A well written article. A fine tribute to a soldier.

A trifle old but then its the Military History forum.

Ahmadiyya Times: Forgotten Heroes: Lt. Gen Abdul Ali Malik - "The Ali of Chawinda"

It is said that old soldiers never die. They just fade away; and one did just the other day. He faded away slowly and gently, without a whine or whimper or even a sigh of reproach. He slid way gracefully as was his wont to do everything in life.

And then as if jolted back to reality by the serenity that ended with him, they took his mortal remains to the dusty little village that had given him birth as gift to the nation. There he was returned to its earth beside a clump of stunted trees while his villagers, a few peers, half a dozen generals and a contingent of his parental regiment looked on. There were no tears or wailing. And if there was grief, it was well submerged in pride.

It was military function and this was a martial village. And yet again the army played its part with style. A smartly turned-out detachment of 19 Punjab Regiment presented arms and then fired its farewell salvo and a bugler played the “last post”. And only then, as the last notes floated away did moisture force its way into the eyes. And as they glistened in the sun making ready to take leave, a thousand memories came alive in a flash.

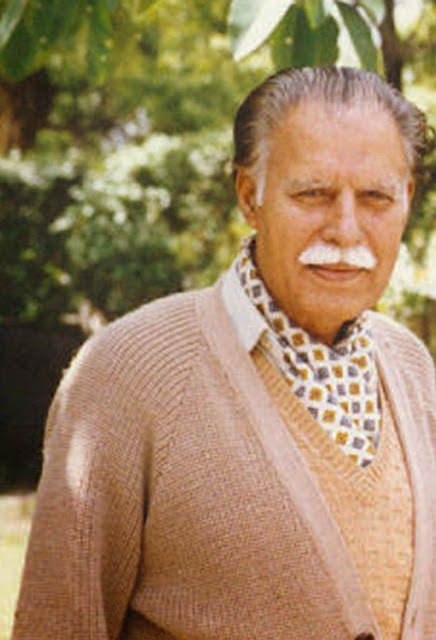

This man who had just been lowered under the shade in Pindori village was a hero of the nation – an unsung one – but then in a nation of false heroes, it should surprise few that Lt General Abdul Ali Malik should have walked into dusk relatively unnoticed.

He was a tall, unassuming man, who, one would have thought, was not the stuff to occupy any lofty perch in history books. Soft spoken, gentle in manner, and graceful in conduct, he seemed destined to live out his life, being best remembered as the younger brother of the great General Akhtar Malik – the flamboyant, charismatic, and brilliant solider who seemed to have destiny at his command.

But fate has peculiar scripts to play to. And no other script could have been more poetic in its justice than the one unravelled in 1965. General Akhtar Malik conceived, planned, and launched ‘Operation Gibraltar’. When this was complemented by ‘Grand Slam’, the stage was set for men to make their mark on history.

That it was our misfortune to have men in command over our destiny who were better suited for service as guardians in Turkish harems, is a fact only we as a nation could ignore. And ignore we did with such brazen flair for falsehood that we painted victory in debacle and made heroes of conniving blackguards. This laid the foundation of a leadership that would march us off to ignominy in 1971.

But in 1965 the Pakistan Army, thirsty for glory and aroused by the dare and imagination of one man, stood poised for a while on the confines of a historic victory. The dramatic dash to Tawl, the very real probability of the fall of Akhnur, the vision of a final sweep to Jummu and the ensuing results to be only contemplated, was heady stuff indeed. But then mediocrity and sheer lack of nerve, coupled with selfish political motives, base enough to take the place of treason, denied our armed forces the fruit of their gallantry.

General Akhtar Malik, a winning general, was removed from command in mid-battle, and replaced by Yahya. And while he dawdled, the Indians struck at Pakistan - first at Lahore and then at Chawinda.

There was a solitary infantry brigade at Chawinda, bolstered by an armoured regiment. The man in charge was

Brigadier Abdul Ali Malik. The time to test his mettle had arrived. And with what fine irony it did so.

Whereas the elder brother had been removed from command to deny him the glory that was his due, it fell on the shoulders of the younger brother to contain the fallout of this disastrous decision and stem the rot. With the change of command in the Chamb Sector any chance of a Pakistan victory had been strangulated. The initiative was passed on to the enemy, and India lost little time in going for our jugular. This was Chawinda. Break through 24 Brigade and sit astride the GT Road at Gujranwalla, and that would be the end of the story for Pakistan.

A frantic message went out to Brig Malik. At Chawinda he left 3 FF, a company of 2 Punjab, a platoon of R & S and some artillery. With the rest of the brigade he moved to contain the Indians at Jassar.

