Ultimately unless the west can ensure that this time a revived jcpoa will actually deliver on all of its economic promises,then of course its only natural that iran will continue to reorient itself economically ever more towards the east.Indeed I think that even if the jcpoa was revived,that iran would still continue its economic policies of looking eastwards.

East of Eden: Will Tehran find salvation in ‘looking eastwards’?

https://www.clingendael.org/publication/east-eden-will-tehran-find-salvation-looking-eastwards

By Hamidreza Azizi and Erwin van Veen 25 Apr 2023 - 15:44

Welcome to the second edition of our blog ‘Iran in transition’ that tracks different dimensions of the evolution of protests and governance in Iran. In our last blog, we offered four indicators that help map out dynamics that can occur in a situation characterized by repressive governance and widespread social discontent: the quality of state-society relations, the nature of intra-elite dynamics, economic prospects and foreign affairs. In this blog, we examine Iran’s foreign relations with regard to the transitional state the country has entered into since the eruption of the 2022/2023 protests.

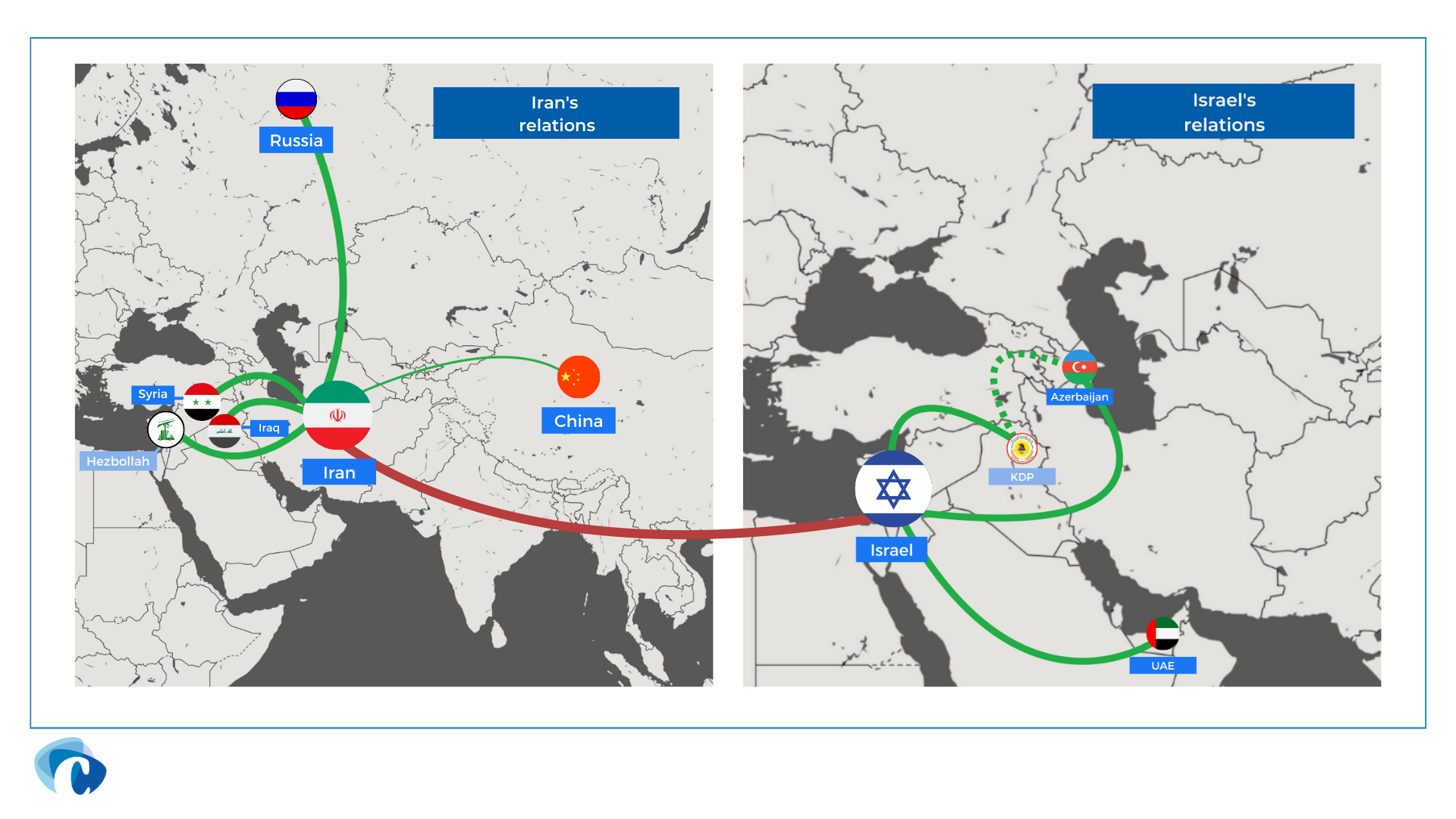

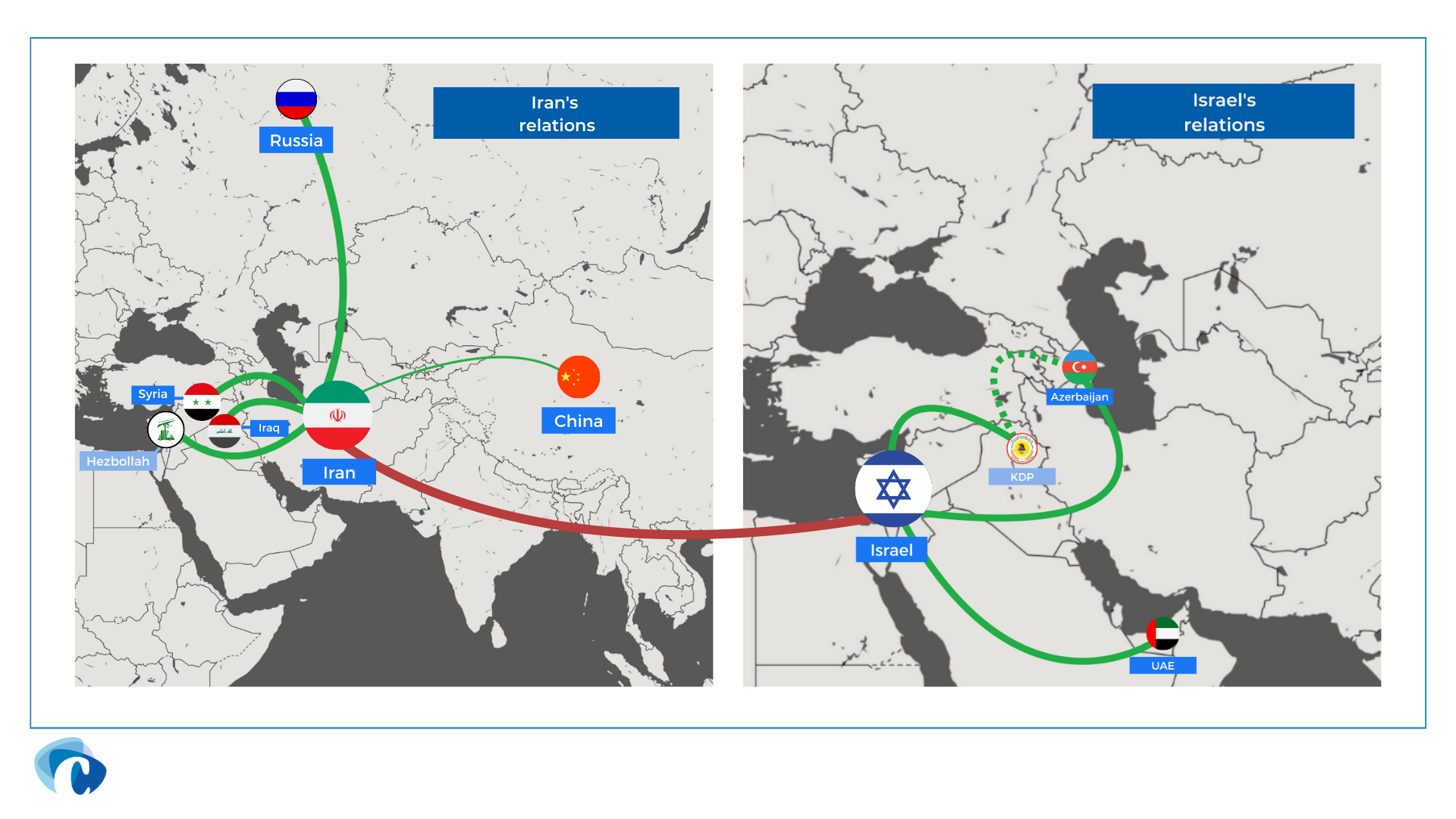

There is a paradox at the heart of Iran’s foreign relations. On the one hand, Tehran appears to feel more confident than ever due to its recent achievement of a number of foreign policy milestones. These include a strategic upgrade of its relationship with Russia, closer ties with China, a newly minted understanding with Saudi Arabia and the absence of consequences for keeping the nuclear negotiations in a dead end. Iran’s ruling elites might be forgiven for feeling they are gaining the upper hand in their geopolitical travails, at least for now. On the other hand, these headline successes obscure significant longer-term economic and geopolitical risks One is the difficulty of achieving economic growth equivalent to the volume that would be possible once US-imposed sanctions were lifted. Another risk are the ramifications of a possible Russian strategic defeat in Ukraine. A third risk is long-term strategic dependence on China as Tehran’s presumed economic savior from US sanctions. Finally, growing ties between the US, Israel, Azerbaijan and the UAE risk constraining Iran’s room for maneuver in its near abroad. But these risks do not seem to be perceived as overly serious in Tehran at the moment.

This situation arguably gives rise to a variation of the ‘Thucydides trap’, as coined by Graham Allison, in the sense that Iranian overconfidence in the strength of its present geopolitical position can lead to a more assertive foreign policy than its true strength warrants. In turn, this can trigger both greater fear and stronger counter-responses from countries like Israel and the United States than what might otherwise occur. We explore the listed factors in turn in order to assess their net geopolitical effect on Iran’s government.

The combination of Western sanctions and Russia’s poor military performance in Ukraine has made Moscow more dependent on Iran to the effect of upgrading Tehran to peer status rather than maintaining it as the junior partner it used to be. Iran has become a key arms supplier to Russia, which is most visible in the large volume of precise, low cost and long range Shahed 131/136 drones. Reports indicate that Iran might be also considering the delivery of ballistic missiles to Moscow. In addition, Russia and Iran are in the process of reviving the north-south corridor to facilitate their trade and connections with India and the Far East. Trade traffic appears to be picking up even though the real expansion of the north-south route remains on the drawing board. Russia now also needs Iran as conduit for industrial inputs it cannot produce itself, such as chips and dual use goods, but also engineering services. The multilateral element of Tehran-Moscow relations has similarly gained in importance over the past year, which is reflected in Iran’s full membership in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and its growing cooperation with the Russia-dominated Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU).

The routes are potential rather than actual. ©Clingendael

To this series of foreign policy achievements, one can add the start of implementation of the ‘Iran-China 25-Year Comprehensive Cooperation Agreement’ in January 2022 (signed in March 2021). Although its contents are shrouded in secrecy, estimates of Chinese investment in Iran in exchange for cheap oil deliverables and consumer good market dominance run into the billions of dollars. The agreement has the potential to bring Iran economic benefits of the same order of magnitude as Tehran’s booming relation with Russia generates in the political-security realm.

Then there is the recent rapprochement between Iran and Saudi Arabia. It reduces the latter’s incentives to join Israeli-US military activity against Tehran and holds out the possibility of realizing a Saudi exit from the Yemen quagmire that Mohammed bin Salman has created for himself at great cost to Saudi Arabia’s international reputation and its Treasury. The recent extension of the cease fire in Yemen until the end of 2023 is indicative that this path might be trodden. While suggestions of large-scale Saudi investment in Iran seem unlikely as long as the US/EU sanctions regime is in force and Iran’s banking sector remains high-risk, Riyadh could start by modest investments in non-sanctioned industries, purchase Iranian oil under the radar and resell it as a service to Tehran, or simply facilitate its export. Yet, even though the ‘deal’ is best seen as a small step in a difficult and far longer confidence-building trajectory, it nevertheless set a different tone in the relationship. It can also open the door for Iran to improve its relations with other Arab states, like Bahrain and Egypt.

Finally, irrespective as to whether some form of a revised or truncated nuclear deal is concluded, Iran does not currently feel much pressure of keeping the negotiations in limbo. In other words, Tehran does not perceive a need to make concessions – especially if the political and economic promises of deeper relations with Russia and China will show more tangible benefits in the near future. Despite growing war talk in some quarters, Iran is well aware that Israel cannot mobilize an adequate assault without US help and that even the US has no credible plan beyond a full scale war that requires weeks of prior deployment to amass the force necessary just to take out Iran’s air defenses. This would inevitably result in a regional conflict and likely accelerate Iran’s pursuit of nuclear weapons. In turn, it would distract Washington from Russia and China as strategic priorities. Otherwise put, it is more convenient to (pretend to) keep talking.

On balance, Iran’s ruling elites are likely to perceive that their alliances have become stronger while threats against them have diminished. The country’s longstanding revolutionary slogan “neither East nor West” encapsulated its desire to conduct an autonomous foreign policy. Within the confines of this slogan, Iran’s more conservative and hardline ruling elites have traditionally been more inclined to ‘look east’ in the tradition of Jalal Al-e-Ahmad’s 1962 treatise on ‘Westoxification’. Now that these elites fully dominate the Islamic Republic of Iran - after the Guardian Council excluded reformist and moderate elites from running during the 2021 presidential and parliamentary elections – they are trading the old slogan for a new ‘look east’ policy. Yet, the payoff they expect from this policy shift overlooks major risks.

One such risk is that the economic benefits of deeper relations with Russia and China will be hard to realize. In the case of Russia, this is because the Iranian and Russian economies are structurally fairly similar, which constrains the achievable volume and limits mutual benefits. Moreover, turning the north-south corridor into a trade highway requires billions in hard infrastructure investment, agreement on a range of soft infrastructure measures between the countries involved (like non-tariff barriers to trade), a coherent national infrastructure plan and years of works and upgrades. This is not impossible, but it will take time that will defer benefits to the medium-term.

In the case of China, it is hard to see investment in the order of hundreds of billions materialize as long as US sanctions remain in place. Investing such sums requires involvement from large, state-linked Chinese enterprises that typically also do business in Western countries and hence risk running afoul of the sanction regime (given Moscow’s own sanction predicament, Iranian trade and investment with Russia would remain sanction-depressed even if those on Iran were lifted). The economic depth that Iran-China relations can achieve thus depends on the extent of Beijing’s willingness to violate US sanctions at a greater scale. Such appetite is likely to be limited. Iran’s recent deal with Saudi Arabia will face the same cost/benefit calculus.

Another risk to Tehran is a Russian strategic defeat in Ukraine. Should Moscow not manage to make progress in the current war of attrition but suffer further reversals instead, the prospect of a domestic backlash, or even political change, in Russia cannot be excluded. Such a turn of events would jeopardize many of the benefits of the upgraded Iranian-Russian relationship. Russia already has had to face significant blows to its reputation for military prowess, the combat readiness of its armed forces and the state of its economy, even though the latter have been more gradual and manageable than many had assumed. But if the US and EU Member States remain steadfast in their support for Ukraine, strategic defeat is a possibility. In this regard, the endurance of EU policy cohesion and the US 2024 elections are critical over-the-horizon indicators. Either way, Iran appears to have underestimated the relevance of the war in Ukraine to the EU with the effect that the possibility of a rapprochement between Tehran and Brussels will remain off the table for quite some time to come, irrespective of the course of the war on the battlefield.

Selected foreign relations of Iran and Israel.

A final risk consists of deepening ties between the US and Israel on the one hand, and the KDP-led part of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, Azerbaijan, Bahrain and the UAE on the other hand. The intelligence on Iran that can be gleaned from such ties might not just enable sabotage operations within Iran but, more dangerously, be used to counter sanction evasion. Greater sanction enforcement is, after all, a low-cost method for the US to contain Iran and encourage domestic unrest. At the very least, closer ties could discourage future trade with, and investment in, Iran by the Arab countries of the Persian Gulf and the Levant. Zooming out, one can also view Iran as being increasingly subject to Israeli strategic encirclement, replicating Tehran’s own longstanding policy towards Tel Aviv via the likes of Hezbollah and Hamas. Iran’s efforts to improve relations with its Arab neighbors are unlikely to convince these states to sever their growing ties with Israel since they simply seek to hedge their positions. In other words, Israel will exercise long-term influence on Iran’s direct security environment, which is likely to give the Islamic Republic a persistent security headache.

Yet, none of these risks seem to be perceived as overly serious in Tehran at the moment. As a result, its foreign policy establishment – the Supreme Leader, his office and the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps – appear to be in a buoyant mood. Linking this back to domestic unrest and protests, such sentiment is unlikely to tempt Iran’s ruling elites into making any concessions to those on the streets, or to feel pressure in having to make concessions in the nuclear deal negotiations due to domestic protests. In its thinking as sketched out above, Tehran rather expects a substantial economic payoff in the short-term from the deepening of its north- and eastbound relations. At best, a sense of foreign policy success might make Iran’s ruling elites sufficiently confident to be more permissive of future protests and dissent.

East of Eden: Will Tehran find salvation in ‘looking eastwards’?

https://www.clingendael.org/publication/east-eden-will-tehran-find-salvation-looking-eastwards

By Hamidreza Azizi and Erwin van Veen 25 Apr 2023 - 15:44

Welcome to the second edition of our blog ‘Iran in transition’ that tracks different dimensions of the evolution of protests and governance in Iran. In our last blog, we offered four indicators that help map out dynamics that can occur in a situation characterized by repressive governance and widespread social discontent: the quality of state-society relations, the nature of intra-elite dynamics, economic prospects and foreign affairs. In this blog, we examine Iran’s foreign relations with regard to the transitional state the country has entered into since the eruption of the 2022/2023 protests.

There is a paradox at the heart of Iran’s foreign relations. On the one hand, Tehran appears to feel more confident than ever due to its recent achievement of a number of foreign policy milestones. These include a strategic upgrade of its relationship with Russia, closer ties with China, a newly minted understanding with Saudi Arabia and the absence of consequences for keeping the nuclear negotiations in a dead end. Iran’s ruling elites might be forgiven for feeling they are gaining the upper hand in their geopolitical travails, at least for now. On the other hand, these headline successes obscure significant longer-term economic and geopolitical risks One is the difficulty of achieving economic growth equivalent to the volume that would be possible once US-imposed sanctions were lifted. Another risk are the ramifications of a possible Russian strategic defeat in Ukraine. A third risk is long-term strategic dependence on China as Tehran’s presumed economic savior from US sanctions. Finally, growing ties between the US, Israel, Azerbaijan and the UAE risk constraining Iran’s room for maneuver in its near abroad. But these risks do not seem to be perceived as overly serious in Tehran at the moment.

