In India’s 85-year-long Test history, only four of the 289 male Test cricketers have reportedly been Dalits. While concrete steps have been taken to address a similar under-representation of non-white players in South Africa, Dalit under-representation in Indian cricket has received scant attention. There is a need to understand this as a function of systemic barriers arising from corporate patronage post-independence and the urban stranglehold of the game, instead of attributing it to choice, inherent inability or upper caste “tastes.” The grass-roots development approach of Cricket South Africa can serve as an example to address this anomaly.

The authors are grateful to their colleagues Shreedhar Kale and Hrishika Jain for their feedback on this paper.

Over the past two seasons, talent drain in South African cricket has been dominating the headlines of cricket tabloids (Moonda 2017a). This drain occurred due to two coincidental, but unrelated phenomena. The first of these is that Cricket South Africa (CSA) began imposing “transformation targets,” that is, racial quotas, due to pressure from the South African Department of Sports and Recreation. While this was long believed to be the unsaid policy of the board (Moonda 2015),1 it has now been formalised across playing levels. These transformation targets mandate that on an average, the national playing 11 must include six players of colour, of which two must be black. The targets are slightly higher at the lower levels of the game. The second factor was announcement of Britain’s exit from the European Union (Brexit), which has left a limited window for Kolpak entries to the county game.2 This limited window due to Brexit tempted those who were uncertain of a stable future in international cricket to opt for the Kolpak route due to higher salaries in the county game in England (Holme 2017).

Apart from being a factor in the departure of promising players such as Kyle Abbott, Riley Russouw and David Wiese from the international game, the quota system also came under the scanner for preventing CSA from bidding to host any major international event. A report by an eminent persons group (EPG) commissioned by the sports ministry found that CSA, among other sporting bodies, had failed to meet its transformation targets. Consequently, the ministry barred all the errant sporting bodies, including CSA, from bidding to host any international events such as the World Cup and Champions Trophy (Moonda 2016). That the ban was effective in incentivising CSA to meet its targets is evident from the fact that CSA exceeded transformation targets in less than a year, resulting in the ban being lifted (Moonda 2017b). However, the transformation quota system comes under the scanner every time the national team underperforms. For instance, after the South African team lost to England by a large margin, former South African cricketer, Graeme Pollock argued that the quotas resulted in poor selections and were also weakening the domestic circuit (SA Cricket 2017).

https://www.epw.in/journal/2018/21/special-articles/does-india-need-caste-based-quota-cricket.html

---------------------------------

In his book, Ramachandra Guha has argued that “From the 1950s through the 1980s, the South Indian and Bombay Brahmins dominated the scene. Besides, the Brahmins were also powerful in the administration of the game.”

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09523369708713971?cookieSet=1

-------------

Cricket in India was once considered to be the game of the English sahibs, kings, nawabs and affluent people. After Independence, the idea of royalty waned and with that, their presence in the national team. First transition in the team selection came when other power elites entered the arena and displaced the royalty. This new breed was mostly coming from big cities, from affluent upper caste families and last but not the least, from a class that had access to Gymkhanas and other clubs—places where their capabilities could be noticed.

I am proposing that Indian cricket is going through another big transition, especially in the IPL and club cricket era.

IPL has led to huge massification of the game. During last year’s season, the Mumbai Indians vs Chennai Super Kings match had peak viewership of 8.3 million on the OTT platform. TV viewership for IPL fixtures sometimes touches 200 million. All this has changed the game itself. Subalterniastion of cricket is the most important by-product of IPL.

The last T20I match India played against Sri Lanka this season has players like Yadav, Patel, Gill, Hooda, Mavi, Chahal, Malik — all coming from non-descript families and lacking any sort of so-called blue blood’. Even their leader, Pandya, comes from a humble background.

After Independence, the domination of the kings and princes reduced. It’s not easy to explain how the urban elites, especially the Brahmins, started to dominate the game during that transition. Author S. Anand, in his article has compiled data of the Indian Test team and come to the conclusion that “through the 1960s till the 1990s, Test-playing Indian teams averaged at least six Brahmins, sometimes even nine.” In his book, Ramachandra Guha has argued that “From the 1950s through the 1980s, the South Indian and Bombay Brahmins dominated the scene. Besides, the Brahmins were also powerful in the administration of the game.”

Another interesting data set has been provided by Shubham Jain and Gaurav Bhawnani, graduates of National Law School of India University, Bangalore. For their 2018 research paper, they pulled data from the archives to demonstrate that “in India’s 85-year-long Test history, only four of the 289 male Test cricketers have reportedly been Dalits.” The paper also listed the big city domination: “In 1970s-80s, about half of the Indian Test cricket team hailed from merely six cities: Mumbai, Chennai, Delhi, Bangalore, Hyderabad and Kolkata.” The authors have mentioned a similar phenomenon in South African cricket of that era and the diversity project there. (You may read the shorter version of the paper here.)

Underrepresentation of players from lower and middle caste origins in Indian cricket team before 1990s is a fact empirically proved and documented by many authors such as Richard Cashman, Ashis Nandy, Andrew Stevenson, Kieran Lobo, Ramachandra Guha, Suresh Menon, Amrit Dhillon, Arvind Swaminathan among others.

Much scholarly work is available on the lack of diversity in Indian cricket, so I would not venture into that territory. Rather, I would argue that the scenario is changing and the earlier papers and articles are now more of an archival value.

There are three probable reasons for this transition:

https://theprint.in/opinion/indian-...hahal-patel-hooda-leading-the-change/1304067/

---

Lot of Brahmans on social media are claiming that 3 Yadavs should not be allowed to play on team, Surya Kumar Yadav, Kuldeep Yadav and Umesh Yadav.

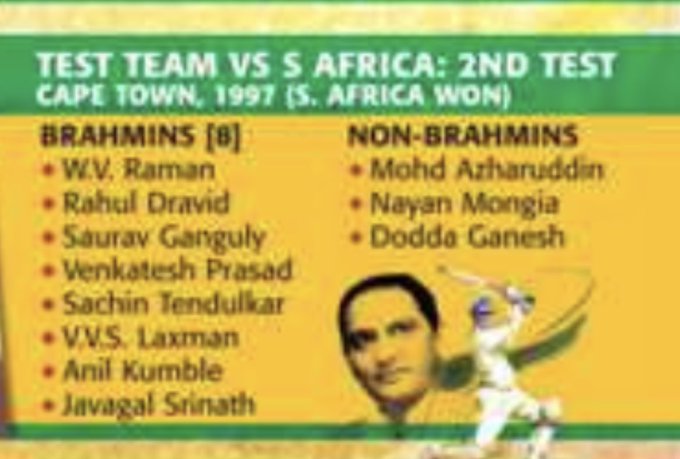

1997 India Vs South Africa, Cape Town test match - 8 Brahmans in single team, and India lost the match.

1. Change in format:Test cricket once used to be the most popular and only international format of the game. As it is largely a relaxed game, the cricketers need not be very athletic and robust …especially the batsmen who could excel and produce high scores majorly relying on their technique and pursuance of personal records. One-day format changed the rules and physical fitness and agility became important factors in team selection.

This was further stretched by the T20 format. As saving runs became very critical, good fielders with physical fitness have a better chance at being selected. Cricket has become competitive and result oriented. With this, the discretion of the selection committee has reduced.

It’s now not easy to continue being a non-performer for long. Even the most celebrated player would be dropped irrespective of reputation, if he fails to perform continuously in half-a-dozen matches. This has opened opportunities for other players.

2. Massification of the game: Cricket hasc eased to be a game of the elites. Test cricket has made way for ODI and T20s, adding immense amount of excitement and drama. This has made the game massively popular among the ordinary masses. Crores of people watch cricket…and when they find a player not performing, they vent their anger out on social media. If they see a player not finding a place in the national team despite performing well in the IPL, they ensure BCCI knows this. Recently, we have seen such outrage in support of SanjuSamson

3. Regional reach:IPL has increased competitiveness and because the league has taken the game to smaller towns, franchises who have their teams in such pockets look for better performing players from all parts of the country.

http://raviwar.com/baatcheet/b25_interview-prabhash-joshi-alok-putul.shtml

The authors are grateful to their colleagues Shreedhar Kale and Hrishika Jain for their feedback on this paper.

Over the past two seasons, talent drain in South African cricket has been dominating the headlines of cricket tabloids (Moonda 2017a). This drain occurred due to two coincidental, but unrelated phenomena. The first of these is that Cricket South Africa (CSA) began imposing “transformation targets,” that is, racial quotas, due to pressure from the South African Department of Sports and Recreation. While this was long believed to be the unsaid policy of the board (Moonda 2015),1 it has now been formalised across playing levels. These transformation targets mandate that on an average, the national playing 11 must include six players of colour, of which two must be black. The targets are slightly higher at the lower levels of the game. The second factor was announcement of Britain’s exit from the European Union (Brexit), which has left a limited window for Kolpak entries to the county game.2 This limited window due to Brexit tempted those who were uncertain of a stable future in international cricket to opt for the Kolpak route due to higher salaries in the county game in England (Holme 2017).

Apart from being a factor in the departure of promising players such as Kyle Abbott, Riley Russouw and David Wiese from the international game, the quota system also came under the scanner for preventing CSA from bidding to host any major international event. A report by an eminent persons group (EPG) commissioned by the sports ministry found that CSA, among other sporting bodies, had failed to meet its transformation targets. Consequently, the ministry barred all the errant sporting bodies, including CSA, from bidding to host any international events such as the World Cup and Champions Trophy (Moonda 2016). That the ban was effective in incentivising CSA to meet its targets is evident from the fact that CSA exceeded transformation targets in less than a year, resulting in the ban being lifted (Moonda 2017b). However, the transformation quota system comes under the scanner every time the national team underperforms. For instance, after the South African team lost to England by a large margin, former South African cricketer, Graeme Pollock argued that the quotas resulted in poor selections and were also weakening the domestic circuit (SA Cricket 2017).

https://www.epw.in/journal/2018/21/special-articles/does-india-need-caste-based-quota-cricket.html

---------------------------------

In his book, Ramachandra Guha has argued that “From the 1950s through the 1980s, the South Indian and Bombay Brahmins dominated the scene. Besides, the Brahmins were also powerful in the administration of the game.”

Cricket, caste, community, colonialism: the politics of a great game

Ramachandra Guhahttps://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09523369708713971?cookieSet=1

-------------

Indian cricket seeing tectonic shift—Yadavs, Mavi, Chahal, Patel, Hooda leading the change

India is seeing more and more cricketers from farming and cattle-rearing communities like Jats, Patidars, Ahirs, Gurjars and other OBC communities.

Cricket in India was once considered to be the game of the English sahibs, kings, nawabs and affluent people. After Independence, the idea of royalty waned and with that, their presence in the national team. First transition in the team selection came when other power elites entered the arena and displaced the royalty. This new breed was mostly coming from big cities, from affluent upper caste families and last but not the least, from a class that had access to Gymkhanas and other clubs—places where their capabilities could be noticed.

I am proposing that Indian cricket is going through another big transition, especially in the IPL and club cricket era.

IPL has led to huge massification of the game. During last year’s season, the Mumbai Indians vs Chennai Super Kings match had peak viewership of 8.3 million on the OTT platform. TV viewership for IPL fixtures sometimes touches 200 million. All this has changed the game itself. Subalterniastion of cricket is the most important by-product of IPL.

The last T20I match India played against Sri Lanka this season has players like Yadav, Patel, Gill, Hooda, Mavi, Chahal, Malik — all coming from non-descript families and lacking any sort of so-called blue blood’. Even their leader, Pandya, comes from a humble background.

The historical composition

This is indeed a welcome change that is making the game popular and richer. Earlier, we had a long list of cricketers from royal lineage — Nawab Mansoor Ali Khan Pataudi, K.S. Ranjitsinhji, Duleepsinhji, Maharajah of Vizianagram “Vizzy”, Maharaja of Porbandar Natwarsinhji, Maharaja of Patiala Bhupinder Singh, Hanumant Singh of Banswara State, Yajurvindra Singh among others. Maharaja of Porbandar was made captain of the Indian team during the first tour of England in 1932 as “protocol demanded a royal-led the team.” (1, 2). In those days, the selectors had limited leeway in the selection process and the competitiveness too was not that sharp. The game was leisurely, with Test being the main format.After Independence, the domination of the kings and princes reduced. It’s not easy to explain how the urban elites, especially the Brahmins, started to dominate the game during that transition. Author S. Anand, in his article has compiled data of the Indian Test team and come to the conclusion that “through the 1960s till the 1990s, Test-playing Indian teams averaged at least six Brahmins, sometimes even nine.” In his book, Ramachandra Guha has argued that “From the 1950s through the 1980s, the South Indian and Bombay Brahmins dominated the scene. Besides, the Brahmins were also powerful in the administration of the game.”

Another interesting data set has been provided by Shubham Jain and Gaurav Bhawnani, graduates of National Law School of India University, Bangalore. For their 2018 research paper, they pulled data from the archives to demonstrate that “in India’s 85-year-long Test history, only four of the 289 male Test cricketers have reportedly been Dalits.” The paper also listed the big city domination: “In 1970s-80s, about half of the Indian Test cricket team hailed from merely six cities: Mumbai, Chennai, Delhi, Bangalore, Hyderabad and Kolkata.” The authors have mentioned a similar phenomenon in South African cricket of that era and the diversity project there. (You may read the shorter version of the paper here.)

Underrepresentation of players from lower and middle caste origins in Indian cricket team before 1990s is a fact empirically proved and documented by many authors such as Richard Cashman, Ashis Nandy, Andrew Stevenson, Kieran Lobo, Ramachandra Guha, Suresh Menon, Amrit Dhillon, Arvind Swaminathan among others.

Much scholarly work is available on the lack of diversity in Indian cricket, so I would not venture into that territory. Rather, I would argue that the scenario is changing and the earlier papers and articles are now more of an archival value.

A new shift

Now we see more and more cricketers from farming and cattle-rearing communities like Jats, Patidars, Ahirs, Gurjars and other OBC communities. Journalist Sagar Choudhary hails this phenomenon as “silent revolution of lower castes” in Indian cricket. Interestingly, this phenomenon of diversity and democratisation of Indian cricket has not yet reached the lowest rung of the caste hierarchy and social order that is the SCs and the STs. Despite missing SC and ST players in the national team, the change is visible. Domination of Mumbai, Chennai and Delhi is also receding. More and more players are coming from small towns.There are three probable reasons for this transition:

- Change in format:Test cricket once used to be the most popular and only international format of the game. As it is largely a relaxed game, the cricketers need not be very athletic and robust, especially the batsmen who could excel and produce high scores majorly relying on their technique and pursuance of personal records. One-day format changed the rules and physical fitness and agility became important factors in team selection. This was further stretched by the T20 format. As saving runs became very critical, good fielders with physical fitness have a better chance at being selected. Cricket has become more competitive and result oriented. With this, the discretion of the selection committee has reduced. It’s now not easy to continue being a non-performer for long. Even the most celebrated player would be dropped irrespective of reputation, if he fails to perform continuously in half-a-dozen matches. This has opened opportunities for other players.

- Massification of the game: Cricket hasceased to be a game of the elites. Test cricket has made way for ODI and T20s, adding immense amount of excitement and drama. This has made the game massively popular among the ordinary masses. Crores of people watch cricket and when they find a player not performing, they vent their anger out on social media. If they see a player not finding a place in the national team despite performing well in the IPL, they ensure BCCI knows this. Recently, we have seen such outrage in support of Sanju Samson.

- Regional reach:IPL has increased competitiveness and because the league has taken the game to smaller towns, franchises who have their teams in such pockets look for better performing players from all parts of the country. This has enhanced the catchment area of the game. More and more players in the national team are coming from regions hitherto unrepresented.

https://theprint.in/opinion/indian-...hahal-patel-hooda-leading-the-change/1304067/

---

Lot of Brahmans on social media are claiming that 3 Yadavs should not be allowed to play on team, Surya Kumar Yadav, Kuldeep Yadav and Umesh Yadav.

1997 India Vs South Africa, Cape Town test match - 8 Brahmans in single team, and India lost the match.

1. Change in format:Test cricket once used to be the most popular and only international format of the game. As it is largely a relaxed game, the cricketers need not be very athletic and robust …especially the batsmen who could excel and produce high scores majorly relying on their technique and pursuance of personal records. One-day format changed the rules and physical fitness and agility became important factors in team selection.

This was further stretched by the T20 format. As saving runs became very critical, good fielders with physical fitness have a better chance at being selected. Cricket has become competitive and result oriented. With this, the discretion of the selection committee has reduced.

It’s now not easy to continue being a non-performer for long. Even the most celebrated player would be dropped irrespective of reputation, if he fails to perform continuously in half-a-dozen matches. This has opened opportunities for other players.

2. Massification of the game: Cricket hasc eased to be a game of the elites. Test cricket has made way for ODI and T20s, adding immense amount of excitement and drama. This has made the game massively popular among the ordinary masses. Crores of people watch cricket…and when they find a player not performing, they vent their anger out on social media. If they see a player not finding a place in the national team despite performing well in the IPL, they ensure BCCI knows this. Recently, we have seen such outrage in support of SanjuSamson

3. Regional reach:IPL has increased competitiveness and because the league has taken the game to smaller towns, franchises who have their teams in such pockets look for better performing players from all parts of the country.

http://raviwar.com/baatcheet/b25_interview-prabhash-joshi-alok-putul.shtml