ghazi52

PDF THINK TANK: ANALYST

- Joined

- Mar 21, 2007

- Messages

- 101,791

- Reaction score

- 106

- Country

- Location

.,.,

Zehra Khan

19 Aug, 2023

Sindhis and my family have nothing in common, except that Sindh gave us a home when we didn’t have one. Sindhis are part of that fortunate cadre of people who have lovingly inhabited the same piece of land for centuries, building a vast and colourful culture of language and literature, music and folklore, clothing and food. Their food habits and recipes have been passed down generations, maturing and developing with time yet always finding themselves at home.

Unfortunately, people cannot traverse borders as freely and without ruptures as fish. When my family migrated from Bihar to East Pakistan and then from Bangladesh to Pakistan, eating three meals a day was put to a test. And as often happens, it fell upon the women of my family to find a common ground and make a home out of it. While beh (lotus root), makhaanay (lotus seeds), pua pitha (a kind of sweet rice-flour pancake) and singhaara/pani phal (water chestnut) were easily available, kachha kathal (raw durian), kacha kela (raw bananas) and bataali gur (jaggery) got left behind until much later when my grandfather discovered Musa Colony and Machhar Colony, the secret havens of Bengali food and culture in Karachi, living on silently but resiliently despite state-sanctioned discrimination.

Since both Sindh and Bangladesh heavily rely on their vast freshwater and saltwater resources, my family looked at the Sindhu Darya and thought of the Ganga that flowed outside their home in Dhaka. And Hilsa Bhaat or the Sindhi Palla became the common ground we began to call home.

Food is liked or disliked by a people in accordance with the topography and climate they inhabit.

Since the fertile lands of Punjab are rife with fields of wheat and other grains, flatbread or rotis of different kinds are considered fundamental for a filling meal. In Sindh, both roti and rice are prepared in a variety of ways and sometimes also served one with the other. For Bengalis, the food story is entirely different. Rice is the basis of life itself, soaking up the juices of its partner gravies and being arguably the best companion to seafood. Like Sindhis, we even eat roti with rice!

The fish is known to grow very large and muscular as it swims upstream, against the flow of the Indus, with a distinct taste quite different from other freshwater fish. It is believed that each fish is only blessed with the unique taste of Palla after it swims all the way up to the shrine of Jhulay Lal in Sukkur. I then spoke to the mother of another Sindhi friend who confirmed these details and also narrated to me a mouthwatering recipe of fried Pallo fish with rice — the most common way Pallo is prepared and served in Sindh.

After cleaning the insides and removing the head of the fish, cuts are made on either side of its belly and it is liberally marinated in salt, pepper, chilli powder and turmeric powder. As the fish rests, rice is boiled and spread onto the serving dish.

Next comes the daag masala, a Sindhi specialty. In about three tablespoons of hot vegetable oil, ginger, green chillies, finely chopped onions and salt is added and cooked until the onions sweat and turn golden brown, releasing a sweetly tart flavour.

Then tomatoes, turmeric, red chilli powder, coriander and cumin powders and garam masala is added and cooked for about 20 minutes, adding a dash of water to rehydrate the mixture.

Once the masala is ready, it is seasoned to taste and set aside. Meanwhile, the fish is fried in hot vegetable oil in a pan until fully cooked and crispy around the edges, quite unlike Bengalis, who don’t usually fry fish. The fried fish is then placed on top of the bed of rice and steamed for 10 minutes so that its flavours and spices seep into the rice.

This is why the perfect preparation of rice is important to tie the dish together and to add a carbohydrate to the largely protein-rich dish. The dish is served with lemon and coriander.

The most formative memory of my childhood is Dadda, my grandmother, tucking her pallu into her petticoat as she went through the routine motions of measuring, washing, soaking and boiling white rice or bhaat. To me, bhaat is the joy of life. The stiff rice grains boiled and bubbled in a huge pot of saltwater, frothing with starch and swelling with moisture until firm enough to hold its shape yet soft enough to mush between the tongue and palate. Dadda would then strain the aromatic rice and set it aside to cool, collecting the starchy water or maar, full of the goodness of the rice.

Dadda used to say, “Bhaat does not have byproducts.” Give the maar to a baby and she will grow up tall and strong; run it through your hair and you won’t ever lose a strand again. The bhaat itself would be served with lentils or daal and a vegetable or meat gravy. Then you could puff the rice and enjoy the murmuray or flatten it and chomp on the chewra. When it would grow a few days old, there would be bowls of panta bhaat or baasi bhaat in the fridge waiting for my rumbling evening tummy.

But the best days were seafood days. A world of fish and prawns, cooked in gravy and pan-fried in simmering oil, I’d be able to smell it from my parent’s room and my five-year-old feet would carry me straight into Dadda’s arms in the kitchen, her anchoring me against her left hip while she cooked with her right hand. When Dadda grew old, her diabetes worsening her health, the doctor advised her to skimp on the rice. And Dadda argued and haggled about this limitation like a child until the day she left us. We think she didn’t consider life without rice worth living.

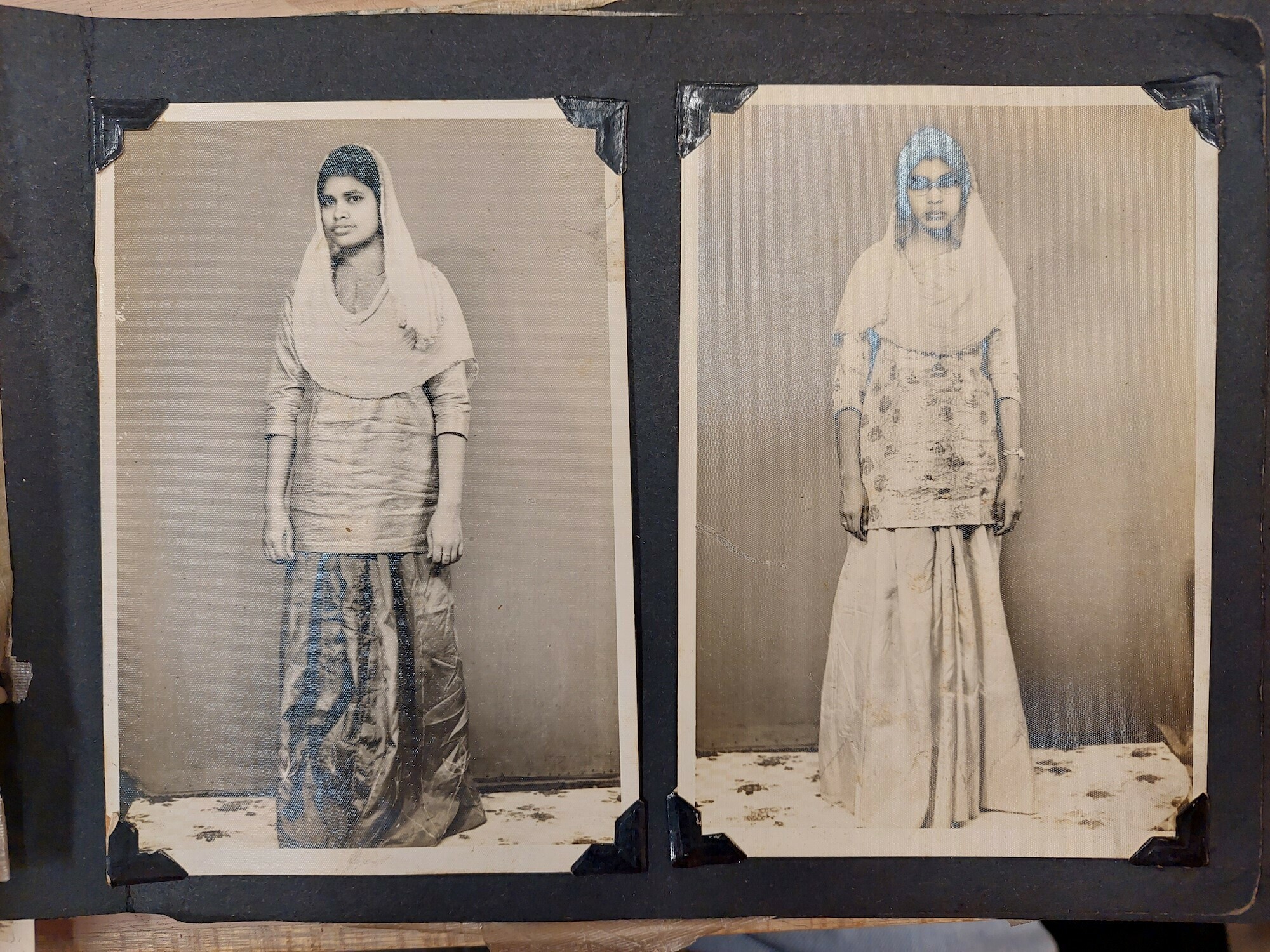

My grandmothers

A few days ago, while speaking to a relative settled in Lahore, I discovered a shocking food preference — there are some vegetable and even meat-based dishes that are considered best eaten with chapaati/roti in the majority of the northern part of Pakistan. As a person of Bihari descent and with roots in present-day Bangladesh, the idea that wheat instead of rice can ever be the preferred carbohydrate supplement in a meal is unimaginable to me. Herein lies the science of food preference.

Pallo is Hilsa or Ilish to Bengalis. The centre of a vast variety of Bengali literature and famously, the favorite fish of Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore, Hilsa is considered a symbol of monsoon rain, wealth and prosperity by Bengalis. In many a poem, the fish has been used to portray the highs and lows of life itself and to form the Bengali identity. Dadda would tell me that the marker of a true Bengali is to eat the fish while simultaneously separating its many bones in the mouth. So that’s how I learnt to eat it.

At an age when parents would carefully pick food apart for their children, Dadda fed me juicy bites of rice and fish, too big for my mouth, teaching me how to separate the bones of the Hilsa myself.

Nano, my maternal grandmother, is as fantastic a cook as my Dadda was, so I asked her to narrate her recipe for the fish to me. Between meanderings about her difficult journey with her parents from Bangladesh to Pakistan in 1971, Nano recalled the recipe through memory without so much as a single pause of doubt.

