H!TchHiker

SENIOR MEMBER

- Joined

- Aug 16, 2016

- Messages

- 4,765

- Reaction score

- 8

- Country

- Location

https://tribune.com.pk/story/1585305/1-tales-survivors-1971-war-ordeal-non-bengalis/

Commenting on the Bangladesh government’s claim that three million Bengalis were killed during the military operation that Pakistan Army started in March 1971, Sarmila Bose in her ‘Death Reckoning’ writes that history of Bangladesh is the history written by the victors of war.

While falsifying the highly exaggerated Bangladeshi and Indian claims about the deaths of Bengalis, Bose in her monumental work on the 1971 war notes that the only group whose killing could qualify the definition of genocide were non-Bengali residents of East Pakistan.

According to the whitepaper published in March 1971, around one hundred thousand non-Bengalis were killed in various parts of East Pakistan till that time. However, the later estimates based on the post-April counting suggest that the total number of non-Bengalis killed by Mukti Bahini was around two hundred and fifty thousand.

While sporadic killing of non-Bengalis took place all across the former East Pakistan, their mass massacres took place particularly in Jessore, Isherdee, Chandragona Paper Mills of Chittagong, Admajee Jute Mills of Narayanganj and Santahar of Rashahi. In remembrance of the martyrs of these massacres, The Express Tribune presents accounts of a few survivors.

How Mukti Bahini ‘cleansed’ Santahar of non-Bengalis

Haji Ehsanullah was 19 years old when his neighbourhood in Loco West was attacked by a Bengali mob on March 26. He says he along with his father, mother and wife jumped into a relative’s house and hid in a bathroom.

“When the attackers were gone, we first went to a graveyard and spend the night there. The coming days were spent in Ghorahaat, Santahar Railway Station and Station Colony,” he adds.

Ehsanullah remembers how on the morning of April 17, the Mukti Bahini launched its final assault against the unarmed residents of the colony.

“When the attack started, my parents asked me to run away. I covered my face with a kerchief and went out holding a metal rod in my hand,” he says, adding that the massacre was in full swing and he saw Bengali men throwing little children into the adjoining pond. “I was also stopped by a group of Bengalis who wanted to kill me, but a man, Aakaash, intervened and said that he knew me and that I was a Bengali.”

He says Aakaash’s colleagues were not much convinced and one of the group members gave me a shovel to dig out a grave. “I started digging a ditch while my people were being killed. I frantically kept digging.”

Ehsanullah says the same Bengali, Aakaash, again came to him in the afternoon, offered him some food and gave him address of his sister, who lived in the town of Ontahar.

Ehsanullah says he somehow managed to get to that place, where he was given refuge until arrival of Pakistan Army on April 22. “When I returned to Santahar, in search of my family, I could not find my parents, but my wife was alive. The killers had slit her neck but she had survived as the wound was not deep enough,” he adds.

Dr Jameel Akhtar, who now lives in Shah Faisal Colony of Karachi, says his entire family – comprising his parents and 10 siblings – was killed in the April 16 massacre at Railway Colony.

“I was among the youngest kids of my parents. When the attack started at around 4am, we hugged each other. But my parent asked me to escape and clad me in a lungi and vest. My mother also gave me her gold jewellery which I hid in a fold in my lungi.”

Dr Jameel says when the attackers reached their house, his elder brother opened the door. “I was standing behind him. I saw them killing my brother right in front of my eyes.”

He says he ran out from the backside of his house. “I rushed to the railway station but saw a Bengali railway officer, Jalal Guard, prowling there with a spear in his hand. I ran from there but I soon found myself in front of another group of killers.”

Dr Jameel says he tried to convince the Mukti Bahini men that he was also a Bengali but they did not believe him. “They were about to hit me when I had an idea. I brought out the jewellery from my lungi and threw it in front of them. The killers instantly started vying for the gold, giving me an opportunity to escape.”

Forgotten pages: The martyrs of Naogaon Cantonment

Dr Jameel says he then started moving towards Naogaon. “But on that way, I encountered with another group of killers who had put on display half a dozen human heads. They asked me who I was. I told them that I am a Bengali. The asked me as to what was the slogan for that day. On my way, I had seen a slogan written on the walls. I told them it’s ‘Amar Desh, Tumar Desh, Bangladesh, Bangladesh’. I was fortunate, they let me go,” he says.

Bilquis, who now lives in Karachi’s Orangi Town, was a married woman with three children in 1971. She says when the Bengalis started attacking different neighbourhoods, her husband decided to move along with the family to the factory of Gramophone beri-wala.

“Here the hooligans of Mukti Bahini came and picked up men who were often slaughtered outside the factory. My husband was also among those who was killed outside that premises,” she reminisces.

Bilquis says despite all the killings in and outside the factory, she and her family remained in that building until April 17 when Bengalis asked them to move to the Railway Colony.

“I along with other women was being driven to the station when a Bengali man, who knew my husband and called me her sister, came to me and told me in whispers that I should not go to the station as all people were being killed there,” she says.

“The other Bengalis were not ready at first to allow me to go with him but he somehow managed to convince them. He later took me to his family, who gave refuge to me.”

Bilquis says the other women who had left the factory with her were brought to a pond where they were slaughtered. “I was, however, fortunate that I remained safe and also found my children alive,” she adds.

Irfan Ulllah Siddiqui was a little kid when his family was massacred in the Station Colony on April 17.

“My family comprised my parents, six daughters and three brothers. All of them were killed. I was 6-year-old at that time and managed to survive as I hid beneath the bodies of my family members,” he recalls, adding that it was many days after the massacre that he was discovered by her aunt who lived in Saidpur and had come in search of survivors of her family.

Muhammad Qurban, who now lives in Karachi’s Malir area, was 19 years old in March 1971. He was among the people who buried the victims of the March 27 killing at Chaibagan Mosque.

“My family had moved to the railway station after this attack. However, on April 2, I left the station and somehow reached Naogaon,” he recalls, adding that he stayed at Naogaon until the arrival of the Pakistan Army.

“When I returned to the station in search of my family I could not find them anywhere. Survivors told me that my entire family, including my parents and five siblings, had been hacked,” he says.

Ashraf now works as a tailor at Karachi’s Orangi Town. He was very young when the turmoil started in Kalsagram. “My father, who was in the police, never returned after March 26. I can’t tell the exact place but my mother was also killed during the massacre,” he narrates his ordeal.

Ashraf says he was later shifted to some other location along with 50 to 60 children who were taken care of by some Bengalis. “These children were later rescued by the Pakistan Army. My elder sister lived in Dhaka. She found me in the army’s protection and took me along to Dhaka,” he adds.

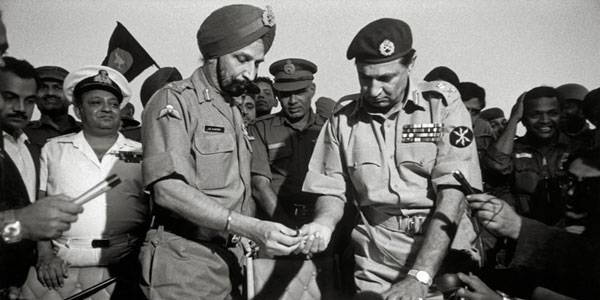

PHOTOS PROVIDED BY SYED PERVEZ AFSAR

Commenting on the Bangladesh government’s claim that three million Bengalis were killed during the military operation that Pakistan Army started in March 1971, Sarmila Bose in her ‘Death Reckoning’ writes that history of Bangladesh is the history written by the victors of war.

While falsifying the highly exaggerated Bangladeshi and Indian claims about the deaths of Bengalis, Bose in her monumental work on the 1971 war notes that the only group whose killing could qualify the definition of genocide were non-Bengali residents of East Pakistan.

According to the whitepaper published in March 1971, around one hundred thousand non-Bengalis were killed in various parts of East Pakistan till that time. However, the later estimates based on the post-April counting suggest that the total number of non-Bengalis killed by Mukti Bahini was around two hundred and fifty thousand.

While sporadic killing of non-Bengalis took place all across the former East Pakistan, their mass massacres took place particularly in Jessore, Isherdee, Chandragona Paper Mills of Chittagong, Admajee Jute Mills of Narayanganj and Santahar of Rashahi. In remembrance of the martyrs of these massacres, The Express Tribune presents accounts of a few survivors.

How Mukti Bahini ‘cleansed’ Santahar of non-Bengalis

Haji Ehsanullah was 19 years old when his neighbourhood in Loco West was attacked by a Bengali mob on March 26. He says he along with his father, mother and wife jumped into a relative’s house and hid in a bathroom.

“When the attackers were gone, we first went to a graveyard and spend the night there. The coming days were spent in Ghorahaat, Santahar Railway Station and Station Colony,” he adds.

Ehsanullah remembers how on the morning of April 17, the Mukti Bahini launched its final assault against the unarmed residents of the colony.

“When the attack started, my parents asked me to run away. I covered my face with a kerchief and went out holding a metal rod in my hand,” he says, adding that the massacre was in full swing and he saw Bengali men throwing little children into the adjoining pond. “I was also stopped by a group of Bengalis who wanted to kill me, but a man, Aakaash, intervened and said that he knew me and that I was a Bengali.”

He says Aakaash’s colleagues were not much convinced and one of the group members gave me a shovel to dig out a grave. “I started digging a ditch while my people were being killed. I frantically kept digging.”

Ehsanullah says the same Bengali, Aakaash, again came to him in the afternoon, offered him some food and gave him address of his sister, who lived in the town of Ontahar.

Ehsanullah says he somehow managed to get to that place, where he was given refuge until arrival of Pakistan Army on April 22. “When I returned to Santahar, in search of my family, I could not find my parents, but my wife was alive. The killers had slit her neck but she had survived as the wound was not deep enough,” he adds.

Dr Jameel Akhtar, who now lives in Shah Faisal Colony of Karachi, says his entire family – comprising his parents and 10 siblings – was killed in the April 16 massacre at Railway Colony.

“I was among the youngest kids of my parents. When the attack started at around 4am, we hugged each other. But my parent asked me to escape and clad me in a lungi and vest. My mother also gave me her gold jewellery which I hid in a fold in my lungi.”

Dr Jameel says when the attackers reached their house, his elder brother opened the door. “I was standing behind him. I saw them killing my brother right in front of my eyes.”

He says he ran out from the backside of his house. “I rushed to the railway station but saw a Bengali railway officer, Jalal Guard, prowling there with a spear in his hand. I ran from there but I soon found myself in front of another group of killers.”

Dr Jameel says he tried to convince the Mukti Bahini men that he was also a Bengali but they did not believe him. “They were about to hit me when I had an idea. I brought out the jewellery from my lungi and threw it in front of them. The killers instantly started vying for the gold, giving me an opportunity to escape.”

Forgotten pages: The martyrs of Naogaon Cantonment

Dr Jameel says he then started moving towards Naogaon. “But on that way, I encountered with another group of killers who had put on display half a dozen human heads. They asked me who I was. I told them that I am a Bengali. The asked me as to what was the slogan for that day. On my way, I had seen a slogan written on the walls. I told them it’s ‘Amar Desh, Tumar Desh, Bangladesh, Bangladesh’. I was fortunate, they let me go,” he says.

Bilquis, who now lives in Karachi’s Orangi Town, was a married woman with three children in 1971. She says when the Bengalis started attacking different neighbourhoods, her husband decided to move along with the family to the factory of Gramophone beri-wala.

“Here the hooligans of Mukti Bahini came and picked up men who were often slaughtered outside the factory. My husband was also among those who was killed outside that premises,” she reminisces.

Bilquis says despite all the killings in and outside the factory, she and her family remained in that building until April 17 when Bengalis asked them to move to the Railway Colony.

“I along with other women was being driven to the station when a Bengali man, who knew my husband and called me her sister, came to me and told me in whispers that I should not go to the station as all people were being killed there,” she says.

“The other Bengalis were not ready at first to allow me to go with him but he somehow managed to convince them. He later took me to his family, who gave refuge to me.”

Bilquis says the other women who had left the factory with her were brought to a pond where they were slaughtered. “I was, however, fortunate that I remained safe and also found my children alive,” she adds.

Irfan Ulllah Siddiqui was a little kid when his family was massacred in the Station Colony on April 17.

“My family comprised my parents, six daughters and three brothers. All of them were killed. I was 6-year-old at that time and managed to survive as I hid beneath the bodies of my family members,” he recalls, adding that it was many days after the massacre that he was discovered by her aunt who lived in Saidpur and had come in search of survivors of her family.

Muhammad Qurban, who now lives in Karachi’s Malir area, was 19 years old in March 1971. He was among the people who buried the victims of the March 27 killing at Chaibagan Mosque.

“My family had moved to the railway station after this attack. However, on April 2, I left the station and somehow reached Naogaon,” he recalls, adding that he stayed at Naogaon until the arrival of the Pakistan Army.

“When I returned to the station in search of my family I could not find them anywhere. Survivors told me that my entire family, including my parents and five siblings, had been hacked,” he says.

Ashraf now works as a tailor at Karachi’s Orangi Town. He was very young when the turmoil started in Kalsagram. “My father, who was in the police, never returned after March 26. I can’t tell the exact place but my mother was also killed during the massacre,” he narrates his ordeal.

Ashraf says he was later shifted to some other location along with 50 to 60 children who were taken care of by some Bengalis. “These children were later rescued by the Pakistan Army. My elder sister lived in Dhaka. She found me in the army’s protection and took me along to Dhaka,” he adds.

PHOTOS PROVIDED BY SYED PERVEZ AFSAR