LeveragedBuyout

SENIOR MEMBER

- Joined

- May 16, 2014

- Messages

- 1,958

- Reaction score

- 60

- Country

- Location

Part II in a continuing series, this thread dealing with the events precipitating a Thucydides Trap between the United States and China. The Thucydides Trap was coined by a Harvard professor to refer to a scenario where "a rising power causes fear in an established power, which escalates towards war" (per the Wikipedia definition). Previous examples of this include Athens challenging Sparta, and the German Empire challenging the British Empire. Will the Chinese challenge to the United States become another such event?

The Road To War (Part I: Trade)

The Road to War (Part II: The Thucydides Trap) - This Thread

As Tensions Continue, China Has No Interest in Backing Down to the U.S. - China Real Time Report - WSJ

By Ying Ma

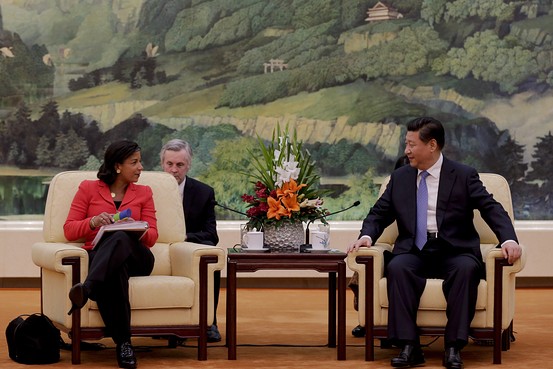

U.S. National Security Advisor Susan Rice talked with Chinese President Xi Jinping during a meeting at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing.

Associated Press

U.S. National Security Advisor Susan Rice visited China earlier this month to pave the way for President Barack Obama’s upcoming meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping after an Asia-Pacific trade summit in Beijing this November. Rice’s visit produced no breakthroughs, and each side walked away having voiced their gripes against the other.

In many ways, Rice’s visit was indicative of a Sino-American relationship that is currently fraught with tension. Prior to Obama’s November visit, his administration should do some serious soul searching about its China policy.

In the face of a rising and more assertive China, many in Washington have argued that the United States must demonstrate firmer resolve to force China to back down from challenging the U.S.-led security order in Asia. These recommendations are dangerous, argues Hugh White, professor of Strategic Studies at the Australian National University, because China is serious about challenging U.S. primacy in Asia and has no interest in backing down.

Obama’s detractors blame the president for having emboldened China and sowed doubts about U.S. alliances in Asia by appearing feckless before threats from Syria, Russia and the Islamic State. Prof. White believes, on the contrary, that more robust threats from Washington to punish Beijing for provocations would only heighten the risk of Sino-American confrontation.

Prof. White’s warning helps explain the obstacles in America’s current interactions with China. The Obama administration in recent months has attempted to step up its deterrence against China with tougher rhetoric, more categorical commitments to allies in Asia and a beefed-up U.S. military presence in the region.

In April, President Barack Obama reiterated that U.S. defense obligations to Japan include islands claimed by China, and noted that U.S. treaty commitments to the Philippines, another country with whom China has territorial disputes, are “iron-clad.” His administration has also negotiated the return of American troops to the Philippines and signed a new Force Posture Agreement with Australia to deploy 2,500 Marines to Down Under.

A Chinese coast guard vessel, right, fired water cannon at a Vietnamese vessel off the coast of Vietnam after China deployed an oil rig in disputed South China Sea waters.

Associated Press

More In China-US

Many in the U.S. policy community believe that Obama is simply not pushing back against Beijing hard enough. Prof. White suggests, however, that pushing back was never the winning formula. “When Obama declared he was determined to preserve the status quo [of power in Asia],” he wrote earlier this summer, “China was supposed to back off graciously. But it didn’t work. Instead Beijing pushed back harder, by escalating its maritime disputes with U.S. friends and allies.”

