How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Military UAV Designs

- Thread starter Manticore

- Start date

octopusonhead

FULL MEMBER

New Recruit

- Joined

- Jan 10, 2013

- Messages

- 49

- Reaction score

- 0

- Country

- Location

Now I can see why their have been so many UFO sightings in the past.

Argus Panoptes

BANNED

- Joined

- Feb 13, 2013

- Messages

- 4,065

- Reaction score

- 0

Micro Air Vehicles (MAVs): The next generation of drones

The Drones Come Home

Unmanned aircraft have proved their prowess against al Qaeda. Now they’re poised to take off on the home front. Possible missions: patrolling borders, tracking perps, dusting crops. And maybe watching us all?

By John Horgan

Photograph by Joe McNally

At the edge of a stubbly, dried-out alfalfa field outside Grand Junction, Colorado, Deputy Sheriff Derek Johnson, a stocky young man with a buzz cut, squints at a speck crawling across the brilliant, hazy sky. It’s not a vulture or crow but a Falcon—a new brand of unmanned aerial vehicle, or drone, and Johnson is flying it. The sheriff ’s office here in Mesa County, a plateau of farms and ranches corralled by bone-hued mountains, is weighing the Falcon’s potential for spotting lost hikers and criminals on the lam. A laptop on a table in front of Johnson shows the drone’s flickering images of a nearby highway.

Standing behind Johnson, watching him watch the Falcon, is its designer, Chris Miser. Rock-jawed, arms crossed, sunglasses pushed atop his shaved head, Miser is a former Air Force captain who worked on military drones before quitting in 2007 to found his own company in Aurora, Colorado. The Falcon has an eight-foot wingspan but weighs just 9.5 pounds. Powered by an electric motor, it carries two swiveling cameras, visible and infrared, and a GPS-guided autopilot. Sophisticated enough that it can’t be exported without a U.S. government license, the Falcon is roughly comparable, Miser says, to the Raven, a hand-launched military drone—but much cheaper. He plans to sell two drones and support equipment for about the price of a squad car.

A law signed by President Barack Obama in February 2012 directs the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to throw American airspace wide open to drones by September 30, 2015. But for now Mesa County, with its empty skies, is one of only a few jurisdictions with an FAA permit to fly one. The sheriff ’s office has a three-foot-wide helicopter drone called a Draganflyer, which stays aloft for just 20 minutes.

The Falcon can fly for an hour, and it’s easy to operate. “You just put in the coordinates, and it flies itself,” says Benjamin Miller, who manages the unmanned aircraft program for the sheriff ’s office. To navigate, Johnson types the desired altitude and airspeed into the laptop and clicks targets on a digital map; the autopilot does the rest. To launch the Falcon, you simply hurl it into the air. An accelerometer switches on the propeller only after the bird has taken flight, so it won’t slice the hand that launches it.

The stench from a nearby chicken-processing plant wafts over the alfalfa field. “Let’s go ahead and tell it to land,” Miser says to Johnson. After the deputy sheriff clicks on the laptop, the Falcon swoops lower, releases a neon orange parachute, and drifts gently to the ground, just yards from the spot Johnson clicked on. “The Raven can’t do that,” Miser says proudly.

Offspring of 9/11

A dozen years ago only two communities cared much about drones. One was hobbyists who flew radio-controlled planes and choppers for fun. The other was the military, which carried out surveillance missions with unmanned aircraft like the General Atomics Predator.

Then came 9/11, followed by the U.S. invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, and drones rapidly became an essential tool of the U.S. armed forces. The Pentagon armed the Predator and a larger unmanned surveillance plane, the Reaper, with missiles, so that their operators—sitting in offices in places like Nevada or New York—could destroy as well as spy on targets thousands of miles away. Aerospace firms churned out a host of smaller drones with increasingly clever computer chips and keen sensors—cameras but also instruments that measure airborne chemicals, pathogens, radioactive materials.

The U.S. has deployed more than 11,000 military drones, up from fewer than 200 in 2002. They carry out a wide variety of missions while saving money and American lives. Within a generation they could replace most manned military aircraft, says John Pike, a defense expert at the think tank GlobalSecurity.org. Pike suspects that the F-35 Lightning II, now under development by Lockheed Martin, might be “the last fighter with an ejector seat, and might get converted into a drone itself.”

At least 50 other countries have drones, and some, notably China, Israel, and Iran, have their own manufacturers. Aviation firms—as well as university and government researchers—are designing a flock of next-generation aircraft, ranging in size from robotic moths and hummingbirds to Boeing’s Phantom Eye, a hydrogen-fueled behemoth with a 150-foot wingspan that can cruise at 65,000 feet for up to four days.

More than a thousand companies, from tiny start-ups like Miser’s to major defense contractors, are now in the drone business—and some are trying to steer drones into the civilian world. Predators already help Customs and Border Protection agents spot smugglers and illegal immigrants sneaking into the U.S. NASA-operated Global Hawks record atmospheric data and peer into hurricanes. Drones have helped scientists gather data on volcanoes in Costa Rica, archaeological sites in Russia and Peru, and flooding in North Dakota.

So far only a dozen police departments, including ones in Miami and Seattle, have applied to the FAA for permits to fly drones. But drone advocates—who generally prefer the term UAV, for unmanned aerial vehicle—say all 18,000 law enforcement agencies in the U.S. are potential customers. They hope UAVs will soon become essential too for agriculture (checking and spraying crops, finding lost cattle), journalism (scoping out public events or celebrity backyards), weather forecasting, traffic control. “The sky’s the limit, pun intended,” says Bill Borgia, an engineer at Lockheed Martin. “Once we get UAVs in the hands of potential users, they’ll think of lots of cool applications.”

The biggest obstacle, advocates say, is current FAA rules, which tightly restrict drone flights by private companies and government agencies (though not by individual hobbyists). Even with an FAA permit, operators can’t fly UAVs above 400 feet or near airports or other zones with heavy air traffic, and they must maintain visual contact with the drones. All that may change, though, under the new law, which requires the FAA to allow the “safe integration” of UAVs into U.S. airspace.

If the FAA relaxes its rules, says Mark Brown, the civilian market for drones—and especially small, low-cost, tactical drones—could soon dwarf military sales, which in 2011 totaled more than three billion dollars. Brown, a former astronaut who is now an aerospace consultant in Dayton, Ohio, helps bring drone manufacturers and potential customers together. The success of military UAVs, he contends, has created “an appetite for more, more, more!” Brown’s PowerPoint presentation is called “On the Threshold of a Dream.”

Dreaming in Dayton

Drone fever is especially palpable in Dayton, cradle of American aviation, home of the Wright brothers and of Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. Even before the recent recession, Dayton was struggling. Over the past decade several large companies, including General Motors, have shut down operations here. But Dayton’s airport is lined with advertisements for aerospace companies; an ad for the Predator Mission Aircrew Training System shows two men in flight suits staring stoically at a battery of computer monitors. The city is dotted with drone entrepreneurs. “This is one of the few new industries with a chance to grow rapidly,” Brown says.

One of those entrepreneurs is Donald Smith, a bearish former Navy aircraft technician with ginger hair and a goatee. His firm, UA Vision, manufactures a delta-wing drone called the Spear. Made of polystyrene foam wrapped in woven carbon fiber or other fabrics, the Spear comes in several sizes; the smallest has a four-foot wingspan and weighs less than four pounds. It resembles a toy B-1 bomber. Smith sees it being used to keep track of pets, livestock, wildlife, even Alzheimer’s patients—anything or anyone equipped with radio-frequency identification tags that can be read remotely.

In the street outside the UA Vision factory a co-worker tosses the drone into the air, and Smith takes control of it with a handheld device. The drone swoops up and almost out of sight, plummets, corkscrews, loops the loop, skims a deserted lot across the street, arcs back up, and then slows down until it seems to hover, motionless, above us. Smith grins at me. “This plane is fully aerobatic,” he says.

A few miles away at Wright-Patterson stands the Air Force Institute of Technology, a center of military drone research. A bronze statue of a bedraggled winged man, Icarus, adorns the entrance—a symbol both of aviation daring and of catastrophic navigation error. In one of the labs John Raquet, a balding, bespectacled civilian, is designing new navigation systems for drones.

GPS is vulnerable, he explains. Its signals can be blocked by buildings or deliberately jammed. In December 2011, when a CIA drone crashed in Iran, authorities there claimed they had diverted it by hacking its GPS. Raquet’s team is working on a system that would allow a drone to also navigate visually, like a human pilot, using a camera paired with pattern-recognition software. The lab’s goal, Raquet repeatedly emphasizes, is “systems that you can trust.”

A drone equipped with his visual navigation system, Racquet says, might even recognize power lines and drain electricity from them with a “bat hook,” recharging its batteries on the fly. (This would be stealing, so Raquet would not recommend it for civilians.) He demonstrates the stunt for me with a square drone powered by rotors at each corner. On the first try the drone, buzzing like a nest of enraged hornets, flips over. On the second it crashes into a wall. “This demonstrates the need for trust,” Raquet says with a strained smile. Finally the quad-rotor wobbles into the air and drapes a hook over a cable slung across the room.

Down the hall from Raquet’s lab, Richard Cobb is trying to make drones that “hide in plain sight.” DARPA, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, has challenged researchers to build drones that mimic the size and behavior of bugs and birds. Cobb’s answer is a robotic hawk moth, with wings made of carbon fiber and Mylar. Piezoelectric motors flap the wings 30 times a second, so rapidly they vanish in a blur. Fashioning bug-size drones that can stay aloft for more than a few minutes, though, will require enormous advances in battery technology. Cobb expects it to take more than a decade.

The Air Force has nonetheless already constructed a “micro-aviary” at Wright-Patterson for flight-testing small drones. It’s a cavernous chamber—35 feet high and covering almost 4,000 square feet—with padded walls. Micro-aviary researchers, much of whose work is classified, decline to let me witness a flight test. But they do show me an animated video starring micro-UAVs that resemble winged, multi-legged bugs. The drones swarm through alleys, crawl across windowsills, and perch on power lines. One of them sneaks up on a scowling man holding a gun and shoots him in the head. The video concludes, “Unobtrusive, pervasive, lethal: micro air vehicles.”

What, one might ask, will prevent terrorists and criminals from getting their hands on some kind of lethal drone? Although American officials rarely discuss the threat in public, they take it seriously. The militant Islamic group Hezbollah, based in Lebanon, says it has obtained drones from Iran. Last November a federal court sentenced a Massachusetts man to 17 years in prison for plotting to attack Washington, D.C., with drones loaded with C-4 explosives.

Exercises carried out by security agencies suggest that defending against small drones would be difficult. Under a program called Black Dart, a mini-drone two feet long tested defenses at a military range. A video from its onboard camera shows a puff of smoke in the distance, from which emerges a tiny *** that rapidly grows larger before whizzing harmlessly past: That was a surface-to-air missile missing its mark. In a second video an F-16 fighter plane races past the drone without spotting it.

The answer to the threat of drone attacks, some engineers say, is more drones. “The new field is counter-UAVs,” says Stephen Griffiths, an engineer for the Utah-based avionics firm Procerus Technologies. Artificial-vision systems designed by Procerus would enable one UAV to spot and destroy another, either by ramming it or shooting it down. “If you can dream it,” Griffiths says, “you can do it.” Eventually drones may become smart enough to operate autonomously, with minimal human supervision. But Griffiths believes the ultimate decision to attack will remain with humans.

Another Man’s Nightmare

Even when controlled by skilled, well-intentioned operators, drones can pose a hazard—that’s what the FAA is concerned about. The safety record of military drones is not reassuring. Since 2001, according to the Air Force, its three main UAVs—the Predator, Global Hawk, and Reaper—have been involved in at least 120 “mishaps,” 76 of which destroyed the drone. The statistics don’t include drones operated by the other branches of the military or the CIA. Nor do they include drone attacks that accidentally killed civilians or U.S. or allied troops.

Even some proponents insist that drones must become much more reliable before they’re ready for widespread deployment in U.S. airspace. “No one should begrudge the FAA its mission of assuring safety, even if it adds significant costs to UAVs,” says Richard Scudder, who runs a University of Dayton laboratory that tests prototypes. One serious accident, Scudder points out, such as a drone striking a child playing in her backyard, could set the industry back years. “If we screw the pooch with this technology now,” he says, “it’s going to be a real mess.”

A drone crashing into a backyard would be messy; a drone crashing into a commercial airliner could be much worse. In Dayton the firm Defense Research Associates (DRA) is working on a “sense and avoid” system that would be cheaper and more compact than radar, says DRA project manager Andrew White. The principle is simple: A camera detects an object that’s rapidly growing larger and sends a signal to the autopilot, which swerves the UAV out of harm’s way. The DRA device, White suggests, could prevent collisions like the one that occurred in 2011 in Afghanistan, when a 400-pound Shadow drone smashed into a C-130 Hercules transport plane. The C-130 managed to land safely with the drone poking out of its wing.

The prospect of American skies swarming with drones raises more than just safety concerns. It alarms privacy advocates as well. Infrared and radio-band sensors used by the military can peer through clouds and foliage and can even—more than one source tells me—detect people inside buildings. Commercially available sensors too are extraordinarily sensitive. In Colorado, Chris Miser detaches the infrared camera from the Falcon, points it at me, and asks me to place my hand on my chest for just a moment. Several seconds later the live image from the camera still registers the heat of my handprint on my T-shirt.

During the last few years of the U.S. occupation of Iraq, unmanned aircraft monitored Baghdad 24/7, turning the entire city into the equivalent of a convenience store crammed with security cameras. After a roadside bombing U.S. officials could run videos in reverse to track bombers back to their hideouts. This practice is called persistent surveillance. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) worries that as drones become cheaper and more reliable, law enforcement agencies may be tempted to carry out persistent surveillance of U.S. citizens. The Fourth Amendment to the Constitution protects Americans from “unreasonable searches and seizures,” but it’s not clear how courts will apply that to drones.

What Jay Stanley of the ACLU calls his “nightmare scenario” begins with drones supporting “mostly unobjectionable” police raids and chases. Soon, however, networks of linked drones and computers “gain the ability to automatically track multiple vehicles and bodies as they move around a city,” much as the cell phone network hands calls from one tower to the next. The nightmare climaxes with authorities combining drone video and cell phone tracking to build up databases of people’s routine comings and goings—databases they can then mine for suspicious behavior. Stanley’s nightmare doesn’t even include the possibility that police drones might be armed.

Who’s Driving?

The invention that escapes our control, proliferating whether or not it benefits humanity, has been a persistent fear of the industrial age—with good reason. Nuclear weapons are too easy an example; consider what cars have done to our landscape over the past century, and it’s fair to wonder who’s in the driver’s seat, them or us. Most people would say cars have, on the whole, benefited humanity. A century from now there may be the same agreement about drones, if we take steps early on to control the risks.

At the Mesa County sheriff ’s office Benjamin Miller says he has no interest in armed drones. “I want to save lives, not take lives,” he says. Chris Miser expresses the same sentiment. When he was in the Air Force, he helped maintain and design lethal drones, including the Switchblade, which fits in a backpack and carries a grenade-size explosive. For the Falcon, Miser envisions lifesaving missions. He pictures it finding, say, a child who has wandered away from a campground. Successes like that, he says, would prove the Falcon’s value. They would help him “feel a lot better about what I’m doing.”

(Unmanned Flight: The Drones Come Home - Pictures, More From National Geographic Magazine)

The Drones Come Home

Unmanned aircraft have proved their prowess against al Qaeda. Now they’re poised to take off on the home front. Possible missions: patrolling borders, tracking perps, dusting crops. And maybe watching us all?

By John Horgan

Photograph by Joe McNally

At the edge of a stubbly, dried-out alfalfa field outside Grand Junction, Colorado, Deputy Sheriff Derek Johnson, a stocky young man with a buzz cut, squints at a speck crawling across the brilliant, hazy sky. It’s not a vulture or crow but a Falcon—a new brand of unmanned aerial vehicle, or drone, and Johnson is flying it. The sheriff ’s office here in Mesa County, a plateau of farms and ranches corralled by bone-hued mountains, is weighing the Falcon’s potential for spotting lost hikers and criminals on the lam. A laptop on a table in front of Johnson shows the drone’s flickering images of a nearby highway.

Standing behind Johnson, watching him watch the Falcon, is its designer, Chris Miser. Rock-jawed, arms crossed, sunglasses pushed atop his shaved head, Miser is a former Air Force captain who worked on military drones before quitting in 2007 to found his own company in Aurora, Colorado. The Falcon has an eight-foot wingspan but weighs just 9.5 pounds. Powered by an electric motor, it carries two swiveling cameras, visible and infrared, and a GPS-guided autopilot. Sophisticated enough that it can’t be exported without a U.S. government license, the Falcon is roughly comparable, Miser says, to the Raven, a hand-launched military drone—but much cheaper. He plans to sell two drones and support equipment for about the price of a squad car.

A law signed by President Barack Obama in February 2012 directs the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to throw American airspace wide open to drones by September 30, 2015. But for now Mesa County, with its empty skies, is one of only a few jurisdictions with an FAA permit to fly one. The sheriff ’s office has a three-foot-wide helicopter drone called a Draganflyer, which stays aloft for just 20 minutes.

The Falcon can fly for an hour, and it’s easy to operate. “You just put in the coordinates, and it flies itself,” says Benjamin Miller, who manages the unmanned aircraft program for the sheriff ’s office. To navigate, Johnson types the desired altitude and airspeed into the laptop and clicks targets on a digital map; the autopilot does the rest. To launch the Falcon, you simply hurl it into the air. An accelerometer switches on the propeller only after the bird has taken flight, so it won’t slice the hand that launches it.

The stench from a nearby chicken-processing plant wafts over the alfalfa field. “Let’s go ahead and tell it to land,” Miser says to Johnson. After the deputy sheriff clicks on the laptop, the Falcon swoops lower, releases a neon orange parachute, and drifts gently to the ground, just yards from the spot Johnson clicked on. “The Raven can’t do that,” Miser says proudly.

Offspring of 9/11

A dozen years ago only two communities cared much about drones. One was hobbyists who flew radio-controlled planes and choppers for fun. The other was the military, which carried out surveillance missions with unmanned aircraft like the General Atomics Predator.

Then came 9/11, followed by the U.S. invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, and drones rapidly became an essential tool of the U.S. armed forces. The Pentagon armed the Predator and a larger unmanned surveillance plane, the Reaper, with missiles, so that their operators—sitting in offices in places like Nevada or New York—could destroy as well as spy on targets thousands of miles away. Aerospace firms churned out a host of smaller drones with increasingly clever computer chips and keen sensors—cameras but also instruments that measure airborne chemicals, pathogens, radioactive materials.

The U.S. has deployed more than 11,000 military drones, up from fewer than 200 in 2002. They carry out a wide variety of missions while saving money and American lives. Within a generation they could replace most manned military aircraft, says John Pike, a defense expert at the think tank GlobalSecurity.org. Pike suspects that the F-35 Lightning II, now under development by Lockheed Martin, might be “the last fighter with an ejector seat, and might get converted into a drone itself.”

At least 50 other countries have drones, and some, notably China, Israel, and Iran, have their own manufacturers. Aviation firms—as well as university and government researchers—are designing a flock of next-generation aircraft, ranging in size from robotic moths and hummingbirds to Boeing’s Phantom Eye, a hydrogen-fueled behemoth with a 150-foot wingspan that can cruise at 65,000 feet for up to four days.

More than a thousand companies, from tiny start-ups like Miser’s to major defense contractors, are now in the drone business—and some are trying to steer drones into the civilian world. Predators already help Customs and Border Protection agents spot smugglers and illegal immigrants sneaking into the U.S. NASA-operated Global Hawks record atmospheric data and peer into hurricanes. Drones have helped scientists gather data on volcanoes in Costa Rica, archaeological sites in Russia and Peru, and flooding in North Dakota.

So far only a dozen police departments, including ones in Miami and Seattle, have applied to the FAA for permits to fly drones. But drone advocates—who generally prefer the term UAV, for unmanned aerial vehicle—say all 18,000 law enforcement agencies in the U.S. are potential customers. They hope UAVs will soon become essential too for agriculture (checking and spraying crops, finding lost cattle), journalism (scoping out public events or celebrity backyards), weather forecasting, traffic control. “The sky’s the limit, pun intended,” says Bill Borgia, an engineer at Lockheed Martin. “Once we get UAVs in the hands of potential users, they’ll think of lots of cool applications.”

The biggest obstacle, advocates say, is current FAA rules, which tightly restrict drone flights by private companies and government agencies (though not by individual hobbyists). Even with an FAA permit, operators can’t fly UAVs above 400 feet or near airports or other zones with heavy air traffic, and they must maintain visual contact with the drones. All that may change, though, under the new law, which requires the FAA to allow the “safe integration” of UAVs into U.S. airspace.

If the FAA relaxes its rules, says Mark Brown, the civilian market for drones—and especially small, low-cost, tactical drones—could soon dwarf military sales, which in 2011 totaled more than three billion dollars. Brown, a former astronaut who is now an aerospace consultant in Dayton, Ohio, helps bring drone manufacturers and potential customers together. The success of military UAVs, he contends, has created “an appetite for more, more, more!” Brown’s PowerPoint presentation is called “On the Threshold of a Dream.”

Dreaming in Dayton

Drone fever is especially palpable in Dayton, cradle of American aviation, home of the Wright brothers and of Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. Even before the recent recession, Dayton was struggling. Over the past decade several large companies, including General Motors, have shut down operations here. But Dayton’s airport is lined with advertisements for aerospace companies; an ad for the Predator Mission Aircrew Training System shows two men in flight suits staring stoically at a battery of computer monitors. The city is dotted with drone entrepreneurs. “This is one of the few new industries with a chance to grow rapidly,” Brown says.

One of those entrepreneurs is Donald Smith, a bearish former Navy aircraft technician with ginger hair and a goatee. His firm, UA Vision, manufactures a delta-wing drone called the Spear. Made of polystyrene foam wrapped in woven carbon fiber or other fabrics, the Spear comes in several sizes; the smallest has a four-foot wingspan and weighs less than four pounds. It resembles a toy B-1 bomber. Smith sees it being used to keep track of pets, livestock, wildlife, even Alzheimer’s patients—anything or anyone equipped with radio-frequency identification tags that can be read remotely.

In the street outside the UA Vision factory a co-worker tosses the drone into the air, and Smith takes control of it with a handheld device. The drone swoops up and almost out of sight, plummets, corkscrews, loops the loop, skims a deserted lot across the street, arcs back up, and then slows down until it seems to hover, motionless, above us. Smith grins at me. “This plane is fully aerobatic,” he says.

A few miles away at Wright-Patterson stands the Air Force Institute of Technology, a center of military drone research. A bronze statue of a bedraggled winged man, Icarus, adorns the entrance—a symbol both of aviation daring and of catastrophic navigation error. In one of the labs John Raquet, a balding, bespectacled civilian, is designing new navigation systems for drones.

GPS is vulnerable, he explains. Its signals can be blocked by buildings or deliberately jammed. In December 2011, when a CIA drone crashed in Iran, authorities there claimed they had diverted it by hacking its GPS. Raquet’s team is working on a system that would allow a drone to also navigate visually, like a human pilot, using a camera paired with pattern-recognition software. The lab’s goal, Raquet repeatedly emphasizes, is “systems that you can trust.”

A drone equipped with his visual navigation system, Racquet says, might even recognize power lines and drain electricity from them with a “bat hook,” recharging its batteries on the fly. (This would be stealing, so Raquet would not recommend it for civilians.) He demonstrates the stunt for me with a square drone powered by rotors at each corner. On the first try the drone, buzzing like a nest of enraged hornets, flips over. On the second it crashes into a wall. “This demonstrates the need for trust,” Raquet says with a strained smile. Finally the quad-rotor wobbles into the air and drapes a hook over a cable slung across the room.

Down the hall from Raquet’s lab, Richard Cobb is trying to make drones that “hide in plain sight.” DARPA, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, has challenged researchers to build drones that mimic the size and behavior of bugs and birds. Cobb’s answer is a robotic hawk moth, with wings made of carbon fiber and Mylar. Piezoelectric motors flap the wings 30 times a second, so rapidly they vanish in a blur. Fashioning bug-size drones that can stay aloft for more than a few minutes, though, will require enormous advances in battery technology. Cobb expects it to take more than a decade.

The Air Force has nonetheless already constructed a “micro-aviary” at Wright-Patterson for flight-testing small drones. It’s a cavernous chamber—35 feet high and covering almost 4,000 square feet—with padded walls. Micro-aviary researchers, much of whose work is classified, decline to let me witness a flight test. But they do show me an animated video starring micro-UAVs that resemble winged, multi-legged bugs. The drones swarm through alleys, crawl across windowsills, and perch on power lines. One of them sneaks up on a scowling man holding a gun and shoots him in the head. The video concludes, “Unobtrusive, pervasive, lethal: micro air vehicles.”

What, one might ask, will prevent terrorists and criminals from getting their hands on some kind of lethal drone? Although American officials rarely discuss the threat in public, they take it seriously. The militant Islamic group Hezbollah, based in Lebanon, says it has obtained drones from Iran. Last November a federal court sentenced a Massachusetts man to 17 years in prison for plotting to attack Washington, D.C., with drones loaded with C-4 explosives.

Exercises carried out by security agencies suggest that defending against small drones would be difficult. Under a program called Black Dart, a mini-drone two feet long tested defenses at a military range. A video from its onboard camera shows a puff of smoke in the distance, from which emerges a tiny *** that rapidly grows larger before whizzing harmlessly past: That was a surface-to-air missile missing its mark. In a second video an F-16 fighter plane races past the drone without spotting it.

The answer to the threat of drone attacks, some engineers say, is more drones. “The new field is counter-UAVs,” says Stephen Griffiths, an engineer for the Utah-based avionics firm Procerus Technologies. Artificial-vision systems designed by Procerus would enable one UAV to spot and destroy another, either by ramming it or shooting it down. “If you can dream it,” Griffiths says, “you can do it.” Eventually drones may become smart enough to operate autonomously, with minimal human supervision. But Griffiths believes the ultimate decision to attack will remain with humans.

Another Man’s Nightmare

Even when controlled by skilled, well-intentioned operators, drones can pose a hazard—that’s what the FAA is concerned about. The safety record of military drones is not reassuring. Since 2001, according to the Air Force, its three main UAVs—the Predator, Global Hawk, and Reaper—have been involved in at least 120 “mishaps,” 76 of which destroyed the drone. The statistics don’t include drones operated by the other branches of the military or the CIA. Nor do they include drone attacks that accidentally killed civilians or U.S. or allied troops.

Even some proponents insist that drones must become much more reliable before they’re ready for widespread deployment in U.S. airspace. “No one should begrudge the FAA its mission of assuring safety, even if it adds significant costs to UAVs,” says Richard Scudder, who runs a University of Dayton laboratory that tests prototypes. One serious accident, Scudder points out, such as a drone striking a child playing in her backyard, could set the industry back years. “If we screw the pooch with this technology now,” he says, “it’s going to be a real mess.”

A drone crashing into a backyard would be messy; a drone crashing into a commercial airliner could be much worse. In Dayton the firm Defense Research Associates (DRA) is working on a “sense and avoid” system that would be cheaper and more compact than radar, says DRA project manager Andrew White. The principle is simple: A camera detects an object that’s rapidly growing larger and sends a signal to the autopilot, which swerves the UAV out of harm’s way. The DRA device, White suggests, could prevent collisions like the one that occurred in 2011 in Afghanistan, when a 400-pound Shadow drone smashed into a C-130 Hercules transport plane. The C-130 managed to land safely with the drone poking out of its wing.

The prospect of American skies swarming with drones raises more than just safety concerns. It alarms privacy advocates as well. Infrared and radio-band sensors used by the military can peer through clouds and foliage and can even—more than one source tells me—detect people inside buildings. Commercially available sensors too are extraordinarily sensitive. In Colorado, Chris Miser detaches the infrared camera from the Falcon, points it at me, and asks me to place my hand on my chest for just a moment. Several seconds later the live image from the camera still registers the heat of my handprint on my T-shirt.

During the last few years of the U.S. occupation of Iraq, unmanned aircraft monitored Baghdad 24/7, turning the entire city into the equivalent of a convenience store crammed with security cameras. After a roadside bombing U.S. officials could run videos in reverse to track bombers back to their hideouts. This practice is called persistent surveillance. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) worries that as drones become cheaper and more reliable, law enforcement agencies may be tempted to carry out persistent surveillance of U.S. citizens. The Fourth Amendment to the Constitution protects Americans from “unreasonable searches and seizures,” but it’s not clear how courts will apply that to drones.

What Jay Stanley of the ACLU calls his “nightmare scenario” begins with drones supporting “mostly unobjectionable” police raids and chases. Soon, however, networks of linked drones and computers “gain the ability to automatically track multiple vehicles and bodies as they move around a city,” much as the cell phone network hands calls from one tower to the next. The nightmare climaxes with authorities combining drone video and cell phone tracking to build up databases of people’s routine comings and goings—databases they can then mine for suspicious behavior. Stanley’s nightmare doesn’t even include the possibility that police drones might be armed.

Who’s Driving?

The invention that escapes our control, proliferating whether or not it benefits humanity, has been a persistent fear of the industrial age—with good reason. Nuclear weapons are too easy an example; consider what cars have done to our landscape over the past century, and it’s fair to wonder who’s in the driver’s seat, them or us. Most people would say cars have, on the whole, benefited humanity. A century from now there may be the same agreement about drones, if we take steps early on to control the risks.

At the Mesa County sheriff ’s office Benjamin Miller says he has no interest in armed drones. “I want to save lives, not take lives,” he says. Chris Miser expresses the same sentiment. When he was in the Air Force, he helped maintain and design lethal drones, including the Switchblade, which fits in a backpack and carries a grenade-size explosive. For the Falcon, Miser envisions lifesaving missions. He pictures it finding, say, a child who has wandered away from a campground. Successes like that, he says, would prove the Falcon’s value. They would help him “feel a lot better about what I’m doing.”

(Unmanned Flight: The Drones Come Home - Pictures, More From National Geographic Magazine)

Ir.Tab.

FULL MEMBER

- Joined

- Apr 15, 2012

- Messages

- 1,170

- Reaction score

- 0

Boeing’s liquid hydrogen-powered Phantom Eye Completes 2nd Flight

Boeing Phantom Eye Completes 2nd Flight | UAS VISION

The Phantom Eye demonstrator is designed to be capable of carrying a 450-pound payload while operating for up to four days at altitudes of up to 65,000 feet.

Boeing Phantom Eye Completes 2nd Flight | UAS VISION

The Phantom Eye demonstrator is designed to be capable of carrying a 450-pound payload while operating for up to four days at altitudes of up to 65,000 feet.

Ir.Tab.

FULL MEMBER

- Joined

- Apr 15, 2012

- Messages

- 1,170

- Reaction score

- 0

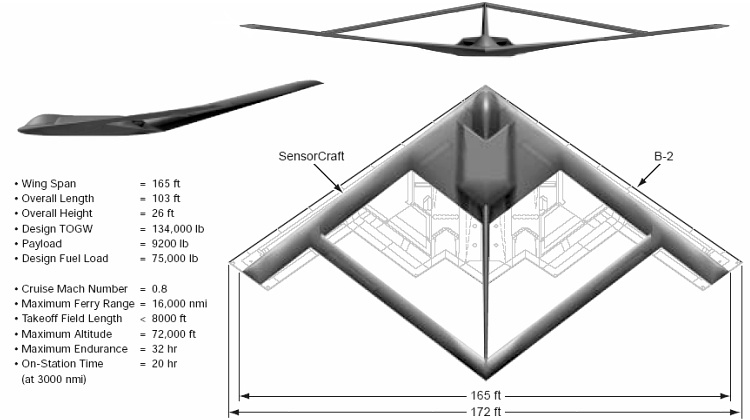

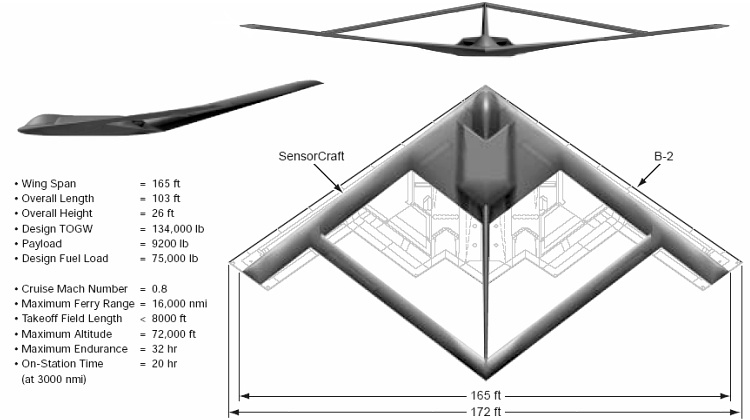

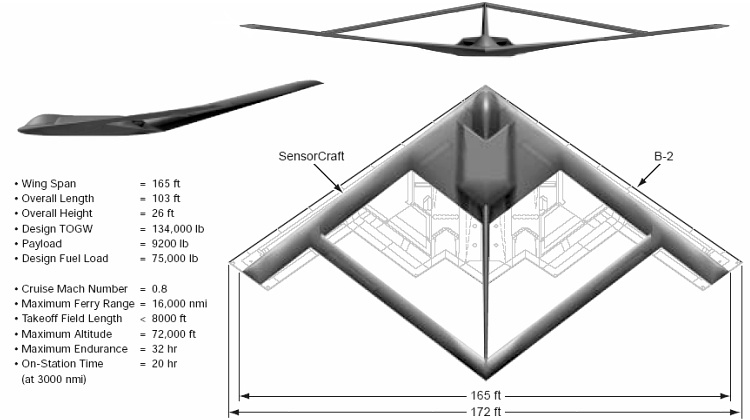

The Boeing Sensor-craft.

Yes it exists!

http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a470037.pdf

If you guys want a very long, long, long read (to the second power) read here: http://www.hitechweb.genezis.eu/UAV02.htm

Translate from solvak and get "readin"

Yes it exists!

http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a470037.pdf

If you guys want a very long, long, long read (to the second power) read here: http://www.hitechweb.genezis.eu/UAV02.htm

Translate from solvak and get "readin"

SOHEIL

ELITE MEMBER

- Joined

- Dec 9, 2011

- Messages

- 15,796

- Reaction score

- -6

- Country

- Location

The Boeing Sensor-craft.

Yes it exists!

http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a470037.pdf

If you guys want a very long, long, long read (to the second power) read here: Tajn americk bezpilotn prieskumn lietadl kategrie stealth

Translate from solvak and get "readin"

exists!

Nishan_101

BANNED

- Joined

- Nov 23, 2007

- Messages

- 3,825

- Reaction score

- -18

SELEX Galileo Falco

The Falco (English: hawk) is a tactical unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) designed and produced by SELEX Galileo (originally by Galileo Avionica) of Italy. The UAV is designed to be a medium-altitude, medium-endurance surveillance platform capable of carrying a range of payloads, including several types of high resolution sensors. It's payload does not include weapons, however. The launch customer, Pakistan, reportedly wanted the Falco armed, a request that Italy rejected.A larger variant, capable of carrying larger payloads and designated Falco Evo, is in development. The Falco UAV is not capable of deploying weapons such as guided missiles and bombs, but the Falco Evo is expected to do so.

Specifications :

General characteristics

Payload: 70 kg (154 lb)

Length: 5.25 m (17.2 ft)

Wingspan: 7.2 m (23.6 ft)

Height: 1.8 m (5.9 ft)

Max. takeoff weight: 420 kg (926 lb)

Powerplant: 1 × Petrol, 65 hp (48 kW)

Performance

Maximum speed: 216 km/h (134 mph)

Service ceiling: 6,500 m (21,325 ft)

Armament

Hardpoints: 2× under-wing with a capacity of 70 kg

Avionics

Communications: Jamming-resistant data-link, real time data transmission, range >200 km

Mission payloads:

High resolution cameras: thermal imaging, hyperspectral imaging, colour TV, EO [8]

Radars: Synthetic aperture radar, maritime surveillance radar

Targeting: Laser designator

Others: Electronic support measures equipment, NBC sensors, self-protection equipment (chaff / flare dispensers)

More : Falco_UAV

Why can't we put the technology on a bigger UAV which we can design & develop at PAC.

cabatli_53

ELITE MEMBER

- Joined

- Feb 20, 2008

- Messages

- 12,808

- Reaction score

- 62

- Country

- Location

Take a look that beauty... My God !!!

Last edited by a moderator:

Nah, I was talking about the design, not in service.exists!

Manticore

RETIRED MOD

- Joined

- Jan 18, 2009

- Messages

- 10,115

- Reaction score

- 114

- Country

- Location

Navy’s High-Flying Spy Drone Completes Its First Flight

The MQ-4C Triton took off today for the first time from a Palmdale, California airfield, a major step in the Navy’s Broad Area Maritime Surveillance program. Northrop Grumman, which manufactured the 130.9-foot-wingspan drone, said the maiden voyage lasted an hour and a half. The Navy even announced it via Twitter.

“First flight represents a critical step in maturing Triton’s systems before operationally supporting the Navy’s maritime surveillance mission around the world,” Capt. James Hoke, Triton’s program manager, said in a statement.

If the Triton looks familiar, it should. It’s a souped-up version of the Air Force’s old reliable spy drone, Northrop Grumman’s Global Hawk. The Navy’s made some modifications to the airframe and the sensors it carries to ensure it can spy on vast swaths of ocean, from great height. (It’s unarmed, if you were wondering.)

The idea is for the Triton to achieve altitudes of nearly 53,000 feet — that’s 10 miles up — where it will scan 2,000 nautical miles at a single robotic blink. (Notice that wingspan is bigger than a 737's.) Its sensors, Northrop boasts, will “detect and automatically classify” ships, giving captains a much broader view of what’s on the water than radar, sonar and manned aircraft provide. Not only that, Triton is a flying communications relay station, bouncing “airborne communications and information sharing capabilities” between ships. And it can fly about 11,500 miles without refueling.

The MQ-4C Triton took off today for the first time from a Palmdale, California airfield, a major step in the Navy’s Broad Area Maritime Surveillance program. Northrop Grumman, which manufactured the 130.9-foot-wingspan drone, said the maiden voyage lasted an hour and a half. The Navy even announced it via Twitter.

“First flight represents a critical step in maturing Triton’s systems before operationally supporting the Navy’s maritime surveillance mission around the world,” Capt. James Hoke, Triton’s program manager, said in a statement.

If the Triton looks familiar, it should. It’s a souped-up version of the Air Force’s old reliable spy drone, Northrop Grumman’s Global Hawk. The Navy’s made some modifications to the airframe and the sensors it carries to ensure it can spy on vast swaths of ocean, from great height. (It’s unarmed, if you were wondering.)

The idea is for the Triton to achieve altitudes of nearly 53,000 feet — that’s 10 miles up — where it will scan 2,000 nautical miles at a single robotic blink. (Notice that wingspan is bigger than a 737's.) Its sensors, Northrop boasts, will “detect and automatically classify” ships, giving captains a much broader view of what’s on the water than radar, sonar and manned aircraft provide. Not only that, Triton is a flying communications relay station, bouncing “airborne communications and information sharing capabilities” between ships. And it can fly about 11,500 miles without refueling.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 3K

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 496

- Article

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 737

- Article

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 519