This situation arguably gives rise to a variation of the ‘Thucydides trap’, as coined by Graham Allison, in the sense that Iranian overconfidence in the strength of its present geopolitical position can lead to a more assertive foreign policy than its true strength warrants. In turn, this can trigger both greater fear and stronger counter-responses from countries like Israel and the United States than what might otherwise occur. We explore the listed factors in turn in order to assess their net geopolitical effect on Iran’s government.

The combination of Western sanctions and Russia’s poor military performance in Ukraine has made Moscow more dependent on Iran to the effect of upgrading Tehran to peer status rather than maintaining it as the junior partner it used to be. Iran has become a key arms supplier to Russia, which is most visible in the large volume of precise, low cost and long range Shahed 131/136 drones. Reports indicate that Iran might be also considering the delivery of ballistic missiles to Moscow. In addition, Russia and Iran are in the process of reviving the north-south corridor to facilitate their trade and connections with India and the Far East. Trade traffic appears to be picking up even though the real expansion of the north-south route remains on the drawing board. Russia now also needs Iran as conduit for industrial inputs it cannot produce itself, such as chips and dual use goods, but also engineering services. The multilateral element of Tehran-Moscow relations has similarly gained in importance over the past year, which is reflected in Iran’s full membership in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and its growing cooperation with the Russia-dominated Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU).

The routes are potential rather than actual. ©Clingendael

To this series of foreign policy achievements, one can add the start of implementation of the ‘Iran-China 25-Year Comprehensive Cooperation Agreement’ in January 2022 (signed in March 2021). Although its contents are shrouded in secrecy, estimates of Chinese investment in Iran in exchange for cheap oil deliverables and consumer good market dominance run into the billions of dollars. The agreement has the potential to bring Iran economic benefits of the same order of magnitude as Tehran’s booming relation with Russia generates in the political-security realm.

Then there is the recent rapprochement between Iran and Saudi Arabia. It reduces the latter’s incentives to join Israeli-US military activity against Tehran and holds out the possibility of realizing a Saudi exit from the Yemen quagmire that Mohammed bin Salman has created for himself at great cost to Saudi Arabia’s international reputation and its Treasury. The recent extension of the cease fire in Yemen until the end of 2023 is indicative that this path might be trodden. While suggestions of large-scale Saudi investment in Iran seem unlikely as long as the US/EU sanctions regime is in force and Iran’s banking sector remains high-risk, Riyadh could start by modest investments in non-sanctioned industries, purchase Iranian oil under the radar and resell it as a service to Tehran, or simply facilitate its export. Yet, even though the ‘deal’ is best seen as a small step in a difficult and far longer confidence-building trajectory, it nevertheless set a different tone in the relationship. It can also open the door for Iran to improve its relations with other Arab states, like Bahrain and Egypt.

Finally, irrespective as to whether some form of a revised or truncated nuclear deal is concluded, Iran does not currently feel much pressure of keeping the negotiations in limbo. In other words, Tehran does not perceive a need to make concessions – especially if the political and economic promises of deeper relations with Russia and China will show more tangible benefits in the near future. Despite growing war talk in some quarters, Iran is well aware that Israel cannot mobilize an adequate assault without US help and that even the US has no credible plan beyond a full scale war that requires weeks of prior deployment to amass the force necessary just to take out Iran’s air defenses. This would inevitably result in a regional conflict and likely accelerate Iran’s pursuit of nuclear weapons. In turn, it would distract Washington from Russia and China as strategic priorities. Otherwise put, it is more convenient to (pretend to) keep talking.

On balance, Iran’s ruling elites are likely to perceive that their alliances have become stronger while threats against them have diminished. The country’s longstanding revolutionary slogan “neither East nor West” encapsulated its desire to conduct an autonomous foreign policy. Within the confines of this slogan, Iran’s more conservative and hardline ruling elites have traditionally been more inclined to ‘look east’ in the tradition of Jalal Al-e-Ahmad’s 1962 treatise on ‘Westoxification’. Now that these elites fully dominate the Islamic Republic of Iran - after the Guardian Council excluded reformist and moderate elites from running during the 2021 presidential and parliamentary elections – they are trading the old slogan for a new ‘look east’ policy. Yet, the payoff they expect from this policy shift overlooks major risks.

One such risk is that the economic benefits of deeper relations with Russia and China will be hard to realize. In the case of Russia, this is because the Iranian and Russian economies are structurally fairly similar, which constrains the achievable volume and limits mutual benefits. Moreover, turning the north-south corridor into a trade highway requires billions in hard infrastructure investment, agreement on a range of soft infrastructure measures between the countries involved (like non-tariff barriers to trade), a coherent national infrastructure plan and years of works and upgrades. This is not impossible, but it will take time that will defer benefits to the medium-term.

In the case of China, it is hard to see investment in the order of hundreds of billions materialize as long as US sanctions remain in place. Investing such sums requires involvement from large, state-linked Chinese enterprises that typically also do business in Western countries and hence risk running afoul of the sanction regime (given Moscow’s own sanction predicament, Iranian trade and investment with Russia would remain sanction-depressed even if those on Iran were lifted). The economic depth that Iran-China relations can achieve thus depends on the extent of Beijing’s willingness to violate US sanctions at a greater scale. Such appetite is likely to be limited. Iran’s recent deal with Saudi Arabia will face the same cost/benefit calculus.

Another risk to Tehran is a Russian strategic defeat in Ukraine. Should Moscow not manage to make progress in the current war of attrition but suffer further reversals instead, the prospect of a domestic backlash, or even political change, in Russia cannot be excluded. Such a turn of events would jeopardize many of the benefits of the upgraded Iranian-Russian relationship. Russia already has had to face significant blows to its reputation for military prowess, the combat readiness of its armed forces and the state of its economy, even though the latter have been more gradual and manageable than many had assumed. But if the US and EU Member States remain steadfast in their support for Ukraine, strategic defeat is a possibility. In this regard, the endurance of EU policy cohesion and the US 2024 elections are critical over-the-horizon indicators. Either way, Iran appears to have underestimated the relevance of the war in Ukraine to the EU with the effect that the possibility of a rapprochement between Tehran and Brussels will remain off the table for quite some time to come, irrespective of the course of the war on the battlefield.

Selected foreign relations of Iran and Israel.

A final risk consists of deepening ties between the US and Israel on the one hand, and the KDP-led part of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, Azerbaijan, Bahrain and the UAE on the other hand. The intelligence on Iran that can be gleaned from such ties might not just enable sabotage operations within Iran but, more dangerously, be used to counter sanction evasion. Greater sanction enforcement is, after all, a low-cost method for the US to contain Iran and encourage domestic unrest. At the very least, closer ties could discourage future trade with, and investment in, Iran by the Arab countries of the Persian Gulf and the Levant. Zooming out, one can also view Iran as being increasingly subject to Israeli strategic encirclement, replicating Tehran’s own longstanding policy towards Tel Aviv via the likes of Hezbollah and Hamas. Iran’s efforts to improve relations with its Arab neighbors are unlikely to convince these states to sever their growing ties with Israel since they simply seek to hedge their positions. In other words, Israel will exercise long-term influence on Iran’s direct security environment, which is likely to give the Islamic Republic a persistent security headache.

Yet, none of these risks seem to be perceived as overly serious in Tehran at the moment. As a result, its foreign policy establishment – the Supreme Leader, his office and the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps – appear to be in a buoyant mood. Linking this back to domestic unrest and protests, such sentiment is unlikely to tempt Iran’s ruling elites into making any concessions to those on the streets, or to feel pressure in having to make concessions in the nuclear deal negotiations due to domestic protests. In its thinking as sketched out above, Tehran rather expects a substantial economic payoff in the short-term from the deepening of its north- and eastbound relations. At best, a sense of foreign policy success might make Iran’s ruling elites sufficiently confident to be more permissive of future protests and dissent.