China has come to view the U.S. as the biggest culprit for heightened tensions in the region. Wu Xinbo, director of the Center for American Studies and Executive Dean of the Institute of International Studies at Fudan University, said soon after China deployed its oil rig off the coast of Vietnam that when smaller countries in Asia confront China on territorial disputes, “they are not confronting China alone… they have the U.S. behind them.”

Amid the finger pointing and heightened regional tensions, two scenarios offer the possibility of averting the catastrophic consequences of breakdown in the U.S.-China relationship. Prof. White provides one such solution in his book, The China Choice: Why America Should Share Power: The U.S. should relinquish primacy in Asia and negotiate a power-sharing arrangement with China.

The problem is that a China-dominated Asia is one that many countries in Asia would resist and one that even the most knee-jerk China advocate in Washington would not endorse. U.S. gestures of cooperation and reassurance in the security realm, though having produced some results, have also failed to elicit more cooperative behavior from Beijing overall. Just this summer, the U.S. Navy engaged in some significant trust building with the Chinese military and welcomed China as a first-time participate in the U.S.-led Rim of the Pacific naval exercise (RIMPAC) in Hawaii, the largest international maritime exercise in the world. During the exercises, China became the first Rimpac participant to send a reconnaissance ship to international waters near the drills to conduct surveillance on the other participants. Then on Aug. 19, just a few weeks after the exercises concluded, China sent a fighter jet to intercept and harass a U.S. military reconnaissance aircraft flying in international air space off China’s southern coast.

These instances do not suggest that Beijing wishes to play nice.

Huang Jing, director of the Centre on Asia and Globalisation at Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy has argued that there is ultimately only one thing China can do to avert Sino-American confrontation: foster a democratic transition through political reform. Without such reforms, Prof. Huang contends, the U.S. will ultimately view China as a threat and will seek to contain its rise—even if both countries seek peace.

While some believe that such a political transition in China is well on its way, most other China observers expect China’s current rulers and political system to remain in place for the quite some time.

Without game changers such as the relinquishment of U.S. primacy in Asia and a transition to democratic liberalization in China, the U.S. and China could be left wrestling with heightened tensions and potential armed conflict for the foreseeable future.

In a world where Beijing does not intend to back down, Washington’s displays of resolve might continue to lead Beijing to push back harder. Strengthening U.S. deterrence against Chinese provocations could still remain justified for other good reasons, but a U.S. foreign policy based on the assumption of Beijing’s speedy retreat could be horribly mistaken.

The Road To War (Part I: Trade)

The Road to War (Part II: The Thucydides Trap) - This Thread

As Tensions Continue, China Has No Interest in Backing Down to the U.S. - China Real Time Report - WSJ

- September 23, 2014, 5:30 AM HKT

By Ying Ma

U.S. National Security Advisor Susan Rice talked with Chinese President Xi Jinping during a meeting at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing.

Associated Press

U.S. National Security Advisor Susan Rice visited China earlier this month to pave the way for President Barack Obama’s upcoming meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping after an Asia-Pacific trade summit in Beijing this November. Rice’s visit produced no breakthroughs, and each side walked away having voiced their gripes against the other.

In many ways, Rice’s visit was indicative of a Sino-American relationship that is currently fraught with tension. Prior to Obama’s November visit, his administration should do some serious soul searching about its China policy.

In the face of a rising and more assertive China, many in Washington have argued that the United States must demonstrate firmer resolve to force China to back down from challenging the U.S.-led security order in Asia. These recommendations are dangerous, argues Hugh White, professor of Strategic Studies at the Australian National University, because China is serious about challenging U.S. primacy in Asia and has no interest in backing down.

Obama’s detractors blame the president for having emboldened China and sowed doubts about U.S. alliances in Asia by appearing feckless before threats from Syria, Russia and the Islamic State. Prof. White believes, on the contrary, that more robust threats from Washington to punish Beijing for provocations would only heighten the risk of Sino-American confrontation.

Prof. White’s warning helps explain the obstacles in America’s current interactions with China. The Obama administration in recent months has attempted to step up its deterrence against China with tougher rhetoric, more categorical commitments to allies in Asia and a beefed-up U.S. military presence in the region.

In April, President Barack Obama reiterated that U.S. defense obligations to Japan include islands claimed by China, and noted that U.S. treaty commitments to the Philippines, another country with whom China has territorial disputes, are “iron-clad.” His administration has also negotiated the return of American troops to the Philippines and signed a new Force Posture Agreement with Australia to deploy 2,500 Marines to Down Under.

A Chinese coast guard vessel, right, fired water cannon at a Vietnamese vessel off the coast of Vietnam after China deployed an oil rig in disputed South China Sea waters.

Associated Press

More In China-US

- Chinese Hacked U.S. Military Contractors 20 Times in a Year

- Bad Timing: China Activist's Trial Opens With U.S. Envoy in Town

- Going Maverick: Lessons from China's Buzzing of a U.S. Navy Aircraft

- Aerial Aggression: Chinese Intercepts of U.S. Planes Raise Alarm

- Divide and Conquer? Chinese Navy Starts Playing Nice With U.S.

Many in the U.S. policy community believe that Obama is simply not pushing back against Beijing hard enough. Prof. White suggests, however, that pushing back was never the winning formula. “When Obama declared he was determined to preserve the status quo [of power in Asia],” he wrote earlier this summer, “China was supposed to back off graciously. But it didn’t work. Instead Beijing pushed back harder, by escalating its maritime disputes with U.S. friends and allies.”

China has come to view the U.S. as the biggest culprit for heightened tensions in the region. Wu Xinbo, director of the Center for American Studies and Executive Dean of the Institute of International Studies at Fudan University, said soon after China deployed its oil rig off the coast of Vietnam that when smaller countries in Asia confront China on territorial disputes, “they are not confronting China alone… they have the U.S. behind them.”

Amid the finger pointing and heightened regional tensions, two scenarios offer the possibility of averting the catastrophic consequences of breakdown in the U.S.-China relationship. Prof. White provides one such solution in his book, The China Choice: Why America Should Share Power: The U.S. should relinquish primacy in Asia and negotiate a power-sharing arrangement with China.

The problem is that a China-dominated Asia is one that many countries in Asia would resist and one that even the most knee-jerk China advocate in Washington would not endorse. U.S. gestures of cooperation and reassurance in the security realm, though having produced some results, have also failed to elicit more cooperative behavior from Beijing overall. Just this summer, the U.S. Navy engaged in some significant trust building with the Chinese military and welcomed China as a first-time participate in the U.S.-led Rim of the Pacific naval exercise (RIMPAC) in Hawaii, the largest international maritime exercise in the world. During the exercises, China became the first Rimpac participant to send a reconnaissance ship to international waters near the drills to conduct surveillance on the other participants. Then on Aug. 19, just a few weeks after the exercises concluded, China sent a fighter jet to intercept and harass a U.S. military reconnaissance aircraft flying in international air space off China’s southern coast.

These instances do not suggest that Beijing wishes to play nice.

Huang Jing, director of the Centre on Asia and Globalisation at Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy has argued that there is ultimately only one thing China can do to avert Sino-American confrontation: foster a democratic transition through political reform. Without such reforms, Prof. Huang contends, the U.S. will ultimately view China as a threat and will seek to contain its rise—even if both countries seek peace.

While some believe that such a political transition in China is well on its way, most other China observers expect China’s current rulers and political system to remain in place for the quite some time.

Without game changers such as the relinquishment of U.S. primacy in Asia and a transition to democratic liberalization in China, the U.S. and China could be left wrestling with heightened tensions and potential armed conflict for the foreseeable future.

In a world where Beijing does not intend to back down, Washington’s displays of resolve might continue to lead Beijing to push back harder. Strengthening U.S. deterrence against Chinese provocations could still remain justified for other good reasons, but a U.S. foreign policy based on the assumption of Beijing’s speedy retreat could be horribly mistaken.

Last edited: