F-22Raptor

ELITE MEMBER

- Joined

- Jun 19, 2014

- Messages

- 16,980

- Reaction score

- 3

- Country

- Location

The United States and China are the world’s two most important economic powers. But they face polar opposite economic problems.

The United States has struggled with rising consumer prices over the past 18 months, with inflation still considerably ahead of the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent target despite attempts to slow down spending and 3.2 percent year on year last month, according to data released Thursday.

China faces a different problem: Deflation. According to official statistics released Wednesday, consumer prices had fallen by 0.3 percent over the last year after being stagnant for months.

And while America has a startlingly tight labor market, with more job openings than out-of-work people, China is facing enormous unemployment problems. The unemployment rate for 16- to 24-year-olds hit a record 21 percent in June — though some experts believe it is actually even higher.

There is one significant similarity, though it doesn’t look good for Beijing. While China has a 5 percent official target for economic growth this year, that growth is year on year with 2022, a year when economic activity was severely limited by “zero covid” rules. Economists from Bloomberg News have said growth would look more like 3 percent under normal circumstances — not so far above the 2.5 percent that JPMorgan now predicts for the United States.

That slower rate would be well off-track for a country that was, pre-pandemic, a driver of global economic growth. And there are more worrying signs for China too, including declining international trade, spiraling government debt and domestic property investment.

On a global level, it is China that is the outlier rather than the United States. The inflation and job market woes seen in the United States are echoed across almost all major economies. Economists attribute this to government stimulus packages and structural unemployment during the pandemic, as well as increased spending after covid-19 subsided.

In the United States and elsewhere, this presents an immediate political problem. While President Biden has claimed that his “Bidenomics” is creating a “soft landing” by bringing down inflation without causing a spike in unemployment, polls show that ahead of the election many Americans are still feeling the pinch of higher prices and fear a recession.

The problems in China’s economy may also be a result of covid-19, but they are distinct — and perhaps more drastic. The country’s stringent response to the pandemic — the “zero covid” policy that implemented mass lockdowns, testing, quarantine and border control — may have saved far more lives than the less organized efforts in the United States and elsewhere, but it ended abruptly and chaotically, negating many of its successes.

It may have left a far worse economic hangover. Writing in Foreign Affairs earlier this month, U.S. economic policy expert Adam Posen argued that what we are seeing now represented the “end of China’s economic miracle,” linking the strict covid-19 rules to a growing economic anxiety that causes people to hoard their money, despite low-interest rates, leading to deflation.

Economists have also tracked a huge decrease in foreign direct investment in China, likely both a result of covid-19 restrictions and economic gloom in the country but also the trade war initiated by the Trump administration against Beijing.

How bad could things get? One common point of comparison is Japan, another once-rising Asian economic power that caused major anxiety in Washington and Europe. Booming in the 1970s and 1980s, its bubble burst in the 1990s and the country entered decades of economic stagnation and deflation that effectively made its citizens poorer and its national debt more burdensome.

But China of 2023 is not the Japan of 30 years ago. China has a population of 1.4 billion, more than 10 times the size of Japan even now. When adjusted for purchasing power, its economy has been bigger than the United States since 2015. Japan’s was never more than half the United States’.

Moreover, Japan is a functioning, if imperfect, democracy. China is an autocracy that has become only more closed off over recent years. Even getting economic data is becoming more difficult, with the word “deflation” taboo in official language and an anti-espionage law making officials cautious of speaking to outside experts, even privately.

“You’ve got an economic slowdown that would worry any country, coupled with a China that always likes to put on a brave face to the world and a leadership that is particularly image-conscious,” Andrew Collier, managing director of Orient Capital Research in Hong Kong, toldthe Financial Times. “Put those three factors together and it’s the recipe for a very non-transparent economy.”

At the same time, there are persistent fears about China’s foreign policy intentions — President Xi Jinping has hinted at major action against the self-governing island of Taiwan, risking a global war that could drag the United States and others in. Just this week, The Washington Post broke the story of how China had infiltrated Japan’s defense networks.