There were no Indians there to contain. But there were some coming down Charwa-Chawinda track –- a whole four divisions of them. And leading the advance with due arrogance was their famed ‘Elephant’ division – the armoured division of the Indian Army, their pride and strike force. Preceded by a formidable artillery barrage, the Indians overran a badly outnumbered 3FF. The company of 2 Punjab found itself fortuitously placed at the flank of the advancing enemy. It prudently withdrew southwards in good order. The R & S platoon made its plan according to its own lights and ran accordingly.

Brig Malik was oblivious of this till a thoroughly shaken engineer havildar blundered into 2 Punjab Regiment headquarters and told Lt Col Jamshed, the commanding officer, that the Indians had attacked and taken all our positions ahead of Chawinda. He could not say how strong the Indian force was, except that they had tanks.

This information was conveyed to Brig Malik, and he, without referring to the divisional headquarters,

took the first of his three crucial decisions of the war. He ordered his staff officer to break communications with the higher headquarters, lest they sow any more confusion in the already confused state of affairs, and ordered the brigade straight to Chawinda. With little more to go on than the word of one runaway NCO, he had to take a decision. He knew the enemy order of battle across his sector. He knew also that the main Indian effort will fall somewhere in the Sialkot sector. He had been to Jassar and knew what it was. He thus decided that Chawinda had to be it. And he ordered the move on his own.

He was among the first to arrive at Chawinda just as dawn was breaking through the night.

He saw the stream of withdrawing troops raise clouds of dust, sowing demoralisation with each step they took. There was panic in the air, rapidly giving way to a sense of doom.

The Brigadier, with Colonel Jamshed next to him, surveyed the scene of his disintegrating command from a hillock. His calm and poise, as he did so, were almost unreal.

I was present there to report to my Commanding Officer. I was at Charwah, and a part of my company had been overrun by a squadron of tanks that morning.

“What kind of tanks”? asked Lt Col Nisar Commanding Officer 25 Cavalry, who had just joined us.

“Small ones Sir”, I said. I was too busy dodging them to notice what type they were.

“How far”?

“A mile Sir, may be more”.

And then the Brigadier spoke, decisively, firmly “Stop those men and put them in defence there”, he pointed to an area just west of Chawinda. And then to Nisar: “how many tanks do you have?

“One squadron Sir, right here, another is dismounting from the transports nearby.”

And then Brigadier Abdul Ali Malik took

his second, the most extraordinary, the most audacious decision of this, or any war. He could have been prudent, careful and conventional. No one would have blamed him if he had put all available troops in defensive positions around Chawinda. Indeed none would have even grudged him a limited withdrawl. But he did not do this. He ordered Nisar to put his two squadron in extended line and go over to the offensive, 2 Punjab he was informed, would join him as soon as it reached there. And to his everlasting credit Lt Col Nisar said “Yes Sir” and hurried away – no hesitation, no delay, and no arguments. It was just “Yes Sir”.

And for the first time in the history of tank warfare two squadrons were about to take on an armoured division. This momentous decision, not recommended in any text book, was to save Pakistan from total defeat.

And as they moved out the officers and men of 25 Cavalry epitomised the gallantry and spirit that pervaded the army and the nation in 1965. They were brash and confident –an incarnation of mythical qualities bequeathed to them by generations of conquerors. The 2 Punjab Company following the tanks was commanded by Major Muhammad Hussain Malik. I was attached to him. He was hard of hearing and his handicap was not slight. He thus had the great advantage of not being able to fully register the hell that the Indian guns were plowing up . Whenever a shell landed nearby someone had to point out the crater to him, to have him register what was really going on. Short of that he resented men taking cover for no apparent reason. While he strode manfully along, advancing towards the enemy. It was an incredible advance. Maj Malik would not bear being left behind the tanks. So we had to be on the double. The sound of tank fire spurred us on. Soon we saw the first Indian casualties. They were tanks – centurions which our magnificent cavalry had knocked out.

We advanced all day in short bursts, from cover to cover. The Indians were retreating by the afternoon. We reoccupied Phillaurah, then Godgore, then Chobara. And Maj Malik asked, half in jest, if the Brigadier would have us take Delhi the same day. But then it was dusk, and the tanks withdrew to leaguer for the night. We were overextended and so had to abandon Chobara and take up defence around Godgore. As night fell we were very tired and utterly triumphant. Two squadrons of tanks and one infantry company had blunted and then beaten back what was one armoured division and three of infantry! The sheer momentum of such a massive Indian force should have allowed them to do better. But then who could have predicted that an infantry Brigadier would react in quite the manner that Brigadier Ali had done under the circumstances?

The next morning we discovered a marked map in an abandoned Indian jeep. This showed their entire order of battle. Only then we realized what we were up against. This was the 1st Indian Armoured Division, 6th 26th infantry division and 14th infantry division. We were stunned by our achievements of the previous day, and also made urgently conscious of how pitifully thin we were not the ground.

Brigadier Ali drove up to us on the 9th morning. He had seen the map. His hunch had been confirmed, but many in GHQ still doubted if in fact we were really up against the real thing, or whether it was a feint. We needed to be reinforced, and that too, urgently.

The Brigadier stood discussing the situation with Lt Colonels Jamshed and Nisar. I was there too. We were interrupted by a salvo that fell short of us, and then another that went plus – some Indian observation post was obviously ranging in on us. And then came the third salvo. We knew this would be the real one. We went to the ground. In this interval between going down and getting up, the Brigadier seemed to have made up his mind. Our defence would not be able to hold an Indian attack; no reinforcements could be expected; withdrawal was out of the question; so there was only one option left – to attack. Incredible? Yes, but true – we were again ordered to attack.

I hauled myself on a roof- top to see ahead; just beyond, the whole plain was dotted with Indian tanks, trucks and jeep etc. We asked for instructions. They were short crisp as the Brigadiers always were --- “stay there”.

We had come out of a great fight with honour. It was just four days of battle but the results were incredible and miraculous if not mythical. And no one deserved more credit for this than did Brigadier Ali. Whether by sheer inspiration or by calculation, or a bit of both, he had wrought a miracle. The men under is command were no better than the others in the army. True, he had four excellent Lt Colonels under his command, but other commands too had such officers. The truth is that in this battle Brigadier Abdul Ali Malik alone was worth a whole armoured division by himself. He was the ace of trumps in this deck. Him alone.

But his day was not yet done. On the 11nth Indians broke through the position that we had taken back from them and routed our replacement. Frantic messages came to Brigadier Ali to get back and stop the enemy. And Ali went again.

We reached Chawinda at dusk. The signs of defeat were all over—stragglers moving back, some without weapons, some without their helmets and web equipment, without a semeblance of discipline or any sign of cohesion – demoralised troops, defeated. And all this in less than 24 hours! It was an amazing transformation of a battle scene that we had left only a short time ago.

We dug in around Chawinda. Brigadier Ali had his headquarters in the village itself. He was determined that he would defend the village no matter what.

This was his third crucial decision of the war and as critical to the survival of Pakistan as the earlier two. Perhaps he assessed that by this time the Indians had come to know exactly what stood against them. There was now no room left for bluff. Now there would be a dour merciless battle to the end.

They threw everything at us. They often came close to success. Many times it seemed that our defence had disintegrated, only to be rallied round again. But we stood our ground because one man has decided that he was not going to be moved. There was a strange transformation about this man. The cavalier in him had given way to the stoic. He was still as calm and as composed as ever---- four Indian divisions were not quite enough to ruffle his poise. The only real change in demeanor was that he smiled less often, and his jaw seemed more firmly set. He knew that if Chawinda fell, all will fall with it. So he will stand his ground. They were going to thrash him but they were not going to beat him.

He was so averse to the word ‘withdrawal’ that once when his Headquarters became a recognized target of the enemy artillery, and he was forced to abandon it for a different location, instead of moving it to the rear, he planted it right in the front lines barely 100 yards from the forward trenches of my battalion.

His presence among us was an inspiration for the troops. There he made plain that we would fight to the last man. “Oh my God”, I thought to myself, “the Old Man is really determined to stake himself out like an Indian chief!” The thought, I must confess, was not the most inviting one. But when a commander leads by example, everything becomes acceptable.

In the end it did not come to that. Ali’s dogged determination broke the will of the enemy. We held on to Chawinda till the guns fell silent. And almost immediately people started to steal credit from the colossus who was too selfeffacing to talk about himself. He preferred instead to fade away.

But one final moment of glory yet remained for him.

It came when the Field Marshal descended upon Pasrur airfield where the officers of all the formations were summoned after the war, so that he could address them. He had been told that there was widespread discontent with the way the war was conducted, by the senior officers.

The generals in charge were being ridiculed, not only by the junior officers, but often by the rank and file too. We had held our own against the Indians in spite of the generals, it was being openly said. Ayub Khan, in his address, said that he had heard about this talk but he could not understand why such sentiments were being expressed. He then referred to the battle at Chawinda.

“Look what happened here at Chawinda”, he said. “The Indians attacked but Ali was there.”

Ali was there. That was all that mattered. Because Ali was there, the generals were absolved. Yes, he was there alright. And let this nation be thankful that he was, even now when he no longer is.”