ghazi52

PDF THINK TANK: ANALYST

- Joined

- Mar 21, 2007

- Messages

- 104,413

- Reaction score

- 106

- Country

- Location

Clay Pot Irrigation System

The Potter’s Method

You can make your own ollas by hand with wet clay using several methods. However, no matter which one you use, the pots will need to be fired in a kiln, which can usually be found at a clay store, pottery studio, and at a college or university. The pots are made from a mixture of clay and sand at a ratio of 4:1, which will give it an effective porosity ranging from 10-15%. Depending on the clay, you can add, rice hulls, or sawdust at a ratio of up to 1:4 to increase the porosity of the pots. You could also simply add more sand, although using a more crude, impure clay

(which has a varied mix of particulate sizes) will result in larger pores during the firing process. Or, you can mix 20% sand with 20% quality clays, or the same percent of sifted rice hulls or sawdust. After mixing the clay, use a potter’s wheel to mold it into different shapes, typically with a spherical or round body and a flat bottom. The pots are then tempered by baking them at high temperatures.

Firing the ollas makes the clay hard and strong, while still allowing water to pass through. The temperatures required can vary, depending on the quality and mixtures of your clay, the type of oven used when baking, and your desired porosity, and could range anywhere from 200° to over 1,000° C. Small-scale, earthen-ware manufacturers generally temper their ceramic pots at 1200° C. A course, red clay with sand impurities and a mixture with 20% or less of straw should be fired at around 800° F, or around 430° C. Closed-oven firing at temperatures exceeding 450° C are ideal.

Generally, the pots should not be fired much above 1,000° C, or their porosity will be limited. Adding more grog (ground old ceramic) will increase porosity by burning out the filler, leaving uniform pores and a high-quality pot. It is important to find the optimum temperature for your pots. If you make it too hot, the clay will become water-tight, making the ollas useless for our purposes. However, if the pots are not heated enough, then they may breakdown in the soil, causing leakages.

The Coil-Method

This method builds the pot piece-by-piece, in layers from the bottom up, by laying long, rolled coils on top of each other around the sides of a bowl or plate to build the pot. Begin by pinching a ball of wet clay to create a bowl-shape. Use this as the base of your olla, and build up around it from there. Or, you can take the bottom of an old, terra-cotta plate (puki), and lay down a tortilla-shaped piece of clay on top of it.

Then, roll a lump of clay between your palms, creating a long clay rope of uniform thickness, and form the base of the olla by pinching and pressing this coil onto the sides of the clay tortilla with one hand, while turning the bowl or puki with your other hand. Add successive layers of coils until the vessel is completed.

The Casting Method

You can also make the jars out of a mold-casting. This is an excellent way to mass-produce ollas if you can successfully cast them. To make the urns, create plaster of Paris molds from pumpkins, squash, or gourds of various sizes. Then pour liquid clay into the molds to shape the urns, and fire them in the kiln to solidify the clay.

Using Milk Jugs as Ollas

You can also repurpose some used 1-gallon milk jugs to turn them into artificial ollas. Take your empty milk jugs, fill them with water, and freeze them overnight. Poke multiple small holes into the sides of the jug with a nail or ice pick and hammer. When planting near a wall or walkway, you may want to poke holes on only two sides of the jug, so that the water flows to your plants and not on your pathway. Bury the milk jugs, plant, and water in the same manner as the ollas.

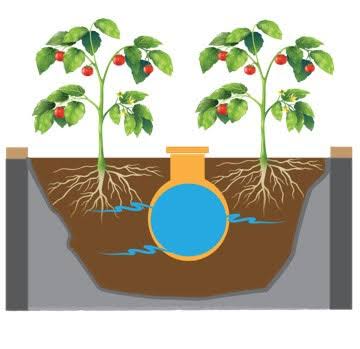

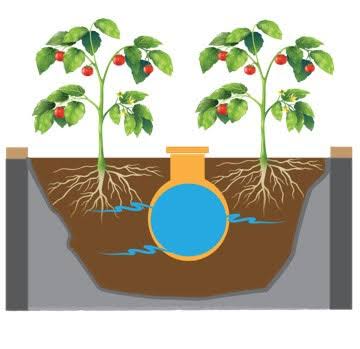

Burying and Watering The Ollas

Start by digging a planting hole about three times as wide and twice as deep as the clay pot. If you encounter clay in your topsoil, discard and replace it with finer, higher-quality soils, as it makes it hard for the water to penetrate. In very heavy soil, you may wish to add sand or gypsum to improve its characteristics. In either case, you will want to fertilize the soil to add more nutrients for the plants. Simply take half of the soil you just removed, break it up using a spade or fork, and add it back into the bottom of the pit. Take the other half of the soil and mix in 1/3 of compost, aged manure, fertilizer, or potting mix with dolomite.

Before burying the ollas completely, it’s best to first fill them and check for leaks. Once that’s done, place the pot in the pit on top of the loose soil, and fill the pit around it with the fertilizer-soil mix. Then bury it up to its neck so that the top is about 2 cm above the surface of the surrounding soil. The top of the clay pot should remain exposed above ground so it can be refilled. To make the top of the pots easier to see, and to reduce evaporation, paint the top rims with white paint. The upper body of the buried clay pot can also be partially painted to reduce water use, but be sure your paints do not include any harmful materials, such as lead or cadmium.

When finished burying the pots, put mulch around the exposed neck at the surface to reduce water evaporation. Then, fill them with water and put a cover over the opening. Keeping the mouth of the jar fully covered prevents insects, animals, and debris from getting inside, in addition to reducing water loss through evaporation. If there are no fitted lids for the jars, you can use corks, plastic lids, cups, metal dishes, flat rocks, clay plates, shells, ceramic tiles, or even pot holders, depending on the size of the hole.

Water takes between 24 and 72 hours to flow through an olla. Depending on factors such as the plant’s water needs, pot size, soil type, time of year, and environment, the ollas may need re-filling every 2 to 3 days for small pots, or once or twice per week for larger ones. To keep the system working optimally, add more water to the pots as needed, and avoid letting them get completely dry. In order to avoid build up of salt residues along the inside surface of the olla that may prevent desired seepage, add water whenever the water level in the olla falls below 50%.

Domestic water effluent, or greywater from kitchens, can be used to refill the pots. Although, it should be filtered first, or otherwise it will clog the pours. You may also supply the olla with water mixed with liquid fertilizer. Simply mix the fertilizer or compost seed in the water, and use it as normal. The liquid fertilizer is more expensive than the granular kind, although, with the liquid variety, you’ll only need about 1/4 to 1/2 of the amount (per unit area of land) compared to granular fertilizers. This is due to the tremendous efficiency of the delivery of nutrients directly to the plant’s roots. Do not add this too often, however, as particles could build up and clog the pours in the clay.

Planting With Ollas

The system is useful for annual and perennial plants, woodlots, and horticultural, orchard or plantation crops. Tests and research conducted around the world — including China, Pakistan, India, Mexico, Brazil, Iran, California, Arizona, and New Mexico – have found that the following plants are suitable to use with clay pot irrigation:

You can plant from cuttings or transplants, or you can raise seedlings in situ instead of transporting them from nurseries. However, ollas are not very good for seed germination, as there won’t be enough surface moisture to water them. A small amount of water should be added to the seed spot or transplant to help wet the soil and establish capillary action from the buried clay pot. If starting with plants that already have roots, water the surface until their roots grow low enough to establish themselves. If planting with cuttings, try setting up a double clay pot to propagate them. Take a sealed pot and set it inside a larger one with an open drain. Fill the space between them with sandy potting mix, and put the cuttings in there. This way, they will be kept moist but still get oxygen.

It has been noted that plants with thick roots, and those with woody perennial plant root growth, will likely grow right through the pots and break them. This makes the pots less useful for long-term tree irrigation, but they can still be used for system establishment. Trials in Pakistan using 8-inch clay pots, refilled every two to four weeks, showed that tree seedlings irrigated with buried clay pots had a survival-rate of 96.5%, compared to 62% for hand watering.

The seedlings grown with buried clay pots were also 20% taller. After eight months, all tree seedlings grown around the pots were alive and well, while all of the trees irrigated with the same amount of water using basin irrigation had died. Examination of the root distributions showed that several roots had wrapped themselves around the pot, while two dominant tap roots went straight down to considerable depth. This shows that buried clay pot irrigation can help develop a sufficient root system for long term survival and permanent installation of fruit, nut, and desert trees like pistachio, mesquite, acacia, or eucalyptus. The pot only needs to be filled regularly during the first year and can then be removed.

Be careful when producing fast-growing and spreading plants, like squash and melon vines with big leaves, as they may not be able to get enough water in some situations. Some sensitive species of plants could also be prone to pest or disease because of the constant levels of moisture in the soil. Heavy rains could exacerbate these problems when too much extra moisture is added to the garden. Beware of plants with invasive root systems, as they can grow out horizontally to steal water from the ollas.

When planting with ollas, there is the potential for breakage if left in the ground in areas with a winter freeze. In temperate climates, dig the pots up at the end of the growing season to prevent breakage. Burying the pot further underground, about 4-inches or so under the surface, may help protect it from freezing. The longevity of most ollas (without frost) is unknown, but estimated to be 2- to 5-years, depending on the quality of the clay, the mineral content in the water, and soil temperature swings. Prolonged use is likely to decrease porosity and clog up the pots over time. If this happens, soak the pots in water and scrub them clean, or re-fire to clear out the pores.

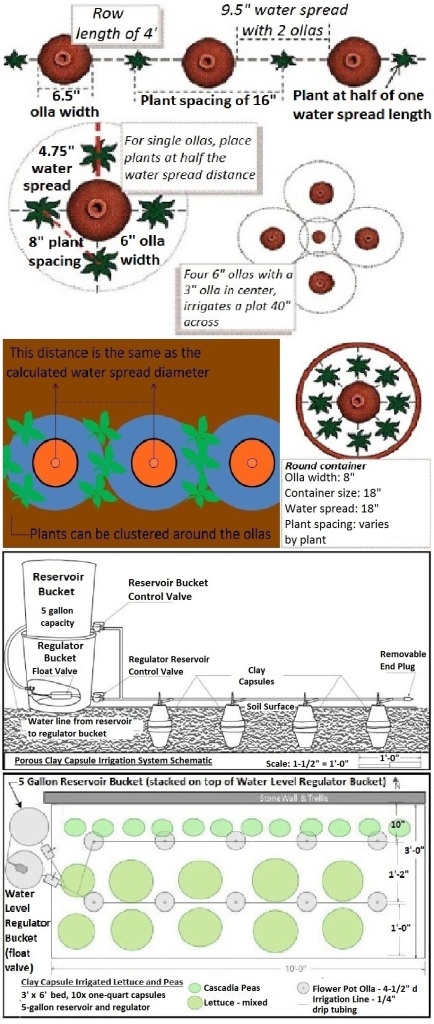

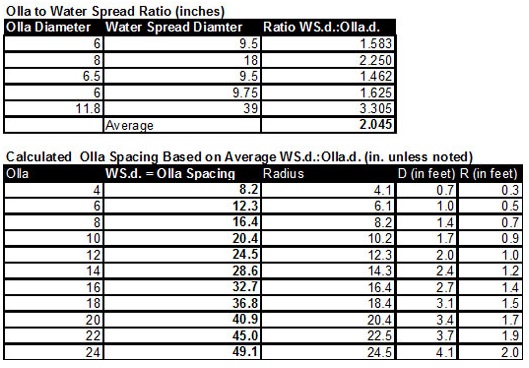

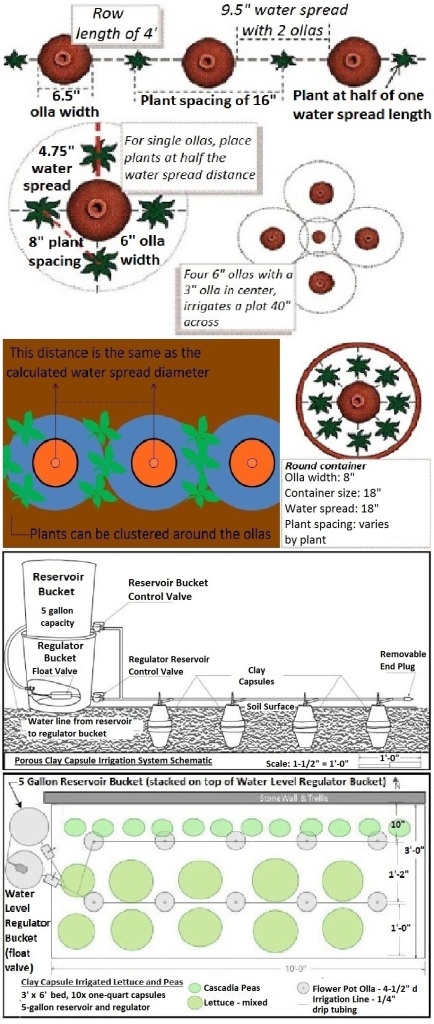

Spacing

The correct spacing of your plants will depend on the shape and size of the ollas, and of the crops you’re growing. Not much research is available as to the optimal spacing of plants around the ollas, but some women in the developing world used clay pots with a capacity of 5-liters each, and buried them at 0.5 m intervals in prepared seed beds. Ancient practices buried many pots on large swaths of land, using 530 pits per hectare (210 pits per acre), with each pit being 70 cm (24-inches) across and 12 cm (5-inches) deep. To each pit was added 18 kilograms (38 lbs.) of manure, and mixed well with an equal amount of dirt. An earthen jar of 6-liters (1.5-gallons) was buried in the center of the pit and filled with water to the brink.

Pots of about 1.5-gallons will seep water out to about 18-inches. The general rule of thumb is that each olla will water outwards at a distance about the same length as its radius. For optimal water utilization, arrange the pots in clusters, separated from each other at a distance equal to the width of their diameter or more, and plant in circles around them within about 18-inches around the base of the pot.

In general, place your pots about 3 m (9-feet) apart for vine crops, and 1-1.5 m (3- to 5-feet) apart for corn and other tall-growing plants. The seeds or plants should be placed no less than about 1/2 of the radius away from the edge of the pot, and no more than the length equal to the diameter away from the edge, to maximize water absorption. It is helpful to leave a space between plants on one side of the pot to make it easier to lift the lid and refill it as the plants grow larger. You can also use pots in raised beds and containers. Simply use the 1-radius rule to find out how large your containers and beds need to be.

The Potter’s Method