Nano informed me that Bengalis don’t have lentils with rice and that daal is the part of our food we borrow from our Bihari heritage. Because of this, Hilsa is cooked in gravy instead of being fried to go with bhaat. For the gravy, fresh ginger, garlic and onions are finely chopped and added to some oil in a pan. Bengalis do not brown their onions when cooking with them and they use very little ginger and garlic to cook fish.

As in the case of Pallo Chawal, tomatoes, turmeric powder and red chilli powder are added to the mixture and it is cooked until it is well done and aromatic. To this, Nano added that the tomatoes they had in Bangladesh were smaller, redder and more ripe than we can find here so they would disintegrate almost instantly in the gravy, letting out their juices.

The Hilsa is cut into smaller pieces width-wise and lightly sautéed with salt, pepper and turmeric powder marinated on all sides. Once the fish is sautéed enough to hold its form, it is carefully put one after the other in the gravy, soya (a herb also generously used in Sindh to prepare daag) and water added to it and the dish is cooked on a low flame, lest the fish breaks apart. This deliciously protein-rich dish is served topped with coriander.

Today, the population of Pallo or Hilsa in the Bay of Bengal is dwindling rapidly due to overfishing.

A fundamental part of the diets of both Sindhi and Bengali people, the fish reminds some that they’ve been home for centuries and some of the home they lost. As the River Indus and Ganges continue to flow and nurture civilisations around them, Pallo/Hilsa tell the tales of resistance in these regions and urge us to consider swimming upstream, against the current, if that’s what it takes to preserve ourselves.

Bengali Hilsa Bhaat and Sindhi Pallo Chawal — where cuisines and cultures collide

It’s not just their love for the fish that makes Bengalis and Sindhis alike. It’s their recipes, too!Zehra Khan

19 Aug, 2023

Sindhis and my family have nothing in common, except that Sindh gave us a home when we didn’t have one. Sindhis are part of that fortunate cadre of people who have lovingly inhabited the same piece of land for centuries, building a vast and colourful culture of language and literature, music and folklore, clothing and food. Their food habits and recipes have been passed down generations, maturing and developing with time yet always finding themselves at home.

Unfortunately, people cannot traverse borders as freely and without ruptures as fish. When my family migrated from Bihar to East Pakistan and then from Bangladesh to Pakistan, eating three meals a day was put to a test. And as often happens, it fell upon the women of my family to find a common ground and make a home out of it. While beh (lotus root), makhaanay (lotus seeds), pua pitha (a kind of sweet rice-flour pancake) and singhaara/pani phal (water chestnut) were easily available, kachha kathal (raw durian), kacha kela (raw bananas) and bataali gur (jaggery) got left behind until much later when my grandfather discovered Musa Colony and Machhar Colony, the secret havens of Bengali food and culture in Karachi, living on silently but resiliently despite state-sanctioned discrimination.

Since both Sindh and Bangladesh heavily rely on their vast freshwater and saltwater resources, my family looked at the Sindhu Darya and thought of the Ganga that flowed outside their home in Dhaka. And Hilsa Bhaat or the Sindhi Palla became the common ground we began to call home.

Food is liked or disliked by a people in accordance with the topography and climate they inhabit.

Since the fertile lands of Punjab are rife with fields of wheat and other grains, flatbread or rotis of different kinds are considered fundamental for a filling meal. In Sindh, both roti and rice are prepared in a variety of ways and sometimes also served one with the other. For Bengalis, the food story is entirely different. Rice is the basis of life itself, soaking up the juices of its partner gravies and being arguably the best companion to seafood. Like Sindhis, we even eat roti with rice!

Pallo — The King of Fish

When I asked my friend for a reliable Sindhi recipe of the fish, our conversation strayed and fell into folklore. Palla or Pallo, as it is called in Sindh, is a fleshy, silver-skinned fish which is largely considered the Machher Raja or the King of Fish. Through the fish, I found out about Jhulay Lal or, as he is locally called by both Sindhi Hindus and Muslims, Zinda Pir (The Living Saint), the revered saint who is believed to control the currents of the Indus River and of whom I had only heard of in song. In many depictions of the saint, he is seen sitting on a large Pallo fish atop a lotus flower.The fish is known to grow very large and muscular as it swims upstream, against the flow of the Indus, with a distinct taste quite different from other freshwater fish. It is believed that each fish is only blessed with the unique taste of Palla after it swims all the way up to the shrine of Jhulay Lal in Sukkur. I then spoke to the mother of another Sindhi friend who confirmed these details and also narrated to me a mouthwatering recipe of fried Pallo fish with rice — the most common way Pallo is prepared and served in Sindh.

After cleaning the insides and removing the head of the fish, cuts are made on either side of its belly and it is liberally marinated in salt, pepper, chilli powder and turmeric powder. As the fish rests, rice is boiled and spread onto the serving dish.

Next comes the daag masala, a Sindhi specialty. In about three tablespoons of hot vegetable oil, ginger, green chillies, finely chopped onions and salt is added and cooked until the onions sweat and turn golden brown, releasing a sweetly tart flavour.

Then tomatoes, turmeric, red chilli powder, coriander and cumin powders and garam masala is added and cooked for about 20 minutes, adding a dash of water to rehydrate the mixture.

Once the masala is ready, it is seasoned to taste and set aside. Meanwhile, the fish is fried in hot vegetable oil in a pan until fully cooked and crispy around the edges, quite unlike Bengalis, who don’t usually fry fish. The fried fish is then placed on top of the bed of rice and steamed for 10 minutes so that its flavours and spices seep into the rice.

This is why the perfect preparation of rice is important to tie the dish together and to add a carbohydrate to the largely protein-rich dish. The dish is served with lemon and coriander.

Hilsa Bhaat and the smell of childhood

The most formative memory of my childhood is Dadda, my grandmother, tucking her pallu into her petticoat as she went through the routine motions of measuring, washing, soaking and boiling white rice or bhaat. To me, bhaat is the joy of life. The stiff rice grains boiled and bubbled in a huge pot of saltwater, frothing with starch and swelling with moisture until firm enough to hold its shape yet soft enough to mush between the tongue and palate. Dadda would then strain the aromatic rice and set it aside to cool, collecting the starchy water or maar, full of the goodness of the rice.

Dadda used to say, “Bhaat does not have byproducts.” Give the maar to a baby and she will grow up tall and strong; run it through your hair and you won’t ever lose a strand again. The bhaat itself would be served with lentils or daal and a vegetable or meat gravy. Then you could puff the rice and enjoy the murmuray or flatten it and chomp on the chewra. When it would grow a few days old, there would be bowls of panta bhaat or baasi bhaat in the fridge waiting for my rumbling evening tummy.

But the best days were seafood days. A world of fish and prawns, cooked in gravy and pan-fried in simmering oil, I’d be able to smell it from my parent’s room and my five-year-old feet would carry me straight into Dadda’s arms in the kitchen, her anchoring me against her left hip while she cooked with her right hand. When Dadda grew old, her diabetes worsening her health, the doctor advised her to skimp on the rice. And Dadda argued and haggled about this limitation like a child until the day she left us. We think she didn’t consider life without rice worth living.

My grandmothers

A few days ago, while speaking to a relative settled in Lahore, I discovered a shocking food preference — there are some vegetable and even meat-based dishes that are considered best eaten with chapaati/roti in the majority of the northern part of Pakistan. As a person of Bihari descent and with roots in present-day Bangladesh, the idea that wheat instead of rice can ever be the preferred carbohydrate supplement in a meal is unimaginable to me. Herein lies the science of food preference.

Pallo is Hilsa or Ilish to Bengalis. The centre of a vast variety of Bengali literature and famously, the favorite fish of Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore, Hilsa is considered a symbol of monsoon rain, wealth and prosperity by Bengalis. In many a poem, the fish has been used to portray the highs and lows of life itself and to form the Bengali identity. Dadda would tell me that the marker of a true Bengali is to eat the fish while simultaneously separating its many bones in the mouth. So that’s how I learnt to eat it.

At an age when parents would carefully pick food apart for their children, Dadda fed me juicy bites of rice and fish, too big for my mouth, teaching me how to separate the bones of the Hilsa myself.

Nano, my maternal grandmother, is as fantastic a cook as my Dadda was, so I asked her to narrate her recipe for the fish to me. Between meanderings about her difficult journey with her parents from Bangladesh to Pakistan in 1971, Nano recalled the recipe through memory without so much as a single pause of doubt.

Nano informed me that Bengalis don’t have lentils with rice and that daal is the part of our food we borrow from our Bihari heritage. Because of this, Hilsa is cooked in gravy instead of being fried to go with bhaat. For the gravy, fresh ginger, garlic and onions are finely chopped and added to some oil in a pan. Bengalis do not brown their onions when cooking with them and they use very little ginger and garlic to cook fish.

As in the case of Pallo Chawal, tomatoes, turmeric powder and red chilli powder are added to the mixture and it is cooked until it is well done and aromatic. To this, Nano added that the tomatoes they had in Bangladesh were smaller, redder and more ripe than we can find here so they would disintegrate almost instantly in the gravy, letting out their juices.

The Hilsa is cut into smaller pieces width-wise and lightly sautéed with salt, pepper and turmeric powder marinated on all sides. Once the fish is sautéed enough to hold its form, it is carefully put one after the other in the gravy, soya (a herb also generously used in Sindh to prepare daag) and water added to it and the dish is cooked on a low flame, lest the fish breaks apart. This deliciously protein-rich dish is served topped with coriander.

Today, the population of Pallo or Hilsa in the Bay of Bengal is dwindling rapidly due to overfishing.

A fundamental part of the diets of both Sindhi and Bengali people, the fish reminds some that they’ve been home for centuries and some of the home they lost. As the River Indus and Ganges continue to flow and nurture civilisations around them, Pallo/Hilsa tell the tales of resistance in these regions and urge us to consider swimming upstream, against the current, if that’s what it takes to preserve ourselves.

Bengali Hilsa Bhaat and Sindhi Pallo Chawal — where cuisines and cultures collide

It’s not just their love for the fish that makes Bengalis and Sindhis alike. It’s their recipes, too!

images.dawn.com