focus of Phoenician presence in the West for many hundred of years before it was leveled to the ground by the Romans in 146 BC. The Roman historian Appian gave a round figure of seven centuries for Carthages existence, which would imply a date for its founding about the middle of the ninth century. Timaeus, the Greek chronographer, gave the year 814 BC as the date of Carthages founding. Josephus dated Elissar's flight 155 years after the accession of Hiram, the ally of David and Solomon, that is, in 826 BC. Another tradition, associated with the fourth-century Sicilian chronographer Philistos, placed Carthages founding a mans life-length before the fall of Troy. Despite the fact that Philistos dating of the Trojan War is unknown, scholars have assumed that he put the date of the founding of Carthage in the thirteenth century.

Yet Appian, who followed Philistos in dating the founding of Carthage fifty years before the capture of Troy knew that the city had had a lifetime of not more than seven hundred years. Thus Appian dated the Trojan War to ca. 800 BC, and there is no reason to think that Philistos did not do likewise.

Archaeology, however, does not support a mid- or late-ninth century date for Carthages founding. After many years of digging archaeologists have succeeded to penetrate to the most ancient of Carthages buildings. P. Cintas, excavating a chapel dedicated to the goddess Tanit, found in the lowest levels a small rectangular structure with a foundation deposit of Greek orientalizing vases datable to the last quarter of the eighth century. These are still the earliest signs of human habitation at the site; although Cintas originally held out hope that there would be found remains of the earliest settlers of the end of the ninth century, the years have not substantiated such expectation. Scholars are now for the most part ready to admit that the ancient chronographers estimate of the date of the citys founding was exaggerated. But if Carthage was founded ca. 725 BC the Trojan War would, in the scheme of Philistos and Appian, need to be placed in the first quarter of the seventh century.

Sociopolitical Background

While Carthage was taking root as a city state, Tyre, its mother city, was under threat from the Assyrians. Its people migrated out in search of safety to various Phoenician colonies including new established Carthage. The beginning of the Carthaginian colony was the magnificent metropolis it evolved into. The citizens were merchants and made most of their money from the extraction of silver from mines in North Africa and southern Spain.

Their livelihood was in commerce but their experience from their original homeland positioned them to make something of themselves. However, Carthaginian ties to Tyre taxed and impoverished them from the relentless wars that were dealt against Tyre.

The Greeks took advantage of the situation and sent colonists into the Mediterranean, completely surrounding Carthage. In response, Carthage rounded up refugees from the fallen city of Tyre and other neighboring states to form a strong and united front against the Greeks.

By the middle of the 7th century BC Carthage had become the jewel of the Mediterranean. It was keeping the Greeks at bay and it had won several important battles that placed it in an authoritative position. Carthage began to set up trading posts that were soon turned into towns and cities to meet demand of the steady travel down the coast.

In the 6th century, the city became unquestionably a considerable capital with a domain divided into the three districts of Zeugitana (the environs of Carthage and the peninsula of C. Bon), Byzacium (the shore of the Syrtes), and the third comprising the emporia which stretch in the form of a crescent to the center of the Great Syrtis as far as Cyrenaica. The first contest against the Greeks arose from a boundary question between the settlements of Carthage and those of the Greeks of Cyrene. The limits were eventually fixed and marked by a monument known as the Altar of Philenae.

The destruction of Tyre by Nebuchadrezzar, in the first half of the 6th century, enabled Carthage to take its place as mistress of the Mediterranean. The Phoenician colonies founded by Tyre and Sidon in Sicily and Spain, threatened by the Greeks, sought help from Carthage, and from this period dates the Punic supremacy in the western Mediterranean. The Greek colonization of Sicily was checked, while Carthage established herself on all the Sicilian coast and the neighboring islands as far as the Balearic Islands and the coast of Spain. The inevitable conflict between Greece and Carthage broke out about 550 BC.

The Carthaginians made an alliance with the Persians (who had previously united Asia), to conquer the Greeks, yet it proved disastrously ill planned because it was a failure in 480 BC at Salamis and at Himera in Sicily. Carthage suffered as a result of this defeat.

Eventually, trade began to pick up and Carthage planned yet another attack on the Greeks in 409 BC. The Greeks were vulnerable following unsuccessful tries to conquer Sicily. The result was a hundred years of war between the Greeks and the Carthaginians and at different times, the destruction and annihilation of both powers seemed plausible.

In 332 BC Alexander conquered all of Phoenicia and humiliated Tyre and so there was no longer any hope of aid from Phoenicia. With Phoenicia, the main land too weak to help and pre-occupied with invasions, the western Mediterranean colonies looked to Carthage for aid and leadership. The defense of western Phoenician colonies fell to Carthage by default. Consequently, Carthage began to found her own colonies to better protect the livelihood of all Carthaginians. That causes more conflict with many people of the area especially the Greeks and later the Romans.

The reign of the famous Eastern World leader, Alexander the Great, between 334 and 323 BC, forced Carthage to change its political philosophy. It could no longer remain a private and aggressive colony or it would face the real possibility of economic ruin. So Carthage decided to accept the Hellenistic empire, especially the monarchy in Egypt, in order to have allies against Alexander.

Typically, the Hellenistic Age began with the death of Alexander the Great (323 BC) and ended with the conquest of Egypt by Rome in 30 BC. Hellenism was a fusion of Mediterranean religions, a cultural unity which was not broken until Muslim imperialism many years later.

During the reign of Alexander, Carthage had remained a Western stronghold, but this was soon to change with the threat imposed by Rome. Rome had traditionally stayed out of the way as far as Carthage was concerned because Rome was historically a farming colony, but in the second half of the fourth century and first of third, Rome had made several territorial conquests, and it pushed the limits by entering into Sicily at a time when Carthage was gaining control of the area. This invasion launched the first of the Punic Wars (263-241 BC), which ended in victory for Rome.

Hamilcar Barca led Carthage out of the depths of disaster by recapturing the mineral wealth of the west. Hamilcar created a military empire in Spain and announced himself absolute ruler (228-219 BC) After Hamilcar's death, Hasdrubal, his son in-law, and Hannibal, his son, conquered the entire Spanish peninsula up to the Ebro River.

Rome opened her eyes to the threat the great colony of Carthage poised. After a series of drawn-out battles, the Roman general Scipio conquered Spain in 210-206 BC. The last 50 years of existence of the colony were long and arduous. Carthage could have joined forces with Masinissa to become a united kingdom but was instead destroyed by Rome. When Carthage finally fell in 146 BC during the third and final Punic War, the area was scorched to the ground and all habitation in the former city was forbidden by the Romans because they considered it a rival city. Many Carthaginians were sold into slavery. The wife of the ruler of the city, rather than surrender, threw herself in to the flames of the Temple of Eshmun. She was probably a descendent of Elissar. However, the ban imposed on living in the city was lifted and later on Carthage returned to become an important one in the region.

What distinguished Carthage from its mother city, Tyre, was it marketing policies and diplomatic system. It did not remain a city state like Tyre but spread its dominion and authority on all Phoenician Punic colonies of the western Mediterranean. The Carthaginians created their own space and system even though they maintained good ties with their motherland until the Mediterranean became the Pond Nostrum of the Romans.

What was the city like?

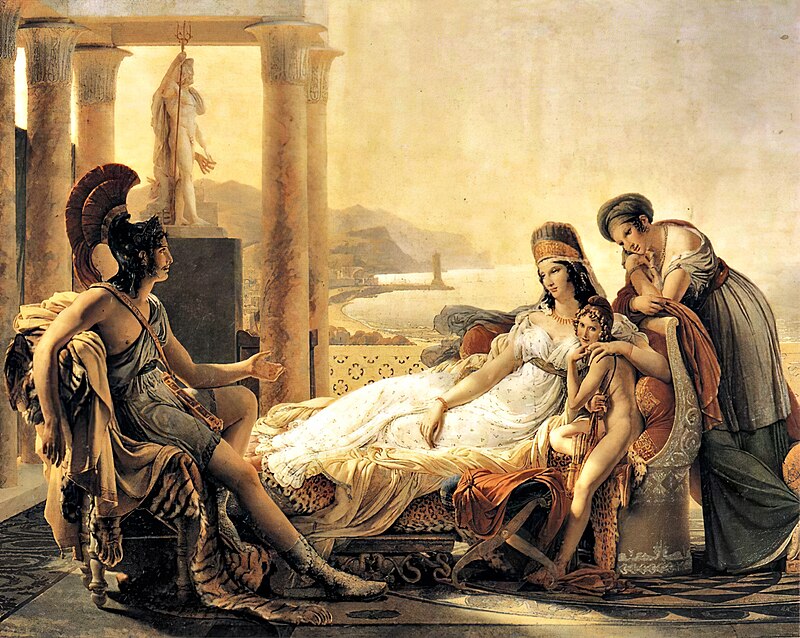

The city had two artificial harbors built inside the city walls, connected by a canal. The smaller one was a military harbor that held 220 warships. Further, it had a walled fortress, the Byrsa, overlooked the harbors, and was divided into four equal quarters with regular street plans. City walls were massive 23 miles and almost impregnable (compared to 5 miles for Rome). 3 miles of the walls along the isthmus were 40 feet high and 30 feet thick which were never breached. There were sacred area for cult sacrifices, a necropolis, market places, council house, temples, magnificent towers, city gates, a citadel, a theater, paved winding streets, gardens, and houses with great buildings up to six stories tall. It is said that when Aeneas visited Carthage, a harbor basin was being dug, and the foundations for a theatre had been laid. In its high-noon, the geographer Strabo calls it a "shining city," ruling 300 cities around the western Mediterranean.

The population of Carthage was about 700,000, an extraordinary number for cities in the ancient world, of merchants (who were in control of the city), as well as residents, explorers, landholding-agrarian faction and slaves. In the 6th to 5th century BC it began to dominate trade in western Mediterranean and brought great wealth. City defense was secured by a powerful navy backed by a mercenary army.

In the early 5th century BC, Carthaginian Hanno the Navigator sailed as far as the west coast of Senegal, and with that voyage began the tradition of tall tales about monsters and dangers west of Gibraltar.

Carthaginian Government

The emigrants to Carthage were civilized Tyrinians versed in culture, knowledge and law. They elected magistrates and established the Oligarchic Constitution with a governor who reported to the king of Tyre. They also elected parliament. Aristotle wrote ca. 340 B.C. in his "On the Constitution of Carthage" that it is to be held up as a model.

"The Carthaginians are also considered to have an excellent form of government, which differs from that of any other state in several respects, though it is in some very like the Spartan. Indeed, all three states---the Spartan, the Cretan, and the Carthaginian---nearly resemble one another, and are very different from any others. Many of the Carthaginian institutions are excellent. The superiority of their constitution is proved by the fact that the common people remain loyal to the constitution. The Carthaginians have never had any rebellion worth speaking of, and have never been under the rule of a tyrant. Among the points in which the Carthaginian constitution resembles the Spartan are the following: The common tables of the clubs answer to the Spartan phiditia, and their magistracy of the Hundred-Four to the Ephors; but, whereas the Ephors are any chance persons, the magistrates of the Carthaginians are elected according to merit---this is an improvement. They have also their kings and their Gerousia, or council of elders, who correspond to the kings and elders of Sparta. Their kings, unlike the Spartan, are not always of the same family, nor that an ordinary one, but if there is some distinguished family they are selected out of it and not appointed by seniority---this is far better. Such officers have great power, and therefore, if they are persons of little worth, do a great deal of harm, and they have already done harm at Sparta.

"Most of the defects or deviations from the perfect state, for which the Carthaginian constitution would be censured, apply equally to all the forms of government which we have mentioned. But of the deflections from aristocracy and constitutional government, some incline more to democracy and some to oligarchy. The kings and elders, if unanimous, may determine whether they will or will not bring a matter before the people, but when they are not unanimous, the people decide on such matters as well. And whatever the kings and elders bring before the people is not only heard but also determined by them, and any one who likes may oppose it; now this is not permitted in Sparta and Crete. That the magistrates of five who have under them many important matters should be co-opted, that they should choose the supreme council of One Hundred, and should hold office longer than other magistrates (for they are virtually rulers both before and after they hold office)---these are oligarchical features; their being without salary and not elected by lot, and any similar points, such as the practice of having all suits tried by the magistrates, and not some by one class of judges or jurors and some by another, as at Sparta, are characteristic of aristocracy.

