Emphasis is the article's.

---

http://ftalphaville.ft.com/2014/09/23/1980232/india-a-finite-balance/

India: A finite balance

David Keohane

For those who don’t know, India is a big, extremely uneven, place. From HSBC (with our emphasis):

India is a federation, with the central and state governments having both separate and shared responsibilities. While central government policies and transfers shape state policy agendas, states still have a relatively high degree of autonomy. As a result, state policies vary greatly.

The rise of India can be seen in each state, but in some more than others. Between the 1990s and 2000s a handful saw average growth rates jump significantly – Uttarakhand in the north (8.5ppts) and Bihar (5.1ppts), Sikkim (8.4ppts) and Nagaland (4.7ppts) in the east.

A number of states and union territories have averaged double-digit growth since 2000, including Uttarakhand, Chandigarh, Sikkim and Nagaland. However, these are all relatively small states. The larger economies that have delivered impressive growth rates in this period include New Delhi (8.6%), Haryana (8.6%), Gujarat (8.8%), Maharashtra (7.7%) and Bihar (8.5%).

Volatility in the rate of growth also differs. Some states are more susceptible to changes in global economic conditions and subsequently took a relatively large hit during the global financial crisis of 2008-09. They were typically states with a larger share of manufacturing (Gujarat and Maharashtra) and a sizeable business services sector (Gujarat and Maharashtra again, and also Karnataka, which has a relatively large IT services sector).

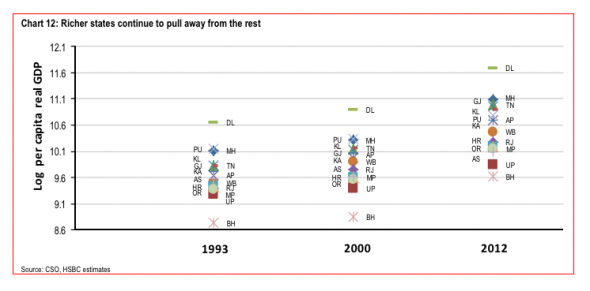

And what about relative performance – is the gap between states closing? The answer is no. The richer states have, on average, experienced relatively faster per capita GDP growth than the poorer states, despite the strong performance of low income states such as Bihar, Orissa and Uttarakhand. The reality is that the pace at which richer states are pulling away appears to be increasing.

And in chart form:

This is connected to the (unanswerable?)

Sen – Bhagwati debate about the nature of India’s growth, the particularities of societal rigidity and caste politics and the questionable reality of trickle-down effects in a country which is overtly unequal — both within and between cities and states. But rather than get into that, there are some obviously simplistic policy implications here:

The quantitative analysis shows that initial conditions, such as the combination of income per capita and high growth, matter for the growth performance in subsequent decades. Demographics, on the other hand, do not appear to explain cross-state differences in growth performance. This is consistent with our previous finding that the demographic dividend may not yet be fully exploited, as growth in states with fast-growing populations faces a number of structural growth constraints.

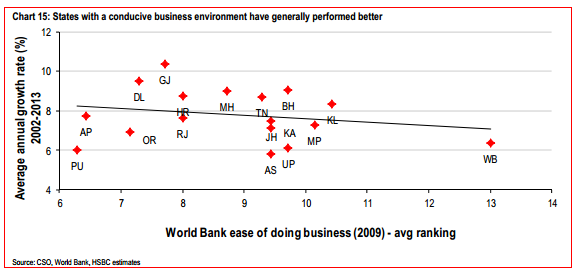

However, the degree of business friendliness matters greatly for the relative growth performance of individual states. In our model, we have measured the degree of business friendliness as a composite measure, calculated as the product of: 1) the World Bank ranking for getting construction permits; 2) the World Bank ranking for trade openness; and 3) the OECD score for entrepreneurial product market rigidity.

According to the model estimates, a hypothetical state ranking at the top of the league in terms of business friendliness, as per our composite measure, will have a growth advantage of more than 4ppts over a state with the poorest business environment.

In reality, however, the most business friendly states do not get top grades across all categories and the least business friendly states do not consistently get bottom grades either. This means that differences in business friendliness in India are smaller than in the hypothetical case.

In reality, therefore, actual differences in business friendliness explain less than 4ppts between the best and worst states in terms of growth; however, it can still explain a large chunk of the relative growth performance over the past decade.

Extremely relevant when discussing

Modi’s slow-burn reforms even it leaves the broader social questions largely unanswered. More, including the maps below, in

the usual place.

And the companion piece:

http://blogs.ft.com/beyond-brics/2014/09/23/forget-modi-indias-states-hold-the-key/

Forget Modi, India’s states hold the key

Sep 23, 2014 2:00pm

by Mian Ridge

Investors interested in India are watching Prime Minister

Narendra Modi to see if he will deliver the reforms needed to kick-start the economy.

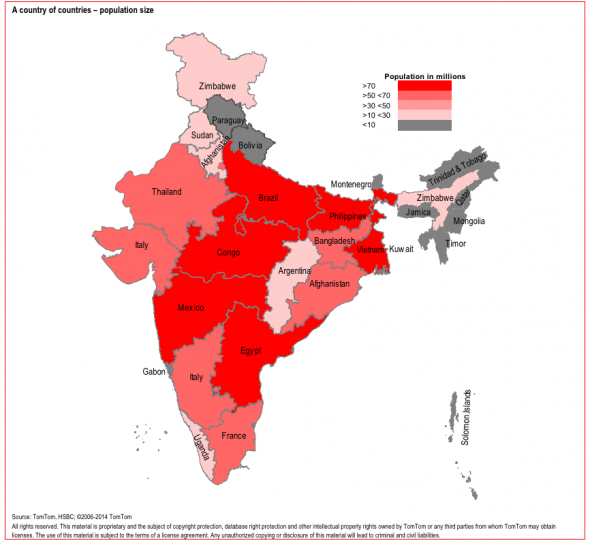

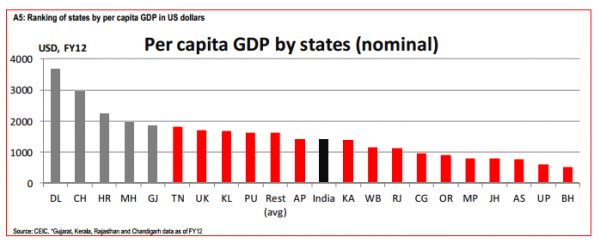

But India’s economic future is also being determined to a large degree at the state level, according to HSBC, with some states surging forward and others lagging behind. The per capita GDP of Delhi, for instance, is $3,600. In the vast state of Uttar Pradesh, which has a population roughly the size of Brazil’s, it is $690.

That puts Delhi on a par with Ukraine, and Uttar Pradesh with Rwanda.

Better infrastructure, a larger private sector and – crucially – friendlier business environments seem to be the ingredients for a successful state, it said

in a note:

Unfolding the tapestry – a guide to India’s states.

India is too often looked at as “one homogenous country”, but there are important differences across India’s 36 states and territories. The rise of local political parties in recent years has given states more independence, and fiscal autonomy has increased too, with obvious results:

For example, some are opening up their economies, cutting red tape and introducing reforms based on what works for them. In turn, this has delivered impressive growth rates. Others are not making much progress in these areas and are struggling to deal with significant poverty. A top-down, one-size-fits-all perspective does not work for a country as vast and diverse as India.

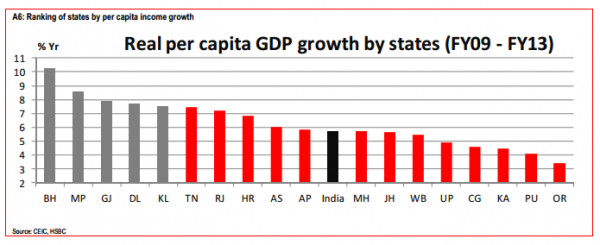

The picture is indeed complex. Bihar, which has one of the highest levels of poverty in India and a pitiful per capita GDP of $529, also happens to be one of a handful of dynamic states that have delivered impressive growth rates since 2009 (see chart) thanks in its case to state-level reforms.

Others include Gujarat, where Modi was chief minister for over a decade, and the central state of Madhya Pradesh which benefits from its proximity to Delhi.

This is also reflected in per capita GDP numbers (see chart).

HSBC observes that much has been made of India’s “demographic dividend”: 50 per cent of Indians are aged under 24, compared to 36 per cent in China and 42 per cent in Brazil.

The dividend can remain unpaid, it shows. The states with faster growing workforces were not been the growth leaders in the 2000s, because other constrains on growth – lack of infrastructure, skills gaps and restrictive labour and product markets – had held them back.

Our quantitative analysis shows that what matters most for economic growth is a combination of the underlying conditions (for example, how rich or poor the state is) and how easy it is to do business.

Five states accounted for half of total investments in 2011. Three of them – Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh, and Orissa – were also ranked as the most business friendly states in a 2009 World Bank survey.

Our quantitative analysis shows that the relative differences in business friendliness can explain up to 2.5 ppts of the growth differential between the reformist and non-reformist states.

There were reminders throughout the note that the task of unshackling India from the tightly controlled “Licence Raj” begun by Manmohan Singh when he was finance minister in the 1990s, remained but “half done”.

Despite a handful of industrialised states, India has a low industrial base, and that was down to poor infrastructure and rigid labour markets.

The combination of the strict rules about laying off workers, which do not apply to service companies, and the reservation of specific areas for small operations, have restricted the scale of businesses. Almost 90% of manufacturing employment involves enterprises with fewer than 10 employees. This has effectively prevented many Indian states from exploiting economies of scale, with major implications for growth.

Meanwhile the dominant economic sector, services, which HSBC expected to grow, faced competition from other countries.

This means that India, at both the central and state level, has to work hard to retain its competitive edge on these fronts by pushing through reforms to raise skill levels and aligning skills with future private sector needs. India should, however, also enable growth in other segments of the services sector, for example, by further opening up the retail sector to foreign companies.