India goes to the polls next month to elect a new prime minister. The BJP candidate, and frontrunner, is seen by supporters as a dynamic man of the people. Opponents say he is little more than a rabid nationalist. What would his victory mean?

Narendra Damodar Das Modi strides to the lectern. Thousands are still crossing the open space around the site of the rally. Tens of thousands more are crowding the long road from the fields where hundreds of buses have been haphazardly parked. Then there are the long lines of packed minivans stuck on the highway, only a mile or so from their destination.

There is no more space in the vast bamboo pens in front of the stage set up on this wasteland outside the northern Indian city of Meerut, and police and officials from Modi's Bharatiya Janata (Indian People's) party are turning away latecomers. But only those at the front of the crush know this and those behind quicken their step when they hear the voice of the man they have come to see. Unlike most Indian politicians, Modi is punctual. His rallies start and finish with a minimum of delay.

"As I flew over in the helicopter, it was as if a sea of saffron was beneath me," Modi tells the crowd. Saffron is the colour of the Bharatiya Janata party (BJP), of which he is the candidate in national polls next month, and is powerfully symbolic in Hinduism.

There is a cheer, a guttural roar, from this overwhelmingly male crowd. Meerut is a scruffy, conservative, hardscrabble town surrounded by hundreds of tough, conservative, hardscrabble villages. Some political meetings, in India and elsewhere, are full of hope and confidence, often joyous and celebratory. But not this one.

"I ask forgiveness from those who could not make it to these grounds on time," Modi is saying as the latecomers press forward. Some surge through the bamboo fences into the crowded pens. There are scuffles. The BJP officials haul them out. A constable raises his stick. Modi is now praising Meerut for the role soldiers stationed there played in the 1857 Indian mutiny, or war of independence, against British overlords. Another cheer.

"There is a leader among us who wants to take our country forwards," says Sakshan Shukla, 19, who set out early with his brother from their Meerut home and has found a place close to the stage. "A leader who is honest, who cares for us, who will protect us from the threats against us, who will make us strong. I have come to hear such a leader."

Such words are far from rare now. Yesterday the Indian election commission announced the dates of the coming polls, effectively starting the real campaign for power. The 800 million eligible voters will take six weeks to cast their votes, starting on 7 April. Though the natural drama of democratic process is often drowned in a very Indian alphabet soup of acronyms, this time it is clear the nation is at a pivotal moment.

Modi, 63, is currrently the frontrunner, with surveys repeatedly placing him ahead of 43-year-old Rahul Gandhi, the scion of India's first political family and candidate for the incumbents, the venerable Congress party.

The battle between the two draws sharp lines across the Indian political landscape. Modi is proud to call himself a "Hindu nationalist" and appears to favour radical reform of the country's flagging economy. Gandhi holds true to the leftwing economics and belief in religious pluralism that is the legacy of his great grandfather, Jawarharlal Nehru, the country's first prime minister.

The BJP believes Modi, one of the most polarising figures to walk the Indian political stage for many years, can lead it to a landslide victory, despite opposition claims that he is a demagogue and a "hatemonger". After a false start in 1996, the party won real power for the first time two years later, but lost the 2004 elections. Now BJP strategists believe they have an opportunity to end the long decades of Congress dominance for good – and with it the power of the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty. Insider v outsider, dynast v working-class boy made good, suspected sectarian v secularist: this electoral battle has it all. Some analysts talk of the most significant contest since India won its independence from Britain in 1947.

Modi was born in the dusty temple town of Vadnagar in what is now the western Indian state of Gujarat. His family belonged to the Ghanchi caste, low down on the tenacious social hierarchy that still often defines status in India, and had little money. As a boy, Modi helped out on his father's tea stall before his lessons at a government school where he was neither an outstanding student nor particularly sociable. He was, however, fastidious, opinionated and, says his biographer Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay, "rebellious". The late 1960s were times of great ferment in India, as the country struggled with massive economic problems and was riven by ideological battles. By the time he was 10, Modi was attending the early-morning outdoor drill meetings held by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS, National Volunteer Organisation), the highly disciplined rightwing organisation dedicated to realising a nationalist, traditionalist and religious vision of India's future. When he left university, he became a full-time RSS activist, a pracharak, sworn to a celibate, teetotal, vegetarian life of organisation and propaganda. According to Indian news reports that have not been officially denied, an early arranged marriage was quietly forgotten. Modi's first job was sweeping the local offices, which he did with customary dedication and efficiency. He worked hard and rose rapidly.

The RSS, which has around 40 million members, was, and still is, controversial. The organisation was banned in the aftermath of Mohandas Gandhi's killing by a Hindu fanatic in 1948, and again during the Emergency, a two-year suspension of democracy by Indira Gandhi, Rahul's grandmother, in the 1970s. During this time, Modi worked underground. A third ban came after the destruction of a mosque on a contested site in Ayodhya, a northern city, by Hindu extremists in 1992.

By then Modi had transferred to the BJP, which is ideologically close but organisationally distinct from the RSS. In 2001 he replaced a rival within the BJP to become the chief minister of his home state.

Now that Modi is a prime-ministerial candidate, the argument over the lessons that can be drawn from his 12-year-plus reign in Gujarat has intensified. Supporters say his achievements in the state demonstrate his ability to get things done. Modi has successfully pushed through major projects, such as a vast reconstruction of the centre of Gujarat's biggest city, Ahmedabad, and presided over a tripling of the size of Gujarat's economy. Local and international firms are queuing up to invest, power supply has improved significantly and exports have soared.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, all this, along with generous tax breaks, has made Modi a corporate favourite. "If we'd had a Modi running the nation instead of the crew we've had to suffer for the last decade, I'd be a lot better off, and so would everyone else," said one major industrialist and hotelier from the northern state of Punjab who, likely many interviewed for this article, preferred to remain anonymous. A media tycoon in Delhi described Modi bluntly as "the only man who can get us out of the hole we are now in".

Modi's apparent executive ability contrasts dramatically with the squabbling, ineffectual Congress-led coalitions in power at a national level since 2004. Support for the incumbents has been battered by the slowdown in India's booming economy in recent years, runaway inflation and successive corruption scandals. In a political world vitiated by graft allegations, no one, not even his fiercest opponents, has accused Modi of any interest in personal material gain, whether licit or illicit.

But there are many criticisms too. Both Modi's claims of economic achievement and his cosiness with India's so-called "croney capitalists" are frequently questioned. Many say growth in Gujarat is no greater than that in several other states in India and is considerably less well-distributed. Amartya Sen, the Nobel laureate economist, has said the state's social and economic progress is poor. Others claim that keeping growth at healthy levels in Gujarat, a mid-sized state with a strong tradition of trade and a better infrastructure than much of the country, is easier than elsewhere. The chief minister's executive ability is not a result of administrative skill, some argue, but of deep, aggressively authoritarian instincts. In Gujarat, journalists in Ahmedabad say, simple intimidation has reduced the press corps to cowed servility. Modi is not a man who patiently builds consensus. He does not, it appears, like to be challenged.

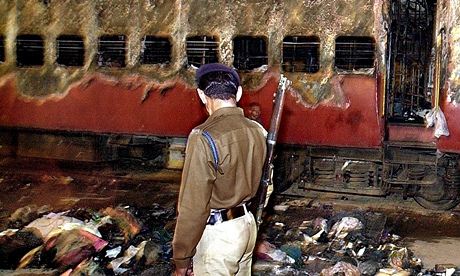

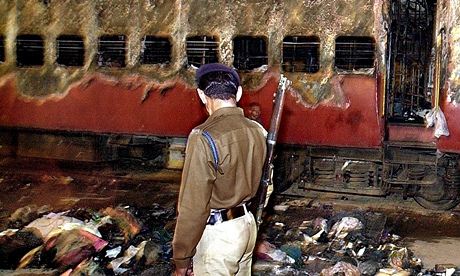

But it is not economics, nor even his alleged dictatorial tendencies, that makes Modi such a polarising figure. It is violence, and specifically an outbreak of rioting in Gujarat in 2002 triggered by the deaths of 59 Hindu pilgrims after their train was torched in a largely Muslim town. Of the thousand or more killed and hundreds of thousands forced out of their homes in the chaos that followed, most were Muslims.

Modi, who had just taken over power when the riots occurred, recently described his "pain" during the episode. Yet he has never apologised for his failure to protect the minority community. Repeatedly accused of allowing, even encouraging, Hindus whipped up by hardline activists to vent their fury, Modi has consistently denied all wrongdoing and has been cleared by a succession of high-powered legal inquiries. It was after a key court decision that the UK decided in 2012 to end a boycott of Modi by senior officials. Only weeks ago, the US followed. Nonetheless, Modi has yet to shake off the controversy.

There are many reasons for this. India has long been prone to periodic bouts of communal violence, and political opponents, cynically or otherwise, repeatedly cite the 2002 rioting to highlight the threat of sectarian conflict if Modi wins the coming elections. Though Modi has not been convicted, they point out, associates have been sent to prison for their role in the violence. There are also many ordinary Indians, and not just India's Muslim minority, who are deeply committed to a tolerant, pluralist, progressive vision of India and who believe Modi would divide and damage their country.

Others see things differently. For tens, perhaps hundreds of millions of people across India, what happened in 2002, or at least what they believe happened, does not so much raise doubts about Modi's claim to lead the country, but reinforce it.

In a school run by the RSS close to the Meerut rally site, on the eve of the meeting, members of the organisation gathered for a conference on encouraging traditional sports. Their worldview is nationalist and conservative. Incidents such as the 2012 gang rape and murder of a 23-year-old woman on a bus in Delhi are a result of "moral decadence" and western culture, they say, while the boundaries of "Bharat", the Sanskrit-origin word they use to describe their country, should encompass Afghanistan, Pakistan, Tibet, Bangladesh and Burma. One veteran claims India faces three problems: "corruption, inflation and Muslims". Modi has an answer to all three, he insists. Rajendra Agrawal, the BJP member of parliament representing Meerut's 1.4 million voters, stresses that Hinduism's message is one of peace and tolerance but "one day … Islamic aggression will have to be dealt with".

A key question is how far Modi has moved from the hardline vision of the organisation he joined at the age of 10. In recent years, there have been tensions between the politician and the RSS. The candidate's pragmatic, business-friendly, globalised outlook is at odds with the traditional self-reliance of the nationalist movement. The RSS did not take it well, either, when Modi suggested that India needed to build toilets before temples.

Christophe Jaffrelot, a political scientist who specialises in extremism in south Asia, says Modi has effectively "emancipated himself" from the RSS high command, who traditionally outrank even senior BJP figures. Yet, he adds, Modi may well "do anyway what the RSS has wanted to do for decades because he is perfectly in tune with their ideology."

How much of that programme Modi will implement depends, Jaffrelot said, on how much power he has. And that depends on how many seats he gets and how many parties he has to work with to form a coalition.

Strategists working for Modi and the BJP know that Uttar Pradesh, the northern state with a population of nearly 200 million that sends 80 representatives to the 545-seat lower house, is critical to the party's declared aim of securing a majority. This is why Modi has come to Meerut, a typical Uttar Pradesh city with typical Uttar Pradesh problems.

Though only 50 miles from Delhi, Meerut is a zone of transition. Those who live there are caught between the country and the city, old poverty and new wealth, traditional values and "modernity", old communities and individual pleasures, fear and hope, scarcity and aspiration. Drive through Meerut and it is clear that much has changed in recent years but little has been completed, other than perhaps a bypass, a mall and a new four-star hotel.

There has been progress in Meerut of course. People are, on the whole, less poor than they were. The local literacy rate has now risen to around 75%, though progress has slowed in the last decade. Due to a preference for sons followed by widespread discrimination in youth and adult life, there were 886 women to every 1,000 men in 2011 – a slight improvement on 2001 when the previous census had been done. There are more power, sewage and water connections and water than a decade ago, though still nowhere near enough. The rate of population growth has slowed, though less than in wealthier and better educated parts of the country. In India, two thirds of the population is under 35. The coming election will see 150 million first-time voters. In Meerut, the median age is even lower than the national average. There are nowhere near enough jobs.

The result in Meerut is very large numbers of young men, on the streets, in the bus station, around the university, outside the Hair Fixing Centre and the IDEA High Speed Internet Store, outside the shabby cinema where posters advertising the latest Bollywood blockbusters peel from mouldering walls.

In the mall, open only three months, business is slow. Michael Jackson's Thriller blasts through the echoing halls. Few locals have 2,000 Rupees (£20) for a pair of jeans on sale in Numero Uno clothes shop. The manager, 25-year-old Mukesh Verma, says he will vote for Modi who, he thinks, "will do something for the new generation" and "make India a strong country again". Down in the centre of Meerut, there is much talk of "opportunity", of "removing corruption", of "government jobs", of national pride. Some travel four hours on overloaded busses every day to Delhi and back to study or work. Others, including graduates, eke a living from intermittent labouring jobs or teach in the unregistered, sub-standard "colleges" that have proliferated on the outskirts of the city. Many simply spend their days "doing timepass", a word that Oxford University geography Professor Craig Jeffrey, who has done research in Meerut, uses to sum up both the numbing tedium of their lives and their sense of being economically detached and politically disengaged.

"This place is stagnant, left behind," says Archana Sharma, a political science professor at Meerut's main university. "The poor people now feel it is a question of their own survival. The business community, the middle section of society, are all very worried about security. They want someone who will bring fair, firm administration."

But there is another dynamic also at work, specific to the town. Talk to people in Meerut about Modi and a divide becomes very obvious, very quickly. In the shopping mall, Javed and Furqan, both 19, say they will vote for Rahul Gandhi. Both are Muslim. "There is tension in the mind about the future otherwise," Furqan says quietly. In a park, Mohammed and Azaruddin, teenagers working in a local sports goods factory, but spending a Saturday afternoon "doing timepass", look worried when Modi is mentioned and walk quickly away. In a shabby mosque, Mobeen Ahmed, an Islamic studies teacher, first claims that "communal relations are good and harmonious" in Meerut, then says he has "no idea" what sparked the sectarian violence which killed 64 people a month or so previously just 40 miles to the north. Finally he says that "if Modi could deal out injustice in Gujarat, he could to it as prime minister too".

Even his detractors admit that Modi is a formidable public speaker. In smaller meetings, he varies his tone from the confidential to the triumphant depending on the audience. When he speaks to the crowd in Meerut, his tone is simply angry.

"Even now, more than 150 years after the rebellion of 1857, we have to fight for roti [bread] in the houses of the poor. The date of this rebellion is important yet this government did not see that importance. Congress has forgotten the number of young people who gave their lives for the 1857 rebellion. But we must remember them."

In three sentences Modi has touched on national pride, the anti-colonial struggle, continuing poverty, youth, sacrifice and disappointment. He talks about a key 19th-century reformist Hindu scholar and activist, Dayananda Saraswati, whose message, he says, is relevant today and then turns to Meerut. The town, Modi says, has been left behind.

"Do you get power 24 hours a day? If your mother is unwell can you switch on a fan? If your son has exams can you turn on the light so he can study? When the British were here they saw the people of Meerut as enemies … but your own government? Why does Meerut not get roads, railways, an airport? What has Meerut done? What is Meerut's crime?" Modi thunders. There is a growl of assent from the crowd.

"Do you believe your sisters and mothers are safe?" Modi asks. "When your daughter goes out, do you think she will come back and say: 'Daddy, nobody troubled me'? Terrorists and criminals are rewarded in this state these days. In Meerut, there is a riot all the time. Ten years ago, in Gujarat, there used to be many riots. But now the people of Gujarat know they have to live in peace, to live free from the politics of polarisation. They know they have to take the path of development. And all is calm."

Another growl, applause, and scattered cheers. And so it continues, for 49 of the scheduled 50 minutes. There are further references to violent crime, to youth unemployment, to the bribes that have to be paid to secure jobs, and then a sudden, ferocious attack on the Congress party. First Modi quotes Rahul Gandhi, who told a recent rally of how his mother, party president, chair of the ruling coalition and widow of an assassinated prime minister, had cried as she told him that "power was poison".

"Who has been in power most of these last 60 years?" he asks, building in volume.

"If power is poison, who has taken most? Who has a stomach full of poison? Who is vomiting it out now? It is Congress, the party which divides and rules, which pits one religion against another, states against states, which is breaking the country."

"Brothers, sisters," Modi cries. "Enough poison, enough of the politics of poison. We need the politics of development, so the poor need welfare, the young get jobs, mothers and sisters get respect."

He pauses, then calls out: "Time is running out. Promise me you will change this nation. Clench your fists. Say it with all your might: 'Vote for India.'"

The vast crowd on the outskirts of the troubled city in one of the most troubled parts of the nation do what Modi tells them. They raise their arms, clench their fists in the air and, again and again, come the ragged shouts of "Vote for India".

One evening, a few days later, Modi makes an appearance at a society wedding reception at a five-star hotel in Delhi's diplomatic quarter. It is a gathering of Delhi's power elite. Cabinet ministers, chief ministers, the senior ranks of the BJP, millionaire businessmen, famous academics and newspaper editors have gathered to gossip, eat and drink.

Smaller, stouter than he looks on a stage, Modi, avuncular if slightly preoccupied, greets the bride and groom and then makes a slow progress through the guests. He is preceded by a small swarm of backpedalling supplicants. An ambassador introduces himself and his bejewelled wife, insisting that he is "so pleased to meet" him and that his country is "such a dear friend of India". Modi nods graciously and moves on. There is a brief exchange with a media mogul, and with me. The Meerut rally was a success, he indicates, making an odd gesture, part invocation, part assertion, with a hand pointing heavenwards. He stands with a clutch of middle-aged ladies as pictures are taken, poses for a selfie with a teenager and pats children, slightly uneasily, on the head. Then he excuses himself, turns and strides purposefully through the hotel lobby, trailed by his Gujarati security detail, and disappears into the chill northern Indian night.

Narendra Modi: India's saviour or its worst nightmare? | World news | The Guardian

Narendra Damodar Das Modi strides to the lectern. Thousands are still crossing the open space around the site of the rally. Tens of thousands more are crowding the long road from the fields where hundreds of buses have been haphazardly parked. Then there are the long lines of packed minivans stuck on the highway, only a mile or so from their destination.

There is no more space in the vast bamboo pens in front of the stage set up on this wasteland outside the northern Indian city of Meerut, and police and officials from Modi's Bharatiya Janata (Indian People's) party are turning away latecomers. But only those at the front of the crush know this and those behind quicken their step when they hear the voice of the man they have come to see. Unlike most Indian politicians, Modi is punctual. His rallies start and finish with a minimum of delay.

"As I flew over in the helicopter, it was as if a sea of saffron was beneath me," Modi tells the crowd. Saffron is the colour of the Bharatiya Janata party (BJP), of which he is the candidate in national polls next month, and is powerfully symbolic in Hinduism.

There is a cheer, a guttural roar, from this overwhelmingly male crowd. Meerut is a scruffy, conservative, hardscrabble town surrounded by hundreds of tough, conservative, hardscrabble villages. Some political meetings, in India and elsewhere, are full of hope and confidence, often joyous and celebratory. But not this one.

"I ask forgiveness from those who could not make it to these grounds on time," Modi is saying as the latecomers press forward. Some surge through the bamboo fences into the crowded pens. There are scuffles. The BJP officials haul them out. A constable raises his stick. Modi is now praising Meerut for the role soldiers stationed there played in the 1857 Indian mutiny, or war of independence, against British overlords. Another cheer.

"There is a leader among us who wants to take our country forwards," says Sakshan Shukla, 19, who set out early with his brother from their Meerut home and has found a place close to the stage. "A leader who is honest, who cares for us, who will protect us from the threats against us, who will make us strong. I have come to hear such a leader."

Such words are far from rare now. Yesterday the Indian election commission announced the dates of the coming polls, effectively starting the real campaign for power. The 800 million eligible voters will take six weeks to cast their votes, starting on 7 April. Though the natural drama of democratic process is often drowned in a very Indian alphabet soup of acronyms, this time it is clear the nation is at a pivotal moment.

Modi, 63, is currrently the frontrunner, with surveys repeatedly placing him ahead of 43-year-old Rahul Gandhi, the scion of India's first political family and candidate for the incumbents, the venerable Congress party.

The battle between the two draws sharp lines across the Indian political landscape. Modi is proud to call himself a "Hindu nationalist" and appears to favour radical reform of the country's flagging economy. Gandhi holds true to the leftwing economics and belief in religious pluralism that is the legacy of his great grandfather, Jawarharlal Nehru, the country's first prime minister.

The BJP believes Modi, one of the most polarising figures to walk the Indian political stage for many years, can lead it to a landslide victory, despite opposition claims that he is a demagogue and a "hatemonger". After a false start in 1996, the party won real power for the first time two years later, but lost the 2004 elections. Now BJP strategists believe they have an opportunity to end the long decades of Congress dominance for good – and with it the power of the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty. Insider v outsider, dynast v working-class boy made good, suspected sectarian v secularist: this electoral battle has it all. Some analysts talk of the most significant contest since India won its independence from Britain in 1947.

Modi was born in the dusty temple town of Vadnagar in what is now the western Indian state of Gujarat. His family belonged to the Ghanchi caste, low down on the tenacious social hierarchy that still often defines status in India, and had little money. As a boy, Modi helped out on his father's tea stall before his lessons at a government school where he was neither an outstanding student nor particularly sociable. He was, however, fastidious, opinionated and, says his biographer Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay, "rebellious". The late 1960s were times of great ferment in India, as the country struggled with massive economic problems and was riven by ideological battles. By the time he was 10, Modi was attending the early-morning outdoor drill meetings held by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS, National Volunteer Organisation), the highly disciplined rightwing organisation dedicated to realising a nationalist, traditionalist and religious vision of India's future. When he left university, he became a full-time RSS activist, a pracharak, sworn to a celibate, teetotal, vegetarian life of organisation and propaganda. According to Indian news reports that have not been officially denied, an early arranged marriage was quietly forgotten. Modi's first job was sweeping the local offices, which he did with customary dedication and efficiency. He worked hard and rose rapidly.

The RSS, which has around 40 million members, was, and still is, controversial. The organisation was banned in the aftermath of Mohandas Gandhi's killing by a Hindu fanatic in 1948, and again during the Emergency, a two-year suspension of democracy by Indira Gandhi, Rahul's grandmother, in the 1970s. During this time, Modi worked underground. A third ban came after the destruction of a mosque on a contested site in Ayodhya, a northern city, by Hindu extremists in 1992.

By then Modi had transferred to the BJP, which is ideologically close but organisationally distinct from the RSS. In 2001 he replaced a rival within the BJP to become the chief minister of his home state.

Now that Modi is a prime-ministerial candidate, the argument over the lessons that can be drawn from his 12-year-plus reign in Gujarat has intensified. Supporters say his achievements in the state demonstrate his ability to get things done. Modi has successfully pushed through major projects, such as a vast reconstruction of the centre of Gujarat's biggest city, Ahmedabad, and presided over a tripling of the size of Gujarat's economy. Local and international firms are queuing up to invest, power supply has improved significantly and exports have soared.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, all this, along with generous tax breaks, has made Modi a corporate favourite. "If we'd had a Modi running the nation instead of the crew we've had to suffer for the last decade, I'd be a lot better off, and so would everyone else," said one major industrialist and hotelier from the northern state of Punjab who, likely many interviewed for this article, preferred to remain anonymous. A media tycoon in Delhi described Modi bluntly as "the only man who can get us out of the hole we are now in".

Modi's apparent executive ability contrasts dramatically with the squabbling, ineffectual Congress-led coalitions in power at a national level since 2004. Support for the incumbents has been battered by the slowdown in India's booming economy in recent years, runaway inflation and successive corruption scandals. In a political world vitiated by graft allegations, no one, not even his fiercest opponents, has accused Modi of any interest in personal material gain, whether licit or illicit.

But there are many criticisms too. Both Modi's claims of economic achievement and his cosiness with India's so-called "croney capitalists" are frequently questioned. Many say growth in Gujarat is no greater than that in several other states in India and is considerably less well-distributed. Amartya Sen, the Nobel laureate economist, has said the state's social and economic progress is poor. Others claim that keeping growth at healthy levels in Gujarat, a mid-sized state with a strong tradition of trade and a better infrastructure than much of the country, is easier than elsewhere. The chief minister's executive ability is not a result of administrative skill, some argue, but of deep, aggressively authoritarian instincts. In Gujarat, journalists in Ahmedabad say, simple intimidation has reduced the press corps to cowed servility. Modi is not a man who patiently builds consensus. He does not, it appears, like to be challenged.

But it is not economics, nor even his alleged dictatorial tendencies, that makes Modi such a polarising figure. It is violence, and specifically an outbreak of rioting in Gujarat in 2002 triggered by the deaths of 59 Hindu pilgrims after their train was torched in a largely Muslim town. Of the thousand or more killed and hundreds of thousands forced out of their homes in the chaos that followed, most were Muslims.

Modi, who had just taken over power when the riots occurred, recently described his "pain" during the episode. Yet he has never apologised for his failure to protect the minority community. Repeatedly accused of allowing, even encouraging, Hindus whipped up by hardline activists to vent their fury, Modi has consistently denied all wrongdoing and has been cleared by a succession of high-powered legal inquiries. It was after a key court decision that the UK decided in 2012 to end a boycott of Modi by senior officials. Only weeks ago, the US followed. Nonetheless, Modi has yet to shake off the controversy.

There are many reasons for this. India has long been prone to periodic bouts of communal violence, and political opponents, cynically or otherwise, repeatedly cite the 2002 rioting to highlight the threat of sectarian conflict if Modi wins the coming elections. Though Modi has not been convicted, they point out, associates have been sent to prison for their role in the violence. There are also many ordinary Indians, and not just India's Muslim minority, who are deeply committed to a tolerant, pluralist, progressive vision of India and who believe Modi would divide and damage their country.

Others see things differently. For tens, perhaps hundreds of millions of people across India, what happened in 2002, or at least what they believe happened, does not so much raise doubts about Modi's claim to lead the country, but reinforce it.

In a school run by the RSS close to the Meerut rally site, on the eve of the meeting, members of the organisation gathered for a conference on encouraging traditional sports. Their worldview is nationalist and conservative. Incidents such as the 2012 gang rape and murder of a 23-year-old woman on a bus in Delhi are a result of "moral decadence" and western culture, they say, while the boundaries of "Bharat", the Sanskrit-origin word they use to describe their country, should encompass Afghanistan, Pakistan, Tibet, Bangladesh and Burma. One veteran claims India faces three problems: "corruption, inflation and Muslims". Modi has an answer to all three, he insists. Rajendra Agrawal, the BJP member of parliament representing Meerut's 1.4 million voters, stresses that Hinduism's message is one of peace and tolerance but "one day … Islamic aggression will have to be dealt with".

A key question is how far Modi has moved from the hardline vision of the organisation he joined at the age of 10. In recent years, there have been tensions between the politician and the RSS. The candidate's pragmatic, business-friendly, globalised outlook is at odds with the traditional self-reliance of the nationalist movement. The RSS did not take it well, either, when Modi suggested that India needed to build toilets before temples.

Christophe Jaffrelot, a political scientist who specialises in extremism in south Asia, says Modi has effectively "emancipated himself" from the RSS high command, who traditionally outrank even senior BJP figures. Yet, he adds, Modi may well "do anyway what the RSS has wanted to do for decades because he is perfectly in tune with their ideology."

How much of that programme Modi will implement depends, Jaffrelot said, on how much power he has. And that depends on how many seats he gets and how many parties he has to work with to form a coalition.

Strategists working for Modi and the BJP know that Uttar Pradesh, the northern state with a population of nearly 200 million that sends 80 representatives to the 545-seat lower house, is critical to the party's declared aim of securing a majority. This is why Modi has come to Meerut, a typical Uttar Pradesh city with typical Uttar Pradesh problems.

Though only 50 miles from Delhi, Meerut is a zone of transition. Those who live there are caught between the country and the city, old poverty and new wealth, traditional values and "modernity", old communities and individual pleasures, fear and hope, scarcity and aspiration. Drive through Meerut and it is clear that much has changed in recent years but little has been completed, other than perhaps a bypass, a mall and a new four-star hotel.

There has been progress in Meerut of course. People are, on the whole, less poor than they were. The local literacy rate has now risen to around 75%, though progress has slowed in the last decade. Due to a preference for sons followed by widespread discrimination in youth and adult life, there were 886 women to every 1,000 men in 2011 – a slight improvement on 2001 when the previous census had been done. There are more power, sewage and water connections and water than a decade ago, though still nowhere near enough. The rate of population growth has slowed, though less than in wealthier and better educated parts of the country. In India, two thirds of the population is under 35. The coming election will see 150 million first-time voters. In Meerut, the median age is even lower than the national average. There are nowhere near enough jobs.

The result in Meerut is very large numbers of young men, on the streets, in the bus station, around the university, outside the Hair Fixing Centre and the IDEA High Speed Internet Store, outside the shabby cinema where posters advertising the latest Bollywood blockbusters peel from mouldering walls.

In the mall, open only three months, business is slow. Michael Jackson's Thriller blasts through the echoing halls. Few locals have 2,000 Rupees (£20) for a pair of jeans on sale in Numero Uno clothes shop. The manager, 25-year-old Mukesh Verma, says he will vote for Modi who, he thinks, "will do something for the new generation" and "make India a strong country again". Down in the centre of Meerut, there is much talk of "opportunity", of "removing corruption", of "government jobs", of national pride. Some travel four hours on overloaded busses every day to Delhi and back to study or work. Others, including graduates, eke a living from intermittent labouring jobs or teach in the unregistered, sub-standard "colleges" that have proliferated on the outskirts of the city. Many simply spend their days "doing timepass", a word that Oxford University geography Professor Craig Jeffrey, who has done research in Meerut, uses to sum up both the numbing tedium of their lives and their sense of being economically detached and politically disengaged.

"This place is stagnant, left behind," says Archana Sharma, a political science professor at Meerut's main university. "The poor people now feel it is a question of their own survival. The business community, the middle section of society, are all very worried about security. They want someone who will bring fair, firm administration."

But there is another dynamic also at work, specific to the town. Talk to people in Meerut about Modi and a divide becomes very obvious, very quickly. In the shopping mall, Javed and Furqan, both 19, say they will vote for Rahul Gandhi. Both are Muslim. "There is tension in the mind about the future otherwise," Furqan says quietly. In a park, Mohammed and Azaruddin, teenagers working in a local sports goods factory, but spending a Saturday afternoon "doing timepass", look worried when Modi is mentioned and walk quickly away. In a shabby mosque, Mobeen Ahmed, an Islamic studies teacher, first claims that "communal relations are good and harmonious" in Meerut, then says he has "no idea" what sparked the sectarian violence which killed 64 people a month or so previously just 40 miles to the north. Finally he says that "if Modi could deal out injustice in Gujarat, he could to it as prime minister too".

Even his detractors admit that Modi is a formidable public speaker. In smaller meetings, he varies his tone from the confidential to the triumphant depending on the audience. When he speaks to the crowd in Meerut, his tone is simply angry.

"Even now, more than 150 years after the rebellion of 1857, we have to fight for roti [bread] in the houses of the poor. The date of this rebellion is important yet this government did not see that importance. Congress has forgotten the number of young people who gave their lives for the 1857 rebellion. But we must remember them."

In three sentences Modi has touched on national pride, the anti-colonial struggle, continuing poverty, youth, sacrifice and disappointment. He talks about a key 19th-century reformist Hindu scholar and activist, Dayananda Saraswati, whose message, he says, is relevant today and then turns to Meerut. The town, Modi says, has been left behind.

"Do you get power 24 hours a day? If your mother is unwell can you switch on a fan? If your son has exams can you turn on the light so he can study? When the British were here they saw the people of Meerut as enemies … but your own government? Why does Meerut not get roads, railways, an airport? What has Meerut done? What is Meerut's crime?" Modi thunders. There is a growl of assent from the crowd.

"Do you believe your sisters and mothers are safe?" Modi asks. "When your daughter goes out, do you think she will come back and say: 'Daddy, nobody troubled me'? Terrorists and criminals are rewarded in this state these days. In Meerut, there is a riot all the time. Ten years ago, in Gujarat, there used to be many riots. But now the people of Gujarat know they have to live in peace, to live free from the politics of polarisation. They know they have to take the path of development. And all is calm."

Another growl, applause, and scattered cheers. And so it continues, for 49 of the scheduled 50 minutes. There are further references to violent crime, to youth unemployment, to the bribes that have to be paid to secure jobs, and then a sudden, ferocious attack on the Congress party. First Modi quotes Rahul Gandhi, who told a recent rally of how his mother, party president, chair of the ruling coalition and widow of an assassinated prime minister, had cried as she told him that "power was poison".

"Who has been in power most of these last 60 years?" he asks, building in volume.

"If power is poison, who has taken most? Who has a stomach full of poison? Who is vomiting it out now? It is Congress, the party which divides and rules, which pits one religion against another, states against states, which is breaking the country."

"Brothers, sisters," Modi cries. "Enough poison, enough of the politics of poison. We need the politics of development, so the poor need welfare, the young get jobs, mothers and sisters get respect."

He pauses, then calls out: "Time is running out. Promise me you will change this nation. Clench your fists. Say it with all your might: 'Vote for India.'"

The vast crowd on the outskirts of the troubled city in one of the most troubled parts of the nation do what Modi tells them. They raise their arms, clench their fists in the air and, again and again, come the ragged shouts of "Vote for India".

One evening, a few days later, Modi makes an appearance at a society wedding reception at a five-star hotel in Delhi's diplomatic quarter. It is a gathering of Delhi's power elite. Cabinet ministers, chief ministers, the senior ranks of the BJP, millionaire businessmen, famous academics and newspaper editors have gathered to gossip, eat and drink.

Smaller, stouter than he looks on a stage, Modi, avuncular if slightly preoccupied, greets the bride and groom and then makes a slow progress through the guests. He is preceded by a small swarm of backpedalling supplicants. An ambassador introduces himself and his bejewelled wife, insisting that he is "so pleased to meet" him and that his country is "such a dear friend of India". Modi nods graciously and moves on. There is a brief exchange with a media mogul, and with me. The Meerut rally was a success, he indicates, making an odd gesture, part invocation, part assertion, with a hand pointing heavenwards. He stands with a clutch of middle-aged ladies as pictures are taken, poses for a selfie with a teenager and pats children, slightly uneasily, on the head. Then he excuses himself, turns and strides purposefully through the hotel lobby, trailed by his Gujarati security detail, and disappears into the chill northern Indian night.

Narendra Modi: India's saviour or its worst nightmare? | World news | The Guardian

. Never mind no one in India give two rats what these propaganda machines think about Modi or India.

. Never mind no one in India give two rats what these propaganda machines think about Modi or India.