Thousands of Chinese migrants each year are trekking across Latin America to reach the United States border

www.economist.com

Thousands of Chinese migrants each year are trekking across Latin America to reach the United States border

The walls of the hotel lobby in downtown Quito, the capital of Ecuador, were plastered with notices in Mandarin. “Leaving for Colombia tomorrow and looking for buddies, WeChat id below”, read one handwritten flyer. A poster advertised an “all-inclusive package for crossing the jungle in Panama, 1,700USD”. Dozens of Chinese people were milling around: young people, old people, families with small children. Some were wearing large backpacks or dragging suitcases. All were on their way to a new life in America.

Xing Weisen, a 35-year-old man with a full beard, was chattier than the other Chinese guests at the hotel that I visited in May. It had taken him almost a week to reach Quito from his home in Xining, a city in western China. He’d gone to Ecuador because it was the nearest country to the border with North America that admitted Chinese people without a visa. As he told me his story, Xing smoked his way through the last packet of cigarettes that he had brought with him from home.

Xing had been desperate to leave China. In 2020 both his parents died: his mother from cancer, his father from heart disease.

Xing had sold nearly all his possessions to pay for their medical treatment. “There is no social safety net in China, and I learned that the hard way,” he said. He borrowed money from friends to start an online business selling sports merchandise, but struggled during the pandemic, he said, because of

China’s stringent “zero-covid” policy. During prolonged lockdowns, factories closed and demand dwindled.

There has been a big rise in Chinese people making the dangerous trek from South to North America, a well-trodden route for

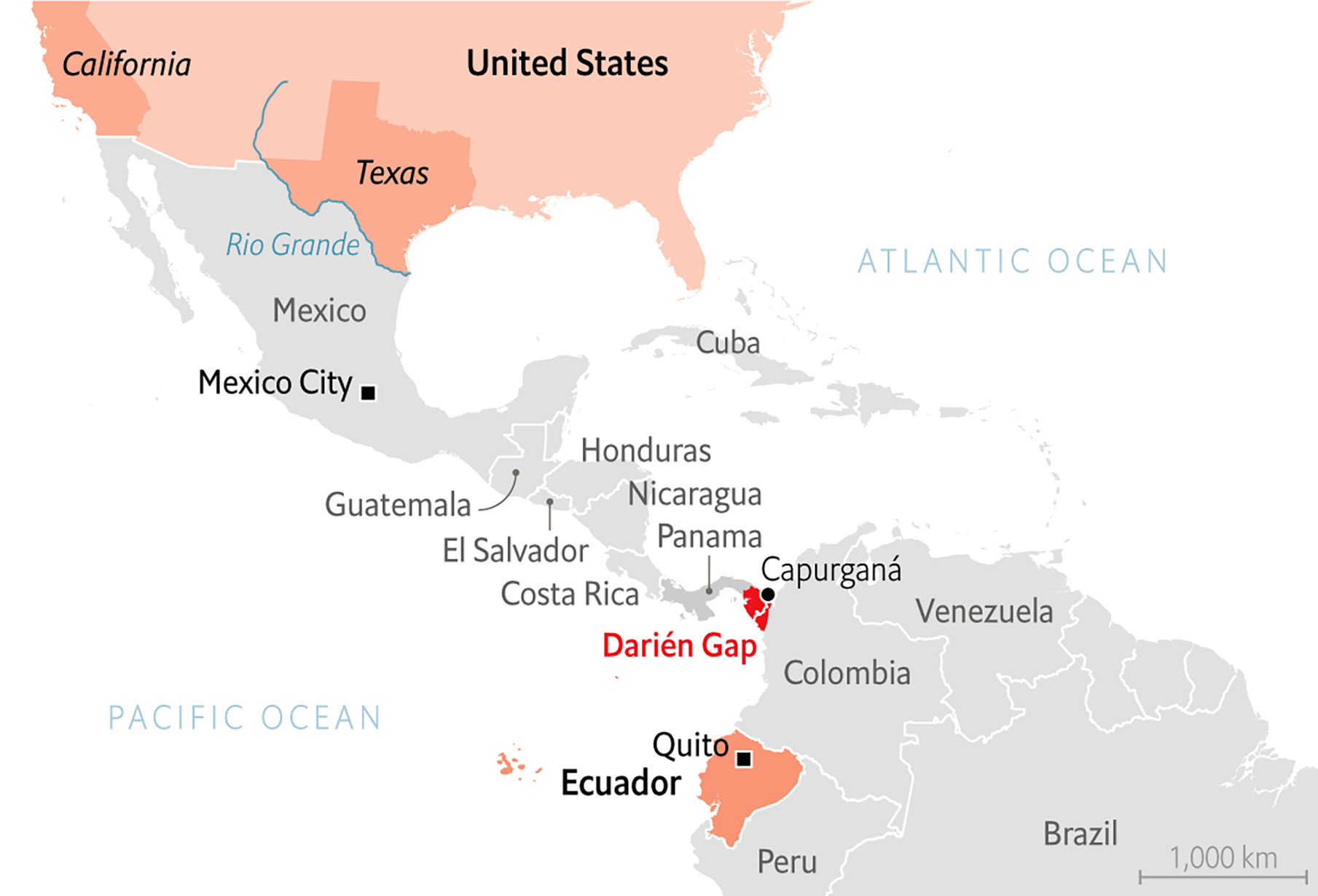

Latin American migrants. In 2021 the authorities in Panama counted 200 Chinese migrants crossing the Darién Gap, a treacherous stretch of rainforest between South and Central America; last year it was ten times that number. In the first half of this year alone, almost 9,000 Chinese people crossed the Darién Gap.

In 2021 the authorities in Panama counted 200 Chinese migrants crossing the Darién Gap; last year it was ten times that number

I spoke to more than 50 Chinese people on the migrant trail in Latin America. Their reasons for leaving China were diverse: some feared imprisonment over things they had written on social media; some mentioned the social unacceptability of being gay; many, like Xing, were finding it hard to make a living. Although the government ended its zero-covid policy at the start of the year,

the economy remains sluggish. Consumer spending has slowed and in cities more than one in five young people are unemployed.

Broke and hopeless, Xing decided he needed a fresh start. “That country is not a place for anyone who wants to live life with dignity,” he said. America was the “obvious choice” for him and other migrants, said Xing. He was a child of the 1990s, when relations between the two countries were more amicable. Unlike their parents, millennials were exposed to American culture growing up.

Xing first tried to emigrate to America last year but said his visa application had been rejected without a reason being given. He had applied for a tourist visa, which he was planning to outstay – all the Chinese migrants I met had intended to go down this route. Last year America rejected almost one in three Chinese applications for tourist visas; in 2019 it rejected fewer than one in five. Xing reckons American immigration officials viewed his application with suspicion because he didn’t have a stable job.

This time he didn’t bother applying for a tourist visa. He joined groups on the messaging apps WeChat and Telegram, where people shared information about the journey from China to America. The groups had tens of thousands of members. “There are so many Chinese trying to leave, you have no idea,” he told me. (It is impossible to say how many people are emigrating from China: emigrants have no reason to tell their own government where they are going and often have good reason to hide their intentions from the government of the place they are moving to.)

Xing avoided booking a plane ticket out of mainland China, having read too many stories about migrants being turned away as they tried to board planes. In 2020 the Chinese government banned people from leaving or entering the country unless their trip was “necessary or urgent”, citing the need to limit the spread of covid-19. Despite the end of zero-covid, Xing was worried that immigration officials would find a reason to stop him from flying to South America: “How do you know a government like China’s would not just make a 180-degree turn?...I didn’t want to risk anything.”

Instead Xing would get a train to Hong Kong (where, he said, the authorities didn’t care about the onward journeys of Chinese nationals), then a plane to Thailand, another to Istanbul, before finally flying to Ecuador. He didn’t tell anyone about his plan. The night before he left, he met his best friend Quan for drinks. As they said their goodbyes Xing embraced his friend tightly, surprising Quan – in China, friends aren’t usually tactile with one another. “I had to do it because it might be the last time I would see him,” said Xing.

He invited me to join him on his journey to America. In two days he would get a bus to Tulcán, an Ecuadorian town on the border with Colombia. But first he had some errands to run in Quito. Xing went to a health clinic to get vaccinated for yellow fever, a mosquito-borne disease which is prevalent in the rainforest. Then he went to a convenience store to stock up on condoms.

“I am never going back to China. Even if that means I have to crawl to America or die on my way there”

That evening in his hotel room I watched Xing lay out $2,500 in banknotes on the bed, then form them into neat stacks. He tore open the condom wrappers, before carefully sliding each condom over a wad of cash. He tied a knot in the condoms, opened a shampoo bottle and slid the cash-filled condoms inside. “This is how you make sure corrupt cops don’t find the money and confiscate it!” He was determined not to fall foul of the Colombian police. “I am never going back to China,” Xing told me. “Even if that means I have to crawl to America or die on my way there.”

The hotel was run by a Chinese woman in her 50s – she asked me to call her Ana – who moved from Beijing nearly 20 years ago. Her accent was still strong and her speech was peppered with Beijing dialect, giving her the air of nonchalance that people from the city are known for. Originally, said Ana, the business was aimed at Western tourists, but early in 2022 she noticed she was taking bookings from growing numbers of Chinese. She would overhear them in the lobby discussing plans to smuggle themselves into America. Before she knew it, Chinese migrants became virtually the only guests at the hotel.

“I never wanted this place to be a migrant hub, but what can you do?” she told me as we sat in her small office. “We are all Chinese. Do I just turn them away or see them go on this dangerous journey without helping them?” She dispenses travel advice to the migrants and helps them book bus tickets. Ana showed me a storeroom filled with suitcases and abandoned clothes, left by migrants in the past month. “They could not carry them on the road,” she said. By 11am that morning, she had already waved goodbye to 14 migrants, wishing them luck on their travels.

Xing left his suitcase in Ana’s storeroom early one morning before heading to a bus terminal, where competing tour operators jostled for business. “China! China!” they shouted, as they banged on the windows of the ticket offices. “Tu-er-can?” said one Ecuadorian man affecting the pronunciation of the border town’s name in a Mandarin accent. But Xing didn’t need any help – he had already contacted a snakehead, a people smuggler who caters to a Chinese clientele.

There are snakeheads in every country on the migrant trail, and on his journey Xing would deal with several of them. Most are based in Necocli, not far from the Darién Gap, and act like illegal tour operators, employing local guides to help migrants make the crossing, where hazards include uneven terrain, flash floods, landslides and armed bandits. Li Bai, the most famous of them, is said to have hundreds if not thousands of Chinese customers.

No one knows much about Li Bai, whose pseudonym is borrowed from a Tang Dynasty poet. According to Xing, he is “probably Colombian…Most Chinese deal with his minions, who are actually Chinese.” Li Bai’s most expensive package costs $1,150 and includes transport on horseback through the Darién Gap, shortening a journey that might be five days on foot to just 36 hours. One of Li Bai’s assistants told me that the service had been designed with Chinese migrants in mind: “they are usually the ones with the thickest wallets and would pay up to minimise the dangers in the jungle.”

Li Bai was too expensive for Xing. He paid a few hundred dollars for his snakehead, who promised a safe passage through the Darién Gap within three days. Xing had carefully researched the different snakeheads before making his choice, talking to other migrants and obsessively reading messages on WeChat and Telegram. “I want to make sure the snakehead won’t abandon us in the middle of the jungle or demand more money halfway through,” he said.

It took three buses and a minibus ride to reach Necocli from Quito. Xing gazed at the scenery as we drove by: cattle grazing by lakes, snowy mountaintops, a sharp blue sky. “Maybe one day in the future, I can just live in the Andes as a cowherd and have a tranquil life,” he said. Drifting in and out of sleep, we both overheard conversations that would be risky in China. “[President] Xi Jinping is essentially an emperor now,” said one migrant. Other migrants piped up, talking about the pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong in 2019 and the demonstrations against zero-covid in Shanghai last year. Xing turned to me and said, “This is why I left China – to places where people can talk freely.”

One of the buses was stopped and searched by police three times. “****, I hope they don’t look inside my shampoo bottle,” said Xing when he saw the cops examining the shoulder straps of someone’s backpack for any unusual lumps. To Xing’s relief, the police ignored his toiletries, confiscating only the $20 bill he had hidden in a cigarette box. “All hail the condoms,” said Xing.

At Necocli, Xing took a ferry to Capurganá, a seaside village in northern Colombia, where the Darién Gap begins. After they disembarked, the migrants were each handed a wristband, its colour corresponding to which snakehead they were using. Li Bai’s clients wore blue. Tuk-tuk drivers collected the migrants and took them a short distance to an open field, passing a few checkpoints erected by traffickers. In the field, armed men scrutinised the migrants’ faces and names on their documentation, comparing them to the photos on their phones.

This was the last I saw of Xing before he began his trek – I had to leave Capurganá in something of a hurry. Li Bai’s assistant had texted me to say that some snakeheads were “taking notice” of an Asian man without any wristband. ”This is a matter of life or death so leave now,” wrote the assistant snakehead. I hunkered down overnight in a hotel in the busiest part of Capurganá, before getting the boat back to Necocli without any incident. It felt strange leaving Xing just before he embarked on the most perilous part of his journey. A fortnight later he sent me a brief message telling me he had safely made it to Mexico.

I rushed to meet him in Mexico City, more than 2,000 miles from where we had parted ways. Xing had only a few hours in the city, so he suggested we meet at a bus terminal. His beard had grown more unruly and skin tone darker. Yet despite bruises on his leg, a lost tooth, and a lingering fever, he seemed more relaxed than he had been in Colombia. Seated next to him was Luis, a Venezuelan man in his early 30s, who had come to Xing’s aid when he had slipped on a muddy hill – the cause of the lost tooth, as well as a sprained ankle. (The only Spanish word that Xing knew was

amigo but the two men managed to communicate through translation apps and gestures.)

Eventually they limped out of the jungle, and the snakehead shunted them towards the next stage of their journey. They crossed four more countries on trucks, tuk-tuks, taxis, motorbikes, speedboats and trains. “The biggest danger after the Darién Gap is reckless driving,” Xing said. “Snakeheads try to make as much money as possible, so they’d stuff 14 people in a car with a capacity of seven.”

En route, Xing texted his friend, Quan, in China. It had been nearly three weeks since he left China, and that was the first time Xing had admitted to him where he’d gone. “You know how I told you I was going travelling for a few weeks?” he said. “I’m now in Central America, and maybe I’ll die on the road, I don’t know, but I’m going to the us.” It was about 5am in China when Quan got Xing’s message. He sent his friend a voice note: “Are you fucking crazy?”

Watching him sit on the floor of the bus terminal in Mexico City, I wondered if he’d ever asked himself the same question. “Yes, I am crazy,” he said. “But what’s crazier is that the only way to a life with dignity is a journey without dignity.”

“The biggest danger after the Darién Gap is reckless driving. Snakeheads try to make as much money as possible, so they’d stuff 14 people in a car with a capacity of seven”

Xing was weighing up his options for the last leg of his journey. He could pay another snakehead to take him across the Rio Grande into Texas, though he did not have enough money to pay for a boat and couldn’t swim. Or he could cling to the “Beast”, a Mexican freight train that has become a dangerous last resort for migrants crossing the border.

As he prepared to leave Mexico City, Xing quit the Telegram and WeChat groups that he had so relied on to plan his trip. “It wouldn’t look good if the us immigration officer saw you were in many chat groups,” Xing told me. He stumbled upon a chilling photo of a Chinese woman covered in blood. “Anyone know this woman’s family?” read the message. “She just died on the sea off the coast of Capurganá, somebody please inform her family.”

Afortnight passed before I heard from Xing again. “I made it to California!” he texted me on WhatsApp. We jumped on a video call. Sitting in a Chinese restaurant in Monterey Park, Xing had just finished a bowl of Lanzhou noodles – a food he had grown up eating. He had shaved his beard and had a haircut. “Man, I paid $15 for this bowl of noodles, but it would’ve been at most $3 in China,” he said, laughing, before sinking a large glass of iced Coke.

After letting out a loud burp, Xing told me the story of the last stretch of the journey. Quan had sent him $2,000 so he could catch the boat. “If he didn’t wire me money, I would probably be dying on the train now,” Xing said. When Xing and Luis, along with other Chinese migrants, arrived at the banks of the Rio Grande, they found the snakehead snorting cocaine as he gave them their instructions. “Don’t take any photos or talk too loud – you are almost there.”

Xing gave the snakehead his phone, and then the man dropped a pin on Google Maps. “Go to this place if you want to and there will be immigration officers,” he said. Although his visa application had been rejected and he had entered America illegally, Xing was hopeful that the immigration authorities would look kindly on his claim for asylum. Living in the country legally was “the only way”, he said. “I wouldn’t want to be deported back to China for not having documents.”

As the boat approached the shore, Xing’s excitement exceeded his anxiety. “The us is just a few metres away now,” he remembered thinking. Less than ten minutes later, without any ceremony, Xing and Luis stepped onto American soil. The group were elated on the two-mile walk to immigration control. “Look, how clean this place looks!” one Chinese man said, pointing at a house with an American flag on top and a neatly mowed lawn in front. A truck driver honked his horn, then rolled down his window and flipped a finger at the migrants. “I couldn’t understand what he was saying but I heard ‘China’ and he was angry, so maybe he didn’t want us Chinese there,” said Xing.

On the chat groups someone posted a photo of a Chinese woman covered in blood. “Anyone know her family?” read the message. “She just died on the sea off the coast of Capurganá”

As they arrived at immigration control, Xing started to feel nervous. The migrants were instructed to toss all of their belongings into big plastic bags, then were patted down. “It was a bit chaotic, but the officers were unexpectedly very nice to us,” Xing said. They gave them food, then a truck came to take them to a processing centre.

Having done his research, Xing knew where they were going – a detention centre that Chinese migrants called “tin-foil house”, after the aluminium blankets they were given to keep warm. It was early June in southern Texas and the days were hot, but the nights could be freezing. Migrants might be held here for days, weeks or even months before being set free or deported.

Xing and Luis were separated. It was the last time they saw each other (later, Xing learned Luis had been deported to Mexico). Xing was put in a room with about 30 migrants, including five other Chinese people. With fluorescent lights and bare walls, it felt like a prison. The migrants huddled together on the floor: there were no mattresses and the foil blankets were useless against the cold. Xing saw people banging their heads against the wall. “Some of them were going crazy because of how long they had stayed in that room,” he said. He was scared he could be stuck there for months. But within two days, Xing was summoned by an immigration officer.

“Yes, I am crazy,” said Xing. “But what’s crazier is that the only way to a life with dignity is a journey without dignity”

The official handed Xing a stack of papers, explaining that he needed to sign them in order to be released. Xing, who couldn’t read English, had no idea what the papers said and was too scared to ask the officer. (Afterwards he scanned the text with Google Translate and found out his asylum claim would be heard by a judge later in the year.) The officer handed Xing a mobile phone. On the screen were instructions, in badly translated Mandarin, to check in using the phone each Tuesday at 3pm, and to stay within a 75-mile radius of his primary residence. Volunteers helped Xing buy a bus ticket to Houston, Texas, and a plane ticket from there to Los Angeles, where he planned to stay with some other Chinese migrants he’d met along the way.

As the sun set in California, Xing stepped out of the restaurant. He was eager to show me his surroundings on our video call. There was a big car park circled by an array of Chinese businesses: restaurants, car-rental agencies, translation services. As I accompanied him, virtually, down a quiet residential street, Xing giggled, covering his mouth because of his lost tooth. “I told you I would make it to America. Next step: make it

in America.”■

Some names have been changed in this article

Shawn Yuan