10.000 year old Al-Ula.

View attachment 492250

You have nothing in your entire entity that is as old but as well kept as World UNESCO Heritage sites such as Mada'in Saleh or Petra.

Discovering Saudi Arabia's hidden archaeological treasures

Mada'in Saleh remains a blank page on the archaeological record, closed off by geography, politics, and religion – but this stunning region is about to throw open its doors to the world

Mada'in Saleh, the archaeological site with the Nabatean tomb from the first century ( All photographs by Nicholas Shakespeare )

Out of the windy darkness a fine sand was blowing across the road from Medina to Al-Ula. Flat desert on either side, a few lights. The Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta passed this way on camel back in 1326, and wrote of its emphatic wilderness: “He who enters it is lost and he who leaves it is born.”

Before mass tourism ruined them for a second time, I’d travelled to the so-called “lost” cities of

Petra, Machu Picchu and Angkor Wat. My destination tonight was the isolated sandstone valley eulogised by

Charles Doughty, the first European to enter it in 1876, as “the fabulous Mada’in Saleh which I was come from far countries to seek in Arabia”.

The prospect of following in Doughty’s flapping shadow gave me a jolt of anticipation that I hadn’t experienced since my twenties. Doughty’s classic book Arabia Deserta was championed by his friend TE Lawrence, who later used it as a military textbook, as the greatest record of adventure and

travel in our language.

It begins with Doughty trying to smuggle himself into Mada’in Saleh in the guise of a poor Syrian pilgrim. Even up until recently few Europeans have visited this cradle of forgotten civilisations, which, though designated a World Heritage Site in 2008, remains a blank page on the archaeological record, closed off by geography, politics, religion.

“Visitors last year from abroad? I can say zero,” my guide Ahmed tells me.

The temples of Mada'in Saleh near Al-Ula have survived for almost 3,000 years

This is set to change. Last July, under the impetus of

Saudi Arabia’s progressive new Crown Prince,

Mohammed Bin Salman, or “MBS” as he is popularly known, a Royal Commission took charge of Mada’in Saleh and its surrounds – “the crown jewel of a site that the country possesses,” says one of the archaeologists recruited to excavate it.

In December, public access was halted; first in order to survey what actually is there, next to develop a strategy for protecting it, and then to open up Mada’in Saleh to the outside world. My advance visit is aimed at providing an amuse-bouche, as it were.

In the bright morning sunlight, Ahmed escorts me through locked gates, past the German-built railway-line linking Damascus with Medina, which Lawrence bombed (“there are still local tribes which call their sons Al-Orans”), to the celebrated Nabatean rock tombs.

Doughty first heard about these in Petra, 300 miles north. Fifty years earlier, an awe-struck British naval commander had gazed in disbelief at Petra’s imperishable Treasury, murmuring, as many continue to do: “There is nothing in the world that resembles it.” He was wrong.

If a little less rosier than her sister city, Mada’in Saleh shares her capacity to stagger. Out of the flat desert, one after another, the ornate facades rise into sight, 111 of them, carved into perpendicular cliffs up to four storeys high, their low doorways decorated by Alexandrian masons in the first century AD, with Greek triangles, Roman pilasters, Arabian flowers, Egyptian sphinxes, birds.

“This is a twin to Petra,” Ahmed says. Except that in Petra we would be bobbing among crowds.

Tour guide Ahmed is descended from a long line of imams

Standing in reverent silence, with the valley to ourselves, I recall how the Victorian artist who supplied the first images of Petra to the world, David Roberts, responded to that other city. “I turned from it at length with an impression which will be effaced only by death.”

These tombs were carved for the Nabatean tribes who ruled this region for 300 years until the Romans annexed them in 106AD. Semi-nomadic pastoralists who had settled and grown wealthy, the Nabateans controlled the lucrative spice route from the Mediterranean to the Red Sea.

Then, like the civilisations they’d replaced, the Dedanites, the Lihyanites, the Thamuds, they galloped off into obscurity. Their tombs were looted: the acacia doors plundered for firewood, the marble statues melted to make lime for plaster, the porphyry urns smashed.

All that survives of their caravan city, Hegra, is a flat expanse behind a wire fence: “her clay-built streets are again the blown dust in the wilderness,” Doughty wrote.

Mada'in Saleh, the archaeological site with the Nabatean tomb from the first century

Nicholas Shakespear

10/12

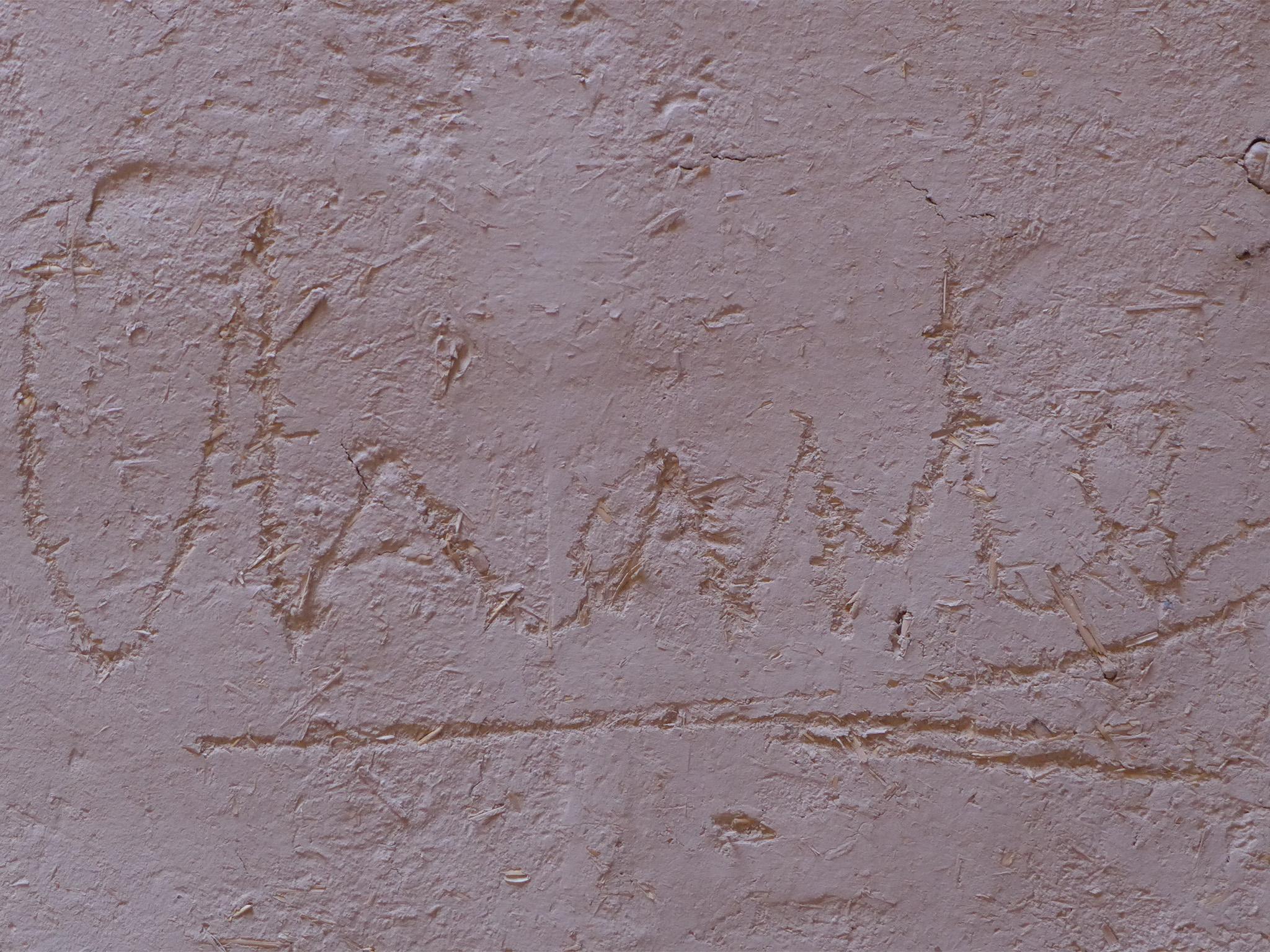

'Charles' is scratched on the oat-coloured mud wall not by Charles Doughty but by Prince Charles (in 2015, with his key)

Nicholas ShakespeareAl Gharamil

Below, a square hole in the rock floor denotes a sacrificial spot from the time of the Dedanites. Ahmed could be speaking of the cavity in the historical record when he says, “They were making sacrifices to one god, Dhu-Ghaibat, which means ‘the one who is absent’.”

Out in the desert, the wind has chiselled its own mysterious deities and hieroglyphs. The scene is stunning. In Petra, which forms part of the same massif, David Roberts threw away his pencil in despair at being able to convey it, believing that the ruins “sink into insignificance when compared with these stupendous rocks”.

It’s hard to disagree. Cliffs formed out of red and black sandstone have eroded into crazy, hallucinatory shapes: elephants, mushrooms, braying seals. If they were transcribed into music, it would be Wagnerian.

They make you believe in mountain gods, I tell Ahmed, who smiles. “I never try smoking weed, but when I hear someone react, I feel like that. It makes you high, naturally.”

For sheer high spirits, no one yields to the British archaeologist I meet that night. Jamie Quartermain is part of an international team employed since March to survey these sites.

A surveyor who pioneered the use of drones, Quartermain says: “We’ve been wanting to get involved here, but Saudi has been a closed shop, a completely untapped reserve."

"The perception is that it’s big, open desert. When I tried to find out anything about it, there was essentially one book. The discovery that there are so many archaeological sites is a big shock for most people. It was a big shock for me.”

Advised by the Royal Commission to expect 450 unexcavated sites, Quartermain estimates the truer number between 6,000-10,000. “The survival of the archaeology is remarkable, some of the best condition remains I’ve ever seen. We’re not finding it close to the surface, it’s above surface, well and truly visible.”

Ancient Dedan inscriptions. Holes in the rock floor denote a sacrificial spot from the time of the Dedanites

Deploying a drone, he has begun creating a three-dimensional textural surface of the area. Already, what he has found is ground-breaking. “You can see all the archaeology jumping out and biting you on the bottom.”

When, aged 20, I visited Petra, sleeping in one of the caves, I talked to the head of the Bdoul tribe, allegedly descendants of the Nabateans, who told me: “We have a saying that the more wealth you have, the more brain cells you need to be able to cope with it.

What impresses about MBS’s plan for Mada’in Saleh is his determination to use his nation’s resources to avoid the pitfalls of Petra.

“Wadi Rum is pretty disastrous,” says Chris Tuttle, an American archaeologist seconded to the project. Tuttle spent many years excavating in Petra. He saw at first hand the ruinous impact of tourism, both on the ruins and the local community.

By contrast, in Al-Ula, the local town for Mada’in Saleh, there has been a concerted drive to educate the locals, giving scholarships to 150 children, but also to attract experts armed with the latest methodol

One reason for the blankness on Saudi Arabia’s archaeological map, says Tuttle, has been the resistance of conservative religious leaders to question their history. “You don’t need to study the past when you’ve been given a manual from God.”

Suddenly, a multi-thousand-year-old story has become an open book, not a closed one, and the revelation it contains could be a complex of sites more significant even than Petra. My guide Ahmed Alimam is a perfect representative of Al-Ula’s past and future. He comes from a long line of imams descended from a grand tribal judge who arrived c1400 in Al Ula’s “old town”

Abandoned in 1983, the year of Ahmed’s birth, this haunting labyrinth of mud houses and twisting streets replaced Dedan and Hegra. It was built using stones from those cities. They can be seen fortifying the occasional doorway.

Ahmed leads the way down an empty street to the house where his parents used to live – collapsed beams, upturned crates. He shows me the mosque, erected over the spot where the Prophet Mohammed stopped in 630AD, and with a goat bone drew in the sand the direction of Medina; Ahmed’s uncle was the last imam.

And a modern inscription: the name “Charles”, scratched on the oat-coloured mud wall not, as momentarily I’d hoped, by Charles Doughty, but by Prince Charles (in 2015, with his key), and below it the Islamic translation.

During the Islamic period, Al-Ula, or El-Ally as Doughty knew it, became an important station on the haj road south, and marked the last place where Christians were permitted to travel. Ibn Battuta described how pilgrim caravans paused here for four days to resupply and wash, and to leave any excess baggage with the townspeople “who are known for their trustworthiness”.

“I hope we are still doing our best to be like that,” Ahmed says. “You can try, if you want, to leave something.”

The only thing I left behind after my four days here was an urge to come back.

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/...y-alhijir-petra-charles-doughty-a8373686.html

When KSA was inhabited by humans (first place outside of Africa) you country was a wasteland for 10.000's of years where only animals roamed.

To this very day you are 100's times more influenced by our ancestors and Arabs than vice versa.

WTF the joke that you are posting is not even a ziggurat but a freaking MOUND OR HILL!

Which is why it looks like a dump.

There are literally 10.000's of such in KSA and the most extensive ancient structures (seen from air) can be found in KSA.

Get lost from here, Arabized donkey.

One rock/camel graveyard in middle of desert is a joke compared to Iranian Civilizations.

Tehran

Settlement of Tehran dates back over 7,000 years.

[8] An important historical city in the area of modern-day Tehran, now absorbed by it, is known as "Rey", which is etymologically connected to the

Old Persian and

Avestan"Rhages".

[9] The city was a major area of the Iranian speaking

Medes and

Achaemenids.

In the Zoroastrian Avesta's

Videvdad (i, 15), Rhaga is mentioned as the twelfth sacred place created by

Ahura-Mazda.

[10] In the Old Persian inscriptions (

Behistun 2, 10–18), Rhaga appears as a province. From Rhaga,

Darius the Great sent reinforcements to his father

Hystaspes, who was putting down the rebellion in

Parthia (Behistun 3, 1–10).

[10]

Rey is richer than many other ancient cities in the number of its historical monuments, among which one might refer to the 3000-year-old Gebri castle, the 5000-year-old

Cheshmeh Ali hill, the 1000-year-old Bibi Shahr Banoo tomb and Shah Abbasi caravanserai. It has been home to pillars of science like

Rhazes.

The

Damavand mountain located near the city also appears in the

Shahnameh as the place where

Freydun bounds the dragon-fiend

Zahak. Damavand is important in

Persian mythological and legendary events.

[11]Kyumars, the Zoroastrian prototype of human beings and the first king in the Shahnameh, was said to have resided in Damavand.

[11] In these legends, the foundation of the city of Damavand was attributed to him.

[11] Arash the Archer, who sacrificed his body by giving all his strength to the arrow that demarcated Iran and

Turan, shot his arrow from Mount Damavand.

[11]This Persian legend was celebrated every year in the

Tiregan festival. A popular feast is reported to have been held in the city of Damavand on 7 Shawwal 1230, or in Gregorian calendar, 31 August 1815. During the alleged feast the people celebrated the anniversary of Zahak's death.

[11] In the Zoroastrian legends, the tyrant Zahak is to finally be killed by the Iranian hero

Garshaspbefore the final days.

[11]

In some Middle Persian texts, Rey is given as the birthplace of

Zoroaster,

[12] although modern historians generally place the birth of Zoroaster in

Khorasan. In one Persian tradition, the legendary king

Manuchehr was also born in Damavand.

[11]

There is also a shrine there, dedicated to commemorate Princess

Shahr Banu, eldestdaughter of the last ruler of the

Sassanid Empire. She gave birth to

Ali Zayn al Abidin(PBUH), the fourth holy Imam of the

ShiaIslam. This was through her marriage to

Hussain ibn Ali (PBUH), the grandson of prophet Muhammad (PBUH).

Tehran - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Rey, Iran - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Zagros (Kermanshah)

Signs of early agriculture date back as far as 9000 BC to the foothills of the Zagros Mountains,

[13] in cities later named

Anshanand

Susa.

Jarmo is one archaeological site in this area.

Shanidar, where the ancient skeletal remains of

Neanderthals have been found, is another.

Some of the earliest evidence of

wineproduction has been discovered in the Zagros Mountains; both the settlements of

Hajji Firuz Tepe and

Godin Tepe have given evidence of wine storage dating between 3500 and 5400 BC.

[14]

During early ancient times, the Zagros was the home of peoples such as the

Kassites,

Guti,

Assyrians,

Elamites and

Mitanni, who periodically invaded the

Sumerianand/or

Akkadian cities of

Mesopotamia. The mountains create a geographic barrier between the flatlands of Mesopotamia, which is in Iraq, and the Iranian plateau. A small archive of

clay tablets detailing the complex interactions of these groups in the early second millennium BC has been found at

Tell Shemshara along the

Little Zab.

[15] Tell Bazmusian, near Shemshara, was occupied between the sixth millennium BCE and the ninth century CE, although not continuously.

[16]

Zagros Mountains - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Kashan

Archeological discoveries in the

Sialk Hillocks which lie 4 km west of Kashan reveal that this region was one of the primary centers of

civilization in

pre-historic ages. Hence Kashan dates back to the

Elamite period of Iran. The

Sialk ziggurat still stands today in the suburbs of Kashan after 7,000 years.

The artifacts uncovered at

Sialk reside in

the Louvre in Paris and the

New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, and

Iran's National Museum.

Sialk, and the entire area around it, is thought to have first originated as a result of the pristine large water sources nearby that still run today. The Cheshmeh ye Soleiman (or "Solomon's Spring") has been bringing water to this area from nearby mountains for thousands of years.

By some accounts although not all Kashan was the origin of the

three wise men who followed the star that guided them to Bethlehem to witness the

nativity of Jesus, as recounted in the

Bible.

[3] Whatever the historical validity of this story, the attribution of Kashan as their original home testifies to the city's prestige at the time the story was set down.

Sultan Malik Shah I of the

Seljuk dynastyordered the building of a fortress in the middle of Kashan in the 11th century. The fortress walls, called

Ghal'eh Jalali still stand today in central Kashan.

Kashan was also a leisure vacation spot for

SafaviKings.

Bagh-e Fin (

Fin Garden), specifically, is one of the most famous gardens of Iran. This beautiful garden with its pool and orchards was designed for

Shah Abbas I as a classical

Persian vision of paradise. The original Safavid buildings have been substantially replaced and rebuilt by the

Qajar dynasty although the layout of trees and marble basins is close to the original. The garden itself however, was first founded 7000 years ago alongside the

Cheshmeh-ye-Soleiman. The garden is also notorious as the site of the murder of Mirza Taghi Khan known as

Amir Kabir, chancellor of

Nasser-al-Din Shah, Iran's King in 1852.

Kashan - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Tepe Sialk - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Chogha Mish

Tappeh-ye Choghā Mīsh (

Persian language; ČOḠĀ MĪŠ) dating back to

6800 BC, is the site of a

Chalcolithicsettlement in

Western Iran, located in the

Khuzistan Province on the Susiana Plain. It was occupied at the beginning of 6800 BC and continuously from the

Neolithicup to the

Proto-Literate period.

Musicians portrayed on pottery found at Chogha Mish

Chogha Mish was a regional center during the late

Uruk period of

Mesopotamia and is important today for information about the development of writing. At Chogha Mish, evidence begins with an accounting system using

clay tokens, over time changing to

clay tablets with marks, finally to the

cuneiformwriting system.

Chogha Mish - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Chogha Bonut - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Marhasi - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Haft Tepe - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Chogha Zanbil - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Signs of 9000-year-old settlement found in Iran's Behbahan

Lorestan

Lorestān bronze is a set of

Early Iron Agebronze artifacts of various individual forms which have been recovered from

Lorestān and

Kermanshah areas in west-central

Iran. They include a great number of weapons, ornaments, tools, and ceremonial objects. The artifacts were created by a major group of

Persianaboriginals known as

Lurs.

Lorestani Bronze objects were taken illegally to Europe via Mesopotamia and to cover up most of the items taken they called themMesopotamian while in fact there are no similarities what so ever between the Persian Bronze objects excavated in Lorestan 1943 to 1968, which were dated to be from

5000 BC. The hair pins and four men holding a cup were typical of that period which once again separates Iranian development from whatever was going on in so called Sumerian areas. Typical Lorestāni-style objects belong to the (Iranian)

Iron Age (c. 1250-650 BC).

The term "Lorestān bronze" is not normally used for earlier bronze artifacts from Luristan between the fourth millennium BC and the (Iranian)

Bronze Age (c. 2900-1250 BC). These bronze objects were similar to those found in

Mesopotamia and on the

Iranian plateau.

Swords and axes from Lorestān; on exhibit at the

Louvre Museum

Cave painting in Doushe cave, Lorestan, Iran, 8000 BC

In 1930 a large quantity of canonical Lorestān bronze artifacts appeared on the Iranian and European antiquities markets as a result of plundering of tombs in this region. Since 1938 several scientific excavations were conducted by American, Danish, British, Belgian, and Iranian archaeologists on the graveyards with stone tombs in the northern Pish Kuh valleys and the southern Pusht Kuh of Lorestān.

Lorestan Province - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Lorestān Bronze - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Zayandeh River (Ispahan)

Zayandeh River Culture (تمدن زاینده رود, literally "

Zāyandé-Rūd Civilization") is a hypothetical

pre-historic culture that is theorized to have flourished around the

Zayandeh River in Ispahan province of

Iran in 6,000

BC.

Archaeologists speculate that a possible early

civilizationexisted along the banks of the Zayandeh River, developing at the same time as other ancient civilizations appeared alongside rivers in the region.

Link with Sialk and Marvdasht civilizations

During the 2006 excavations, the

Iranianarchaeologistsuncovered some

artifacts that they linked to those from

Sialk and

Marvdasht.

[2]

Zayandeh River Culture - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Shahdad (Kerman)

Shahdad (

Persian: شهداد) is a city in and the capital of

Shahdad District, in

Kerman County,

Kerman Province,

Iran. At the 2006 census, its population was 4,097, in 1,010 families.

Shahdad is the centre of Shahdad district which includes smaller cities and villages such as Sirch,

Anduhjerd, Chehar Farsakh, Go-diz, Keshit, Ibrahim Abad, Joshan and Dehseif.

The driving distance from

Kermancity to Shahdad is 95 km. Shahdad is located at the edge of the

Lut desert. The local climate is hot and dry. The main agricultural produce is

datefruits.

Ancient bronze

flag, Shahdad

Kerman,

Iran

There are many

castles and

caravanserais at Shahdad and around. Examples are the Shafee Abaad castle and the Godeez castle. North of town the

Aratta civilization villageand dwarf humans are said to have existed since 6,000

BC. Sharain of emam Zadeh Zeyd, south of town, is the most respected religious site of Shahdad.

The oldest metal flag in human history was found in this city.

Shahdad - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Tepe Yahya

Tepe Yahya is an archaeological site in

Kermān Province,

Iran, some 220 km south of

Kerman city, 90 km south of

Baft city and 90 km south-west of

Jiroft.

Habitation spans the 6th to 2nd millennia BCE and the 10th to 4th centuries BCE. In the 3rd millennium BCE, the city was a production center of

chlorite pottery which were exported to

Mesopotamia. In this period, the area was under

Elamite influence, and tablets with

Proto-Elamite inscriptions were found.

[1]

The site is a circular mound, around 20 meters in height and around 187 meters in diameter.

[2] It was excavated in six seasons from 1967 to 1975 by the American School of Prehistoric Research of the

Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology of

Harvard University in a joint operation with what is now the

Shiraz University. The expedition was under the direction of C. C. Lamberg-Karlovsky.

Periodization is as follows:

Period I Sasanian pre: 200 BC-400 A.D.

Period II Achaemenian(?): 275-500 B.C.

Period III Iron Age: 500-1000 B.C.

Period IV A Elamite?: 2200-2500 B.C.

IV B Proto-Elamite: 2500-3000 B.C.

IV C Proto-Elamite: 3000-3400 B.C.

Period V Yahya Culture: 3400-3800 B.C.

Period VI Coarse Ware-Neolithic: 3800-4500 B.C.

Period VII: 4500-5500 B.C.

Tepe Yahya - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Susa

Susa (

ˈsuːsə/;

Persian: شوش

Shush;

[ʃuʃ];

Hebrew שׁוּשָׁן

Shushān;

Greek: Σοῦσα

[ˈsuːsa];

Syriac: ܫܘܫ

Shush;

Old Persian Çūšā) was an ancient city of the

Elamite,

First Persian Empire and

Parthianempires of

Iran. It is located in the lower

Zagros Mountains about 250 km (160 mi) east of the

Tigris River, between the

Karkheh and

Dez Rivers.

The modern Iranian town of

Shush is located at the site of ancient Susa.

Shush is the administrative capital of the

Shush County of Iran's

Khuzestan province. It had a population of 64,960 in 2005.

[1]

Map showing the area of the Elamite kingdom (in red) and the neighboring areas. The approximate

Bronze Age extension of the

Persian Gulf is shown.

In

historic literature, Susa appears in the very earliest Sumerian records: for example, it is described as one of the places obedient to

Inanna, patron deity of

Uruk, in

Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta.

Susa is also mentioned in the

Ketuvim of the

Hebrew Bibleby the name Shushan, mainly in

Esther, but also once each in

Nehemiah and

Daniel. Both Daniel and Nehemiah lived in Susa during the

Babylonian captivity of the 6th century BCE.

Esther became queen there, and saved the Jews from genocide. A tomb presumed to be that of Daniel is located in the area, known as

Shush-Daniel. The tomb is marked by an unusual white stone cone, which is neither regular nor symmetric. Many scholars believe it was at one point a

Star of David. Susa is further mentioned in the

Book of Jubilees (8:21 & 9:2) as one of the places within the inheritance of

Shem and his eldest son Elam; and in 8:1, "Susan" is also named as the son (or daughter, in some translations) of Elam.

Greek mythology attributed the founding of Susa to king

Memnon of

Aethiopia, a character from

Homer's

Trojan War epic, the

Iliad.

Proto-Elamite

In

urban history, Susa is one of the oldest-known settlements of the region. Based on C14 dating, the foundation of a settlement there occurred as early as 4395 BCE (a calibrated radio-carbon date).

[2] Archeologists have dated the first traces of an inhabited Neolithic village to c 7000 BCE. Evidence of a painted-pottery civilization has been dated to c 5000 BCE.

[3] Its name in

Elamite was written variously

Ŝuŝan,

Ŝuŝun, etc. The origin of the word

Susa is from the local city deity

Inshushinak. Like its

Chalcolithic neighbor

Uruk, Susa began as a discrete settlement in the

Susa I period (c 4000 BCE). Two settlements called

Acropolis (7 ha) and

Apadana (6.3 ha) by archeologists, would later merge to form Susa proper (18 ha).

[4] The Apadana was enclosed by 6m thick walls of

rammed earth. The founding of Susa corresponded with the abandonment of nearby villages. Potts suggests that the city may have been founded to try to reestablish the previously destroyed settlement at

Chogha Mish.

[4] Susa was firmly within the Uruk cultural sphere during the

Uruk period. An imitation of the entire state apparatus of Uruk,

proto-writing,

cylinder seals with Sumerian motifs, and monumental architecture, is found at Susa. Susa may have been a colony of Uruk. As such, the

periodization of Susa corresponds to Uruk; Early, Middle and Late

Susa II periods (3800–3100 BCE) correspond to Early, Middle, and Late Uruk periods.

By the middle

Susa II period, the city had grown to 25 ha.

[4]Susa III (3100–2900 BCE) corresponds with Uruk III period. Ambiguous reference to Elam (

Cuneiform; NIM) appear also in this period in Sumerian records. Susa enters history during the

Early Dynastic period of Sumer. A battle between

Kish and Susa is recorded in 2700 BCE.

Susa Cemetery

Shortly after Susa was first settled 6000 years ago, its inhabitants erected a temple on a monumental platform that rose over the flat surrounding landscape. The exceptional nature of the site is still recognizable today in the artistry of the ceramic vessels that were placed as offerings in a thousand or more graves near the base of the temple platform. Nearly two thousand pots were recovered from thecemetery most of them now in the

Louvre. The vessels found are eloquent testimony to the artistic and technical achievements of their makers, and they hold clues about the organization of the society that commissioned them.

[5] Painted ceramic vessels from Susa in the earliest first style are a late, regional version of the Mesopotamian

Ubaid ceramic tradition that spread across the Near East during the fifth millennium B.C.

[5]

Susa I style was very much a product of the past and of influences from contemporary ceramic industries in the mountains of western Iran. The recurrence in close association of vessels of three types—a drinking goblet or beaker, a serving dish, and a small jar—implies the consumption of three types of food, apparently thought to be as necessary for life in the afterworld as it is in this one. Ceramics of these shapes, which were painted, constitute a large proportion of the vessels from the cemetery. Others are course cooking-type jars and bowls with simple bands painted on them and were probably the grave goods of the sites of humbler citizens as well as adolescents and, perhaps, children.

[6] The pottery is carefully made by hand. Although a slow wheel may have been employed, the asymmetry of the vessels and the irregularity of the drawing of encircling lines and bands indicate that most of the work was done freehand.

Susa - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Elam - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://defence.pk/pdf/threads/ancient-iranian-civilizations-since-12000-years-ago.393162/

Which is why it looks like a dump.

Which is why it looks like a dump.