The SC

ELITE MEMBER

- Joined

- Feb 13, 2012

- Messages

- 32,233

- Reaction score

- 21

- Country

- Location

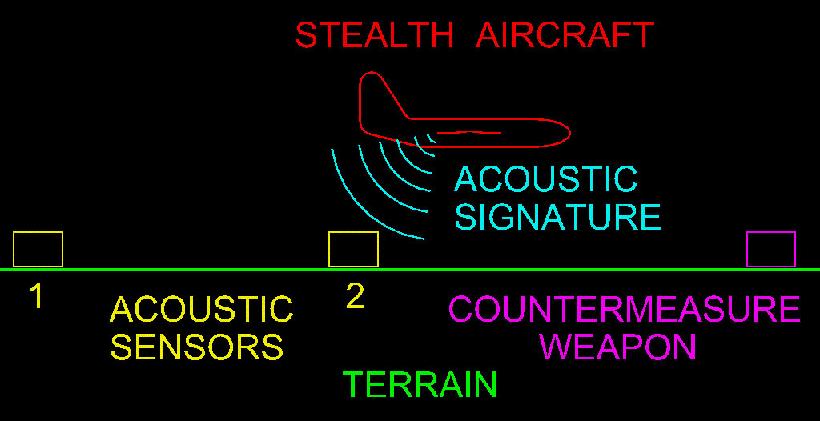

With sound technologies like 3D sound, directional sound and others, can stealth warplanes be identified? Do they have any particular sound to them? Or is the sound of their engines the same as other warplanes?

We know that Sound waves take approximately 5 seconds to travel 1 mile. Using this information, it is possible to measure one's distance from a lightning bolt.

Physics of sound

Sound can propagate through compressible media such as air, water and solids as longitudinal waves and also as a transverse waves in solids (see Longitudinal and transverse waves, below). The sound waves are generated by a sound source, such as the vibrating diaphragm of a stereo speaker. The sound source creates vibrations in the surrounding medium. As the source continues to vibrate the medium, the vibrations propagate away from the source at the speed of sound, thus forming the sound wave. At a fixed distance from the source, the pressure, velocity, and displacement of the medium vary in time. At an instant in time, the pressure, velocity, and displacement vary in space. Note that the particles of the medium do not travel with the sound wave. This is intuitively obvious for a solid, and the same is true for liquids and gases (that is, the vibrations of particles in the gas or liquid transport the vibrations, while the average position of the particles over time does not change). During propagation, waves can be reflected, refracted, or attenuated by the medium.[4]

The behavior of sound propagation is generally affected by three things:

When sound is moving through a medium that does not have constant physical properties, it may be refracted (either dispersed or focused).

Spherical compression (longitudinal) waves

The mechanical vibrations that can be interpreted as sound are able to travel through all forms of matter: gases, liquids, solids, and plasmas. The matter that supports the sound is called the medium. Sound cannot travel through a vacuum.

Longitudinal and transverse waves

Sound is transmitted through gases, plasma, and liquids as longitudinal waves, also called compression waves. Through solids, however, it can be transmitted as both longitudinal waves and transverse waves. Longitudinal sound waves are waves of alternating pressure deviations from the equilibrium pressure, causing local regions of compression and rarefaction, while transverse waves (in solids) are waves of alternating shear stress at right angle to the direction of propagation. Additionally, sound waves may be viewed simply by parabolic mirrors and objects that produce sound. [5]

The energy carried by an oscillating sound wave converts back and forth between the potential energy of the extra compression (in case of longitudinal waves) or lateral displacement strain (in case of transverse waves) of the matter, and the kinetic energy of the displacement velocity of particles of the medium.

Sound wave properties and characteristics

Sinusoidal waves of various frequencies; the bottom waves have higher frequencies than those above. The horizontal axis represents time.

Sound waves are often simplified to a description in terms of sinusoidal plane waves, which are characterized by these generic properties:

Sound that is perceptible by humans has frequencies from about 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz. In air at standard temperature and pressure, the corresponding wavelengths of sound waves range from 17 m to 17 mm. Sometimes speed and direction are combined as a velocity vector; wave number and direction are combined as a wave vector.

Transverse waves, also known as shear waves, have the additional property, polarization, and are not a characteristic of sound waves.

Speed of sound

U.S. Navy F/A-18 approaching the sound barrier. The white halo is formed by condensed water droplets thought to result from a drop in air pressure around the aircraft (see Prandtl-Glauert Singularity).

The speed of sound depends on the medium that the waves pass through, and is a fundamental property of the material. The first significant effort towards the measure of the speed of sound was made by Newton. He believed that the speed of sound in a particular substance was equal to the square root of the pressure acting on it (STP) divided by its density.

This was later proven wrong when found to incorrectly derive the speed. French mathematician Laplace corrected the formula by deducing that the phenomenon of sound traveling is not isothermal, as believed by Newton, but adiabatic. elastic modulus, c = velocity of sound, and

= density. Thus, the speed of sound is proportional to the square root of the ratio of the elastic modulus (stiffness) of the medium to its density.

= density. Thus, the speed of sound is proportional to the square root of the ratio of the elastic modulus (stiffness) of the medium to its density.

Those physical properties and the speed of sound change with ambient conditions. For example, the speed of sound in gases depends on temperature. In 20 °C (68 °F) air at sea level, the speed of sound is approximately 343 m/s (1,230 km/h; 767 mph) using the formula "v = (331 + 0.6 T) m/s". In fresh water, also at 20 °C, the speed of sound is approximately 1,482 m/s (5,335 km/h; 3,315 mph). In steel, the speed of sound is about 5,960 m/s (21,460 km/h; 13,330 mph). The speed of sound is also slightly sensitive (a second-order anharmonic effect) to the sound amplitude, which means that there are nonlinear propagation effects, such as the production of harmonics and mixed tones not present in the original sound (see parametric array).

Perception of sound

Human ear

A distinct use of the term sound from its use in physics is that in physiology and psychology, where the term refers to the subject of perception by the brain. The field of psychoacoustics is dedicated to such studies.

The physical reception of sound in any hearing organism is limited to a range of frequencies. Humans normally hear sound frequencies between approximately 20 Hz and 20,000 Hz (20 kHz),[9] Both limits, especially the upper limit, decrease with age.

Other species have a different range of hearing. For example, dogs can perceive vibrations higher than 20 kHz, but are deaf below 40 Hz. As a signal perceived by one of the major senses, sound is used by many species for detecting danger, navigation, predation, and communication. Earth's atmosphere, water, and virtually any physical phenomenon, such as fire, rain, wind, surf, or earthquake, produces (and is characterized by) its unique sounds.

Sound pressure is the difference, in a given medium, between average local pressure and the pressure in the sound wave. A square of this difference (i.e., a square of the deviation from the equilibrium pressure) is usually averaged over time and/or space, and a square root of this average provides a root mean square (RMS) value. For example, 1 Pa RMS sound pressure (94 dBSPL) in atmospheric air implies that the actual pressure in the sound wave oscillates between (1 atm

Pa) and (1 atm

Pa) and (1 atm

Pa), that is between 101323.6 and 101326.4 Pa. As the human ear can detect sounds with a wide range of amplitudes, sound pressure is often measured as a level on a logarithmic decibel scale. The sound pressure level (SPL) or Lp is defined as

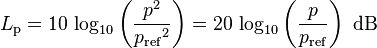

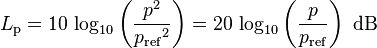

Pa), that is between 101323.6 and 101326.4 Pa. As the human ear can detect sounds with a wide range of amplitudes, sound pressure is often measured as a level on a logarithmic decibel scale. The sound pressure level (SPL) or Lp is defined as

where p is the root-mean-square sound pressure and

is a reference sound pressure. Commonly used reference sound pressures, defined in the standard ANSI S1.1-1994, are 20 µPa in air and 1 µPa in water. Without a specified reference sound pressure, a value expressed in decibels cannot represent a sound pressure level.

is a reference sound pressure. Commonly used reference sound pressures, defined in the standard ANSI S1.1-1994, are 20 µPa in air and 1 µPa in water. Without a specified reference sound pressure, a value expressed in decibels cannot represent a sound pressure level.

Since the human ear does not have a flat spectral response, sound pressures are often frequency weighted so that the measured level matches perceived levels more closely. The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) has defined several weighting schemes. A-weighting attempts to match the response of the human ear to noise and A-weighted sound pressure levels are labeled dBA. C-weighting is used to measure peak levels.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sound

Sound - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

We know that Sound waves take approximately 5 seconds to travel 1 mile. Using this information, it is possible to measure one's distance from a lightning bolt.

Physics of sound

Sound can propagate through compressible media such as air, water and solids as longitudinal waves and also as a transverse waves in solids (see Longitudinal and transverse waves, below). The sound waves are generated by a sound source, such as the vibrating diaphragm of a stereo speaker. The sound source creates vibrations in the surrounding medium. As the source continues to vibrate the medium, the vibrations propagate away from the source at the speed of sound, thus forming the sound wave. At a fixed distance from the source, the pressure, velocity, and displacement of the medium vary in time. At an instant in time, the pressure, velocity, and displacement vary in space. Note that the particles of the medium do not travel with the sound wave. This is intuitively obvious for a solid, and the same is true for liquids and gases (that is, the vibrations of particles in the gas or liquid transport the vibrations, while the average position of the particles over time does not change). During propagation, waves can be reflected, refracted, or attenuated by the medium.[4]

The behavior of sound propagation is generally affected by three things:

- A relationship between density and pressure. This relationship, affected by temperature, determines the speed of sound within the medium.

- The propagation is also affected by the motion of the medium itself. For example, sound moving through wind. Independent of the motion of sound through the medium, if the medium is moving, the sound is further transported.

- The viscosity of the medium also affects the motion of sound waves. It determines the rate at which sound is attenuated. For many media, such as air or water, attenuation due to viscosity is negligible.

When sound is moving through a medium that does not have constant physical properties, it may be refracted (either dispersed or focused).

Spherical compression (longitudinal) waves

The mechanical vibrations that can be interpreted as sound are able to travel through all forms of matter: gases, liquids, solids, and plasmas. The matter that supports the sound is called the medium. Sound cannot travel through a vacuum.

Longitudinal and transverse waves

Sound is transmitted through gases, plasma, and liquids as longitudinal waves, also called compression waves. Through solids, however, it can be transmitted as both longitudinal waves and transverse waves. Longitudinal sound waves are waves of alternating pressure deviations from the equilibrium pressure, causing local regions of compression and rarefaction, while transverse waves (in solids) are waves of alternating shear stress at right angle to the direction of propagation. Additionally, sound waves may be viewed simply by parabolic mirrors and objects that produce sound. [5]

The energy carried by an oscillating sound wave converts back and forth between the potential energy of the extra compression (in case of longitudinal waves) or lateral displacement strain (in case of transverse waves) of the matter, and the kinetic energy of the displacement velocity of particles of the medium.

Sound wave properties and characteristics

Sinusoidal waves of various frequencies; the bottom waves have higher frequencies than those above. The horizontal axis represents time.

Sound waves are often simplified to a description in terms of sinusoidal plane waves, which are characterized by these generic properties:

- Frequency, or its inverse, the period

Sound that is perceptible by humans has frequencies from about 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz. In air at standard temperature and pressure, the corresponding wavelengths of sound waves range from 17 m to 17 mm. Sometimes speed and direction are combined as a velocity vector; wave number and direction are combined as a wave vector.

Transverse waves, also known as shear waves, have the additional property, polarization, and are not a characteristic of sound waves.

Speed of sound

U.S. Navy F/A-18 approaching the sound barrier. The white halo is formed by condensed water droplets thought to result from a drop in air pressure around the aircraft (see Prandtl-Glauert Singularity).

The speed of sound depends on the medium that the waves pass through, and is a fundamental property of the material. The first significant effort towards the measure of the speed of sound was made by Newton. He believed that the speed of sound in a particular substance was equal to the square root of the pressure acting on it (STP) divided by its density.

This was later proven wrong when found to incorrectly derive the speed. French mathematician Laplace corrected the formula by deducing that the phenomenon of sound traveling is not isothermal, as believed by Newton, but adiabatic. elastic modulus, c = velocity of sound, and

Those physical properties and the speed of sound change with ambient conditions. For example, the speed of sound in gases depends on temperature. In 20 °C (68 °F) air at sea level, the speed of sound is approximately 343 m/s (1,230 km/h; 767 mph) using the formula "v = (331 + 0.6 T) m/s". In fresh water, also at 20 °C, the speed of sound is approximately 1,482 m/s (5,335 km/h; 3,315 mph). In steel, the speed of sound is about 5,960 m/s (21,460 km/h; 13,330 mph). The speed of sound is also slightly sensitive (a second-order anharmonic effect) to the sound amplitude, which means that there are nonlinear propagation effects, such as the production of harmonics and mixed tones not present in the original sound (see parametric array).

Perception of sound

Human ear

A distinct use of the term sound from its use in physics is that in physiology and psychology, where the term refers to the subject of perception by the brain. The field of psychoacoustics is dedicated to such studies.

The physical reception of sound in any hearing organism is limited to a range of frequencies. Humans normally hear sound frequencies between approximately 20 Hz and 20,000 Hz (20 kHz),[9] Both limits, especially the upper limit, decrease with age.

Other species have a different range of hearing. For example, dogs can perceive vibrations higher than 20 kHz, but are deaf below 40 Hz. As a signal perceived by one of the major senses, sound is used by many species for detecting danger, navigation, predation, and communication. Earth's atmosphere, water, and virtually any physical phenomenon, such as fire, rain, wind, surf, or earthquake, produces (and is characterized by) its unique sounds.

Sound pressure is the difference, in a given medium, between average local pressure and the pressure in the sound wave. A square of this difference (i.e., a square of the deviation from the equilibrium pressure) is usually averaged over time and/or space, and a square root of this average provides a root mean square (RMS) value. For example, 1 Pa RMS sound pressure (94 dBSPL) in atmospheric air implies that the actual pressure in the sound wave oscillates between (1 atm

where p is the root-mean-square sound pressure and

Since the human ear does not have a flat spectral response, sound pressures are often frequency weighted so that the measured level matches perceived levels more closely. The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) has defined several weighting schemes. A-weighting attempts to match the response of the human ear to noise and A-weighted sound pressure levels are labeled dBA. C-weighting is used to measure peak levels.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sound

Sound - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Last edited: