Mirzali Khan

SENIOR MEMBER

- Joined

- Sep 25, 2020

- Messages

- 5,855

- Reaction score

- -3

- Country

- Location

China would surely be more than happy to let the United States eliminate its enemies and incur the reputational costs from any civilian casualties.

by Rupert Stone

As the United States withdraws its remaining forces from Afghanistan, the Biden administration is scrambling to secure an “over the horizon” counterterrorism capability that would enable it to strike and surveil terrorist groups from a base outside the country.

Pakistan is one option for such a facility, given its proximity to the parts of Afghanistan where transnational terror groups such as Al Qaeda tend to reside. But its government has flatly rejected hosting U.S. forces, even though negotiations have reportedly taken place.

Pundits have assumed that China, Pakistan’s closest economic and security partner, would also oppose an American base due to its intensifying rivalry with the United States.

But that is far from guaranteed. The U.S.-Pakistan security partnership has served China’s interests over the years, so much so that Beijing even advised Islamabad to patch up its relations with Washington after the raid that killed Osama Bin Laden in 2011.

U.S. assistance bolsters a country that is not only vital to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) but also serves as a counterweight to India. China has nothing to gain from a Pakistan that is isolated and impoverished like Iran or North Korea.

When massive amounts of American aid poured into Pakistan after 9/11 in exchange for Islamabad’s support in the War on Terror, “Washington was resuming the role that Beijing wanted to see it play,” according to Andrew Small in his book, The China-Pakistan Axis.

Given the sharp deterioration in U.S.-China ties during the Trump administration, it is easy to forget that the two countries cooperated for years on counterterrorism in South Asia. Groups that threaten America, like Al Qaeda and Islamic State, also oppose China.

In a bid to enlist Beijing’s support in the War on Terror, Washington designated the anti-China Uyghur militant group ETIM as a terrorist organization in 2002. It subsequently killed numerous suspected ETIM fighters in airstrikes in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

China, for its part, has acquiesced to U.S.-led diplomatic initiatives. In 2018, Beijing surprised many observers by allowing the grey-listing of Pakistan at the Financial Action Task Force and the UN listing of Jaish-e-Mohammed chief, Masood Azhar, the following year.

But the recent souring of Sino-American ties has impaired collaboration. In 2020 the U.S. State Department rescinded ETIM’s terrorist designation. It is, therefore, hard to imagine American drones hitting ETIM targets anytime soon.

However, there are other anti-China terrorist groups in the region that the United States might strike, such as Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), also known as the Pakistani Taliban. TTP largely shelters in Afghanistan, near the Pakistani border.

SPONSORED CONTENT

While TTP and the Afghan Taliban share a similar ideology, they have different goals. The former targets the Pakistani state, the latter focuses on Afghanistan. Both groups have ties to Al Qaeda, according to the UN.

TTP was expelled from its base in the Pakistani tribal areas in 2014 and disintegrated. But it recently reunified under a new emir and is making a comeback. Attacks against Pakistani security forces have increased significantly in the last year.

TTP has repeatedly condemned China for its alleged mistreatment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang. Chinese personnel based in Pakistan have been killed and kidnapped by the group. In April, the Chinese ambassador narrowly avoided a TTP bombing at the Serena Hotel in Quetta.

It is doubtful that the ambassador was the intended target of the bomb. But the attack did demonstrate TTP’s operational capability, which managed to smuggle a vehicle laden with explosives into a heavily defended area.

It has also been reported that TTP is allying with Baloch nationalists in Pakistan. Baloch groups have repeatedly targeted China for its supposed exploitation of Balochistan’s resources through the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), part of the BRI.

The uptick in violence comes at a time when China is trying to turbo-charge its stalled CPEC initiative. Last year agreements were signed for new hydro-power projects in Pakistan. But a renewal of TTP terrorism could seriously undermine progress.

A U.S. base might therefore protect, not threaten, Chinese interests. While Pakistan has done much of the heavy-lifting fighting TTP in the past, U.S. drone strikes took out each one of the three emirs who preceded the current chief.

China would surely be more than happy to let the United States eliminate its enemies and incur the reputational costs from any civilian casualties. Washington is extremely unpopular in Pakistan and would likely remain so, distracting attention from China’s shortcomings.

Despite gushing talk of an “all-weather friendship,” Beijing’s standing in Pakistan is precarious. CPEC projects are expensive, and the two cultures are very different—one secular and modern, the other conservative and deeply religious.

Occasional scandals exemplify this rift. Last year, a Chinese official at the embassy in Islamabad caused outrage in Pakistan when he tweeted the image of a dancing, unveiled Uyghur women with the comment “Off your hijab.”

A continuing U.S. military footprint in the region would perpetuate the contrast Beijing and many Pakistanis like to draw between American belligerence and China’s purportedly peaceful, development-based approach to foreign relations.

If Pakistan agreed to host a U.S. facility, it could also benefit the country’s crisis-prone and Covid-19-stricken economy, facilitating access to funding from U.S.-controlled multilateral lending institutions such as the Asian Development Bank and World Bank.

It might also ease Islamabad’s relationship with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Pakistan secured a $6 billion bailout in 2019 and has reportedly managed to win U.S. support for delaying IMF-mandated reforms because of its help in Afghanistan.

Beijing has been more than happy to let the IMF pick up the tab for Pakistan’s recurrent economic crises. While China has periodically provided emergency financing, it would rather spread the risk than become Islamabad’s sole benefactor.

The nightmare scenario for Beijing would be a repeat of the 1990s, when the United States no longer relied on Pakistan for help in the anti-Soviet war in Afghanistan and could finally hit Islamabad with sanctions for nuclear proliferation.

In recent years, American politicians have encouraged the U.S. government to slap sanctions on Islamabad for state sponsorship of terrorism, but Pakistan has always been protected by the vital role it plays supporting the Afghan war effort.

If Washington had a base in Pakistan after its withdrawal from Afghanistan, that would prolong America’s dependency on Islamabad and preclude the kind of sanctions and isolation that would severely harm China’s interests.

Moreover, Pakistan could leverage its continuing cooperation with the United States to win a resumption of security assistance, suspended by Donald Trump in 2018, which would fortify the country’s defenses against an increasingly aggressive India.

China also has an interest in strengthening Pakistan’s hand against New Delhi and raising the costs of a two-front war, as its own rivalry with the South Asian giant intensified last year with a sudden and still-unresolved escalation of the Sino-Indian border dispute.

It is true that Pakistani prime minister Imran Khan has repeatedly opposed U.S. drone strikes and American military involvement in Pakistan, both before and after becoming prime minister. If such an agreement were made public, his political future would be in peril.

Furthermore, a base could galvanize terrorist groups, providing them with a powerful recruiting tool. Pakistan’s support for the U.S. War on Terror in the past generated violent hostility from militant organizations.

So, while there are benefits to China from a U.S. military presence in Pakistan, there are also risks. But it is wrong that Beijing would definitely veto an American base in the country. There are strong reasons to support it.

Rupert Stone is a freelance journalist working on issues related to South Asia and the Middle East. He has written for various publications, including Newsweek, VICE News, Al Jazeera, and The Independent.

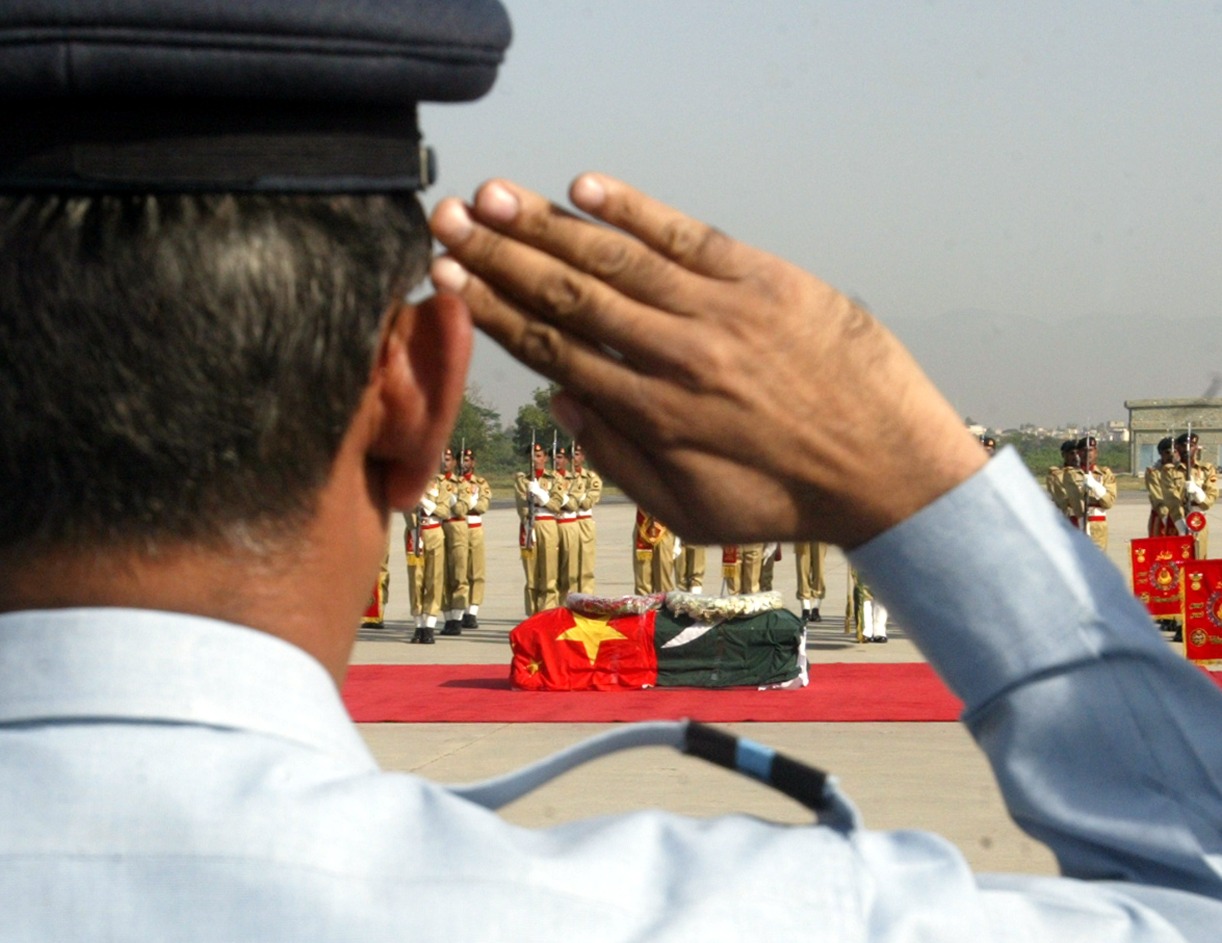

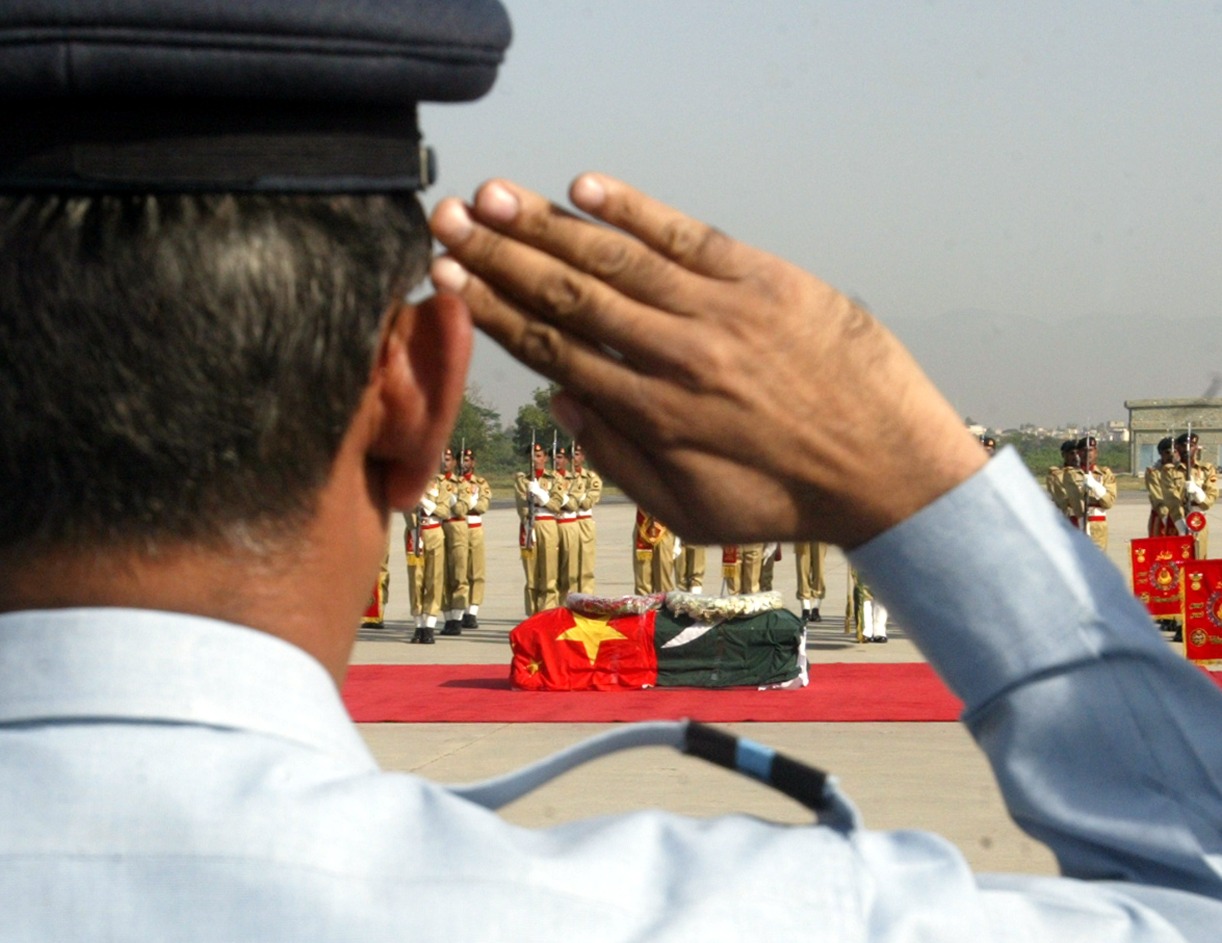

Image: A Pakistani Airforce soldier salutes the coffin of Chinese engineer Wang Peng during a ceremony at a military base in Rawalpindi October 16, 2004 before his body is to be flown to China. Peng, held hostage by al Qaeda-linked militants in Pakistan, was killed on Thursday but his colleague was rescued in a commando assault that killed their five kidnappers, officials said. Reuters/Mian Khursheed.

nationalinterest.org

nationalinterest.org

by Rupert Stone

As the United States withdraws its remaining forces from Afghanistan, the Biden administration is scrambling to secure an “over the horizon” counterterrorism capability that would enable it to strike and surveil terrorist groups from a base outside the country.

Pakistan is one option for such a facility, given its proximity to the parts of Afghanistan where transnational terror groups such as Al Qaeda tend to reside. But its government has flatly rejected hosting U.S. forces, even though negotiations have reportedly taken place.

Pundits have assumed that China, Pakistan’s closest economic and security partner, would also oppose an American base due to its intensifying rivalry with the United States.

But that is far from guaranteed. The U.S.-Pakistan security partnership has served China’s interests over the years, so much so that Beijing even advised Islamabad to patch up its relations with Washington after the raid that killed Osama Bin Laden in 2011.

U.S. assistance bolsters a country that is not only vital to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) but also serves as a counterweight to India. China has nothing to gain from a Pakistan that is isolated and impoverished like Iran or North Korea.

When massive amounts of American aid poured into Pakistan after 9/11 in exchange for Islamabad’s support in the War on Terror, “Washington was resuming the role that Beijing wanted to see it play,” according to Andrew Small in his book, The China-Pakistan Axis.

Given the sharp deterioration in U.S.-China ties during the Trump administration, it is easy to forget that the two countries cooperated for years on counterterrorism in South Asia. Groups that threaten America, like Al Qaeda and Islamic State, also oppose China.

In a bid to enlist Beijing’s support in the War on Terror, Washington designated the anti-China Uyghur militant group ETIM as a terrorist organization in 2002. It subsequently killed numerous suspected ETIM fighters in airstrikes in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

China, for its part, has acquiesced to U.S.-led diplomatic initiatives. In 2018, Beijing surprised many observers by allowing the grey-listing of Pakistan at the Financial Action Task Force and the UN listing of Jaish-e-Mohammed chief, Masood Azhar, the following year.

But the recent souring of Sino-American ties has impaired collaboration. In 2020 the U.S. State Department rescinded ETIM’s terrorist designation. It is, therefore, hard to imagine American drones hitting ETIM targets anytime soon.

However, there are other anti-China terrorist groups in the region that the United States might strike, such as Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), also known as the Pakistani Taliban. TTP largely shelters in Afghanistan, near the Pakistani border.

SPONSORED CONTENT

While TTP and the Afghan Taliban share a similar ideology, they have different goals. The former targets the Pakistani state, the latter focuses on Afghanistan. Both groups have ties to Al Qaeda, according to the UN.

TTP was expelled from its base in the Pakistani tribal areas in 2014 and disintegrated. But it recently reunified under a new emir and is making a comeback. Attacks against Pakistani security forces have increased significantly in the last year.

TTP has repeatedly condemned China for its alleged mistreatment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang. Chinese personnel based in Pakistan have been killed and kidnapped by the group. In April, the Chinese ambassador narrowly avoided a TTP bombing at the Serena Hotel in Quetta.

It is doubtful that the ambassador was the intended target of the bomb. But the attack did demonstrate TTP’s operational capability, which managed to smuggle a vehicle laden with explosives into a heavily defended area.

It has also been reported that TTP is allying with Baloch nationalists in Pakistan. Baloch groups have repeatedly targeted China for its supposed exploitation of Balochistan’s resources through the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), part of the BRI.

The uptick in violence comes at a time when China is trying to turbo-charge its stalled CPEC initiative. Last year agreements were signed for new hydro-power projects in Pakistan. But a renewal of TTP terrorism could seriously undermine progress.

A U.S. base might therefore protect, not threaten, Chinese interests. While Pakistan has done much of the heavy-lifting fighting TTP in the past, U.S. drone strikes took out each one of the three emirs who preceded the current chief.

China would surely be more than happy to let the United States eliminate its enemies and incur the reputational costs from any civilian casualties. Washington is extremely unpopular in Pakistan and would likely remain so, distracting attention from China’s shortcomings.

Despite gushing talk of an “all-weather friendship,” Beijing’s standing in Pakistan is precarious. CPEC projects are expensive, and the two cultures are very different—one secular and modern, the other conservative and deeply religious.

Occasional scandals exemplify this rift. Last year, a Chinese official at the embassy in Islamabad caused outrage in Pakistan when he tweeted the image of a dancing, unveiled Uyghur women with the comment “Off your hijab.”

A continuing U.S. military footprint in the region would perpetuate the contrast Beijing and many Pakistanis like to draw between American belligerence and China’s purportedly peaceful, development-based approach to foreign relations.

If Pakistan agreed to host a U.S. facility, it could also benefit the country’s crisis-prone and Covid-19-stricken economy, facilitating access to funding from U.S.-controlled multilateral lending institutions such as the Asian Development Bank and World Bank.

It might also ease Islamabad’s relationship with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Pakistan secured a $6 billion bailout in 2019 and has reportedly managed to win U.S. support for delaying IMF-mandated reforms because of its help in Afghanistan.

Beijing has been more than happy to let the IMF pick up the tab for Pakistan’s recurrent economic crises. While China has periodically provided emergency financing, it would rather spread the risk than become Islamabad’s sole benefactor.

The nightmare scenario for Beijing would be a repeat of the 1990s, when the United States no longer relied on Pakistan for help in the anti-Soviet war in Afghanistan and could finally hit Islamabad with sanctions for nuclear proliferation.

In recent years, American politicians have encouraged the U.S. government to slap sanctions on Islamabad for state sponsorship of terrorism, but Pakistan has always been protected by the vital role it plays supporting the Afghan war effort.

If Washington had a base in Pakistan after its withdrawal from Afghanistan, that would prolong America’s dependency on Islamabad and preclude the kind of sanctions and isolation that would severely harm China’s interests.

Moreover, Pakistan could leverage its continuing cooperation with the United States to win a resumption of security assistance, suspended by Donald Trump in 2018, which would fortify the country’s defenses against an increasingly aggressive India.

China also has an interest in strengthening Pakistan’s hand against New Delhi and raising the costs of a two-front war, as its own rivalry with the South Asian giant intensified last year with a sudden and still-unresolved escalation of the Sino-Indian border dispute.

It is true that Pakistani prime minister Imran Khan has repeatedly opposed U.S. drone strikes and American military involvement in Pakistan, both before and after becoming prime minister. If such an agreement were made public, his political future would be in peril.

Furthermore, a base could galvanize terrorist groups, providing them with a powerful recruiting tool. Pakistan’s support for the U.S. War on Terror in the past generated violent hostility from militant organizations.

So, while there are benefits to China from a U.S. military presence in Pakistan, there are also risks. But it is wrong that Beijing would definitely veto an American base in the country. There are strong reasons to support it.

Rupert Stone is a freelance journalist working on issues related to South Asia and the Middle East. He has written for various publications, including Newsweek, VICE News, Al Jazeera, and The Independent.

Image: A Pakistani Airforce soldier salutes the coffin of Chinese engineer Wang Peng during a ceremony at a military base in Rawalpindi October 16, 2004 before his body is to be flown to China. Peng, held hostage by al Qaeda-linked militants in Pakistan, was killed on Thursday but his colleague was rescued in a commando assault that killed their five kidnappers, officials said. Reuters/Mian Khursheed.

How a U.S. Base in Pakistan Serves China’s Interests

China would surely be more than happy to let the United States eliminate its enemies and incur the reputational costs from any civilian casualties.