beijingwalker

ELITE MEMBER

- Joined

- Nov 4, 2011

- Messages

- 65,191

- Reaction score

- -55

- Country

- Location

Why hasn’t U.S. poverty improved in 50 years? Pulitzer-prize winning author Matthew Desmond has an answer

Annie Nova@ANNIEREPORTERPUBLISHED THU, MAR 23 20239:00 AM EDT

KEY POINTS

- In his new book, “Poverty, by America,” Matthew Desmond says that poverty persists in the U.S. because many Americans and large companies profit from it.

- “I want to be clear: I’m not calling for redistribution,” Desmond said. “What I’m talking about is less rich aid and more poor aid.”

- The author also has tips on how people can become “poverty abolitionists.”

Why US hasn't solved poverty

Over the last 50 years, Americans have eradicated smallpox, reduced infant mortality rates and deaths from heart disease by around 70%, added a decade to the average American’s life and invented the internet.

When it comes to the national poverty rate, however, we’ve made almost no progress. In 1970, a little more than 12% of the U.S. population was considered poor. By 2019, around 11% was.

In his new book, “Poverty, by America,” sociologist Matthew Desmond proposes a reason for that stagnation: We benefit from it.

I spoke with Desmond this month about his argument that many individuals and large U.S. companies profit from tens of millions of Americans living in poverty, and how things might finally start changing.

His last book, “Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City,” won the 2017 Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction. (Our interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.)

Annie Nova: Your book starts with a quote by Tolstoy: “We imagine that their sufferings are one thing, and our life another.” How are we able to be so detached from the state in which so many others are living?

Matthew Desmond: The country is so segregated. I think many of us can go about our daily lives only confronting poverty from the car window or in the news.

AN: Many financially comfortable and well-off Americans, you write, live as “unwitting enemies of the poor.” How so? Can you give an example?