You can make your own ollas by hand with wet clay using several methods. However, no matter which one you use, the pots will need to be fired in a kiln, which can usually be found at a clay store, pottery studio, and at a college or university. The pots are made from a mixture of clay and sand at a ratio of 4:1, which will give it an effective porosity ranging from 10-15%. Depending on the clay, you can add, rice hulls, or sawdust at a ratio of up to 1:4 to increase the porosity of the pots. You could also simply add more sand, although using a more crude, impure clay

(which has a varied mix of particulate sizes) will result in larger pores during the firing process. Or, you can mix 20% sand with 20% quality clays, or the same percent of sifted rice hulls or sawdust. After mixing the clay, use a potter’s wheel to mold it into different shapes, typically with a spherical or round body and a flat bottom. The pots are then tempered by baking them at high temperatures.

Firing the ollas makes the clay hard and strong, while still allowing water to pass through. The temperatures required can vary, depending on the quality and mixtures of your clay, the type of oven used when baking, and your desired porosity, and could range anywhere from 200° to over 1,000° C. Small-scale, earthen-ware manufacturers generally temper their ceramic pots at 1200° C. A course, red clay with sand impurities and a mixture with 20% or less of straw should be fired at around 800° F, or around 430° C. Closed-oven firing at temperatures exceeding 450° C are ideal.

Generally, the pots should not be fired much above 1,000° C, or their porosity will be limited. Adding more grog (ground old ceramic) will increase porosity by burning out the filler, leaving uniform pores and a high-quality pot. It is important to find the optimum temperature for your pots. If you make it too hot, the clay will become water-tight, making the ollas useless for our purposes. However, if the pots are not heated enough, then they may breakdown in the soil, causing leakages.

The Coil-Method

This method builds the pot piece-by-piece, in layers from the bottom up, by laying long, rolled coils on top of each other around the sides of a bowl or plate to build the pot. Begin by pinching a ball of wet clay to create a bowl-shape. Use this as the base of your olla, and build up around it from there. Or, you can take the bottom of an old, terra-cotta plate (puki), and lay down a tortilla-shaped piece of clay on top of it.

Then, roll a lump of clay between your palms, creating a long clay rope of uniform thickness, and form the base of the olla by pinching and pressing this coil onto the sides of the clay tortilla with one hand, while turning the bowl or puki with your other hand. Add successive layers of coils until the vessel is completed.

The Casting Method

You can also make the jars out of a mold-casting. This is an excellent way to mass-produce ollas if you can successfully cast them. To make the urns, create plaster of Paris molds from pumpkins, squash, or gourds of various sizes. Then pour liquid clay into the molds to shape the urns, and fire them in the kiln to solidify the clay.

Using Milk Jugs as Ollas

You can also repurpose some used 1-gallon milk jugs to turn them into artificial ollas. Take your empty milk jugs, fill them with water, and freeze them overnight. Poke multiple small holes into the sides of the jug with a nail or ice pick and hammer. When planting near a wall or walkway, you may want to poke holes on only two sides of the jug, so that the water flows to your plants and not on your pathway. Bury the milk jugs, plant, and water in the same manner as the ollas.

Burying and Watering The Ollas

Start by digging a planting hole about three times as wide and twice as deep as the clay pot. If you encounter clay in your topsoil, discard and replace it with finer, higher-quality soils, as it makes it hard for the water to penetrate. In very heavy soil, you may wish to add sand or gypsum to improve its characteristics. In either case, you will want to fertilize the soil to add more nutrients for the plants. Simply take half of the soil you just removed, break it up using a spade or fork, and add it back into the bottom of the pit. Take the other half of the soil and mix in 1/3 of compost, aged manure, fertilizer, or potting mix with dolomite.

Before burying the ollas completely, it’s best to first fill them and check for leaks. Once that’s done, place the pot in the pit on top of the loose soil, and fill the pit around it with the fertilizer-soil mix. Then bury it up to its neck so that the top is about 2 cm above the surface of the surrounding soil. The top of the clay pot should remain exposed above ground so it can be refilled. To make the top of the pots easier to see, and to reduce evaporation, paint the top rims with white paint. The upper body of the buried clay pot can also be partially painted to reduce water use, but be sure your paints do not include any harmful materials, such as lead or cadmium.

When finished burying the pots, put mulch around the exposed neck at the surface to reduce water evaporation. Then, fill them with water and put a cover over the opening. Keeping the mouth of the jar fully covered prevents insects, animals, and debris from getting inside, in addition to reducing water loss through evaporation. If there are no fitted lids for the jars, you can use corks, plastic lids, cups, metal dishes, flat rocks, clay plates, shells, ceramic tiles, or even pot holders, depending on the size of the hole.

Water takes between 24 and 72 hours to flow through an olla. Depending on factors such as the plant’s water needs, pot size, soil type, time of year, and environment, the ollas may need re-filling every 2 to 3 days for small pots, or once or twice per week for larger ones. To keep the system working optimally, add more water to the pots as needed, and avoid letting them get completely dry. In order to avoid build up of salt residues along the inside surface of the olla that may prevent desired seepage, add water whenever the water level in the olla falls below 50%.

Domestic water effluent, or greywater from kitchens, can be used to refill the pots. Although, it should be filtered first, or otherwise it will clog the pours. You may also supply the olla with water mixed with liquid fertilizer. Simply mix the fertilizer or compost seed in the water, and use it as normal. The liquid fertilizer is more expensive than the granular kind, although, with the liquid variety, you’ll only need about 1/4 to 1/2 of the amount (per unit area of land) compared to granular fertilizers. This is due to the tremendous efficiency of the delivery of nutrients directly to the plant’s roots. Do not add this too often, however, as particles could build up and clog the pours in the clay.

Planting With Ollas

The system is useful for annual and perennial plants, woodlots, and horticultural, orchard or plantation crops. Tests and research conducted around the world — including China, Pakistan, India, Mexico, Brazil, Iran, California, Arizona, and New Mexico – have found that the following plants are suitable to use with clay pot irrigation:

- Asparagus

- Basil

- Beans

- Bee Balm

- Broccoli

- Cabbage

- Celery

- Cilantro

- Collard Greens

- Corn

- Chiles

- Chiltepines

- Chives

- Cucumbers

- Eggplant

- Garlic

- Leeks

- Marigolds

- Melons

- Mints

- Onions

- Parsley

- Peppers

- Peas

- Poppies

- Potatoes

- Purslane

- Rosemary

- Rhubarb

- Scallions

- Shallots

- Strawberries

- Squash

- Sunflowers

- Tarragon

- Thyme

- Tomatoes

- Tomatillos

- Yarrow

You can plant from cuttings or transplants, or you can raise seedlings in situ instead of transporting them from nurseries. However, ollas are not very good for seed germination, as there won’t be enough surface moisture to water them. A small amount of water should be added to the seed spot or transplant to help wet the soil and establish capillary action from the buried clay pot. If starting with plants that already have roots, water the surface until their roots grow low enough to establish themselves. If planting with cuttings, try setting up a double clay pot to propagate them. Take a sealed pot and set it inside a larger one with an open drain. Fill the space between them with sandy potting mix, and put the cuttings in there. This way, they will be kept moist but still get oxygen.

It has been noted that plants with thick roots, and those with woody perennial plant root growth, will likely grow right through the pots and break them. This makes the pots less useful for long-term tree irrigation, but they can still be used for system establishment. Trials in Pakistan using 8-inch clay pots, refilled every two to four weeks, showed that tree seedlings irrigated with buried clay pots had a survival-rate of 96.5%, compared to 62% for hand watering.

The seedlings grown with buried clay pots were also 20% taller. After eight months, all tree seedlings grown around the pots were alive and well, while all of the trees irrigated with the same amount of water using basin irrigation had died. Examination of the root distributions showed that several roots had wrapped themselves around the pot, while two dominant tap roots went straight down to considerable depth. This shows that buried clay pot irrigation can help develop a sufficient root system for long term survival and permanent installation of fruit, nut, and desert trees like pistachio, mesquite, acacia, or eucalyptus. The pot only needs to be filled regularly during the first year and can then be removed.

Be careful when producing fast-growing and spreading plants, like squash and melon vines with big leaves, as they may not be able to get enough water in some situations. Some sensitive species of plants could also be prone to pest or disease because of the constant levels of moisture in the soil. Heavy rains could exacerbate these problems when too much extra moisture is added to the garden. Beware of plants with invasive root systems, as they can grow out horizontally to steal water from the ollas.

When planting with ollas, there is the potential for breakage if left in the ground in areas with a winter freeze. In temperate climates, dig the pots up at the end of the growing season to prevent breakage. Burying the pot further underground, about 4-inches or so under the surface, may help protect it from freezing. The longevity of most ollas (without frost) is unknown, but estimated to be 2- to 5-years, depending on the quality of the clay, the mineral content in the water, and soil temperature swings. Prolonged use is likely to decrease porosity and clog up the pots over time. If this happens, soak the pots in water and scrub them clean, or re-fire to clear out the pores.

Spacing

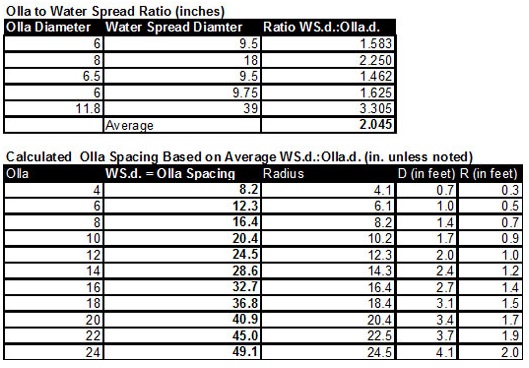

The correct spacing of your plants will depend on the shape and size of the ollas, and of the crops you’re growing. Not much research is available as to the optimal spacing of plants around the ollas, but some women in the developing world used clay pots with a capacity of 5-liters each, and buried them at 0.5 m intervals in prepared seed beds. Ancient practices buried many pots on large swaths of land, using 530 pits per hectare (210 pits per acre), with each pit being 70 cm (24-inches) across and 12 cm (5-inches) deep. To each pit was added 18 kilograms (38 lbs.) of manure, and mixed well with an equal amount of dirt. An earthen jar of 6-liters (1.5-gallons) was buried in the center of the pit and filled with water to the brink.

Pots of about 1.5-gallons will seep water out to about 18-inches. The general rule of thumb is that each olla will water outwards at a distance about the same length as its radius. For optimal water utilization, arrange the pots in clusters, separated from each other at a distance equal to the width of their diameter or more, and plant in circles around them within about 18-inches around the base of the pot.

In general, place your pots about 3 m (9-feet) apart for vine crops, and 1-1.5 m (3- to 5-feet) apart for corn and other tall-growing plants. The seeds or plants should be placed no less than about 1/2 of the radius away from the edge of the pot, and no more than the length equal to the diameter away from the edge, to maximize water absorption. It is helpful to leave a space between plants on one side of the pot to make it easier to lift the lid and refill it as the plants grow larger. You can also use pots in raised beds and containers. Simply use the 1-radius rule to find out how large your containers and beds need to be.