خره مينه لګته وي

FULL MEMBER

- Joined

- Jul 7, 2014

- Messages

- 1,767

- Reaction score

- 0

- Country

- Location

let me warn you all before you start reading, it's a very long article..if you are not used to reading long articles then skip this piece of writing...

How land authorities and Bahria Town (Pvt) Ltd colluded in violating

KARACHI: There’s Bollywood music blaring from somewhere. The tables at an outdoor tea stall are packed and waiters rush back and forth with steaming cups in hand. A corncob seller does brisk business at his pushcart. The street is full of cars and people. Every evening, this section of Tauheed Commercial in Defence Housing Authority Phase V throbs with activity, with the anticipation of making an overnight profit.

It is a casino of sorts – except that instead of roulette and blackjack, it is a game of real estate that is creating the buzz. The name of that real estate: Bahria Town Karachi (BTK), a sprawling, upmarket gated community being constructed off the Super Highway in the outer reaches of Pakistan’s largest city.

Scores of real estate agencies line two or three streets in Tauheed Commercial, almost all of them emblazoned with the Bahria Town Ltd logo. Many among them are authorised dealers for Bahria Town real estate.

“A 125-square yard space in Midway Commercial has gone up by Rs.9 million in the two years since it came on the market,” said an agent about investment prospects in BTK. “In two years, I guarantee you, it’ll be Rs.80m.”

Another gleefully says that “there is almost no plot left unsold, even in the recently announced Sports City [a neighbourhood within BTK]”. Incidentally, one of these real estate agencies, run by two brothers, is also known for its very large hawala transactions for specific clients.

Even the registration forms for new projects in BTK are big business. According to a land official, “Each form can sell for over Rs.100,000, generating billions in sale and trade of the registration forms alone.”

The multibillion-rupee enterprise known as Bahria Town Karachi depends for its success on the brazen manipulation of the law by the political elite and land officials who, hand-in-glove with influential figures in the establishment, are using the state’s coercive powers to deprive rightful owners of their land.

To add insult to injury, all this skullduggery is being packaged as ‘development’.

______________________________________________________________________________

Land authorities and Bahria Town (Pvt) Ltd have colluded in violating multiple laws to facilitate a massive land grab in Pakistan’s largest city.

______________________________________________________________________________

On March 19, around midday, several police mobiles led by Inspector Khan Nawaz surrounded Juma Morio goth, a small village of about 250 houses in deh Langheji, district Malir, about 13 kilometres north of the Super Highway. They were accompanied by bulldozers, wheel loaders and dump trucks.

Their objective: to demolish a number of huts and make way for a Bahria Town road through the village. “The job was quickly completed and the rubble hauled away while hapless villagers looked on in a daze, knowing full well there will be no justice for them,” said Ameer Ali, one of the residents.

Another view of BTK’s grand entrance.

Just two days earlier, the villagers had expressed their fears to Dawn that they would soon be forced from their land.

“The police have been arresting our people, threatening them that they’ll show their arrest as being from places such as Wana, Mastung or Kalat,” said Kanda Khan Gabol. “They took me into custody for several hours and only let me go when a crowd gathered and it seemed as if the highway would be closed down.”

The problems for the villagers began on Feb 9, when they had resisted the first attempt by personnel from Bahria Town and the Malir Development Authority (MDA) – accompanied by a large contingent of police and bulldozers – to have the way cleared for a road through Juma Morio.

In response, MDA officials lodged an FIR in which they accused Kanda Khan Gabol, Ameer Ali and a dozen other villagers of firing at them.

Even though the challan did not furnish, amongst other things, any proof of MDA’s ownership of the land in question, Judge Sher Muhammad Kolachi ordered the inclusion of Section 6(2)C(L)(M) of the Anti-Terrorism Act 1997 in the criminally defective FIR.

Many of the accused remain on the run and that was the reason, villagers claim, they were unable to resist the March 19 demolition.

A view of Jinnah Avenue, one of BTK’s main MDA-financed thoroughfares.

Juma Morio is only the latest village to have fallen victim to such tactics to grab communal land that has been home to families since generations.

Villages in the surrounding area of district Malir are rife with similar accounts of residents being harassed and intimidated into selling or abandoning their land.

Despite the fact that many have land documents to prove their claims of possession, as well as agricultural leases to till the land, resistance is ruthlessly countered. Homes have been levelled, graveyards obliterated, fruit trees uprooted, and tube wells smashed.

Late one night in November last year, a number of police mobiles and APCs descended on Ali Mohammed Gabol goth. Breaking into the homes of sleeping residents, policemen hauled off five villagers – Din Mohammed, Abbas, Iqbal, Punno and Dadullah – in their vehicles. “Not only that, along with money, jewelry and other belongings, they also took away three goats,” said Mohammed Musa. “That was a kind of warning that next time they would cart away our women as well.”

The raid was the sequel to events of a few days earlier when a police contingent, also led by Inspector Khan Nawaz, had surrounded the village to force them to vacate the land for a road to be constructed through it, which the villagers had refused to do.

Police personnel oversee the beginning of construction work to counter resistance by villagers.

Instead, they filed a petition in the Sindh High Court (SHC), pleading that MDA, Bahria, and police be restrained from “interfering, encroaching upon, harassing or blackmailing the petitioners, their families and dispossessing them from their lawful possession of their land”.

According to their families, Malir police would not give them any information about the detained men’s whereabouts when they went to the police station in the morning. In desperation they turned to the local PPP representatives, who told them that the price for the missing men’s freedom was to give up their land. “What choice did we have except to surrender?” asked one of the villagers.

Faiz Mohammed Gabol (third from left) watches as work proceeds on land where his orchards used to be.

Gul Hasan Kalmati, a local historian and chronicler asked in anguish: “According to what law is this opulent complex being constructed for well-to-do-people at the cost of local residents’ ruin and displacement? Is this how the PPP rewards its loyal voters?”

Crushed under BTK’s massive footprint

Juma Morio and Ali Mohammed Gabol are among at least 45 goths (villages) that fall within the areas of four dehs of former Gadap Town that are now part of district Malir, and are being affected one way or another by the construction of BTK.

These hamlets are home to people who in many cases have lived on these collectively owned spaces since well over a century: their graveyards and shrines are testament to their ancient, customary right to the land.

Malir, which measures 2,557 square kilometres or 631,848 acres, is Karachi’s largest district. Much of it comprises agricultural land, nullahs, hills and wildlife sanctuaries, including parts of Kirthar National Park. Agriculture, poultry farming and livestock rearing bring in meager earnings that are shared amongst goth residents.

Needless to say, their voices have no currency with the elite, and there are few government facilities provided to them.

Many of the goths have not been regularised – that is, they are as yet not sanctioned under the Goth Abad Scheme – a status that can confer distinct advantages.

“Regularisation gives goth residents land title, which means they can’t be evicted as before,” said Anwar Rashid, director of the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP). “Even if developers use strong-arm tactics, regularisation means that the cost of the land increases ten-fold, sometimes even more.”

A wheel loader tears down rows of date palms.

Since 2006, until her murder in 2013, Perween Rahman, the then OPP director and ardent defender of Karachi’s resources and its marginalised millions’ right to basic services, had started to painstakingly document the manygoths in Karachi, including those in Gadap, with the help of OPP staff (Documentation is invaluable, for it is the first step in the process of getting goths regularised.)

“Development doesn’t come from concrete!” she would often say. “It comes from human development.”

Until Ms Rahman’s death, the OPP team had managed to document 1,131goths in Karachi, out of which 817 were in Gadap alone, where BTK continues to expand. Of the Gadap villages, 518 have so far been regularised. Since Ms Rahman’s death however, that process has come to a standstill.

And that suits the preferred modus operandi of ‘developers’ very well. When unregularised goths come in their way, they have the residents evicted wholesale from the land, at the most with a pittance as ‘compensation’.

Never before, however, has there been a residential complex quite like the mammoth BTK being constructed by the company that is owned by the redoubtable Malik Riaz.

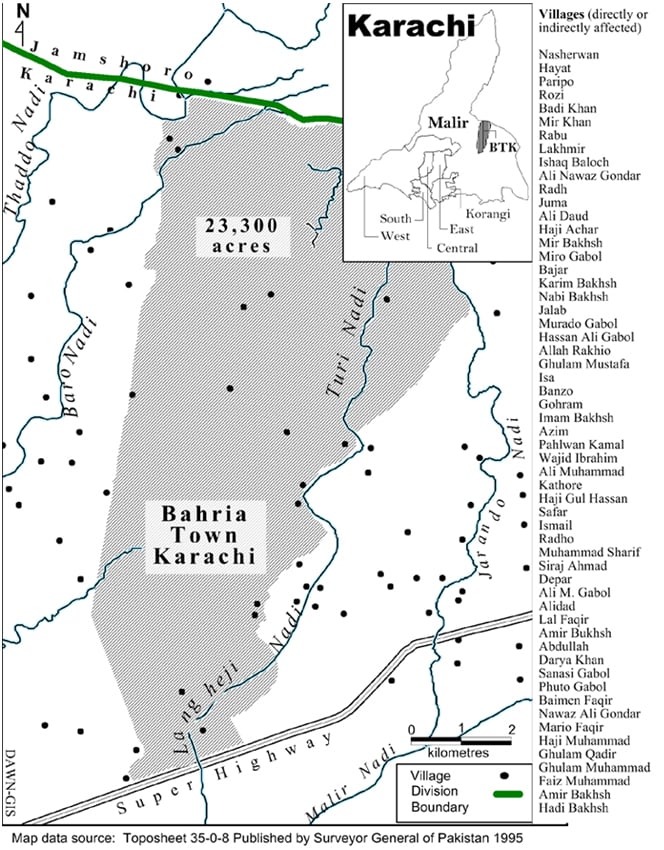

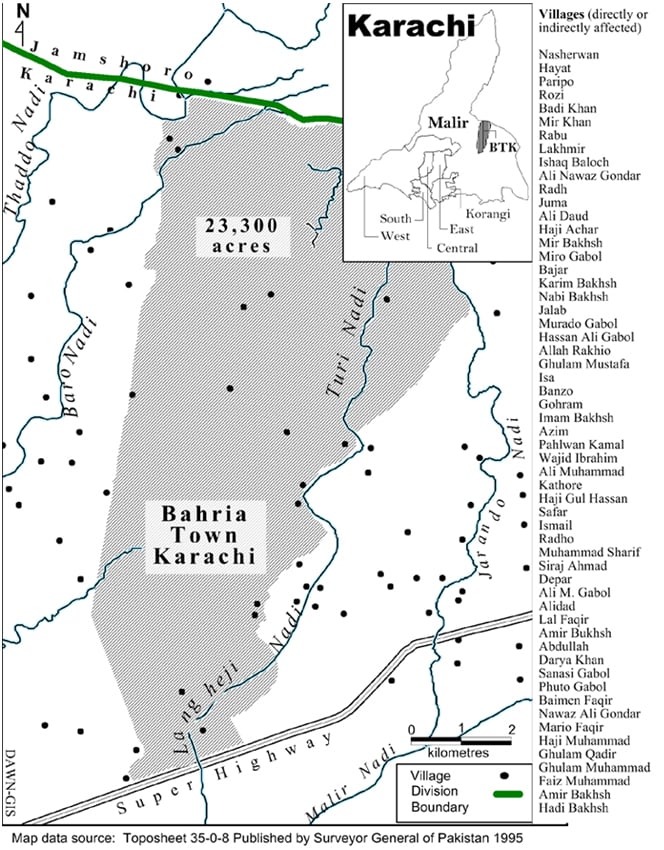

Physical GPS surveys by Dawn, using Bahria’s on-site markers as a guide – as well as interviews with locals – reveal that at present, BTK sprawls across more than 93 sq kms or 23,300 acres (see map).

Map showing villages directly or indirectly affected by development.

However, the company has purchased only 7,631 acres in Karachi from private parties – as per statements given to Dawn last year by a senior official from Bahria, Colonel (retired) Khalilur Rehman, as well as a legal aide to Mr Riaz.

Even this claim, as this story will demonstrate, is patently false as this area is only held through a special power of attorney.

There was no response by Bahria to questions put to it by Dawn about BTK or to the subsequent reminder.

Located just off the Super Highway, 9kms beyond Toll Plaza, the complex’s wide thoroughfares, generously proportioned residential schemes, commercial belts, 36-hole international standard golf course and the world’s seventh largest mosque promise a utopian existence away from the urban jungle of Karachi proper.

Flagrant violations of the law

Unethical and inhumane as it is, driving residents out of goths is only one aspect of the story behind BTK’s massive footprint on the outskirts of the city.

Police officials provide muscle power for the forcible takeover of land belonging

to the villagers.

The following is an exposé of how the powers that be, as well as corrupt officials from the Board of Revenue (BoR) Sindh, MDA, the district administration and police have all colluded with Bahria in various ways to make a colossal fortune off government land.

BoR Sindh is the original custodian of all land in the province. Besides collecting revenue and maintaining land records, it is the conduit for allotment of land to individuals, societies and various institutions and development agencies, such as the Karachi Development Authority, Defence Housing Authority Karachi, MDA, etc to develop schemes for specific purposes.

MDA – whose chairman during 2014 and 2015 was Sharjeel Inam Memon by virtue of being minister for local government and rural development – was set up for the purpose of developing land allotted to it by BoR Sindh in district Malir.

Legally, MDA – as per the Malir Development Authority Act 1993 under which it functions – cannot hand over to private developers any land that has been entrusted to it for specific purposes.

The aforementioned law repeatedly reiterates that MDA’s schemes are meant for the “socio-economic upliftment” of the “people of that area”.

How land authorities and Bahria Town (Pvt) Ltd colluded in violating

multiple laws to facilitate a massive land grab.

It is a casino of sorts – except that instead of roulette and blackjack, it is a game of real estate that is creating the buzz. The name of that real estate: Bahria Town Karachi (BTK), a sprawling, upmarket gated community being constructed off the Super Highway in the outer reaches of Pakistan’s largest city.

Scores of real estate agencies line two or three streets in Tauheed Commercial, almost all of them emblazoned with the Bahria Town Ltd logo. Many among them are authorised dealers for Bahria Town real estate.

“A 125-square yard space in Midway Commercial has gone up by Rs.9 million in the two years since it came on the market,” said an agent about investment prospects in BTK. “In two years, I guarantee you, it’ll be Rs.80m.”

Another gleefully says that “there is almost no plot left unsold, even in the recently announced Sports City [a neighbourhood within BTK]”. Incidentally, one of these real estate agencies, run by two brothers, is also known for its very large hawala transactions for specific clients.

Even the registration forms for new projects in BTK are big business. According to a land official, “Each form can sell for over Rs.100,000, generating billions in sale and trade of the registration forms alone.”

The multibillion-rupee enterprise known as Bahria Town Karachi depends for its success on the brazen manipulation of the law by the political elite and land officials who, hand-in-glove with influential figures in the establishment, are using the state’s coercive powers to deprive rightful owners of their land.

To add insult to injury, all this skullduggery is being packaged as ‘development’.

______________________________________________________________________________

Land authorities and Bahria Town (Pvt) Ltd have colluded in violating multiple laws to facilitate a massive land grab in Pakistan’s largest city.

______________________________________________________________________________

On March 19, around midday, several police mobiles led by Inspector Khan Nawaz surrounded Juma Morio goth, a small village of about 250 houses in deh Langheji, district Malir, about 13 kilometres north of the Super Highway. They were accompanied by bulldozers, wheel loaders and dump trucks.

Their objective: to demolish a number of huts and make way for a Bahria Town road through the village. “The job was quickly completed and the rubble hauled away while hapless villagers looked on in a daze, knowing full well there will be no justice for them,” said Ameer Ali, one of the residents.

Another view of BTK’s grand entrance.

Just two days earlier, the villagers had expressed their fears to Dawn that they would soon be forced from their land.

“The police have been arresting our people, threatening them that they’ll show their arrest as being from places such as Wana, Mastung or Kalat,” said Kanda Khan Gabol. “They took me into custody for several hours and only let me go when a crowd gathered and it seemed as if the highway would be closed down.”

The problems for the villagers began on Feb 9, when they had resisted the first attempt by personnel from Bahria Town and the Malir Development Authority (MDA) – accompanied by a large contingent of police and bulldozers – to have the way cleared for a road through Juma Morio.

In response, MDA officials lodged an FIR in which they accused Kanda Khan Gabol, Ameer Ali and a dozen other villagers of firing at them.

Even though the challan did not furnish, amongst other things, any proof of MDA’s ownership of the land in question, Judge Sher Muhammad Kolachi ordered the inclusion of Section 6(2)C(L)(M) of the Anti-Terrorism Act 1997 in the criminally defective FIR.

Many of the accused remain on the run and that was the reason, villagers claim, they were unable to resist the March 19 demolition.

A view of Jinnah Avenue, one of BTK’s main MDA-financed thoroughfares.

Juma Morio is only the latest village to have fallen victim to such tactics to grab communal land that has been home to families since generations.

Villages in the surrounding area of district Malir are rife with similar accounts of residents being harassed and intimidated into selling or abandoning their land.

Despite the fact that many have land documents to prove their claims of possession, as well as agricultural leases to till the land, resistance is ruthlessly countered. Homes have been levelled, graveyards obliterated, fruit trees uprooted, and tube wells smashed.

Late one night in November last year, a number of police mobiles and APCs descended on Ali Mohammed Gabol goth. Breaking into the homes of sleeping residents, policemen hauled off five villagers – Din Mohammed, Abbas, Iqbal, Punno and Dadullah – in their vehicles. “Not only that, along with money, jewelry and other belongings, they also took away three goats,” said Mohammed Musa. “That was a kind of warning that next time they would cart away our women as well.”

The raid was the sequel to events of a few days earlier when a police contingent, also led by Inspector Khan Nawaz, had surrounded the village to force them to vacate the land for a road to be constructed through it, which the villagers had refused to do.

Police personnel oversee the beginning of construction work to counter resistance by villagers.

Instead, they filed a petition in the Sindh High Court (SHC), pleading that MDA, Bahria, and police be restrained from “interfering, encroaching upon, harassing or blackmailing the petitioners, their families and dispossessing them from their lawful possession of their land”.

According to their families, Malir police would not give them any information about the detained men’s whereabouts when they went to the police station in the morning. In desperation they turned to the local PPP representatives, who told them that the price for the missing men’s freedom was to give up their land. “What choice did we have except to surrender?” asked one of the villagers.

Faiz Mohammed Gabol (third from left) watches as work proceeds on land where his orchards used to be.

Gul Hasan Kalmati, a local historian and chronicler asked in anguish: “According to what law is this opulent complex being constructed for well-to-do-people at the cost of local residents’ ruin and displacement? Is this how the PPP rewards its loyal voters?”

Crushed under BTK’s massive footprint

Juma Morio and Ali Mohammed Gabol are among at least 45 goths (villages) that fall within the areas of four dehs of former Gadap Town that are now part of district Malir, and are being affected one way or another by the construction of BTK.

These hamlets are home to people who in many cases have lived on these collectively owned spaces since well over a century: their graveyards and shrines are testament to their ancient, customary right to the land.

Malir, which measures 2,557 square kilometres or 631,848 acres, is Karachi’s largest district. Much of it comprises agricultural land, nullahs, hills and wildlife sanctuaries, including parts of Kirthar National Park. Agriculture, poultry farming and livestock rearing bring in meager earnings that are shared amongst goth residents.

Needless to say, their voices have no currency with the elite, and there are few government facilities provided to them.

Many of the goths have not been regularised – that is, they are as yet not sanctioned under the Goth Abad Scheme – a status that can confer distinct advantages.

“Regularisation gives goth residents land title, which means they can’t be evicted as before,” said Anwar Rashid, director of the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP). “Even if developers use strong-arm tactics, regularisation means that the cost of the land increases ten-fold, sometimes even more.”

A wheel loader tears down rows of date palms.

Since 2006, until her murder in 2013, Perween Rahman, the then OPP director and ardent defender of Karachi’s resources and its marginalised millions’ right to basic services, had started to painstakingly document the manygoths in Karachi, including those in Gadap, with the help of OPP staff (Documentation is invaluable, for it is the first step in the process of getting goths regularised.)

“Development doesn’t come from concrete!” she would often say. “It comes from human development.”

Until Ms Rahman’s death, the OPP team had managed to document 1,131goths in Karachi, out of which 817 were in Gadap alone, where BTK continues to expand. Of the Gadap villages, 518 have so far been regularised. Since Ms Rahman’s death however, that process has come to a standstill.

And that suits the preferred modus operandi of ‘developers’ very well. When unregularised goths come in their way, they have the residents evicted wholesale from the land, at the most with a pittance as ‘compensation’.

Never before, however, has there been a residential complex quite like the mammoth BTK being constructed by the company that is owned by the redoubtable Malik Riaz.

Physical GPS surveys by Dawn, using Bahria’s on-site markers as a guide – as well as interviews with locals – reveal that at present, BTK sprawls across more than 93 sq kms or 23,300 acres (see map).

Map showing villages directly or indirectly affected by development.

However, the company has purchased only 7,631 acres in Karachi from private parties – as per statements given to Dawn last year by a senior official from Bahria, Colonel (retired) Khalilur Rehman, as well as a legal aide to Mr Riaz.

Even this claim, as this story will demonstrate, is patently false as this area is only held through a special power of attorney.

There was no response by Bahria to questions put to it by Dawn about BTK or to the subsequent reminder.

Located just off the Super Highway, 9kms beyond Toll Plaza, the complex’s wide thoroughfares, generously proportioned residential schemes, commercial belts, 36-hole international standard golf course and the world’s seventh largest mosque promise a utopian existence away from the urban jungle of Karachi proper.

Flagrant violations of the law

Unethical and inhumane as it is, driving residents out of goths is only one aspect of the story behind BTK’s massive footprint on the outskirts of the city.

Police officials provide muscle power for the forcible takeover of land belonging

to the villagers.

The following is an exposé of how the powers that be, as well as corrupt officials from the Board of Revenue (BoR) Sindh, MDA, the district administration and police have all colluded with Bahria in various ways to make a colossal fortune off government land.

BoR Sindh is the original custodian of all land in the province. Besides collecting revenue and maintaining land records, it is the conduit for allotment of land to individuals, societies and various institutions and development agencies, such as the Karachi Development Authority, Defence Housing Authority Karachi, MDA, etc to develop schemes for specific purposes.

MDA – whose chairman during 2014 and 2015 was Sharjeel Inam Memon by virtue of being minister for local government and rural development – was set up for the purpose of developing land allotted to it by BoR Sindh in district Malir.

Legally, MDA – as per the Malir Development Authority Act 1993 under which it functions – cannot hand over to private developers any land that has been entrusted to it for specific purposes.

The aforementioned law repeatedly reiterates that MDA’s schemes are meant for the “socio-economic upliftment” of the “people of that area”.