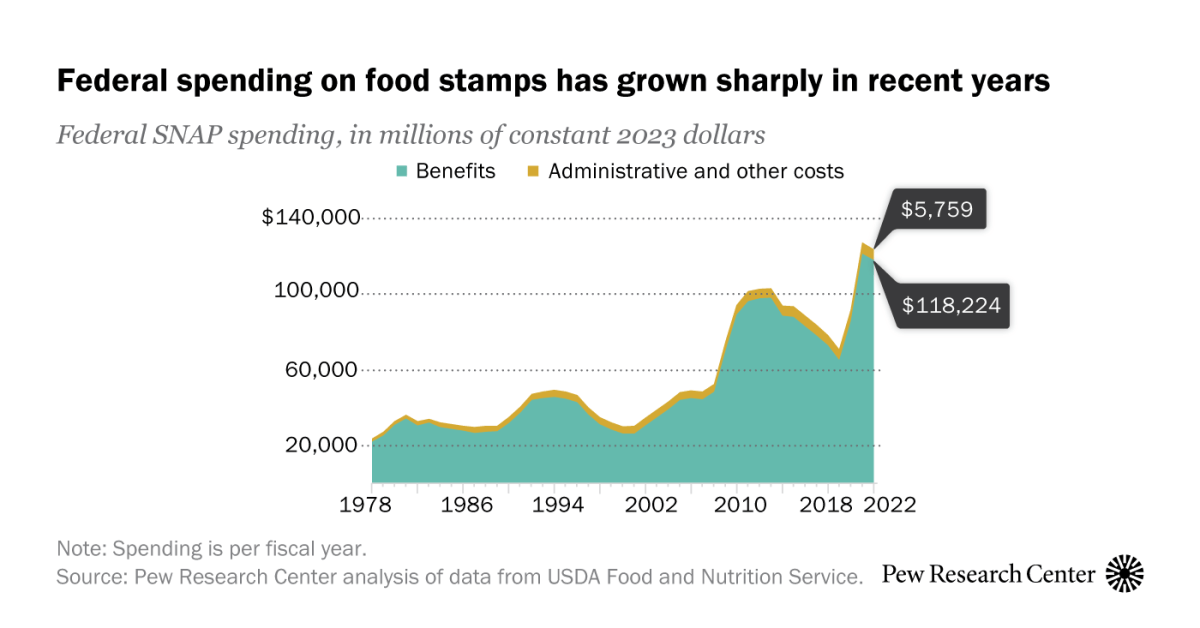

MD: Sure. We have this national entitlement program that’s just not for the poor. In 2020, the nation spent $53 billion on direct housing assistance to the needy, things like public housing or vouchers that reduced rent burden. That same year, we spent over $190 billion on homeowner tax subsidies. Those are things like the home mortgage interest deduction, which homeowners are entitled to. Protecting and fighting for those subsidies leaves less money with which to fight poverty.

AN: So you think there should be fewer tax breaks like the home mortgage interest deduction and more policies to help poor Americans?

MD: I want to be clear: I’m not calling for redistribution. That entails giving up something that is mine and that I’ve earned. What I’m talking about is less rich aid and more poor aid. There was a study published recently showing that if just the top 1% of us just paid the taxes we owe — so not pay more taxes, but just stop evading tax bills — we as a nation could raise $175 billion more every year. That’s almost enough to pull everyone out of poverty.

AN: So getting the IRS to do more enforcement.

MD: Absolutely. When you are trying to fight for ambitious, bold solutions to poverty, you immediately run up against people saying, ‘Well, how will we afford it?’ And the answer is staring us right in the face. We could afford it if we allowed the IRS to do its job.

AN: Thinking that poverty in the U.S. is avoidable makes its existence feel so much worse.We can confront this issue in such a more robust way than we have. And it should shame us that we haven’t.

Matthew Desmond

SOCIOLOGIST AND AUTHOR

MD: It makes it so much worse morally. We are such a rich country. We can confront this issue in such a more robust way than we have. And it should shame us that we haven’t. It should shame us that so many people are living with such uncertainty and agony.

AN: In what way do large companies in the U.S. profit from poverty in America?

MD: As union power started waning, wages started slagging. And then CEO compensation started growing. Corporations have used that economic power and transferred it into political power to make organizing hard and to combat unionization efforts.

AN: As a child, you blamed your father when he lost his job and the bank took your house. Why do you think that was?

MD: When you’re in the middle of something, you often grasp at the explanation that is closest to you, which is often about shame and guilt and blame. When I wrote my last book on families facing evictions, a lot of the families who lost their homes would blame themselves. But I think it’s the sociologist’s job, to quote C. Wright Mills, to turn a personal problem into a political one. Millions of people are facing this every year. This is not on you.

AN: You call on Americans to become “poverty abolitionists.” Why use the word “abolitionists”?

MD: I think that it shares with other abolitionist movements a commitment to the end of poverty. It views poverty not as something that we should get a little better at, but something we should abolish. Because it’s a sin. It’s a disgrace.

AN: What are the most impactful actions people can take to fight poverty?

MD: You can go to your Tuesday night zoning meeting in your community and you can support the affordable housing project that a lot of your neighbors are trying to kill. And you can say, “Look, I’m not going to deny other kids opportunities that my kids have had living here. I’m not going to embrace segregation. That ends with me.” You can shop at places that do right by their workers, and that don’t try to bust unions. There are also all these amazing anti-poverty movements in every state.

AN: I know you don’t have a crystal ball, but if more attention and resources aren’t directed at reducing poverty, what could the future look like for us?

MD: For folks who are struggling, it means a smaller life. It means diminished dreams. It means illnesses that don’t get solved. And for those of us who enjoy some security and prosperity, it means an affront to your sense of decency. If nothing improves, it really belies any claim to national greatness.

Why hasn't U.S. poverty improved in 50 years? Pulitzer-prize winning author Matthew Desmond has an answer

In his new book, "Poverty, by America," Matthew Desmond says that poverty persists in the U.S. because many Americans and large companies profit from it.