The Radical Truth: Teaching MPACUK the forgotten chapter of Pakistan's history

It's common knowledge that Pakistan does not teach its school children the truth about its brutalities during 1971, when East Pakistan broke away to become Bangladesh. The Guinness Book of Records lists the Bangladesh Genocide as one of the top 5 genocides in the 20th century, yet it's hardly featured in Pakistan's textbooks, academic discussion or the media. On the 40th Victory Day of Bangladesh, BBC Radio 4 documented how the Pakistani school children perceive Bangladesh Liberation War, they're in a state of denial of Pakistan's genocide of Bengali people in former East Pakistan. They have been taught by the propagandist a conspiracy of Hindu Indians causing tensions between the two Muslim wings of Pakistan. The children's deny Pakistanis could ever do such things to their brothers and sisters in Bangladesh! In one sense these children are also suffering abuse by their own government by being denied the truth. Pakistanis are suffering from this curse even today except of course, the military elite who live on American handouts to the tune of billions of dollars.

As one Pakistani historian in UK writes:

The roots of the civil war in 1971 are of course in the partition of 1947 and the establishment of Pakistan. Since Muhammad Ali Jinnah wanted a partition on the basis of religion alone, East and West Pakistan came into being, despite the thousand mile distance and different racial, cultural and political inheritances the only common thread was the fact that both wings were a Muslim majority. In a way, the success or failure of this experiment was the practical test of the two-nation theory. From the beginning, however, there were clear tensions between the two wings. The first one was a clash over national language (to be clear, English was to remain the official language). The Bengalis, with thousands of years of culture behind them, obviously wanted their language recognised as coequal to Urdu, not least because they did not speak Urdu. Nevertheless, Jinnah categorically refused the Bengali demand in his speech at Dacca University in February 1948, igniting the flame of linguistic nationalism. It is, of course, an irony that Jinnah himself was never fluent in Urdu and spoke mostly in English to the Bengali crowd.

In 1971, over 9 months, President Yahya Khan and his military commanders with the aid of local collaborators committed mass atrocities on unarmed civilians, killed an estimated three million people, raped over 300,000 women, destroyed innumerable homes to crush the rebellion, which was termed an Indian-inspired conspiracy. The minority Hindu community was particularly targeted. This unprecedented atrocities led to a mass exodus to India, where an estimated 10 million people took refuge. Further readings Genocide Bangladesh and Bangladesh Liberation War

It seems that vast majority of Pakistanis in the UK are also clueless as to the true extent of what happened in 1971. Like in Pakistan, there isn't much discussion in the UK by Pakistanis or groups run by predominantly Pakistanis. This includes Muslim Public Affair Committee UK (MPACUK) a group claiming to be the largest Muslim lobbing group representing British Muslims. Although this group has done some good work they have many flaws, including shying away from stating fundamental Islamic principals that contradicts UK laws e.g. on homosexuality, feminism and women's role, Sharia law, emigration of Muslins etc. In its mission statements, it claims to have the interest of Muslims close to its heart and aims to empower them, yet on the subject of Pakistan's genocide in Bangladesh MPACUK is silent. Bangladeshis make up a large proportion of the UK Muslim population, however they are desperately lagging behind other ethnic minority groups. MPACUK likes to highlight persecutions of Muslims around the world but when it's Muslims against Muslims, they are silent. The war of 1971 plays a major role in shaping the Bangladeshi community in Britain, with important dates being celebrated throughout the year as a way to remember their sacrifice. MPACUK's silence is evident on its website with not a single article chronicling the events of 1971.

One of their article from 2010 Pakistan: Nothing To Celebrate? talks about Pakistan's false sense of independence but fails to mention the important history of East Pakistan's breakaway. Instead it incorrectly refers to the partition and birth of Pakistan as liberation of approximately 400 million Muslims, in Pakistan and Bangladesh, omitting the violent separation of East Pakistan to form independent Bangladesh in 1971. The above population figure is also wrong as it is of modern day Pakistan and Bangladesh and not of West and East Pakistan after partition (Independence of Pakistan). MPACUK must have Pakistan's text book in its library, where the chapter about the birth of Bangladesh and Pakistan's genocide in 1971 is missing.

