Black Day- Part 1

The next day, we were told that Colonel Habibur Rehman, who was travelling with Netaji in the ill-fated aircraft, was arriving by a relief plane, and that he was in a serious condition and had sustained severe burns on his face and body. A delegation was dispatched to the airport to receive him, and he was brought to Mr Sahay’s house. He was indeed in a very bad condition with burns on one side of his face, and a large burn patch on his body.

Two days later, Mr Tatsuo Hayashida, a Japanese officer, arrived from Taihoku with Netaji’s ashes. The cube-shaped urn was covered in white cloth. Mr SA Ayer who was the Minister of Publicity in the Azad Hind Government and a right-hand man of Netaji was in Tokyo then, and it was decided that the ashes be kept in the safe custody of one of Tokyo’s shrines. The place decided upon was the Renkoji Temple in the city centre of Tokyo.

We gathered there one night and in a simple ceremony performed by the head priest of the Renkoji Temple, the ashes were kept in a place of honour with a photograph of Netaji in full INA uniform in front of the urn. The ashes are still there. Neither the Indian government nor Netaji’s close relations have deemed it fit to bring them over to India, even after all these years. The government’s reluctance to do so was an aspect of politics, but the family clearly believed that he could not have died.

All those who kept up the pretense that Netaji was alive, even after the Government of India’s enquiry committees had disproved the theory, had some purpose to their plan. However, no one realised that they were insulting the memory of a great revolutionary who, in the heat and turmoil of a world war, managed to travel secretly from Germany to Malaya in a submarine and then galvanized the entire southeast Asian Indian community into forming the Azad Hind government and the Indian National Army. Would such a great man, if he were alive, stay in hiding?I believe that if Netaji had been alive and not killed in the air crash, he would have returned to India after the British left its shores. And if he had come in at that time, he might have stolen the hearts of the populace and taken the place that other leaders took. Netaji was shrewd and far-sighted, and he made the national language Hindustani, not Hindi, and the language of common people. The script was democratically roman.

Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, more than being a born leader, was an able commander who could, and more importantly, did take decisions. There was no vacillation in his demeanor or actions. He was strong-willed, like the immortal Sardar Vallabhai Patel, and if both these men had been alive at this time, they would have done great things for the country, but that was not to be. Netaji died at a very inopportune juncture of the nation’s birth.

Coming back to our story in Japan, a building was hired for us and we shifted into it. We were five to a room, as the 35 from the erstwhile Army Academy now joined us. Money was no problem, as apart from the large sum we had been given earlier, we were getting a monthly allowance. The only snag was that there was almost nothing for sale and we had no boarding facilities. We had to fend for ourselves. Somehow, we managed quite comfortably. We used to send foraging parties to the farms in the suburbs of Tokyo, and get fresh vegetables, fruit and other foodstuff. In fact we were doing better than the Japanese authorities had managed to in the last two years.

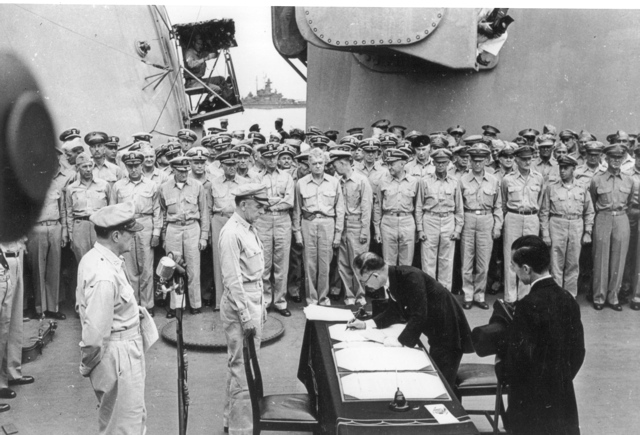

Consequent to the Emperor’s declaration of unconditional surrender, the Japanese envoys signed the Instrument of Surrender aboard the US battleship USS Missouri, and the Second World War came to an official end. We waited apprehensively for the Americans to land in Tokyo. It was certain that the Japanese would receive them with discipline and decorum, since the Emperor willed it, but we were not too sure of the kind of reception we would receive when they found out about us.

Japanese envoy signs the surrender document aboard the battleship U.S.S. Missouri in Tokyo Bay

Under American Occupation

The day and the manner in which the Americans landed was memorable. Transport planes escorted by hordes of fighter- and bomber-aircraft appeared over the Tokyo landscape. People may at first have misunderstood this and thought that the War was on again and an attack imminent. But this was not the case. The Americans had probably done this with a dual purpose. Clearly, they wanted to display their awesome might. This was also a preemptive measure.

As the planes landed one by one on the runway, the fighters hovered overhead on guard. As the troops disembarked, they deployed and boarded trucks and jeeps that were to take them in a victory procession through the streets of Tokyo.

There were no disturbances and not a single hand was raised against them. Instead, the public had lined up in the streets and children waved to them. It was typical of American diplomacy that they made friends, especially with the children by giving them chewing gum and chocolates.

The start of the occupation of Japan went like clockwork, with the full cooperation of the vanquished.

Many of the American officers and others we met later told us that they had landed with apprehension, expecting that the Japanese would take revenge on them for the bombing.

They too wanted to take revenge on the citizens for Japan’s having waged such an expensive war—expensive in terms of the number of American dead and wounded.

But when they actually saw the civilian population, they could not believe that the polite, disciplined and friendly people were of the same stock as the brutal hard-fighting front-line soldiers they had faced earlier. This was exactly how we felt when we first came to Japan from the war-torn areas of Burma, Malaya and the Philippines.

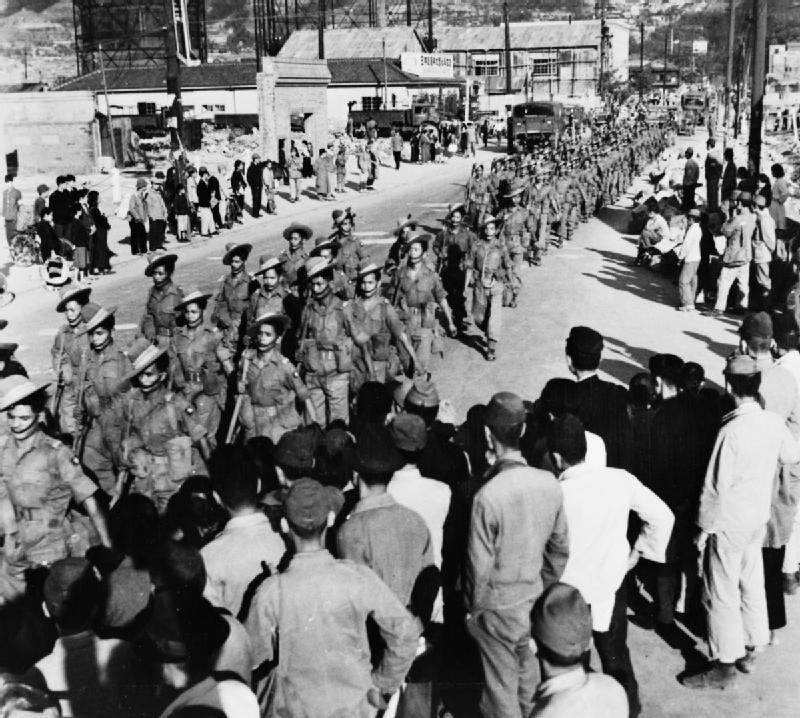

The 2nd Battalion 5th Royal Gurkha Rifles march through Kure

Within days, everything was back to peacetime conditions. Of course, some of the GIs made a lot of money by selling American cigarettes and chocolates to the half-starved civilians, and the US Military Police had a hard time trying to block this. However, both sides profited from the deal. The Japanese civilians, who hadn’t tasted chocolates or smoked a cigarette since the War began, were quite happy to pay for such a luxury, and the GIs made some local spending money over and above their comparatively substantial pay packets.

After a few days of occupation, our representative met the American authorities. They did not know what to do with us. One of the officers said that they had nothing against us and went on to joke that the Americans had also fought the same British for their Independence. They also premised that in due course they would be able to repatriate us to India if we so wished. We were very relieved when we heard this, and to crown our happiness, they even supplied us with their ‘K’ rations and group packs.

We experienced abundance, American style. The ‘K’ ration packet was a meal in itself and contained all the necessary items including a packet of three cigarettes for an after-dinner smoke. The group pack was a regular Christmas hamper as far as we were concerned. It contained cocoa, tea, coffee, biscuits, cakes, meat-loaves, corned beef, soup, chocolates and many other things. The large cardboard container was meant for eight to ten people, but we managed to send it round to many more persons than that. With such an abundance of good food that we had not had for years, life for us became an eating binge, perhaps as a reaction to the two years of starvation diet that we had been forced to maintain.

Somehow, just when everything seemed to be going well, the proverbial fly in the ointment appeared. A rude and offensive officer, Colonel Figges, a senior member of the British counterpart of the Allied Occupation Forces Authority, took charge. This man went after us. He ordered that our representative should report to his headquarters immediately. We sensed trouble and tried to delay the confrontation, but in the end we were forced to comply.

A few of us representing the 45-strong contingent reported to his office one morning. To put it mildly, we were given a hostile reception.

He began by saying that we were all traitors and that if had he had his way, we would all be shot. We politely but firmly told him that we were not traitors as we never owed allegiance to the British, and that we were very proud to have served and taken part in the INA in the fight for the independence of India.

These were brave words for us and should have been applauded, but the Englishman was inflamed, and what infuriated him even further was that he could not mete out severe punishment at this stage. He did not have the power or the facilities to arrest and detain us, and the Americans were too busy to cooperate with him in this venture. He finally said he would ensure that we were all rounded up and moved to India for just retribution. We walked out of his office in protest.

Colonel Figges did manage to force the American authorities to put us in the Fourth Repatriation Centre of the US Occupation Forces. This was the start of our incarceration, but a really mild one as I will relate.

The Fourth Repatriation Centre happened to be located in the same Japanese Army Academy premises where our 35 Army cadets had been training until recently. When we moved here, we were given a part of the barracks for our stay. Although we were not allowed to leave camp, we had freedom within the premises. The good thing was that we were given the same food and other rations that the GIs were given. This meant that we were supplied coupons for our daily ration of beer. Not one of us drank at the time, so we exchanged these coupons with some hard-drinking GIs for more chocolate and chewing gum.

Chow-time was a revelation to us. The queues for breakfast, lunch and dinner were the same for officers and men. Each of us was given a mess plate which had compartments in it, and when we reached the serving counter, we were given very large portions of corned beef, cabbage, beans in tomato sauce, slices of fresh bread, a sweet and a mug full of hot milk to which we could add coffee or cocoa and sugar. Our stomachs had probably shrunk. One such serving could easily have fed about four of us, so the first two days we did waste a lot of food.

We were also witness to criminal waste in the kitchen. Large canisters of milk from the cold storage would be opened, and when the meal was over for the day, the leftover milk would be up-ended from the canisters into the gutter alongside the camp kitchen. What a wicked waste this seemed when so many children outside the camp starved. It was the same with the rest of the food leftovers. It showed two things—the callousness with which food was wasted, and the fact that the Americans produced an abundance of food for their troops. An American officer told us that if their government wanted their men to fight a war, they had better see to it that corned-beef got to the frontline before the troops did as their army literally marched on its stomach.

Although we were told that black people were treated badly in America at that time, there seemed to be no discrimination between the few black soldiers and the white GIs in the camp as far as food and facilities were concerned. There were practically no black officers, though.

We were detenues and our freedom was restricted in that we could not leave camp, but the stay here was such a change from our earlier existence—almost like a holiday—that none of us minded the delay in our repatriation. Every evening, they showed us a film at the NAAFI centre, with free snacks served in the interval. We must all have put on a few pounds in our short stay there. We were supplied with the GI gabardine shirts and trousers, and all the basic necessities such toothpaste, shaving kits, jackets and kit bags. We were told that as soon as the rush on their aircraft receded, we would be sent to Singapore via Manila on their US Air Force Skymaster aircraft.

We now went on a buying spree. We knew that all the Japanese money we had would be worthless once we left the country, so we bought what we could and whatever was easily available—wrist watches, especially the waterproof kind issued to the GIs, rolls of Japanese silk smuggled into the camp, silk kimonos for both men and women and anything else which would serve as presents for our family and friends when and if we were finally reunited with them. Even after we had bought there things, we were left with huge sums of money. This amount, together with the autographed photo of Netaji, which we thought would be safer here and could be collected at a later date, was left with our Captain Kato. Unfortunately, we never got our things back.

@levina

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------