The Raid that ‘Ended a War’: The RAF in the Third Afghan War, 1919

Jun 25, 2019 ·

By Group Captain John Alexander

A Bristol F.2B Fighter of 31 Squadron patrolling the North-West Frontier. © Crown Copyright / Ministry of Defence. Courtesy of Air Historical Branch (RAF).

When Captain Jock Halley’s Handley Page V/1500,

Old Carthusian, dropped 20 bombs on Kabul on 24 May 1919, one 112 and three 20-pound bombs hit the Amir’s Palace, sending the ladies of the royal harem into the streets in terror, causing great scandal. Another three 112 and seven 20-pounders hit the royal arsenal at Arg, causing a large explosion.

[1] As a result Halley later claimed to have ‘ended the war on his own.’

[2] As the subsequent

Official History of the campaign records, the contribution of a handful of obsolete aircraft was one of the main military lessons of the war:

One hundred years on, the rapid adaptation of what the RAF’s first formal doctrine was to call ‘Co-operation of Aircraft with the Army’ and ‘Independent Operations’ on the North West Frontier warrants re-examination, taking place before RAF doctrine was codified, and before strategic bombing became central to the independent RAF.

[4]

Handley Page V/1500 heavy bomber, ‘

Old Carthusian’, pictured in India in March 1919 after completing the first UK-India flight in January of that year. In May 1919, this aircraft bombed rebel Afghans in Kabul, and was thus the only V/1500 to see action. © Crown Copyright / Ministry of Defence. Courtesy of Air Historical Branch (RAF).

Jihad

Historians are divided as to

why Amanullah declared Jihad and sent the Afghan Army into British India on 3 May 1919 to start the Third Afghan War, known in Afghanistan as the War of Independence.

[5] British India and Afghanistan had been at peace for forty years since the

Treaty of Gandamak ended the Second Afghan War in 1879 and ‘we [the British] gave Afghanistan a stiff subsidy, and in return claimed the right to control its foreign relations’. Yet:

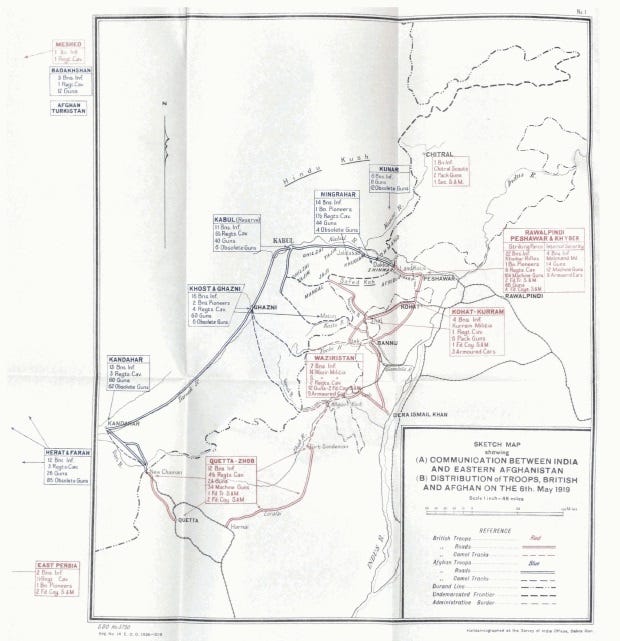

The Afghan Army of around 50,000 men, supported by up 120,000 more from the frontier tribes, invaded British India on four fronts, as shown in Figure 1, from Dakka towards the Kyber Rifles’ base at Landi Kotal and the Khyber Pass, from Khost towards Kurram and Waziristan, from Spin Baldak towards Quetta in Baluchistan, and minor operations into Chitral. In response Britain deployed up to 340,000 men and 185,000 animals, but many of the best troops were overseas, during what the historian Keith Jeffery called the

Crisis of Empire. British forces were facing rebellion in Ireland, intervention in Russia, and garrisoning occupied territories in Germany, Turkey and the Middle East. It was also a period of great uncertainty for the RAF, shrinking from 285,000 all ranks in November 1918 to 35,000 by the time the Treaty of Rawalpindi ended the Third Afghan War on 8 August 1919. Moreover, disturbances in the Punjab had culminated in the killing of 379 Indian civilians at Amritsar on the orders of Brigadier General Reginald Dyer.

[7] Many of the British and Indian troops deployed to the Indian frontier were either awaiting demobilisation or were untrained recruits. Additionally when Amir Amanullah declared

Jihad, many British tribal levies and frontier militias mutinied or switched sides, which resulted in some units, such as the famous Khyber Rifles, being disbanded.

[8]

Figure 1. General Map, Distribution of Troops, 6 May 1919. © Crown Copyright.

[9]‘Co-operation of Aircraft with the Army’

Contrary to popular perception, the British Indian Army had long recognised the value of air power. Lieutenant General Douglas Haig, when Chief of the General Staff India, had been impressed with an air demonstration in 1910, and an Indian Flying School had been established by 1913.

[10] No 31 Squadron Royal Flying Corps had arrived in India on Boxing Day 1915 and as soon as the squadron reached North West Frontier Province, Sir George Roos-Keppel, the Civil Commissioner since 1908, had the the aircraft flown at a durbar to demonstrate to the tribal

maliks the newly arrived air power, and take him for a flight as well. In November 1916 twelve 31 Squadron aircraft took part in operations against the Mohmand tribe near the Khyber Pass and against the Mahsuds in Waziristan in 1917.

[11] When the Afghans crossed the border on 3 May 1919, No 31 Squadron RAF were General Sir A A Barrett’s North West Frontier Force’s (NWFF) ‘corps’ squadron. Two B.E.2c aircraft were placed at readiness to support Barrett’s two infantry divisions and four brigades. Lieutenant Colonel F F Minchin DSO MC RAF, commanding the 52nd (Corps) Wing RAF at Murree, went to Peshawar to confer with Barrett and Major E L Millar MBE RAF, officer commanding 31 Squadron, was attached to the NWFF as liaison officer.

[12] No 114 Squadron was the Army reserve at Quetta, with one flight attached to the corps sized Baluchistan Force.

A Royal Air Factory B.E.2c. © Crown Copyright / Ministry of Defence. Courtesy of Air Historical Branch (RAF).

Nos 31 and 114 Squadrons were employed in tactical

air power roles that had been employed successfully on the Western Front, though with a much smaller force density.

[13] Unfortunately Nos 20 and 48 Squadrons RAF, flying the more capable Bristol Fighter, arrived too late to take part. There was no Afghan air force but control of the air was contested by accurate ground fire, exacerbated by the 10,000 feet ceiling of the B.E.2cs, which meant they were often flying below the tribesmen, whose marksmanship was renowned. On 9 May three aircraft were shot down, although all three landed behind British lines. Another crew were returned, unharmed to Peshawar by Afridi tribesman after a forced landing in the tribal area, for a reward of 30,000 Rupees. On the Waziristan front, in response to air actions, over fifty tribesmen raided Bannu aerodrome and were beaten off without damaging any aircraft.

[14]

The RAF flew aerial reconnaissance sorties over the Khyber front from Risalpur (now the Pakistan Air Force Academy) from 6 May but Nos 31 and 114 Squadrons between them flew only four artillery co-operation flights and two contact patrols during the campaign, presumably because of the difficulties of identification in the terrain. Instead the bulk of the 693 hours flown were in the attack role, dropping 21 tons of bombs and firing 9315 machine gun rounds, either in pursuit or on enemy concentrations, both recognised Army co-operation roles in the evolving RAF doctrine of the day.

[15]

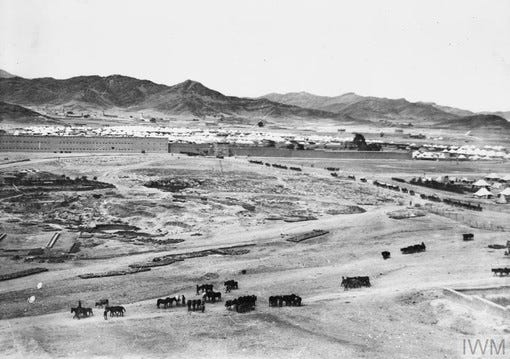

Landi Kotal fort and encampment in the Khyber Pass; the 1st (Peshawar) Division’s forward base for operations against the Afghan Forces. © IWM (HU 74435).

The first recorded air attacks were during the British counter-attack at Bagh near Landi Kotal on 11 May to drive the Afghans away from the Khyber Pass, the

Official History reporting ‘[the RAF] followed the flying [retreating] enemy and took toll of them by bombing and machine gunning groups of the fugitives’.

[16] Two days later the RAF attacked the Afghan Army concentration at Dakka, ten miles north-west of Landi Kotal, where 1½ tons of bombs and 1151 machine gun rounds inflicted 600 casualties, including the commander, a tribal

malik and mullah, causing the Afghans to: ‘to evacuate their camp and retire hastily in the direction of Jalalabad. The Mohmands from the left bank of the Kabul river looted and carried away whatever they could lay their hands on.’

[17]

Field gun of ‘M’ Battery, Royal Horse Artillery, in action against snipers at Dakka, 15–17 May. © IWM (HU 74438).

On 17 May all available aircraft bombed a concentration at the city of Jalalabad, 37 miles north west of Dakka:

The air attack was repeated on 20 and 24 May, when parading Afghan soldiers were bombed and parts of the city set on fire, and was believed to have convinced the enemy force to withdraw.

Aircraft were redeployed from Risalpur to Kohat on the Kurrum front on 26 May — to support the British brigade

besieged at Thal by the Afghan Army and

Waziris — and commenced bombing Afghan artillery on 28 and 29 May. Four aircraft successfully co-operated with the Thal relieving column, commanded by the soon to be dismissed General Dyer, and dispersed a body of 400 Zaimukhts ‘with bombs and Lewis gun fire’ on 1 June.

[19]

Meanwhile on the southern front aircraft availability was limited and there was the only recorded case of fratricide. The two available aircraft were wrecked on 10 May in landing accidents. They were either repaired or replaced as No 114 Squadron was able to bomb

Spin Baldak Fort before British troops stormed it on 27 May, but in doing so hit advancing troops:

‘Independent Operations’

Halley’s raid on Kabul was remarkable both for its effect and the circumstances leading to it, and appears to have been his own initiative, truly ‘Independent Operations’. Both the V/1500 and the Vickers Vimy were produced to meet an Air Board requirement of 30 July 1917 to bomb deep into Germany, in response to the German Gotha raids on London which had led to the

creation of the Royal Air Force.

[21] The V/1500s first planned operational sortie was for three bombers of No 166 Squadron RAF, No 27 Group, Independent Force at Bircham Newton, to bomb Berlin and fly onto Prague. The raid, however, planned for 8 November 1918, was delayed by unserviceability and then the Armistice with Germany.

[22] One of these aircraft,

Old Carthusian, was subsequently the first aircraft from Britain to fly to India, flown by Major A C S Maclaren and Halley, with Brigadier General N D K MacEwan as passenger,

[23] and fitters Flight Sergeant Smith and Sergeant Crockett and rigger Sergeant Brown, all the crew receiving Air Force Crosses or Medals. Taking off on 13 October, it flew via Rome, Malta, Cairo, and Baghdad, and reached Karachi on 15 January 1919, and Delhi in February. In March the aircraft was parked in the open at Lahore, unmaintained, waiting to be dismantled before being displayed in a Delhi Museum.

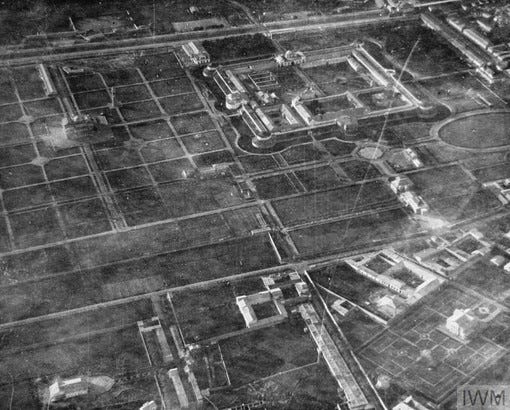

Aerial view of part of Kabul taken from Handley Page V/1500, J1936,

HMA Old Carthusian, during its bombing raid on the Afghan capital, 24 May 1919. © IWM (HU 74444).

When the Afghan war started, Halley volunteered to raid Kabul using the Handley Page O/400 Brigadier General A E (Biffy) Borton and Captain Ross Smith intended to use for the first flight from India to Australia. Halley had flown night bombers with Britain’s first strategic bombing force, No 3 Wing Royal Naval Air Service, from Luxeuil in 1917, and had won two Distinguished Flying Crosses (DFC) flying O/400s with No 216 Squadron RAF, Independent Force, in 1918.

[24] After Halley flew it to Risalpur in preparation Borton’s O/400 was destroyed in dust storm. MacEwan, now General Officer Commanding RAF India at General Headquarters Simla, seemingly on his own initiative and with no previous involvement in ‘Independent Operations’, sent Halley back to Lahore to investigate restoring

Old Carthusian. The mainly Indian staff at the Lahore Aircraft Park, aided by the Government Railways and Wagon Works and Halley’s fitters and rigger, skilfully restored the aircraft, even making two laminated four bladed propellers from local Padauk wood. Four 112 lb bomb racks replaced the originals that had been removed, and a further sixteen 20 lb bombs were carried in the cockpit.

[25]

A Handley Page O/400 bomber. © Crown Copyright / Ministry of Defence. Courtesy of Air Historical Branch (RAF).

Halley took off at 0300 hours on 24 May, and flew up the Khyber Pass towards Kabul with a volunteer observer, Lieutenant William Villiers, and Smith, Crockett and Brown. They pressed on despite an engine oil leak, just clearing the 8,000 feet Jagdalak pass, bombed Kabul and landed at Risalpur six hours later. Halley was awarded a second bar to his DFC, though his crew were not commended. Halley was also one of the 1005 of the 6500 applicants to be granted a permanent commission in the RAF in 1919.

Conclusion

The war cost 1,329 British and Indian servicemen killed and wounded and 566 dead from cholera and a further 1653 hospitalised. Neither Halley or the RAF ‘ended the war on [their] own’ but the importance of air power was widely recognised. When on 3 June the Viceroy Lord Chelmsford granted Amir Amanullah the armistice he had requested, he assured him British aircraft would not attack Afghan ‘localities or forces’ but would have the freedom to overfly Afghanistan to ensure the armistice was complied with. The aircraft were not to be shot at and the Amir was to ensure the safety of any aircraft and airmen forced to land.

[26] Recognising the potency of air power, Amanullah created his own air arm from 1921.

The bombing of Kabul was controversial. While the British Commander-in-Chief thought Halley’s ‘raid was an important factor in producing a desire for peace’ in the Afghan Government,

[27] the Amir complained to the Viceroy that the British were like the Germans:

The New Statesmen also considered the Kabul raid illegitimate: ‘we retaliated by aeroplane raids on Kabul and by the more legitimate use of our air power to bomb and disperse armed gatherings of Afghan troops.’

[29] Nonetheless, Halley’s raid demonstrated the RAF’s intrinsic belief in the ‘morale effect’ of ‘Independent Operations’ before it was established in Trenchard’s policy.

[30]

Alas, the potential of air power on the frontier demonstrated in the

Third Afghan War was never fully realised, as several recent

Air Power Review articles have argued, because of limited Government of India funding and Indian Army rather than Air Ministry authority, notwithstanding efficient tactical Army and RAF co-operation in numerous frontier campaigns.

[31]

Biography: John Alexander is a historian at the RAF’s Air Historical Branch and an RAF Reserve. As a regular he specialised in air/land integration, including in the Falklands and various Middle Eastern campaigns, was twice a Chief of the Air Staff Fellow, conceptualised future conflict for the 2010 Strategic Defence and Security Review, and spent 2011–2017 serving in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

By Group Captain John Alexander

medium.com