"The Carthaginian constitution deviates from aristocracy and inclines to oligarchy, chiefly on a point where popular opinion is on their side. For men in general think that magistrates should be chosen not only for their merit, but for their wealth: a man, they say, who is poor cannot rule well---he has not the leisure. If, then, election of magistrates for their wealth be characteristic of oligarchy, and election for merit of aristocracy, there will be a third form under which the constitution of Carthage is comprehended; for the Carthaginians choose their magistrates, and particularly the highest of them---their kings and generals---with an eye both to merit and to wealth. But we must acknowledge that, in thus deviating from aristocracy, the legislator has committed an error. Nothing is more absolutely necessary than to provide that the highest class, not only when in office, but when out of office, should have leisure and not disgrace themselves in any way; and to this his attention should be first directed. Even if you must have regard to wealth, in order to secure leisure, yet it is surely a bad thing that the greatest offices, such as those of kings and generals, should be bought. The law which allows this abuse makes wealth of more account than virtue, and the whole state becomes avaricious.

"For, whenever the chiefs of the state deem anything honorable, the other citizens are sure to follow their example; and, where virtue has not the first place, their aristocracy cannot be firmly established. Those who have been at the expense of purchasing their places will be in the habit of repaying themselves; and it is absurd to suppose that a poor and honest man will be wanting to make gains, and that a lower stamp of man who has incurred a great expense will not. Wherefore they should rule who are able to rule best. And even if the legislator does not care to protect the good from poverty, he should at any rate secure leisure for them when in office. It would seem also to be a bad principle that the same person should hold many offices, which is a favorite practice among the Carthaginians, for one business is better done by one man.

Christian Church Synods anc Councils of Carthage,

Carthage enjoys prosperity and becomes a center of the Christian church in the West

During the 3rd, 4th, and 5th centuries the city of Carthage served as the meeting-place of a large number of church synods and councils to deal with ecclesiastic matters.

1. In May 251 a synod, assembled under the presidency of Cyprian to consider the treatment of the lapsi (those who had fallen away from the faith during persecution), excommunicated Felicissimus and five other Novatian bishops (Rigorists), and declared that the lapsi should be dealt with, not with indiscriminate severity, but according to the degree of individual guilt. These decisions were confirmed by a synod of Rome in the autumn of the same year. Other Carthaginian synods concerning the lapsi were held in 252 and 254.

2. Two synods, in 255 and 256, held under Cyprian, pronounced against the validity of heretical baptism, thus taking direct issue with Stephen, bishop of Rome, who promptly repudiated them, and separated himself from the Church in north Africa. A third synod, September 256, unanimously reaffirmed the position of the other two. Stephens pretensions to authority as bishop of bishops were sharply resented, and for some time the relations of the Roman and Churches in north Africa were severely strained.

3. The Donatist schism occasioned a number of important synods. About 348 a synod of Catholic bishops, who had met to record their gratitude for the effective official repression of the Circumcelliones (Donatist terrorists), declared against the rebaptism of any one who had been baptized in the name of the Trinity, and adopted twelve canons of clerical discipline.

4. The Conference of Carthage held by imperial command in 411 with a view to terminating the Donatist schism, while not strictly a synod, was nevertheless one of the most important assemblies in the history of the church in Africa, and, indeed of the whole Christian church.

5. On the 1st of May 418 a great synod, which assembled under the presidency of Aurelius, bishop of Carthage, to take action concerning the errors of Caelestius, a disciple of Peagius, denounced the Pelagian doctrines of human nature, original sin; grace and perfectibility, and fully approved the contrary views of Augustine. Prompted by the reinstatement by the bishop of Rome of a deposed Carthaginian priest, the synod enacted that whoever appeals to a court on the other side of the sea (meaning Rome) may not again be received into communion by any one in the church in Africa (canon 17).

6. The question of appeals to Rome occasioned two synods, one in 419, the other in 424. The latter addressed a letter to the, bishop of Rome, Celestine, protesting against his claim to appellate jurisdiction, and urgently requesting the immediate recall of his legate, and advising him to send no more judges to Africa.

References

References may be found on the article's source page.

**********

Good riddance; the baby killing Baal worshippers deserved to be annihilated.

Good riddance; the baby killing Baal worshippers deserved to be annihilated.