Zarvan

ELITE MEMBER

- Joined

- Apr 28, 2011

- Messages

- 54,470

- Reaction score

- 87

- Country

- Location

-

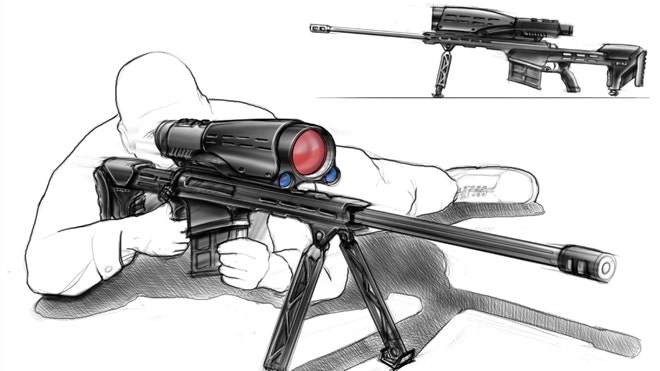

In the action-thriller "The Bourne Legacy," Pentagon black ops assasin Aaron Cross takes down an airborne CIA drone with a rifle from more than a mile away. With TrackingPoint's tech, anyone can perform such a trick. (TRACKINGPOINT)

TrackingPoint borrows the target-locking technology from jets to turn any rifle into a super accurate sniper gun capable of consistently hitting a target at over 1.75 miles. (TRACKINGPOINT)

TRACKINGPOINT

The U.S. military has begun testing several so-called smart rifles made by the applied technology start-up TrackingPoint Inc., company officials said.

The Army is rumored to have acquired six of the precision-guided firearms, which cost as much as $27,000 apiece. Oren Schauble, a marketing official with the Austin, Texas-based company, confirmed the military bought a handful of them in recent months for evaluation. A spokeswoman for the service didn’t immediately respond to an email requesting comment.

'We’re gun nerds, we’re video-game nerds, we’re engineering nerds. Imagine where we’ll be in three to five years.'

- TrackingPoint marketing official Oren Schauble

“The military has purchased several units for testing and evaluation purposes,” Schauble said during an interview with Military.com Tuesday here at the annual SHOT Show, the country’s largest gun show with some 60,000 attendees.]

It’s not hard to see why more than 30 government and law enforcement agencies have requested demonstrations of the potentially game-changing technology since the company debuted the rifle at last year’s show.

Smith & Wesson Unveils Backpack Cannon

With only a few minutes of instruction on the weapon, this correspondent was able to hit a target almost 1,000 yards away on the first shot. Of the 70 or so reporters and other novice shooters who tested the weapon on Monday at a range in Boulder City, Nev., only one or two missed the target, which was located about 980 yards away, according to Schauble.

“That is a better day than usual,” he said. “I would say we’re at about 70 percent first-shot success probability at 1,000 yards … with inexperienced shooters.”

By comparison, military snipers and sharpshooters have a first-shot success rate of between 20 percent and 30 percent, said Schauble, a relative of the firm’s Chief Executive Officer Jason Schauble. They usually reach about 70 percent on subsequent shots, he said.

“That’s the big value proposition,” he said. “There’s a huge gap between first shot and second shot.”

The military testing seeks to determine how typical troops perform using the weapon compared to expert marksman using traditional rifles, Schauble said. The Army has long been excited about the promise of precision-guided, shoulder-fired weapons. Last year, it tested

But it’s unclear what kind of reception the smart rifle will receive in the sniper community. When asked whether the product has encountered resistance from military marksmen, Schauble said, “This is not necessarily for them. This is for guys who don’t have that training who need to perform in greater capabilities. This is more for your average soldier.”

While the company built the rifle for the commercial market, it quickly realized the potential applications for the military and defense sector, especially as battlefields become more networked, Schauble said.

“Rifles can communicate with each other,” he said. “We can enable a more information-driven combat in the sense that you can tag targets. You can pass off those targets to someone else with a scope. There’s a whole layer of communication that comes with having a rifle that can designate and track targets.”

The system includes a Linux-powered computer in the scope with sensors that collect imagery and ballistic data such as atmospheric conditions, cant, inclination, even the slight shift of the Earth’s rotation known as the Coriolis effect. Because the computer is wireless-enabled, information can be streamed to a laptop, smart phone or tablet computer for spotting or to share intelligence.

“The only way to guarantee accuracy is to control all the variables,” said Scott Calvin, a company representative who demonstrated the rifle at the range. The only variable the system doesn’t account for is wind speed and direction, which must be entered manually, he said.

Print Your Prosthetic at Home

The rifle operates far differently than its traditional counterparts, though the process is quite simple.

After looking through the scope, a shooter pushes a red button near the trigger to tag a target — similar to the way a Facebook user tags a friend in a photograph. A reticle then appears based on the bullet’s expected trajectory determined by the computer. The shooter then arms the scope by squeezing the trigger back, lines up the reticle with the painted target and releases the trigger to fire a round.

The rifle may take the art out of marksmanship, but its apparent accuracy is virtually guaranteed to continue to draw interest — not just from customers in the U.S., but around the world. The company has already sold about 500 of the rifles, mostly to wealthy safari hunters and elderly hunters, Schauble said.

Officials from the Agriculture Department stopped by the company’s booth at the show to look at the products for possible use in a program to better control the rising population of feral pigs.

The guns range in cost, from about $10,000 for scope-and-trigger kits installed on semi-automatic Daniel Defense rifles accurate to about 750 yards, to between $22,000 and $27,000 for those installed on bolt-action Surgeon rifles accurate to about 1,250 yards, according to Schauble. The kits can also be installed on other types of firearms, he said.

TrackingPoint was launched about a year ago by John McHale, a founder of multiple technology start-ups, and has about 75 employees, more than half of which are engineers, Schauble said. “We’re gun nerds. We’re video-game nerds. We’re engineering nerds,” he said. “Imagine where we’ll be in three to five years.”

U.S. military begins testing ‘smart’ rifles | Fox News

@Aeronaut @Oscar @nuclearpak @Icarus @WebMaster @RazPaK @mafiya @tarrar @Yzd Khalifa @Arabian Legend @JUBA @al-Hasani @BLACKEAGLE @FARSOLDIER @balixd @Slav Defence @jaibi @DESERT FIGHTER @fatman17 and others

FRED KAPLAN

FRED KAPLAN