Living insecure and lonely

by Monwarul Islam | Published: 00:05, Nov 16,2017 | Updated: 01:04, Nov 16,2017

WHILE talking to a doctor friend of mine, who is pursuing a higher degree in psychiatry, about a few days ago, I was astonished to find his cutting, edgy observation on the state of mental health of urban people who, in his words, are thronging the chambers of psychiatrists.

He answered callously, when I asked him for the reason behind his pursuing higher degree in psychiatry, that the business of psychiatrists is booming as more people are suffering from different types of mental health issues.

To my further question why people are becoming more vulnerable to psychiatric problems, the would-be psychiatrist said, to summarise, that most of us are living with a compulsive and consistent sense of insecurity and loneliness.

His cold and calculated answers, thrown a bit jokingly though, got on my nerves.

What he said is wholly true that we, hundreds of thousands, are living with a destabilising sense of insecurity, economic and otherwise,

and we are living lonely amidst the crowd.

For a psychiatrist, this might mean a business prospect, to joke a little,

but it sheds light on a far deeper condition of our social and personal life.

With our social lives torn and tossed, family ties severed or atomised, with precariousness being the defining factor of our economic state, with distrust having its toll on interpersonal relations, we are pushed to create shells around our private-personal lives and lock ourselves inside them.

Out of these shells, we can no longer maintain real social contacts;

neither can the ethereal ones provide us with the needed warmth of togetherness.

As the would-be psychiatrist puts it — people are becoming more insecure and lonely and these two conditions define our hectic lives.

Insecurity, as the word suggests, is lack of security, of stability, of a belief that you are in a firm position and have nothing to fear. Sadly we are living in a society where economic and political system is so designed as to fill us inevitably up with a sense of insecurity.

The deepest sense of insecurity, for today’s urban people without a war to threaten their lives, is of the economic insecurity.

Well over a half of the working people in urban areas are insecure about their jobs, their income. Their income and their jobs are, at best, precarious. They have nothing or very little to stick to which can give them an identity, a profession-based identity.

You are hired today to do a job; you will be fired tomorrow if your service is not needed. As a result, both of your profession-based identity and profession-generated skills are highly unlikely to sustain. As such, your attachment to the work you do is at best extraneous and fragile.

You are nothing more than a ‘mechanistic part’ in your workplace. The part you serve in your office or at work does not necessarily require the individual you. In such a condition, a worker’s position is definitely vulnerable and prone to exploitation and is bound to develop a riding sense of insecurity.

The authorities will surely take the best advantages of this situation. They will make you work more and pay less. They will decide whether you are secure with them or not.

In fact, the number of workers and officials with insecure, precarious jobs, not to mention the large number of the unemployed and the underemployed, is so fast increasing that a class which economist like Guy Standing and some others have named the ‘precariat’ appears to be in the making.

Standing’s 2011 book

The Precariat: the New Dangerous Class defines this class as a mass one characterised by chronic uncertainty and insecurity.

Due to what the neoliberal, global market terms as ‘job/labour market flexibility’, which is in Guy Standing’s words, ‘an agenda for transferring risks and insecurity onto workers and employees’, there has been the creation of a global ‘precariat’, composed of many millions around the world without an anchor of stability.

The descriptive term ‘precariat’ came into use in the hands of French sociologists during the 1980s, but seeing it as a class, or class-in-the-making as Guy Standing puts it, in the globalised era began very recently.

Not to go deeper into Guy Standing’s elaborate and interesting stratification of the new class orders under the globalised economy, it is quite understandable that more people are being trapped into this precarity where chronic insecurity is the staple condition.

While writing on the range and volume of the class, Noam Chomsky, one of the leading thinkers of today, in his 2012 article ‘Plutonomy and the Precariat’,

goes as far as to say that except the handful wealthiest with access to power and control over politics and policies the whole lot of the rest are in the precariat, living their lives adrift and unstable.

With no sight of sustainable development of life and career, with no let-up from the gnawing sense of insecurity, this class is led to live a life characterised by

alienation, anger, anxiety and anomie. Guy Standing succinctly says, ‘a life with four A’s’.

Needless to say that a person of this class who experiences these four A’s is a lonely, alienated and detached man fighting his dogged fights round-the-clock to keep his fears at bay.

Since the system, in its mechanic-systemic pull, is throwing us into a space of hostile competition and compulsive individualism where one’s gain inevitably makes others’ at stake, where we are in a war of every man against every man, we are losing the good-old values of living together.

One can quite logically remember, in this connection, Karl Marx’s path-breaking explanation of alienation which explains workers’ alienation from their labour, from their productions, from each other and, most importantly, from their species-essence (guttungswesen).

The last aspect of alienation, that is, alienation from what Marx termed guttungswesen (translated as species-essence or human nature) in his

Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 (also known as the Paris Manuscripts) is related, in effect, to the other three aspects of alienation; and alienation from the ‘species-essence’(the natural way of living) is what turns, to be more accurate forces, the human nature into a mechanistic part in the mode of production.

Society, as we understand it, is not any more a working concept as social spaces, meaning spaces of inter-personal communications and sharing, are just vaporising. Instead of social spaces, we are driven into a sort of a distorted private space where as persons we are inhabited by deep-rooted sense of insecurity and loneliness.

Since the fundamental characteristic of humans as mammals with a history of shared living is no more with us, we are carrying wounded, irreparably damaged private lives making us prone to psychosis of one sort or another.

It is, therefore, no wonder that, according to a national survey, 16 per cent adults in the country, specially the urban adults, are suffering from some sort of mental health issues and, the doctor friend says, the number is increasing.

Monwarul Islam is a cultural correspondent of New Age.

http://www.newagebd.net/article/28424/living-insecure-and-lonely

12:00 AM, October 29, 2017 / LAST MODIFIED: 05:35 AM, October 29, 2017

Get good governance

Bangladesh needs strong control structure for planned urbanisation, tell speakers at an int'l conference

Jatiya Sangsad Speaker Shirin Sharmin Chaudhury speaks at a conference titled “Cities Forum: Building Knowledge Networks and Partnerships for Sustainable Urban Development in Bangladesh” in a Dhaka hotel yesterday. World Bank, Municipality Association of Bangladesh, Institute of Architects Bangladesh, Bangladesh Institute of Planners, and Institution of Engineers, Bangladesh organised the two-day programme beginning on the day. Photo: Star

Staff Correspondent

Strong governance is the key to planned urbanisation in Bangladesh, said urban experts from home and abroad at an international conference in Dhaka yesterday.

“The current governance structure is not conducive for Dhaka to become a liveable metro city,” said Balakrishna Menon Parameswaran, lead urban specialist of the World Bank, adding, “Combination of leadership, planning and investment, and meaningful consultation is required for transforming Dhaka into a liveable city.”

Lack of proper policies or wrong policies or a combination of both was holding back the desired urbanisation in Bangladesh, he said. In an unprecedented event, 20 lakh people moved into Dhaka in the last five years, he said.

The World Bank, Municipality Association of Bangladesh, Institute of Architects Bangladesh, Bangladesh Institute of Planners, and Institute of Engineers Bangladesh jointly organised the two-day conference on “Cities Forum: Building Knowledge Networks and Partnerships for Sustainable Urban Development in Bangladesh” at the Dhaka Sonargaon Hotel.

Balakrishna underscored the need for empowering the elected city mayors.

“Strong urban governance is what we need,” said Rene Holenstein, the Swiss ambassador to Bangladesh.

Qimiao Fan, World Bank country director, said only well-managed urbanisation could lead to sustainable economic growth, allowing productivity and innovations.

In recent years, Bangladesh has experienced an annual urbanisation growth of 3.3 percent with 5.4 crore people living in the urban centres and the number is predicted to double in the next three decades or so, he said.

Urban areas contribute 60 percent of the country's GDP, and Dhaka and Chittagong together share 47 percent of the total output, Fan said.

This urbanisation is expanding job and manufacturing opportunities, he said, adding that more work was needed to fully capture the enormous benefits of urbanisation.

Bangladesh needs to address the critical challenges brought about by the massive unplanned urbanisation, characterised by high-level poverty, and generally poor housing conditions and liveability.

More than one out of five urban dwellers in Bangladesh lives in poverty, Fan said.

According to Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, nearly 62 percent of the urban population, which is about 3 crore people, currently live in informal settlements and slums.

The country's urban centres need a minimum of $2 billion annual investment for basic infrastructure, such as roads, water and sanitation, to meet the demand of the rapidly growing urban population, Fan said.

In Bangladesh, only three percent of the total public expenditure is on urban infrastructure development, which is very low by global standards. Bhutan spends 16 percent, Nepal 10, Indonesia 34 and South Africa 52 percent, he said.

Dhaka South City Corporation Mayor Mohammad Sayeed Khokon said lack of adequate urban planning has led to today's civic woes, traffic congestion and flooding.

Narayanganj City Corporation Mayor Salina Hayat Ivy said there had always been an effort to keep the local government institutions submissive.

“We as the elected mayors cannot exercise the power provided by the present law and cannot play our mandated roles,” she said.

Different municipalities have different problems and the government needs to address them separately, she said.

Md Akter Mahmud, a professor at the department of urban and regional planning of Jahangirnagar University, pointed out several challenges in urban planning in Bangladesh.

He said Dhaka became the centre of politics, employment, amenities and facilities. “Every year 100,000 people are being added to existing population,” he said, adding that 41 percent of total urban population live in Dhaka.

“Local bodies are not equipped or do not have the technical and financial strength. They also do not have the visionary leadership,” he said suggesting that mayors of municipalities increase income generation capabilities instead of depending on funding from donor agencies and the government.

Akter said every year the country loses one percent of arable land due to unplanned urbanisation.

Robert Cervero, a professor at the department of city and regional planning of the University of California, urged focusing on Dhaka's transportation problems.

He said, “Yes, we need flyovers but there has to be other facilities and strategies to address the city's transportation problems.”

He emphasised the need for introducing mass transportation facilities to curb traffic congestion.

Ralph Becker, former mayor of Salt Lake City, Utah, said galvanising collaboration among all stakeholders with a common goal of public good is what a mayor could facilitate.

Chief guest Speaker Shirin Sharmin Chaudhury said a comprehensive approach of professional groups and experts was needed to address the complex urbanisation issue.

Md Abdul Baten, president of Municipal Association of Bangladesh, chaired the inaugural session in which 300 mayors, councillors and urban practitioners took part.

Mel Senen S Sarmiento, who had been the mayor Calbayog city of the Philippines for nine years, also spoke on the occasion.

http://www.thedailystar.net/frontpage/get-good-governance-1483120

Time to act on Dhaka city

Salma Khan

Update: 17:57, Oct 29, 2017

It has long been acknowledged that the capital city Dhaka is hardly livable. Any adverse happening in the country has a serious impact on Dhaka.

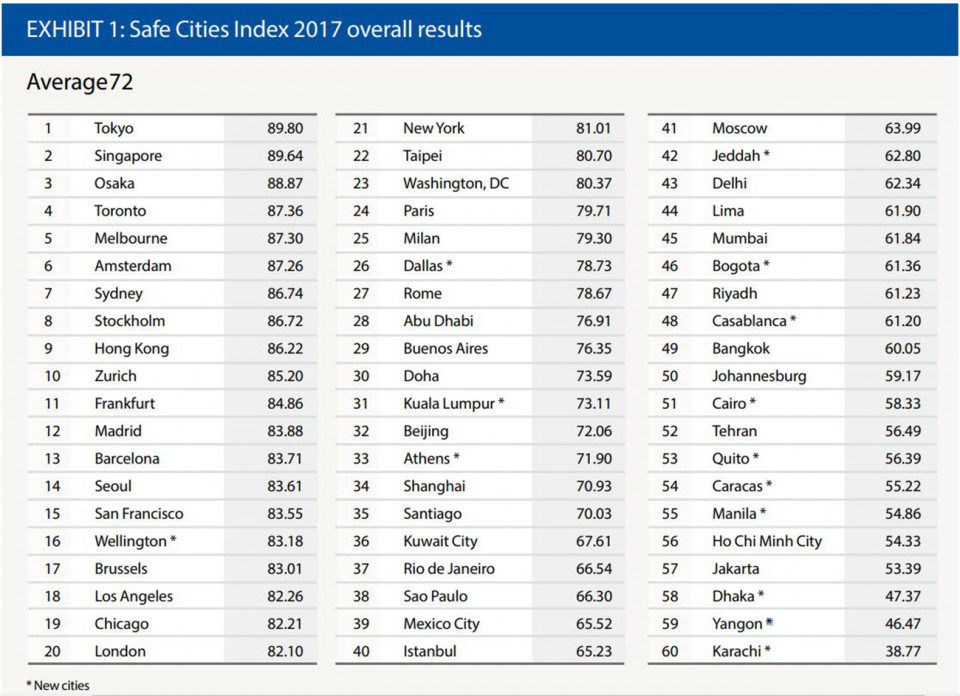

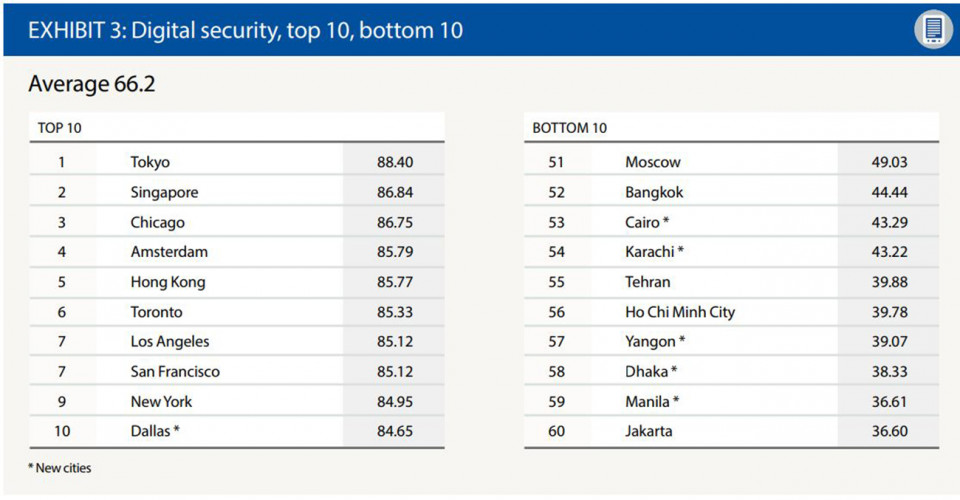

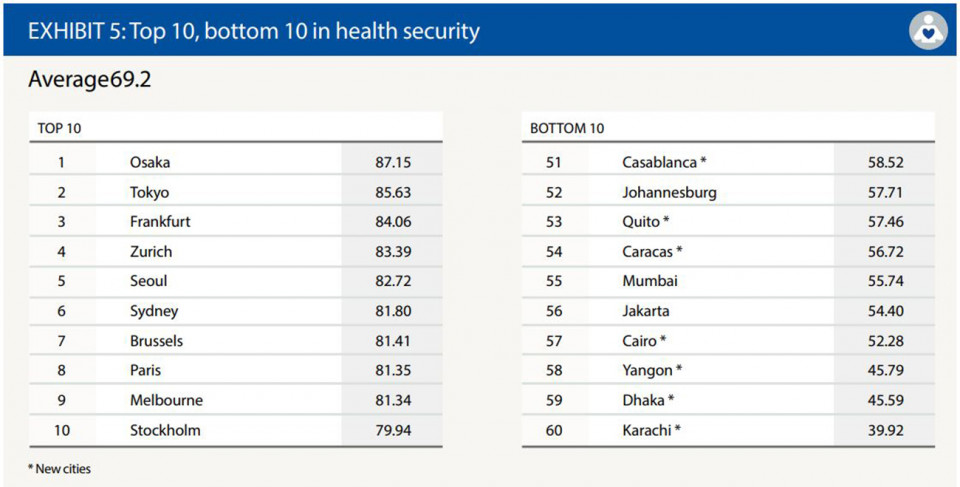

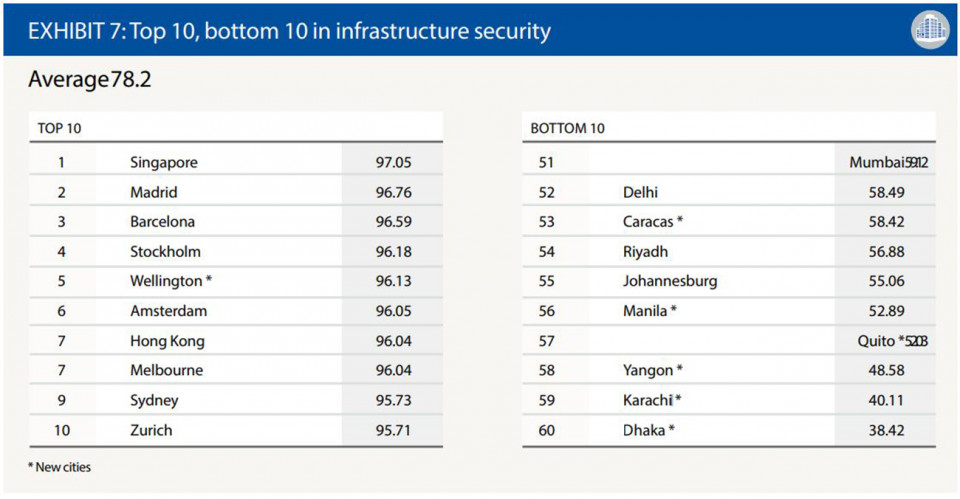

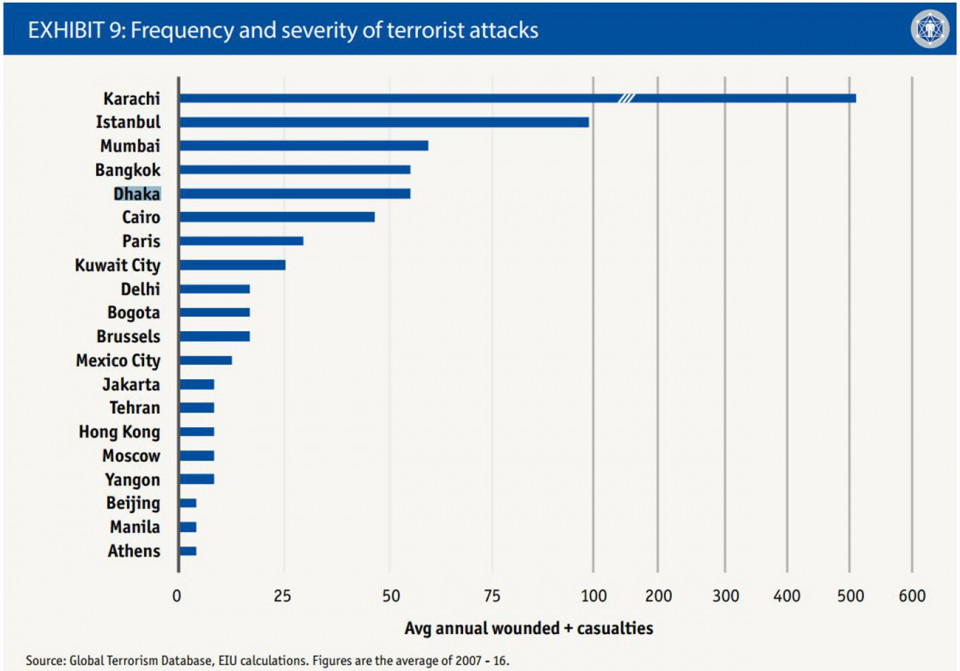

According to a survey of the Intelligence Unit of The Economist, Dhaka is the third most unlivable city in the world.

In context of insecurity for women and also sexual violence against women, Dhaka is in fourth position. Dhaka is also has a high level of physical and mental stress.

According to a survey of health journal Lancet, Bangladesh tops the list of deaths for environmental cause.

In different indexes of living standards, Dhaka is steadily deteriorates.

In this backdrop, Prothom Alo in its editorial had asked, "When will those concerned wake up and act?”

The government hopes to become a middle income country by 2030 through the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). UK-based research centre PWC predicts that this is possible as the GDP growth rate is consistently upward in our country in comparison to other developing countries. So why is the capital of this country in such a bad shape?

Villages were at the heart of development in the nineties. Given the indicators of social development including reduction of poverty, child and mother mortality and population at the village level, Bangladesh became a role model of development.

Dhaka became the centre of development. The government and the private sector mostly invested in Dhaka. As a result, people from different districts moved to Dhaka in search of employment, education and health services.

Although there are district-wise projects under different ministries, they are not properly implemented. As a result, the pressure ultimately falls on the infrastructure and civic amenities of Dhaka.

Such extreme pressure leads to unplanned expansion, grabbing, violence, accidents, stealing, robbery, snatching and mismanagement in traffic system.

All this contributes to serious traffic congestion in Dhaka.

Women's insecurity is also increasing.

Dhaka is a mega city due to increased population and high demand for a life standard. It is not surprising that Dhaka is low on the list of livable cities.

The government and the residents of Dhaka have to properly act. It is the responsibility of all to turn our beloved Dhaka into a livable city. The local government, the deputy commissioner, the mayors, and the law enforcing agencies have to play a key role.

Quality education and employment opportunities for young people have to be created outside Dhaka if the pressure on Dhaka is to reduce. According to UNICEF, 7,100,000 youths aged between 15 and 17 are outside of the education system. In order to create employment for them at a local level, they have to be provided education, especially technical education at a district level. The education ministry and the health ministry have to allocate funds accordingly.

The huge number of vehicles is not the main cause of traffic congestion in Dhaka. It is violation of the traffic rules that mainly causes traffic congestion. The traffic rules should be enforced strictly. Due to violation of traffic rules, Bangladesh is on top of the list when it comes to road accidents.

In mega cities like Singapore and Jakarta, vehicles are controlled strictly. In Jakarta, every car has to have at least three passengers or they have to buy tokens.

In Singapore, cars with even numbered licence plates move one day and odd number cars on the alternate days. Otherwise, they have to pay extra.

Emphasis has to be given on education, health and employment to turn Dhaka into a livable city. Education and health services have to be expanded.

Employment opportunities have to be decentralised.

In the eighties of last century, the government declared that some special ministries and departments would be shifted outside Dhaka.

These were the shipping ministry, the railway ministry, and the labour and employment ministry.

Still such steps can be taken so that development takes place in other areas of the country and young entrepreneurship is created.

Dhaka will have to be turned into an able mega city to provide all sorts of social, economic and civic amenities as we achieved independent Bangladesh at the sacrifice of three million people. Dhaka will be number one on the list of livable cities. For this, all concerned have to act now.

Salma Khan is an economist and women’s leader.

*This piece, originally published in Prothom Alo print edition, has been rewritten in English by Rabiul Islam.

http://en.prothom-alo.com/opinion/news/164737/Time-to-act-on-Dhaka-city

Bangladesh’s urban underbelly a cause for concern

Abu Siddique

Published at 05:22 PM October 30, 2017

Last updated at 12:52 AM October 31, 2017

Garbage floats on the Rayerbazar canal just outside the Rayerbazar slum in Dhaka

Mahmud Hossain Opu/Dhaka Tribune

About 2.2 million people live in the nation's urban slums as squatters and floating population. This is the first of a three-part series in which the Dhaka Tribune's Abu Siddique explores the rights of slum dwellers, their access to the safety net and basic civic services such as healthcare and sanitation

With a population of 160 million, Bangladesh is gradually moving towards middle-income status with many people’s fortunes rising because of trade and industrial activity in cities like Dhaka and Chittagong.

However, the growth of such urban centres has come at a cost, with urban sprawl and rapid rural-to-urban migration putting a strain on infrastructure and services.

“We are gradually doing a lot of things to improve the conditions in the slums but because the number of people keeps rising every day, it is hard for us to keep up,” Slum Development Officer of Dhaka South City Corporation, A K M Lutfur Rahman, said.

The annual population growth rate recorded in the 2014 Census of Slum Areas and Floating Population was 2.70%. This has created a housing issue where most of the urban poor have ended up living in slums that are not equipped with basic facilities such as safe drinking water, sanitation and healthcare.

“The absence of a coordinating mechanism between the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare and the Ministry of Local Government is increasing the problem,” said Prof Nazrul Islam, a leading slum specialist.

The 2014 census recorded a rise in the number of slums in Bangladesh from just 2,991 in 1997 to 13,935 slums in 2014.

These were home to 2,232,114 people, or 6.33% of the urban population of the country.

The census found that 52.5% of households in Bangladesh sourced their drinking water from tube wells, while 45.2% of households had tap water.

In city corporation areas of Dhaka, 55.1% of slum dwellers got their drinking water from taps and 42.5% got their drinking water from tube wells.

In stark contrast, 87.6% of slum dwellers in municipal areas got their drinking water from tube wells whereas only 10.3% of households had taps. About 5.7% of slum dwellers sourced their water from ponds or ditches.

“It is very unfortunate that there are still a lot of people who are living without fresh drinking water,” Khairul Islam, country director of WaterAid Bangladesh, said.

House inside the Rayerbazar slum in Dhaka – Mahmud Hossain Opu/Dhaka Tribune

According to the Urban Health Survey 2013, 32.7% of slums under both the city corporation did not have any government facilities available, while 36.9% of the slums were bereft of community health workers.

Additionally, the Demographic Health Survey 2014 found that the urban poor had little access to healthcare in the slums, where the prevalence of family planning and institutional delivery was 54% and 45.5% respectively.

Of the many health indicators, Bangladesh has significantly reduced the child death rate through measures including a countrywide immunisation programme among children.

Slum children also received the polio vaccine during a national programme introduced by the government. However, the percentage of slum children who received polio vaccine was about 94.9%, compared to universal coverage nationwide.

Brig Gen Md Zakir Hassan, chief health officer of Dhaka North City Corporation, said ignorance is the reason why slum dwellers do not pay much heed to their health workers.

“It often seems as though healthcare officials had to motivate parents to immunise their children or get a checkup when they had a cold,” he said.

The prevalence of latrine facilities is treated as a substantive indicator of a healthy and hygienic environment. Data from the 2014 slum census showed that 42.2% of households used a pit for a latrine, followed by 26.2% using sanitary latrines.

Tin latrines were used by 21.1%, hanging/kutcha by 8.6%, and open spaces by 1.8% on a national level.

In city corporation areas, 42.5% of households used pit latrines, followed by 26% using sanitary (water sealed) latrines. Tin latrines were used by 23.6% of households, hanging/kutcha by 6.8%, and open spaces by 1.8% of households.

In municipal areas, 41.8% of slum dwellers used pit latrines and 28.9% used sanitary latrines, while 14.8% used hanging/kutcha latrines, 10.4% tin latrines, and 4.2% open spaces.

According to the 2014 slum census, the total number of household enumerated was 594,861, of which 431,756 were in the city corporation areas, 130,145 were in municipal areas and 32,960 were in other urban areas. The average household size is 3.75.

http://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/2017/10/30/bangladeshs-urban-underbelly-cause-concern/

Urban poor often overlooked for social safety net programme

Abu Siddique

Published at 02:30 AM November 01, 2017

Last updated at 02:33 AM November 01, 2017

File Photo

Of the Old Age Allowance, 94.03% covers the rural poor while only 5.97% goes to the urban poor

Massive imbalances exist in the level of support given to the urban poor and the rural poor under the social safety net programmes (SSNPs) initiated by the government, research by Concern Worldwide Bangladesh has found.

The study showed that among the two major SSNPs – the Old Age Allowance and Widowed and Distressed Women Allowance – there is a vast discrepancy in the distribution of support between the urban poor and the rural poor.

Of the Old Age Allowance, 94.03% covers the rural poor while only 5.97% goes to the urban poor. The Widowed and Distressed Women Allowance is even more lopsided, loaded 98.32% in favour of the rural poor and only 1.68% to the urban poor.

Gazi Mohammad Nurul Kabir, director general of Department of Social services, said the programmes are part designed to reduce the migration of lower income groups to urban areas.

“One of the major intentions of the SSNPs is to provide more support to rural areas (and) that is why the government has been running different programmes as an incentive to have them return to the villages,” he said.

However, the National Social Security Strategy 2015 acknowledges the shortcomings of the safety net programmes and aims to reform the provisions to ensure “more efficient and effective use of resources, strengthened delivery systems and progress towards a more inclusive form of Social Security”.

To give the urban poor as equal access as their rural counterparts, the strategy plans to provide services for the elderly, children, vulnerable women and people with disabilities.

Amela Begum, 50, is originally from Jamalpur but lives in a shanty near Khilgaon flyover and earns Tk2,000 a month working as a maid. Despite living in Dhaka for almost 20 years, she has no idea about the SSNPs that she can access when sick or as a vulnerable woman.

Quazi Shahbuddin, an economist and the former director general of Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies (BIDS), told the Dhaka Tribune: “The reason why people still keep migrating to urban areas might have something to do with finding better employment opportunities. As the government’s resources are limited, it has to choose where the support goes first.”

No permanent address? No NID

There are more than 594,861 people living in slums or are homeless according to the Census of Slum Areas and Floating Population 2014, who by the nature of their living situation are unable to get a National Identity Card (NID) or a birth certificate even though these documents have been made mandatory by the government.

The problem is that Dhaka is home to a large number of migrant workers who usually work in the informal sector and move from one job to another very frequently. Their addresses change along with their jobs.

Ultimately, the children of these people are unable to enroll in school as they do have a birth certificate, which also needs a permanent address.

Razia Sultana and her family has been living in Dhaka for 20 years usually in shanties or on the footpaths. She now lives in a shanti in Maniknagar area and because of this, she cannot acquire a NID or get birth certificates for her children.

“For last three years, my husband and I along with our three children have been living here. I tried to enroll my youngest child, Alamin in school but they refused to take him because he does not have a birth certificate,” she told the Dhaka Tribune.

Because she works from down to dusk, she said they had no idea how to even get a NID.

Director of (operations) of National Identity Registration Wing, Abdul Baten said, according to the law, a permanent address is mandatory when applying for a NID.

“We cannot help people without a permanent address.”

http://www.dhakatribune.com/banglad...often-overlooked-social-safety-net-programme/