Japan’s economic fall to earth was a peaceful affair. In a New York Times column last month, economist Paul Krugman argued that the country had actually handled its key economic problem — a demographic shift from a young to an elderly society — relatively well. China, another aging society, faces a similar problem. It may not handle it anywhere near as well.

“So, no, China isn’t likely to be the next Japan, economically speaking,” Krugman wrote. “It’s probably going to be worse.”

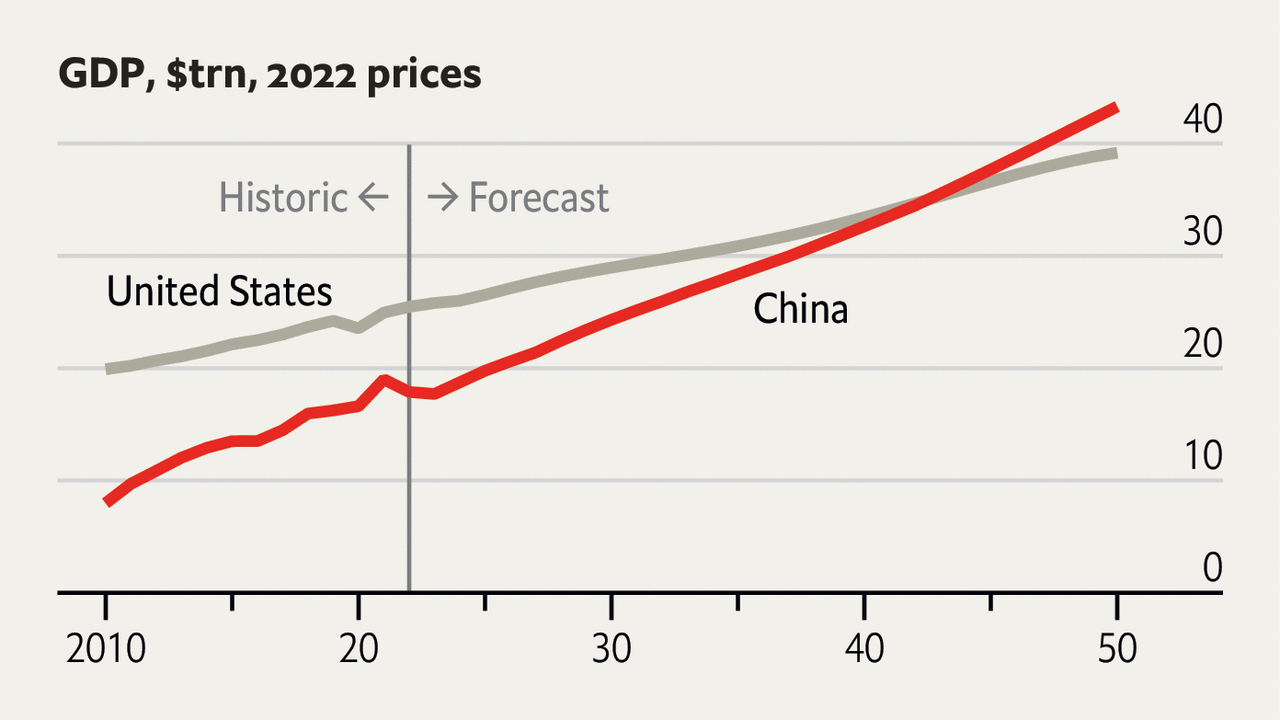

For the rest of the world, that makes China’s economy one to watch closely. Any turmoil in the country could spark unexpected consequences elsewhere in the world, both economically and politically. As Posen writes, for the United States it could well be an opportunity to put this economic rivalry to bed. At the least, China’s dreams of economically eclipsing the United States may be forever delayed.

The United States has struggled with rising consumer prices over the past 18 months, with inflation still considerably ahead of the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent target despite attempts to slow down spending and 3.2 percent year on year last month, according to data released Thursday.

China faces a different problem: Deflation. According to official statistics released Wednesday, consumer prices had fallen by 0.3 percent over the last year after being stagnant for months.

And while America has a startlingly tight labor market, with more job openings than out-of-work people, China is facing enormous unemployment problems. The unemployment rate for 16- to 24-year-olds hit a record 21 percent in June — though some experts believe it is actually even higher.

There is one significant similarity, though it doesn’t look good for Beijing. While China has a 5 percent official target for economic growth this year, that growth is year on year with 2022, a year when economic activity was severely limited by “zero covid” rules. Economists from Bloomberg News have said growth would look more like 3 percent under normal circumstances — not so far above the 2.5 percent that JPMorgan now predicts for the United States.

That slower rate would be well off-track for a country that was, pre-pandemic, a driver of global economic growth. And there are more worrying signs for China too, including declining international trade, spiraling government debt and domestic property investment.

On a global level, it is China that is the outlier rather than the United States. The inflation and job market woes seen in the United States are echoed across almost all major economies. Economists attribute this to government stimulus packages and structural unemployment during the pandemic, as well as increased spending after covid-19 subsided.

In the United States and elsewhere, this presents an immediate political problem. While President Biden has claimed that his “Bidenomics” is creating a “soft landing” by bringing down inflation without causing a spike in unemployment, polls show that ahead of the election many Americans are still feeling the pinch of higher prices and fear a recession.

The problems in China’s economy may also be a result of covid-19, but they are distinct — and perhaps more drastic. The country’s stringent response to the pandemic — the “zero covid” policy that implemented mass lockdowns, testing, quarantine and border control — may have saved far more lives than the less organized efforts in the United States and elsewhere, but it ended abruptly and chaotically, negating many of its successes.

It may have left a far worse economic hangover. Writing in Foreign Affairs earlier this month, U.S. economic policy expert Adam Posen argued that what we are seeing now represented the “end of China’s economic miracle,” linking the strict covid-19 rules to a growing economic anxiety that causes people to hoard their money, despite low-interest rates, leading to deflation.

Economists have also tracked a huge decrease in foreign direct investment in China, likely both a result of covid-19 restrictions and economic gloom in the country but also the trade war initiated by the Trump administration against Beijing.

How bad could things get? One common point of comparison is Japan, another once-rising Asian economic power that caused major anxiety in Washington and Europe. Booming in the 1970s and 1980s, its bubble burst in the 1990s and the country entered decades of economic stagnation and deflation that effectively made its citizens poorer and its national debt more burdensome.

But China of 2023 is not the Japan of 30 years ago. China has a population of 1.4 billion, more than 10 times the size of Japan even now. When adjusted for purchasing power, its economy has been bigger than the United States since 2015. Japan’s was never more than half the United States’.

Moreover, Japan is a functioning, if imperfect, democracy. China is an autocracy that has become only more closed off over recent years. Even getting economic data is becoming more difficult, with the word “deflation” taboo in official language and an anti-espionage law making officials cautious of speaking to outside experts, even privately.

“You’ve got an economic slowdown that would worry any country, coupled with a China that always likes to put on a brave face to the world and a leadership that is particularly image-conscious,” Andrew Collier, managing director of Orient Capital Research in Hong Kong, toldthe Financial Times. “Put those three factors together and it’s the recipe for a very non-transparent economy.”

At the same time, there are persistent fears about China’s foreign policy intentions — President Xi Jinping has hinted at major action against the self-governing island of Taiwan, risking a global war that could drag the United States and others in. Just this week, The Washington Post broke the story of how China had infiltrated Japan’s defense networks.

Japan’s economic fall to earth was a peaceful affair. In a New York Times column last month, economist Paul Krugman argued that the country had actually handled its key economic problem — a demographic shift from a young to an elderly society — relatively well. China, another aging society, faces a similar problem. It may not handle it anywhere near as well.

“So, no, China isn’t likely to be the next Japan, economically speaking,” Krugman wrote. “It’s probably going to be worse.”

For the rest of the world, that makes China’s economy one to watch closely. Any turmoil in the country could spark unexpected consequences elsewhere in the world, both economically and politically. As Posen writes, for the United States it could well be an opportunity to put this economic rivalry to bed. At the least, China’s dreams of economically eclipsing the United States may be forever delayed.