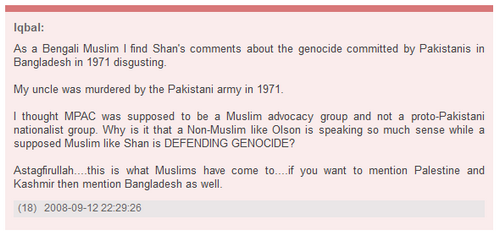

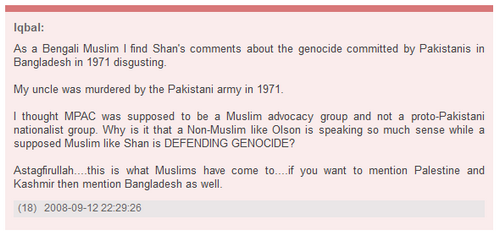

Another of their article from 2008 "The Septembers of Our Lives" - about the 1982 massacre of 3,500 unarmed civilians in Palestinian refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila in Beirut, Lebanon. In the readers comments section, there is a debate between 'Shan' - a Pakistani nationalist and denier of Bangladesh genocide versus 'Olson' - who is presenting figures of the genocide from various sources and accounts of Bangladeshi work colleagues. Iqbal a Bengali Muslim, after reading Shan's disgusting comments replied (see below) by highlighting MPACUK's failure in allowing such genocide denying pro-Pakistani nationalist comments. He also suggested that if crimes in Palestine and Kashmir in mentioned then to mention the genocide in Bangladesh too. Did MPACUK heed this? No. Is there any wonder why people like Shan deny Pakistan's genocide in Bangladesh?

A reader's comment on "The Septembers of Our Lives"

The lack of information about Bangladesh Liberation War was highlighted to MPACUK by e-mail (see below). It was met with ignorance, even the request for an answer from the CEO went ignored. One wonders why? MPACUK's 4 core principals are Reviving the obligation of Jihad, Anti-Zionism, Institutional Revival, and Accountability. These are just buzz words to MPACUK as it does not fully explain or understand terms like Jihad etc. but selectively define them to fit their own weak agenda. Where is the accountability when they choose to ignore important subjects that highlights the crimes of Pakistan and everyone's failure to teach this history? MPACUK's ignorance of these e-mails says a lot about this group i.e. it's run by a bunch of amateur, ignorant, uneducated, childish youths of Pakistani ethnic origin. It's not a mainstream organisation representing UK Muslims but more of a cult that is run by few for the few, who think they are right and everyone else is wrong.

Unless we understand our own history and repent for our failings, how can Muslims in the UK progress? Pakistan has not unequivocally asked for forgiveness for killing hundreds of thousands of its fellow citizens. The wound is being kept green. Anyone denying this crime is also a criminal. MPACUK likes to hold others accountable but accountability has no meaning when others hold MPACUK accountable. We challenge them to prove this wrong. We also challenge them to be transparent by publishing its CEO's and board members for the last decade to prove it's not a mere cult.

Update: 10 March 2012

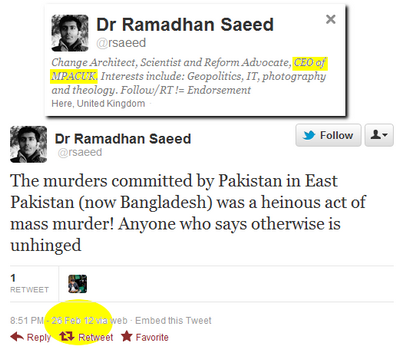

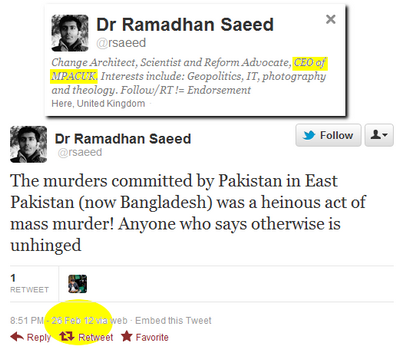

After reading this blog on the 26th of Feb 2012, Ramadhan Saeed, CEO of MPACUK must have been panicked. Having realised the above points were valid and credible, Ramadhan Saeed in his moment of chaos, tweeted this paltry gesture on Bangladesh genocide! Note the date when he wrote the message on tweeter, it was after he read this blog. He then posted the abysmal comment below on behalf of MPACUK with a link to this tweet, denying his group has any pro-Pakistan bias. I think you would disagree very much with Dr Saeed. The points raised above are still being ignored by MPACUK and Dr Saeed. What a childish behaviour!

E-mails to MPACUK

4th E-MAIL (to CEO)

From:

To: "info@mpacuk.org" <info@mpacuk.org>

Sent: Tuesday, 18 October 2011, 23:49

Subject: For the attention of MPAC CEO

Dear brother/sister

Salam, I would like to bring a matter to your attention. Recently I sent your organisation several e-mails on the important topic of 1971 Bangladesh war - to date I have not received a single reply.

Either your organisation wants nothing to do with this subject or you have staffing/e-mail issues. Your organisation likes to hold others accountable but when others hold you accountable, it is a different matter. Can you see the hypocrisy in this?

I guess this message will go ignored too. Genocide is like a nightmare - it keeps coming back unless we deal with it.

3rd E-MAIL

From:

To: "info@mpacuk.org" <info@mpacuk.org>

Sent: Monday, 3 October 2011, 23:41

Subject: Re: Remembering East Pakistan

Salam,

I was expecting a reply to this, I have written to you for the 3rd time. I'm disappointed with you lack of response.

2nd E-MAIL

From:

To: "info@mpacuk.org" <info@mpacuk.org>

Sent: Friday, 16 September 2011, 22:31

Subject: Remembering East Pakistan

As-Salamu Alaykum,

I sent this e-mail just over a week ago, wondering if you received it and what you think of my suggestion.

Hope to hear from you.

Kind Regards,

1st E-MAIL

From:

To: "info@mpacuk.org" <info@mpacuk.org>

Sent: Thursday, 8 September 2011, 23:49

Subject: Remembering East Pakistan

As-Salamu Alaykum,

I often visit your website and enjoy reading the news and analysis.

Recently I came across an article about the history of genocide in Bangladesh during 1971. I did not know about this. It could be due to my ignorance or lack of information.

Would you kindly post a link to this article so people may learn about this sad chapter of so many British Muslims of Bangladeshi origin. I have not read much, if any on your website regarding this.

Look forward to hearing from you.

Kind Regards,

Remembering East Pakistan I

The writer is a historian at Keble College, University of Oxford

At this time forty years ago, our government was busy conducting, what some Western diplomats then termed, selective genocide in its own country in East Pakistan. Let alone that we should be collectively repenting and asking for forgiveness for what West Pakistan unleashed on the eastern wing, the events of 1971 are hardly ever mentioned in Pakistani textbooks, in academic discussions or the media. I had hoped that at least on March 26, the day the Bengalis declared their independence from Pakistan, there would be some indication of sorrow in the public sphere over the atrocities of 1971 but that hope was in vain. The recognition, acceptance and repentance of those acts is not just an academic exercise, but also important for us if we want to develop into a mature and responsible country.

The roots of the civil war in 1971 are of course in the partition of 1947 and the establishment of Pakistan. Since Muhammad Ali Jinnah wanted a partition on the basis of religion alone, East and West Pakistan came into being, despite the thousand mile distance and different racial, cultural and political inheritances the only common thread was the fact that both wings were a Muslim majority. In a way, the success or failure of this experiment was the practical test of the two-nation theory. From the beginning, however, there were clear tensions between the two wings. The first one was a clash over national language (to be clear, English was to remain the official language). The Bengalis, with thousands of years of culture behind them, obviously wanted their language recognised as coequal to Urdu, not least because they did not speak Urdu. Nevertheless, Jinnah categorically refused the Bengali demand in his speech at Dacca University in February 1948, igniting the flame of linguistic nationalism. It is, of course, an irony that Jinnah himself was never fluent in Urdu and spoke mostly in English to the Bengali crowd.

It is impossible to chart here the sad history of the unequal treatment of East Pakistan by the western wing, but it is important to note that the same democratic process through which Pakistan was created (the Muslim League had swept the Muslim seats in the 1946 elections in British India), was denied to the East Pakistanis repeatedly. Not only were national elections postponed due to fear of Bengali rule, the 1954 United Front victory in East Bengal was never accepted by the western wing, and the disregard of the 1970 elections led to the vivisection of the country.

The events of 1971 should have shaken us so much that a new polity based on equality, democracy and justice could have been established. However, while we were shocked by the debacle, we simply blamed it on India and the treacherous Bengalis, and soon resumed our ways. Simply put, we learnt nothing from the 1971 experience, and therefore, we need to revisit and learn from it.

Out of the many lessons of the 1971 debacle, let me highlight just two issues here: First, we need to accept the fact that the East Bengalis did have a legitimate right to the acceptance of their culture within Pakistan. The Muslims of India spoke a wide variety of languages and were part of very different cultures, but a country which was formed as a homeland for the Muslims had to recognise and celebrate such diversity within an overarching Muslim framework, rather than subsuming it within a north Indian, Urdu centric, cultural idiom. Our current reaction to Baloch, Sindhi and Pakhtun nationalism has much to learn from the Bengali experience.

Secondly, we need to accept and ask forgiveness for the atrocities of 1971 categorically and without exception. From Operation Searchlight to the final surrender to the Indian and Bangla forces in December 1971, we, the Pakistanis, need to ask unequivocally for forgiveness for killing hundreds of thousands of our fellow citizens. The wounds of 1971 will never heal if we do not recognise and repent for the horrors the West Pakistani forces unleashed on their East Pakistani brethren and how it finally hit the nails in the coffin of the two-nation theory.

Published in The Express Tribune, August 2nd, 2011.

Remembering East Pakistan II

In March this year, the prime minister and foreign minister of Bangladesh visited Oxford. I noticed that I was the only Pakistani among a gathering of mainly Bangladeshis and Britons. Conscious of the past, I gathered courage and went up to Sheikh Hasina and introduced myself. After an initial cold look, she quickly warmed up to me when I mentioned that I greatly respected her father and what he stood for in a united Pakistan. Then began reminisces clearly still hurtful of East Pakistan and 1970-1. The atrocities of 1971 were still fresh in their minds and it was clear that episode was a critical phase in the formation of their national identity. What was patent to me by the end of the conversation was that we in Pakistan have almost forgotten and refuse to learn from that experience.

I recently read an article by Professor Yasmin Saikia (the Hardt-Nickachos Chair in Peace Studies at the Center for the Study of Religion at Arizona State University) in which she analysed the interviews of Pakistani soldiers who had been in East Pakistan in 1971. Repeatedly what came out in the interviews was that they had been force-fed the propaganda that everyone in East Pakistan was a Hindu traitor and therefore deserved harsh treatment. This demonisation of fellow countrymen (most Mukhti Bahini were East Pakistanis) is perhaps the reason why we still refuse to engage with the real issues the debacle raised. After all, if they were all evil Hindu Indians, then what can we learn from them? The truth, as usual in Pakistan, is not what we have been officially told.

Let me point out two interrelated issues. First, the 1971 incidents should have shaken us as normal human beings. Most of the soldiers Professor Saikia interviewed said that in some way they felt thatinsaniyat (humanity) had been abandoned. They were traumatised by the scale and depth of the atrocities carried out by Pakistani soldiers, since they were asked to behave towards the Bengalis as if they were lower than even animals. This dehumanising of the other still continues unabated in our public discourse. Our penchant of embarking on a military operation against our own people (twice in Balochistan since 1971, for instance) and even our random killing of political foes (for example in Karachi) shows how we still continue to treat a lot of people as sub-human not worthy to live if they dont agree with our perspective on something. Insaniyat is something we clearly lost in 1971, and still need to (re)gain.

Secondly, most big disasters usually begin with a sobering/reflective phase in a country. However, we seem to have skipped that period. Not only did we not publicly take stock of the situation (the Hamoodur Rehman Commission Report was only declassified in 2000 and that too via an Indian news organisation), we almost immediately acted as if nothing wrong had happened. In one of the most shocking of moves, the Pakistani government appointed General Tikka Khan as the chief of army in 1972 barely a year after he was called the Butcher of Bengal by Time and other commentators for his role in the mass killings of East Pakistanis. Here again we acted without any insaniyat. Rather than court-martialling and removing General Tikka, we honoured him further.

One of the premises of the two-nation theory was that the Muslims and Hindus of India had different heroes. Mahmud Ghaznavi was a champion for the Muslims but a brutal murderer for the Hindus; Shivaji was a valiant fighter for the Marhatta Hindu cause but a treacherous insurgent for Aurangzeb, and so on. However, 1971 created that rift between even Muslims. Every pupil in Pakistan reads about the heroic virtue of Rashid Minhas who, while a trainee pilot, brought down the plane flown by his trainer when he realised that he was defecting to Bangladesh. We gave Rashid Minhas the Nishan-e-Haider, our highest award, and Matiur Rahman, the trainer, our traitor, was given the Bir Sreshtho Bangladeshs highest award.

What distinguishes us is perhaps not just our religion, but ourinsaniyat. If we can treat others with respect, we can live with almost anyone.

Published in The Express Tribune, August 9th, 2011.

It's common knowledge that Pakistan does not teach its school children the truth about its brutalities during 1971, when East Pakistan broke away to become Bangladesh. The Guinness Book of Records lists the Bangladesh Genocide as one of the top 5 genocides in the 20th century, yet it's hardly featured in Pakistan's textbooks, academic discussion or the media. On the 40th Victory Day of Bangladesh, BBC Radio 4 documented how the Pakistani school children perceive Bangladesh Liberation War, they're in a state of denial of Pakistan's genocide of Bengali people in former East Pakistan. They have been taught by the propagandist a conspiracy of Hindu Indians causing tensions between the two Muslim wings of Pakistan. The children's deny Pakistanis could ever do such things to their brothers and sisters in Bangladesh! In one sense these children are also suffering abuse by their own government by being denied the truth. Pakistanis are suffering from this curse even today except of course, the military elite who live on American handouts to the tune of billions of dollars.

As one Pakistani historian in UK writes:

The roots of the civil war in 1971 are of course in the partition of 1947 and the establishment of Pakistan. Since Muhammad Ali Jinnah wanted a partition on the basis of religion alone, East and West Pakistan came into being, despite the thousand mile distance and different racial, cultural and political inheritances the only common thread was the fact that both wings were a Muslim majority. In a way, the success or failure of this experiment was the practical test of the two-nation theory. From the beginning, however, there were clear tensions between the two wings. The first one was a clash over national language (to be clear, English was to remain the official language). The Bengalis, with thousands of years of culture behind them, obviously wanted their language recognised as coequal to Urdu, not least because they did not speak Urdu. Nevertheless, Jinnah categorically refused the Bengali demand in his speech at Dacca University in February 1948, igniting the flame of linguistic nationalism. It is, of course, an irony that Jinnah himself was never fluent in Urdu and spoke mostly in English to the Bengali crowd.

In 1971, over 9 months, President Yahya Khan and his military commanders with the aid of local collaborators committed mass atrocities on unarmed civilians, killed an estimated three million people, raped over 300,000 women, destroyed innumerable homes to crush the rebellion, which was termed an Indian-inspired conspiracy. The minority Hindu community was particularly targeted. This unprecedented atrocities led to a mass exodus to India, where an estimated 10 million people took refuge. Further readings Genocide Bangladesh and Bangladesh Liberation War

It seems that vast majority of Pakistanis in the UK are also clueless as to the true extent of what happened in 1971. Like in Pakistan, there isn't much discussion in the UK by Pakistanis or groups run by predominantly Pakistanis. This includes Muslim Public Affair Committee UK (MPACUK) a group claiming to be the largest Muslim lobbing group representing British Muslims. Although this group has done some good work they have many flaws, including shying away from stating fundamental Islamic principals that contradicts UK laws e.g. on homosexuality, feminism and women's role, Sharia law, emigration of Muslins etc. In its mission statements, it claims to have the interest of Muslims close to its heart and aims to empower them, yet on the subject of Pakistan's genocide in Bangladesh MPACUK is silent. Bangladeshis make up a large proportion of the UK Muslim population, however they are desperately lagging behind other ethnic minority groups. MPACUK likes to highlight persecutions of Muslims around the world but when it's Muslims against Muslims, they are silent. The war of 1971 plays a major role in shaping the Bangladeshi community in Britain, with important dates being celebrated throughout the year as a way to remember their sacrifice. MPACUK's silence is evident on its website with not a single article chronicling the events of 1971.

One of their article from 2010 Pakistan: Nothing To Celebrate? talks about Pakistan's false sense of independence but fails to mention the important history of East Pakistan's breakaway. Instead it incorrectly refers to the partition and birth of Pakistan as liberation of approximately 400 million Muslims, in Pakistan and Bangladesh, omitting the violent separation of East Pakistan to form independent Bangladesh in 1971. The above population figure is also wrong as it is of modern day Pakistan and Bangladesh and not of West and East Pakistan after partition (Independence of Pakistan). MPACUK must have Pakistan's text book in its library, where the chapter about the birth of Bangladesh and Pakistan's genocide in 1971 is missing.

Another of their article from 2008 "The Septembers of Our Lives" - about the 1982 massacre of 3,500 unarmed civilians in Palestinian refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila in Beirut, Lebanon. In the readers comments section, there is a debate between 'Shan' - a Pakistani nationalist and denier of Bangladesh genocide versus 'Olson' - who is presenting figures of the genocide from various sources and accounts of Bangladeshi work colleagues. Iqbal a Bengali Muslim, after reading Shan's disgusting comments replied (see below) by highlighting MPACUK's failure in allowing such genocide denying pro-Pakistani nationalist comments. He also suggested that if crimes in Palestine and Kashmir in mentioned then to mention the genocide in Bangladesh too. Did MPACUK heed this? No. Is there any wonder why people like Shan deny Pakistan's genocide in Bangladesh?

A reader's comment on "The Septembers of Our Lives"

The lack of information about Bangladesh Liberation War was highlighted to MPACUK by e-mail (see below). It was met with ignorance, even the request for an answer from the CEO went ignored. One wonders why? MPACUK's 4 core principals are Reviving the obligation of Jihad, Anti-Zionism, Institutional Revival, and Accountability. These are just buzz words to MPACUK as it does not fully explain or understand terms like Jihad etc. but selectively define them to fit their own weak agenda. Where is the accountability when they choose to ignore important subjects that highlights the crimes of Pakistan and everyone's failure to teach this history? MPACUK's ignorance of these e-mails says a lot about this group i.e. it's run by a bunch of amateur, ignorant, uneducated, childish youths of Pakistani ethnic origin. It's not a mainstream organisation representing UK Muslims but more of a cult that is run by few for the few, who think they are right and everyone else is wrong.

Unless we understand our own history and repent for our failings, how can Muslims in the UK progress? Pakistan has not unequivocally asked for forgiveness for killing hundreds of thousands of its fellow citizens. The wound is being kept green. Anyone denying this crime is also a criminal. MPACUK likes to hold others accountable but accountability has no meaning when others hold MPACUK accountable. We challenge them to prove this wrong. We also challenge them to be transparent by publishing its CEO's and board members for the last decade to prove it's not a mere cult.

Update: 10 March 2012

After reading this blog on the 26th of Feb 2012, Ramadhan Saeed, CEO of MPACUK must have been panicked. Having realised the above points were valid and credible, Ramadhan Saeed in his moment of chaos, tweeted this paltry gesture on Bangladesh genocide! Note the date when he wrote the message on tweeter, it was after he read this blog. He then posted the abysmal comment below on behalf of MPACUK with a link to this tweet, denying his group has any pro-Pakistan bias. I think you would disagree very much with Dr Saeed. The points raised above are still being ignored by MPACUK and Dr Saeed. What a childish behaviour!

E-mails to MPACUK

4th E-MAIL (to CEO)

From:

To: "info@mpacuk.org" <info@mpacuk.org>

Sent: Tuesday, 18 October 2011, 23:49

Subject: For the attention of MPAC CEO

Dear brother/sister

Salam, I would like to bring a matter to your attention. Recently I sent your organisation several e-mails on the important topic of 1971 Bangladesh war - to date I have not received a single reply.

Either your organisation wants nothing to do with this subject or you have staffing/e-mail issues. Your organisation likes to hold others accountable but when others hold you accountable, it is a different matter. Can you see the hypocrisy in this?

I guess this message will go ignored too. Genocide is like a nightmare - it keeps coming back unless we deal with it.

3rd E-MAIL

From:

To: "info@mpacuk.org" <info@mpacuk.org>

Sent: Monday, 3 October 2011, 23:41

Subject: Re: Remembering East Pakistan

Salam,

I was expecting a reply to this, I have written to you for the 3rd time. I'm disappointed with you lack of response.

2nd E-MAIL

From:

To: "info@mpacuk.org" <info@mpacuk.org>

Sent: Friday, 16 September 2011, 22:31

Subject: Remembering East Pakistan

As-Salamu Alaykum,

I sent this e-mail just over a week ago, wondering if you received it and what you think of my suggestion.

Hope to hear from you.

Kind Regards,

1st E-MAIL

From:

To: "info@mpacuk.org" <info@mpacuk.org>

Sent: Thursday, 8 September 2011, 23:49

Subject: Remembering East Pakistan

As-Salamu Alaykum,

I often visit your website and enjoy reading the news and analysis.

Recently I came across an article about the history of genocide in Bangladesh during 1971. I did not know about this. It could be due to my ignorance or lack of information.

Would you kindly post a link to this article so people may learn about this sad chapter of so many British Muslims of Bangladeshi origin. I have not read much, if any on your website regarding this.

Look forward to hearing from you.

Kind Regards,

Remembering East Pakistan I

The writer is a historian at Keble College, University of Oxford

At this time forty years ago, our government was busy conducting, what some Western diplomats then termed, selective genocide in its own country in East Pakistan. Let alone that we should be collectively repenting and asking for forgiveness for what West Pakistan unleashed on the eastern wing, the events of 1971 are hardly ever mentioned in Pakistani textbooks, in academic discussions or the media. I had hoped that at least on March 26, the day the Bengalis declared their independence from Pakistan, there would be some indication of sorrow in the public sphere over the atrocities of 1971 but that hope was in vain. The recognition, acceptance and repentance of those acts is not just an academic exercise, but also important for us if we want to develop into a mature and responsible country.

The roots of the civil war in 1971 are of course in the partition of 1947 and the establishment of Pakistan. Since Muhammad Ali Jinnah wanted a partition on the basis of religion alone, East and West Pakistan came into being, despite the thousand mile distance and different racial, cultural and political inheritances the only common thread was the fact that both wings were a Muslim majority. In a way, the success or failure of this experiment was the practical test of the two-nation theory. From the beginning, however, there were clear tensions between the two wings. The first one was a clash over national language (to be clear, English was to remain the official language). The Bengalis, with thousands of years of culture behind them, obviously wanted their language recognised as coequal to Urdu, not least because they did not speak Urdu. Nevertheless, Jinnah categorically refused the Bengali demand in his speech at Dacca University in February 1948, igniting the flame of linguistic nationalism. It is, of course, an irony that Jinnah himself was never fluent in Urdu and spoke mostly in English to the Bengali crowd.

It is impossible to chart here the sad history of the unequal treatment of East Pakistan by the western wing, but it is important to note that the same democratic process through which Pakistan was created (the Muslim League had swept the Muslim seats in the 1946 elections in British India), was denied to the East Pakistanis repeatedly. Not only were national elections postponed due to fear of Bengali rule, the 1954 United Front victory in East Bengal was never accepted by the western wing, and the disregard of the 1970 elections led to the vivisection of the country.

The events of 1971 should have shaken us so much that a new polity based on equality, democracy and justice could have been established. However, while we were shocked by the debacle, we simply blamed it on India and the treacherous Bengalis, and soon resumed our ways. Simply put, we learnt nothing from the 1971 experience, and therefore, we need to revisit and learn from it.

Out of the many lessons of the 1971 debacle, let me highlight just two issues here: First, we need to accept the fact that the East Bengalis did have a legitimate right to the acceptance of their culture within Pakistan. The Muslims of India spoke a wide variety of languages and were part of very different cultures, but a country which was formed as a homeland for the Muslims had to recognise and celebrate such diversity within an overarching Muslim framework, rather than subsuming it within a north Indian, Urdu centric, cultural idiom. Our current reaction to Baloch, Sindhi and Pakhtun nationalism has much to learn from the Bengali experience.

Secondly, we need to accept and ask forgiveness for the atrocities of 1971 categorically and without exception. From Operation Searchlight to the final surrender to the Indian and Bangla forces in December 1971, we, the Pakistanis, need to ask unequivocally for forgiveness for killing hundreds of thousands of our fellow citizens. The wounds of 1971 will never heal if we do not recognise and repent for the horrors the West Pakistani forces unleashed on their East Pakistani brethren and how it finally hit the nails in the coffin of the two-nation theory.

Published in The Express Tribune, August 2nd, 2011.

Remembering East Pakistan II

In March this year, the prime minister and foreign minister of Bangladesh visited Oxford. I noticed that I was the only Pakistani among a gathering of mainly Bangladeshis and Britons. Conscious of the past, I gathered courage and went up to Sheikh Hasina and introduced myself. After an initial cold look, she quickly warmed up to me when I mentioned that I greatly respected her father and what he stood for in a united Pakistan. Then began reminisces clearly still hurtful of East Pakistan and 1970-1. The atrocities of 1971 were still fresh in their minds and it was clear that episode was a critical phase in the formation of their national identity. What was patent to me by the end of the conversation was that we in Pakistan have almost forgotten and refuse to learn from that experience.

I recently read an article by Professor Yasmin Saikia (the Hardt-Nickachos Chair in Peace Studies at the Center for the Study of Religion at Arizona State University) in which she analysed the interviews of Pakistani soldiers who had been in East Pakistan in 1971. Repeatedly what came out in the interviews was that they had been force-fed the propaganda that everyone in East Pakistan was a Hindu traitor and therefore deserved harsh treatment. This demonisation of fellow countrymen (most Mukhti Bahini were East Pakistanis) is perhaps the reason why we still refuse to engage with the real issues the debacle raised. After all, if they were all evil Hindu Indians, then what can we learn from them? The truth, as usual in Pakistan, is not what we have been officially told.

Let me point out two interrelated issues. First, the 1971 incidents should have shaken us as normal human beings. Most of the soldiers Professor Saikia interviewed said that in some way they felt thatinsaniyat (humanity) had been abandoned. They were traumatised by the scale and depth of the atrocities carried out by Pakistani soldiers, since they were asked to behave towards the Bengalis as if they were lower than even animals. This dehumanising of the other still continues unabated in our public discourse. Our penchant of embarking on a military operation against our own people (twice in Balochistan since 1971, for instance) and even our random killing of political foes (for example in Karachi) shows how we still continue to treat a lot of people as sub-human not worthy to live if they dont agree with our perspective on something. Insaniyat is something we clearly lost in 1971, and still need to (re)gain.

Secondly, most big disasters usually begin with a sobering/reflective phase in a country. However, we seem to have skipped that period. Not only did we not publicly take stock of the situation (the Hamoodur Rehman Commission Report was only declassified in 2000 and that too via an Indian news organisation), we almost immediately acted as if nothing wrong had happened. In one of the most shocking of moves, the Pakistani government appointed General Tikka Khan as the chief of army in 1972 barely a year after he was called the Butcher of Bengal by Time and other commentators for his role in the mass killings of East Pakistanis. Here again we acted without any insaniyat. Rather than court-martialling and removing General Tikka, we honoured him further.

One of the premises of the two-nation theory was that the Muslims and Hindus of India had different heroes. Mahmud Ghaznavi was a champion for the Muslims but a brutal murderer for the Hindus; Shivaji was a valiant fighter for the Marhatta Hindu cause but a treacherous insurgent for Aurangzeb, and so on. However, 1971 created that rift between even Muslims. Every pupil in Pakistan reads about the heroic virtue of Rashid Minhas who, while a trainee pilot, brought down the plane flown by his trainer when he realised that he was defecting to Bangladesh. We gave Rashid Minhas the Nishan-e-Haider, our highest award, and Matiur Rahman, the trainer, our traitor, was given the Bir Sreshtho Bangladeshs highest award.

What distinguishes us is perhaps not just our religion, but ourinsaniyat. If we can treat others with respect, we can live with almost anyone.

Published in The Express Tribune, August 9th, 2011.