RisingShiningSuperpower

BANNED

- Joined

- Jun 12, 2014

- Messages

- 1,446

- Reaction score

- -6

- Country

- Location

I'm confident the answer is a resounding affirmative. India has the brains and the money to achieve anything, only leadership was lacking before. With Modi-ji in power, India will quickly move ahead in all areas, including bullet trains.

Can Modi Build India's Bullet Train? - Forbes

Can Modi Build India's Bullet Train? - Forbes

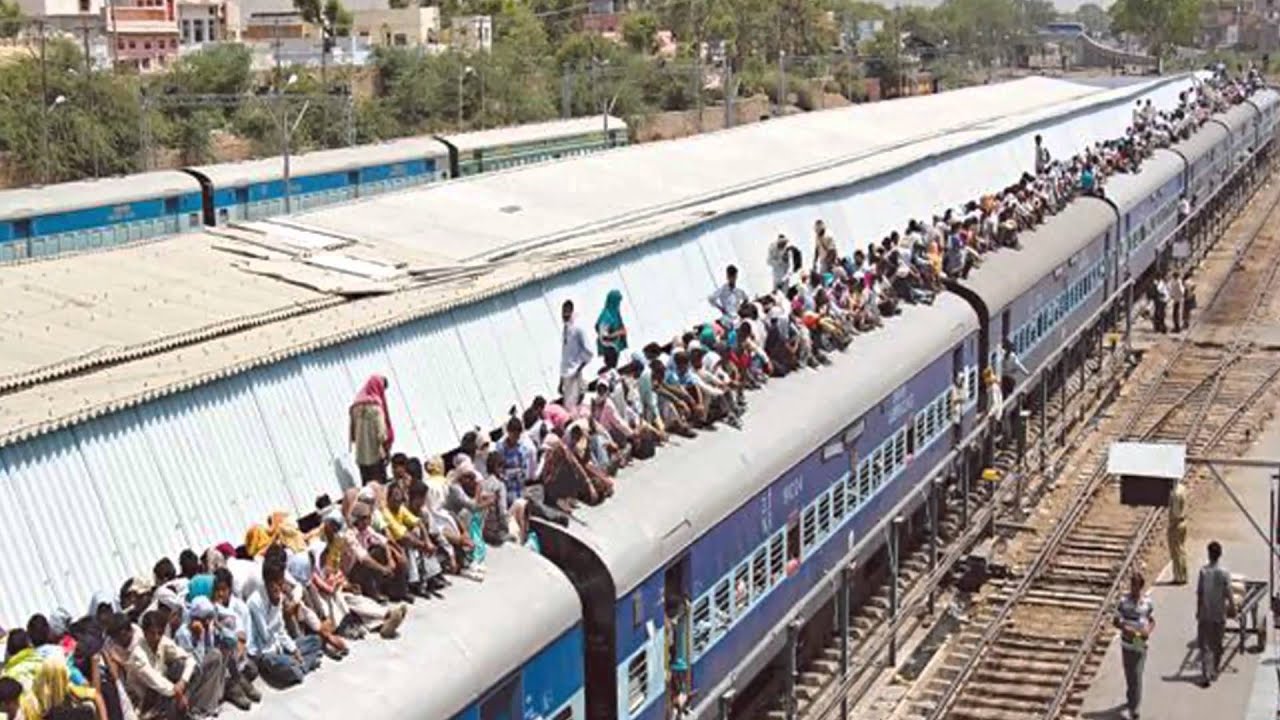

Let’s call a spade a spade here, shall we? This crazy train is ridiculous. If India wants to modernize, it has to build 21st century infrastructure for the 20 million people that ride banana slugs on a daily basis.

India is the world’s largest democracy. And as everyone living in a democracy knows, ruling by consensus is about give and take. In a country of 1.2 billion people, that give and take is a tug of war that goes on and on and on without end. In theory, that tug of war ended with the mandate given to new prime minister Narendra Modi last May. Now, Modi has to deliver on his proposals to turn India into a 21st century economy.

“India’s challenge has always been execution,” Oppenheimer’s CIO Krishna Memani tells FORBES. He knows India well. With a name like Krishna, it would be disappointing if he didn’t. “In the current go-round, it is probably the luckiest country in the world because it got a political mandate to change its policies in a material way and it got the tailwind of a lower commodity environment.”

Cheaper commodities are important for India. It’s a big importer of oil and gold. These two commodities tend to lead to deficits.

“India has all the things in place for executing on those policies set forth by Modi in his new budget,” says Memani. “But the fact that Modi has a political mandate doesn’t make it any easier to get things to pass parliament.”

The opposition is far from dead, even though the BJP party delivered a knock-out punch to the Indian National Congress last year. Bleeding heart liberals aren’t big Modi fans because they see him as too pro-business, which apparently means he is anti-poor. He is also a Hindu nationalist. And in a country as big as India, states are like mini-colonies within the whole. This is not a dictatorship Modi is running. It’s not China. There will be no bullet trains anytime soon. Indians will still be hopping on the crazy train instead. But if politicians care about the future of the country, its first things first: you have to develop the infrastructure so little children aren’t walking two miles to school every day. You have to build water treatment facilities so you can grow up from a country where the poor making a living cleaning excrement out of slightly-less-poor people’s houses.

Drive along any road in India and its a wonder you don’t see more cars turned over. There’s a moped that just got hit by an auto-rickshaw. No helmet. No shoes. He’s up and driving his little white bike in no time in the mixed religions city of Hyderabad. There’s the colorful delivery trucks. They have no mirrors. They chug up tight, one lane roads. For the feint of heart, driving from Ranchi to the steel mill town of Jamshedpur is a bit like being on the Batman ride at Six Flags amusement park.

It has been over 10 years since the last time the BJP led the government. Back then, they launched the so-called Golden Quadrilateral (GQ) project to improve connectivity among four major Indian cities on the four corners of the country: New Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai and Kolkata. Back then, BJP did not have a majority in the parliament.

The Congress-led government declared in 2012 that work was complete on a 5,846 kilometer stretch in the GQ, which included building, widening and resurfacing the roads already in existence. As of this year, however, there are still at least three vehicle overpasses under construction or not operational, adding to gridlock.

Since taking office, Modi’s government has taken steps to get road projects moving. According to a December 2014 report by Standard & Poor’s, work has started on 75% of the 16 projects that the previous government bid out in 2014 compared with work that had begun on just 10% of the projects in 2012 and 18% in 2013.

Modi is a man of action. But he has no choice, really.

In the past five years, 90% of the national highway projects that were completed had been delayed by lack of environmental clearances, nonavailability of land and funding constraints, among other issues. Modi’s government has tried to overcome many of these blockages by easing environmental and land acquisition regulations, but many of its ordinances are still subject to parliamentary approval. They will likely be held up by the opposition which see the current Land Bill as farm land thievery.

Modi’s many announcements since coming to power in May 2014 have included pledges to improve India’s rickety physical infrastructure, too, which includes transportation and utilities.

Soon after being elected, he promised electricity for every home in India over the next five years and road construction of 25 kilometers a day increasing to 30 kilometers a day by 2016.

On the execution side of the equation, prior to Modi — between April 2014 and October 2014, some 705 kilometers of highway were completed under the orders of the previous government. Modi was in power in May, but those work orders were ongoing. They were down by 23% from the same period in the previous year, according to NHAI data. This translates into a daily rate of just three kilometers of new roads being built or re-asphalted, which is worse than the four kilometers a day in 2013.

Like Modi, the Roads Minister under the previous government had a road construction target of 20 kilometers a day.

“Modi’s track record on meeting targets is not perfect,” says Shumita Sharma Deveshwar, an analyst at Trusted Sources in Mumbai.

According to a Jan. 12 article in the Mint newspaper, some $681 billion worth of Memorandums of Understanding were signed between investors and the Gujarat government between 2003 and 2011. Modi was the state’s head honcho then.

Only 10% of that amount was actually invested, and the report said that the government thereafter stopped disclosing the investment amount, declaring only the MoUs.

Execution.

No more crazy trains.

“The most important thing to monitor over the coming months is whether or not Modi and his government have the capability to implement what they have envisaged,” says Deveshwar. “The jury is still out.”

Can Modi Build India's Bullet Train? - Forbes

Can Modi Build India's Bullet Train? - Forbes

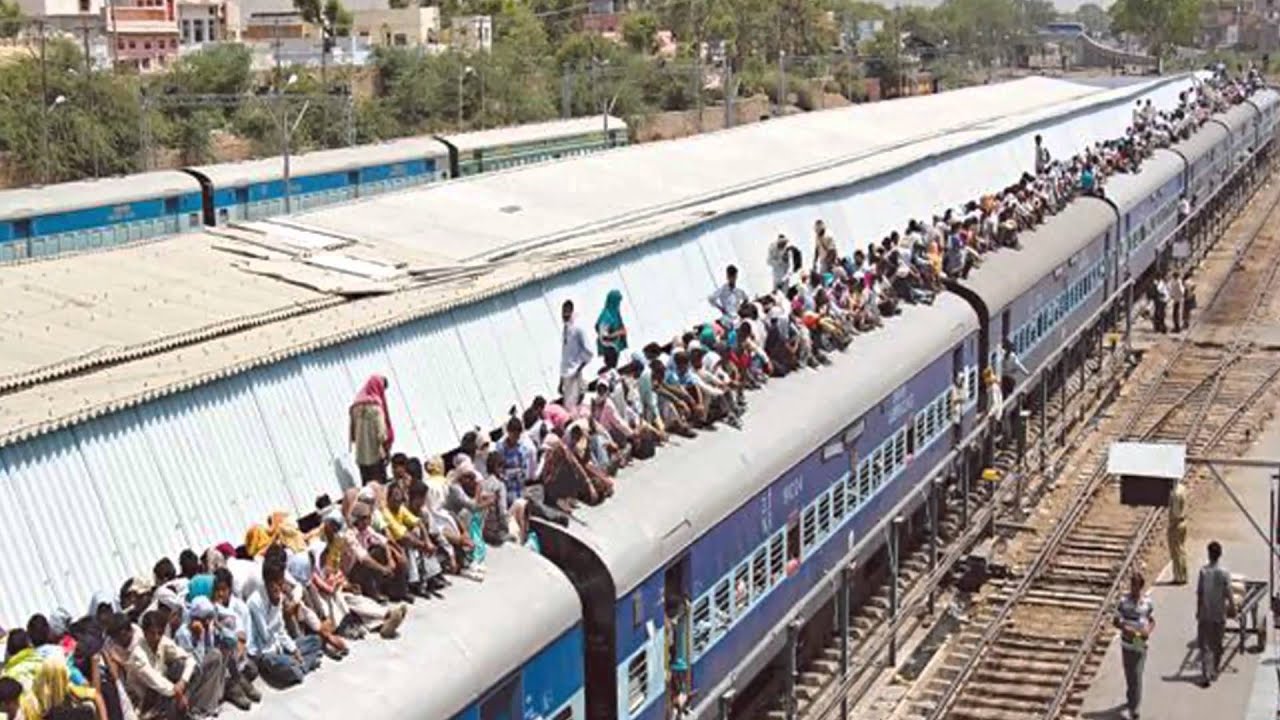

Let’s call a spade a spade here, shall we? This crazy train is ridiculous. If India wants to modernize, it has to build 21st century infrastructure for the 20 million people that ride banana slugs on a daily basis.

India is the world’s largest democracy. And as everyone living in a democracy knows, ruling by consensus is about give and take. In a country of 1.2 billion people, that give and take is a tug of war that goes on and on and on without end. In theory, that tug of war ended with the mandate given to new prime minister Narendra Modi last May. Now, Modi has to deliver on his proposals to turn India into a 21st century economy.

“India’s challenge has always been execution,” Oppenheimer’s CIO Krishna Memani tells FORBES. He knows India well. With a name like Krishna, it would be disappointing if he didn’t. “In the current go-round, it is probably the luckiest country in the world because it got a political mandate to change its policies in a material way and it got the tailwind of a lower commodity environment.”

Cheaper commodities are important for India. It’s a big importer of oil and gold. These two commodities tend to lead to deficits.

“India has all the things in place for executing on those policies set forth by Modi in his new budget,” says Memani. “But the fact that Modi has a political mandate doesn’t make it any easier to get things to pass parliament.”

The opposition is far from dead, even though the BJP party delivered a knock-out punch to the Indian National Congress last year. Bleeding heart liberals aren’t big Modi fans because they see him as too pro-business, which apparently means he is anti-poor. He is also a Hindu nationalist. And in a country as big as India, states are like mini-colonies within the whole. This is not a dictatorship Modi is running. It’s not China. There will be no bullet trains anytime soon. Indians will still be hopping on the crazy train instead. But if politicians care about the future of the country, its first things first: you have to develop the infrastructure so little children aren’t walking two miles to school every day. You have to build water treatment facilities so you can grow up from a country where the poor making a living cleaning excrement out of slightly-less-poor people’s houses.

Drive along any road in India and its a wonder you don’t see more cars turned over. There’s a moped that just got hit by an auto-rickshaw. No helmet. No shoes. He’s up and driving his little white bike in no time in the mixed religions city of Hyderabad. There’s the colorful delivery trucks. They have no mirrors. They chug up tight, one lane roads. For the feint of heart, driving from Ranchi to the steel mill town of Jamshedpur is a bit like being on the Batman ride at Six Flags amusement park.

It has been over 10 years since the last time the BJP led the government. Back then, they launched the so-called Golden Quadrilateral (GQ) project to improve connectivity among four major Indian cities on the four corners of the country: New Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai and Kolkata. Back then, BJP did not have a majority in the parliament.

The Congress-led government declared in 2012 that work was complete on a 5,846 kilometer stretch in the GQ, which included building, widening and resurfacing the roads already in existence. As of this year, however, there are still at least three vehicle overpasses under construction or not operational, adding to gridlock.

Since taking office, Modi’s government has taken steps to get road projects moving. According to a December 2014 report by Standard & Poor’s, work has started on 75% of the 16 projects that the previous government bid out in 2014 compared with work that had begun on just 10% of the projects in 2012 and 18% in 2013.

Modi is a man of action. But he has no choice, really.

In the past five years, 90% of the national highway projects that were completed had been delayed by lack of environmental clearances, nonavailability of land and funding constraints, among other issues. Modi’s government has tried to overcome many of these blockages by easing environmental and land acquisition regulations, but many of its ordinances are still subject to parliamentary approval. They will likely be held up by the opposition which see the current Land Bill as farm land thievery.

Modi’s many announcements since coming to power in May 2014 have included pledges to improve India’s rickety physical infrastructure, too, which includes transportation and utilities.

Soon after being elected, he promised electricity for every home in India over the next five years and road construction of 25 kilometers a day increasing to 30 kilometers a day by 2016.

On the execution side of the equation, prior to Modi — between April 2014 and October 2014, some 705 kilometers of highway were completed under the orders of the previous government. Modi was in power in May, but those work orders were ongoing. They were down by 23% from the same period in the previous year, according to NHAI data. This translates into a daily rate of just three kilometers of new roads being built or re-asphalted, which is worse than the four kilometers a day in 2013.

Like Modi, the Roads Minister under the previous government had a road construction target of 20 kilometers a day.

“Modi’s track record on meeting targets is not perfect,” says Shumita Sharma Deveshwar, an analyst at Trusted Sources in Mumbai.

According to a Jan. 12 article in the Mint newspaper, some $681 billion worth of Memorandums of Understanding were signed between investors and the Gujarat government between 2003 and 2011. Modi was the state’s head honcho then.

Only 10% of that amount was actually invested, and the report said that the government thereafter stopped disclosing the investment amount, declaring only the MoUs.

Execution.

No more crazy trains.

“The most important thing to monitor over the coming months is whether or not Modi and his government have the capability to implement what they have envisaged,” says Deveshwar. “The jury is still out.”

Last edited: