Maula Jatt

ELITE MEMBER

- Joined

- Jul 24, 2021

- Messages

- 10,673

- Reaction score

- 19

- Country

- Location

The Pakistani middle class is past its scepticism of electronic money. How did we get here, and what comes next?

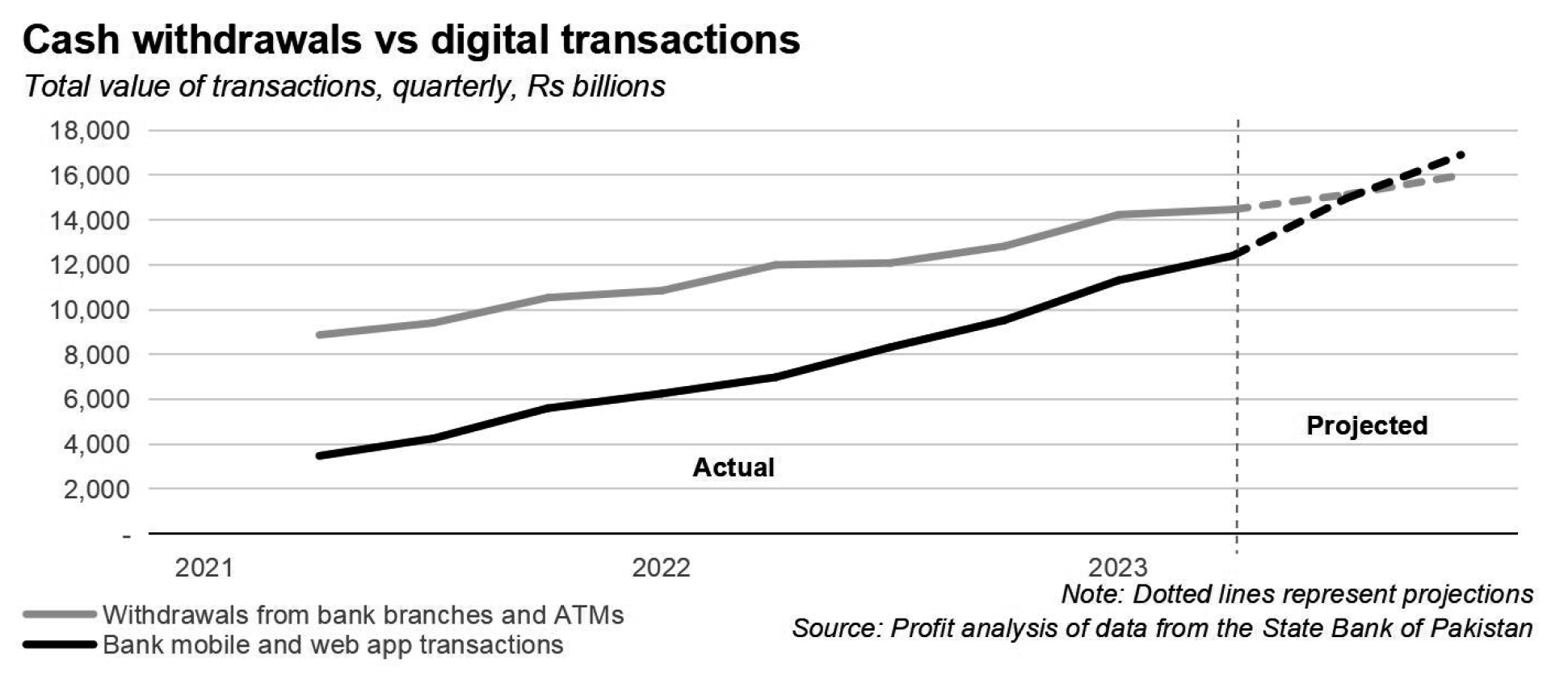

Some time over the next 12 months, Pakistan’s economy will cross an important milestone: the total volume of transactions that people conduct using their credit and debit cards, their bank apps, and web portals will exceed the total amount of cash they withdraw from bank branches or ATMs. In other words, to make a payment, if you are one of those Pakistanis who has a bank account, you will be more likely to use a card or the internet than go get cash from the closest bank branch or ATM.

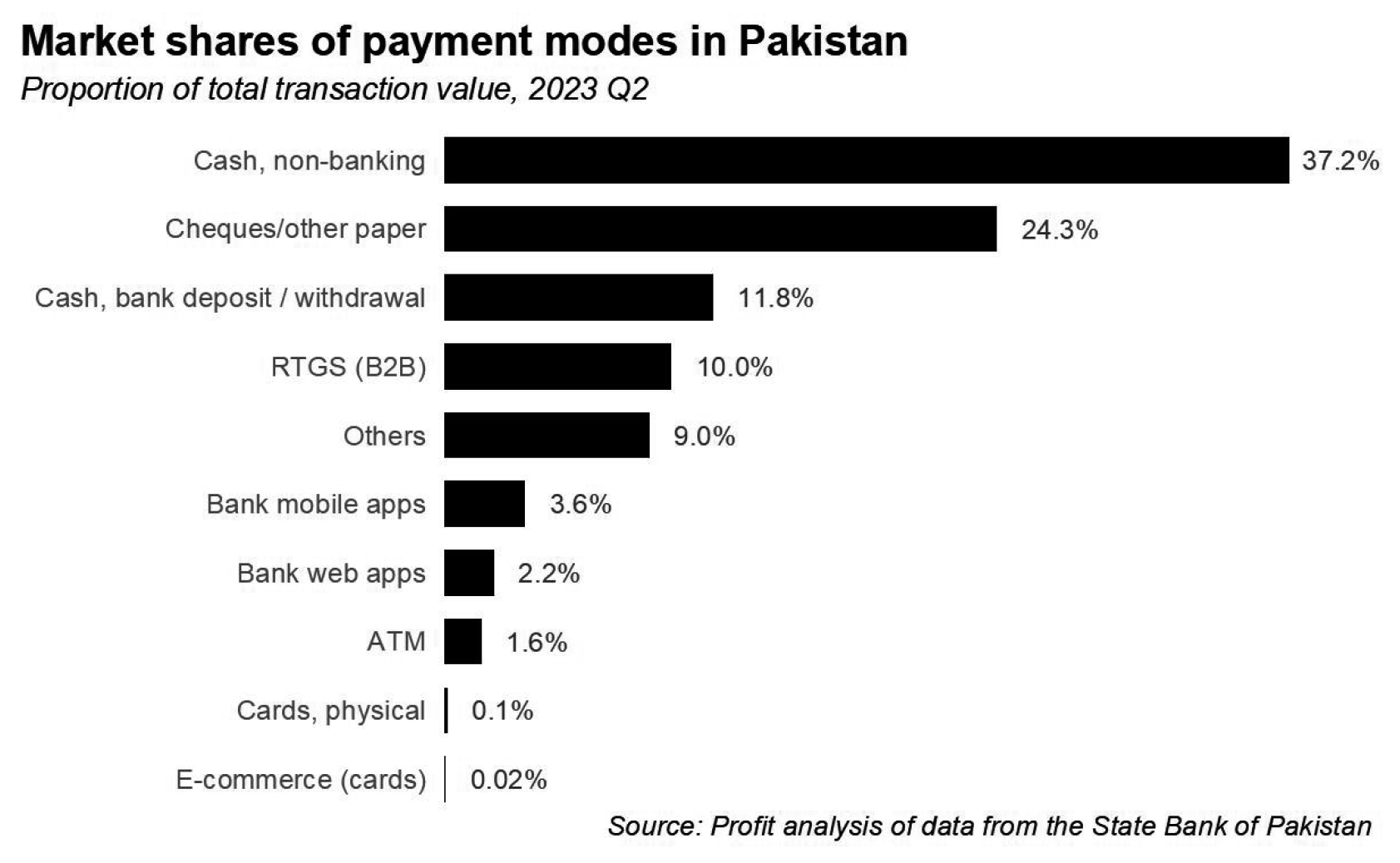

Cash is still very much king in Pakistan, accounting for about 37.2% of all transactions in the country (excluding interbank and government bond transactions) as of the second quarter of 2023, according to Profit’s analysis of data from the State Bank of Pakistan. But the myth that Pakistanis do not like transacting using electronic means needs to die. The evidence is in.

In fact, the question is not even whether and at what speed cash will go out of fashion. The most important question on this subject is how do business leaders take advantage of this shift that is already happening? Which payments companies or startups are poised to take advantage of this change? And given all of this, what effects can consumers expect to see in the scope of services that will be available to them?

It may be hard to see it now, given the incredibly difficult period that the Pakistani economy is still going through, but a tipping point has been reached and an exciting new stage of economic development is in the offing for Pakistan.

In this story, we will explore where we currently are with respect to the evolution of digital payments in Pakistan, how we got here, and what comes next.

Methodology of data analysis (feel free to skip)

A brief note on the data and methodology used in this article. The data comes from the State Bank of Pakistan’s quarterly and annual Payment Systems Review reports from the third quarter of calendar year 2016 through the second quarter of calendar year 2023. The reports extend much further back into the past as well, but the data appears to be compiled using a different methodology in prior years, and we included only data from the years where it seemed most directly comparable. Unless we specify otherwise, all growth rates mentioned in this article refer to the total value of transactions, not volume.

We also felt this was the most pertinent period to examine, since this is also the time when Pakistanis began to gain access to the internet in large numbers, following the auction of the 3G and 4G mobile broadband internet spectrum, which gave tens of millions of Pakistanis access to the internet for the first time.

Profit has not just compiled the data, but also combined it with other banking sector data to create as holistic a picture of payments in Pakistan as possible.

While the data for every other payment method is available in that report, what is not available is the volume of cash transactions that do not touch the banking system at either end (i.e. neither the giver nor the receiver of the cash is a banking or financial entity). While the volume of cash transactions is not directly measured by the State Bank of Pakistan, because it issues bank notes, it has a fairly good idea of exactly how much physical cash is in circulation at any given moment in time.

We made a simplifying assumption that the velocity of transactions involving physical cash is approximately the same as that involving the payments system in any given period. We are not certain as to how accurate this assumption is likely to be, but we also do not have a better number to go on.

Having calculated the total value of transactions involving cash, we then subtract from that the value of cash transactions involving the banks (ATM or branch withdrawals and deposits) to arrive at an estimate of the size of the cash-only transactions economy. This estimate is then plugged into any calculations involving market share of cash vs electronic payments.

One other note: we excluded interbank settlements and government bond transactions in our analysis, since those are transactions that are needed to keep the payments and banking system running. Counting them would likely end up double-counting many transactions and hence result in a skewed picture of what people are actually using to make their payments.

One final bit: we are putting in US dollar equivalents for many numbers in this story to help illustrate the scale of what we are talking about. Since almost all of the numbers involved represent flows over a period of time, we will adopt the convention of utilising the average exchange rate during that period, defined as the midpoint of the open market buying and selling exchange rates as published by Business Recorder.

The current state of play in payments

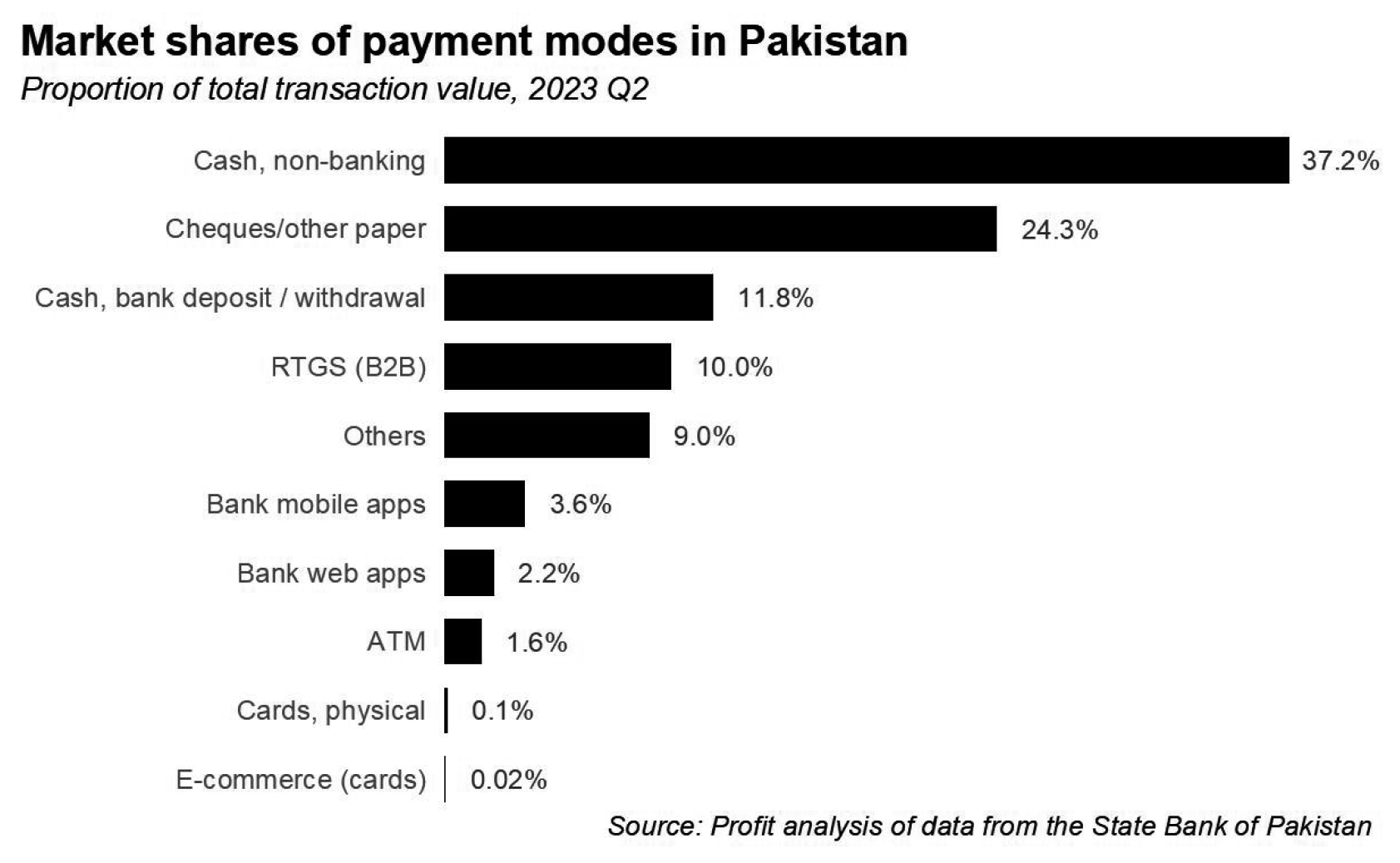

Take a look at where the current state of payments is in Pakistan, and you will notice the absolute dominance of cash. About 37.2% of transactions are cash-only – meaning they do not interact with the banking system on either the payer or receiver side. Another 11.8% are deposits and withdrawals from bank branches, and a further 1.6% are withdrawals and deposits at ATMs. All told, the total amount of transactions involving physical cash is about 50.7% of the value of all transactions in the country.

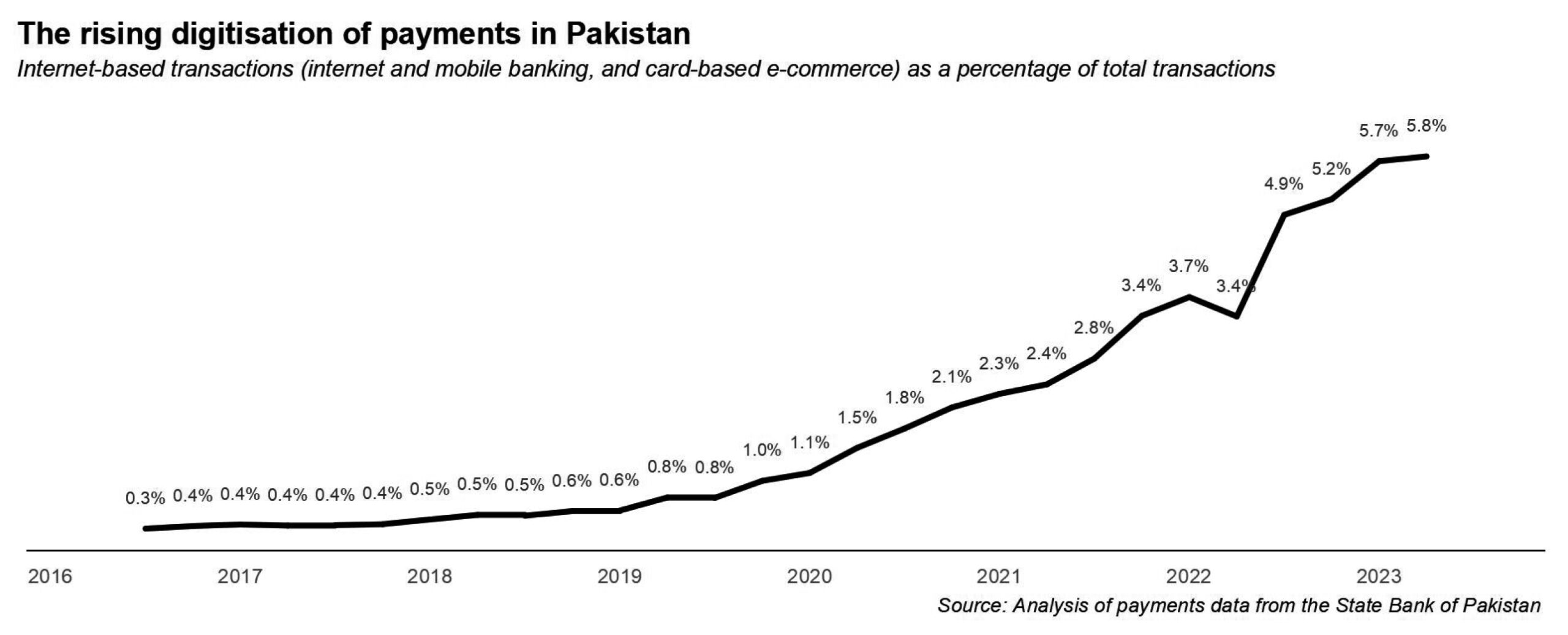

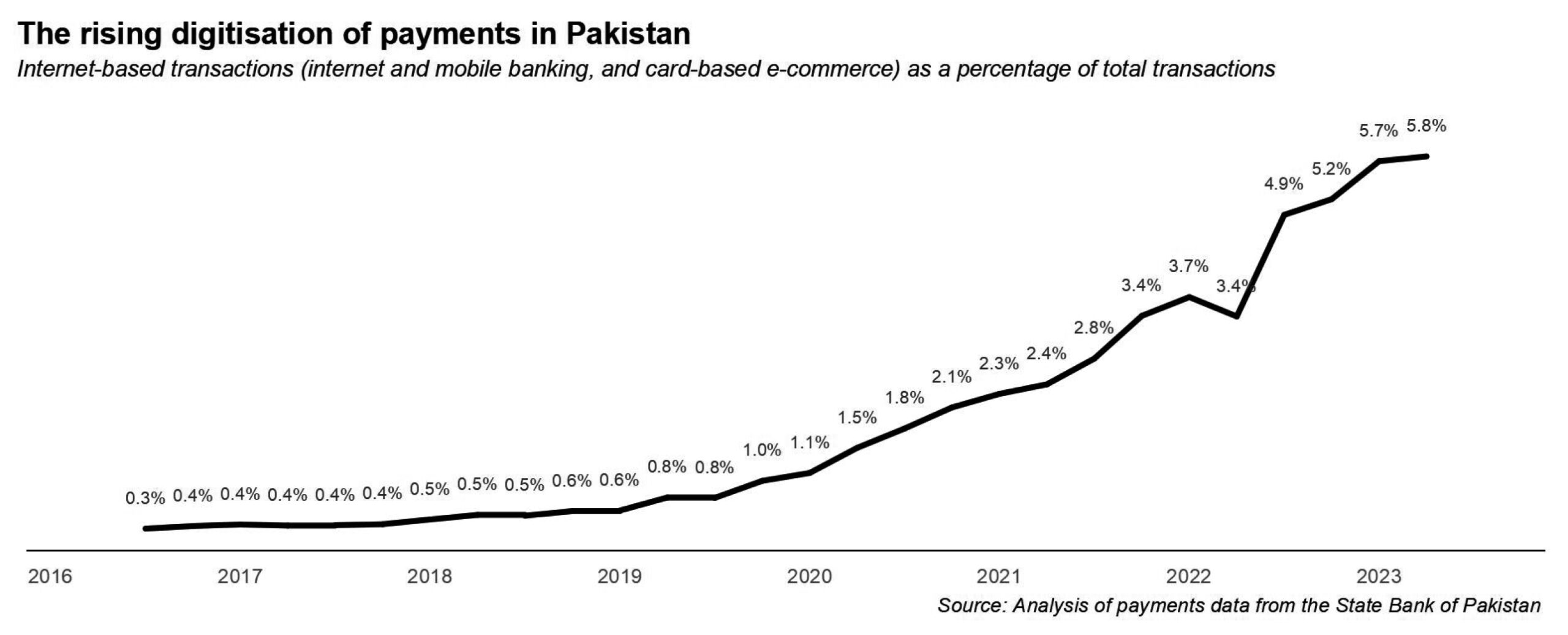

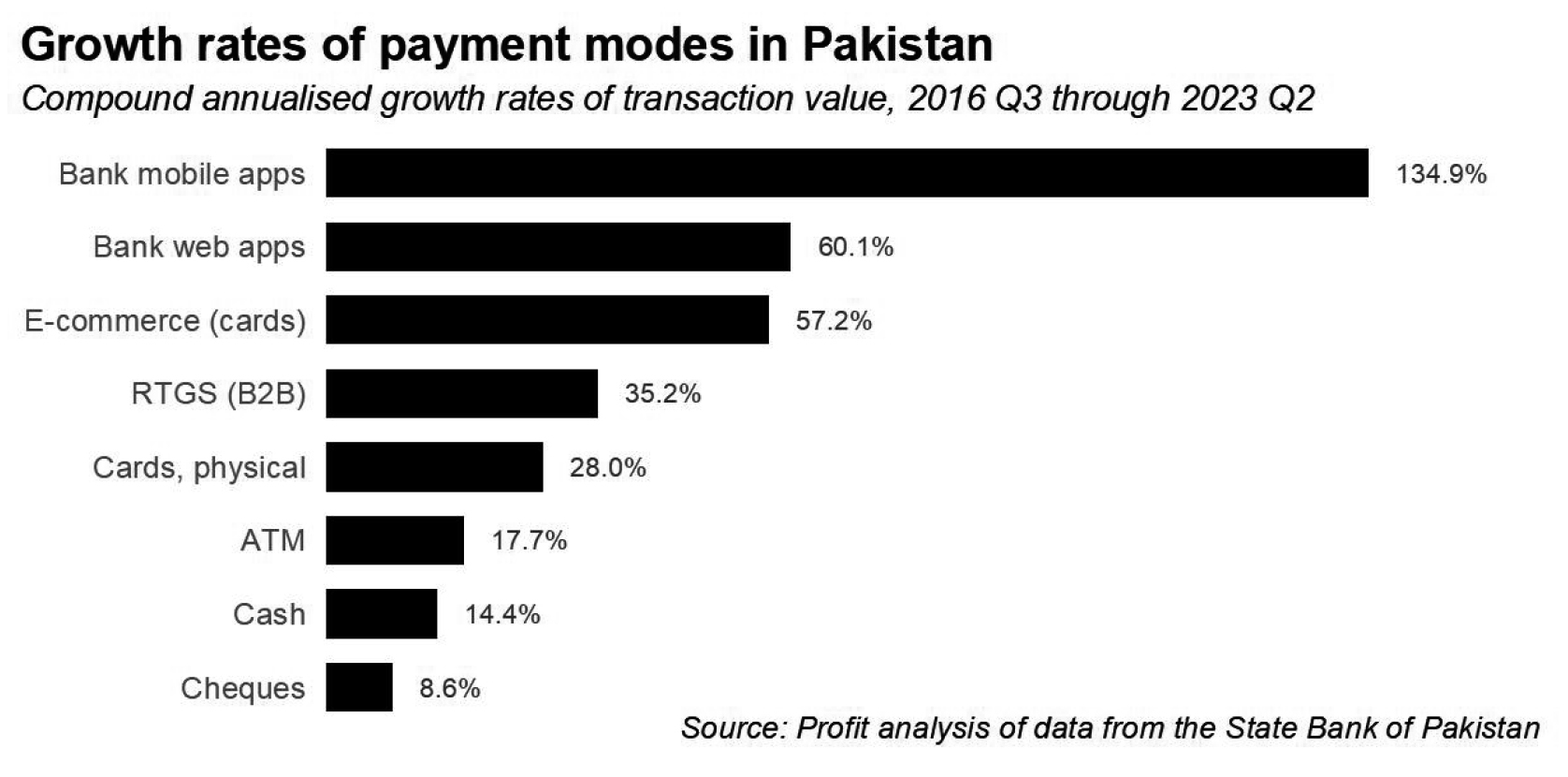

Indeed, purely electronic transactions account for just 15.9% of the value of all transactions in the country. (The bulk of the remainder is taken up by things like cheques, and other paper instruments.) But take a look at the growth rates and it becomes clear that growth in payments is coming largely from electronic payment methods, with cash and paper slowly but surely losing ground.

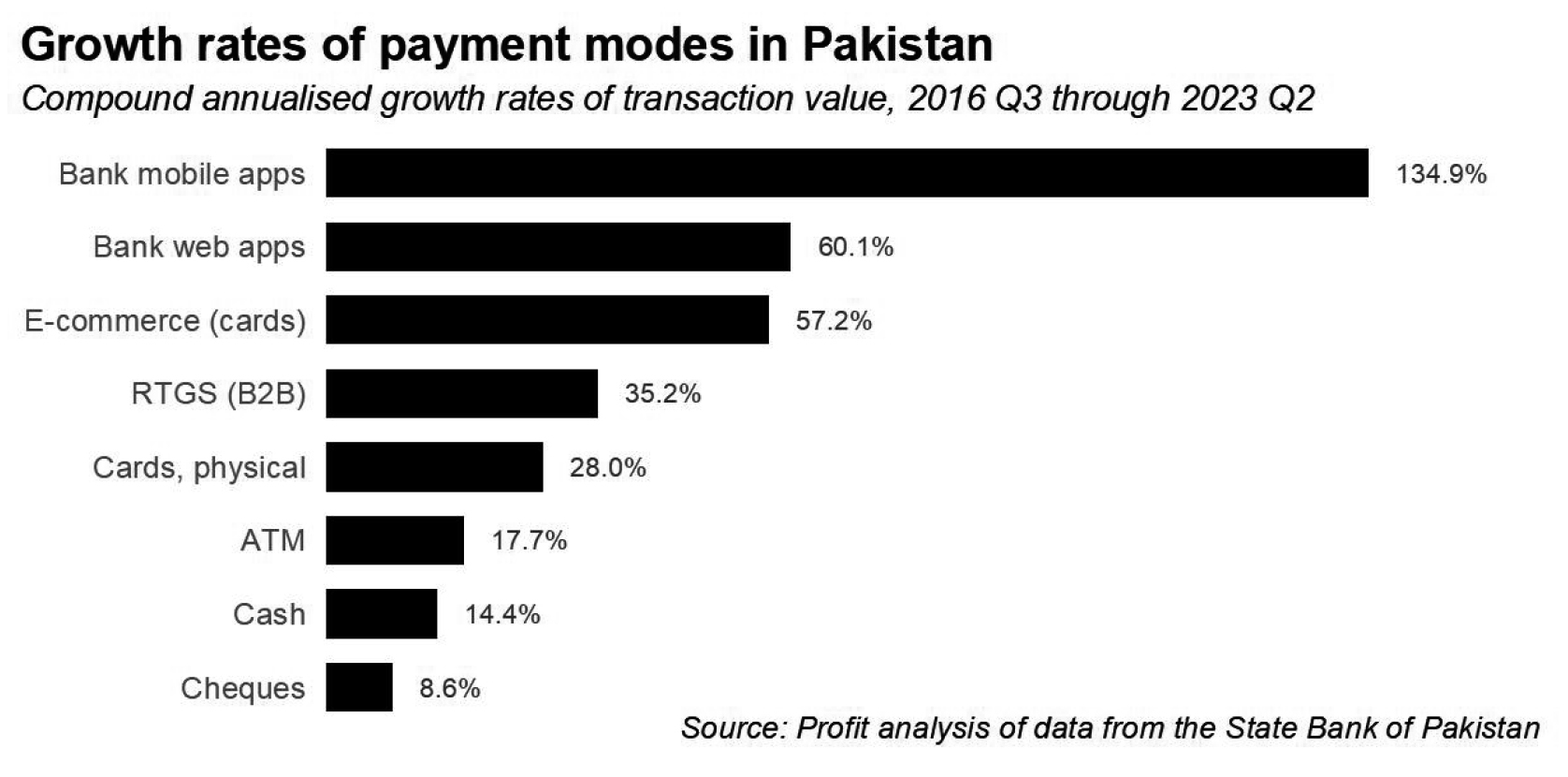

On the chart of the growth rates in payment value by payment type, all of the top five spots are taken up by internet-based methods.

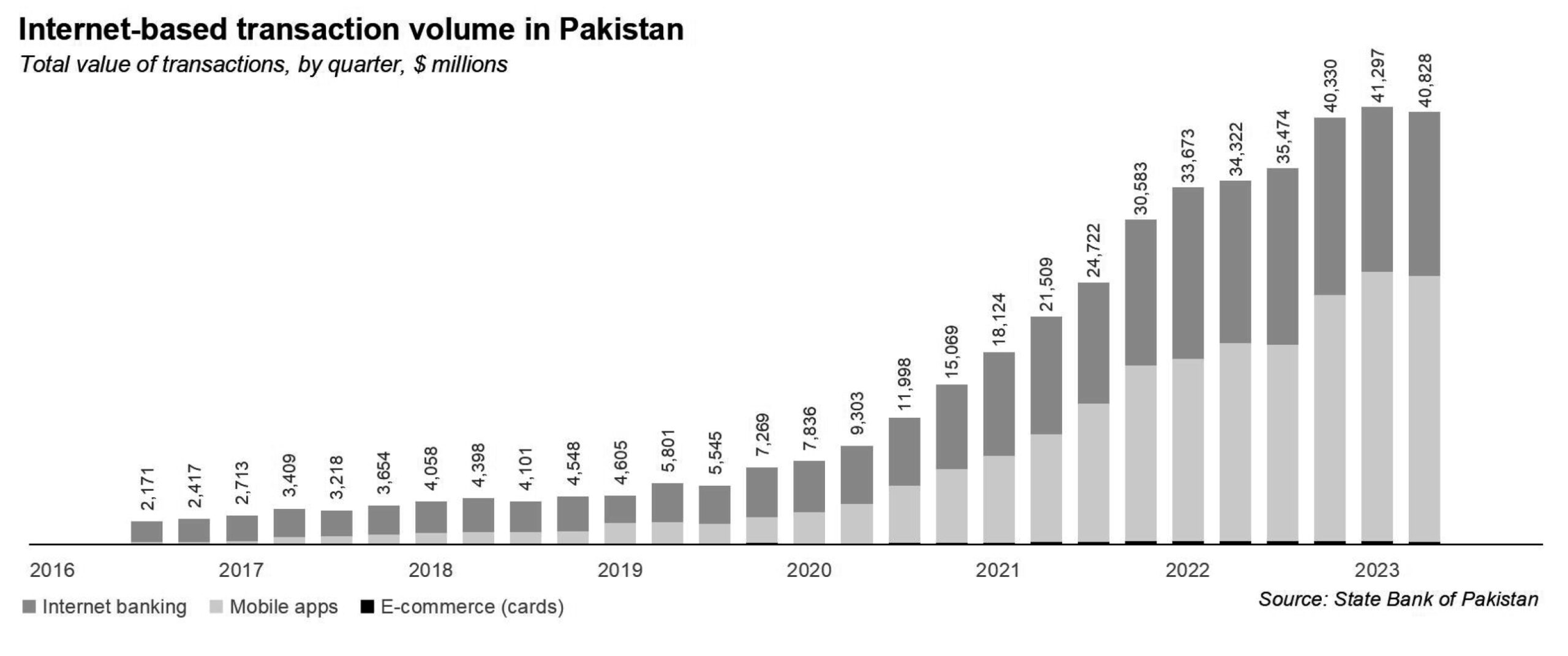

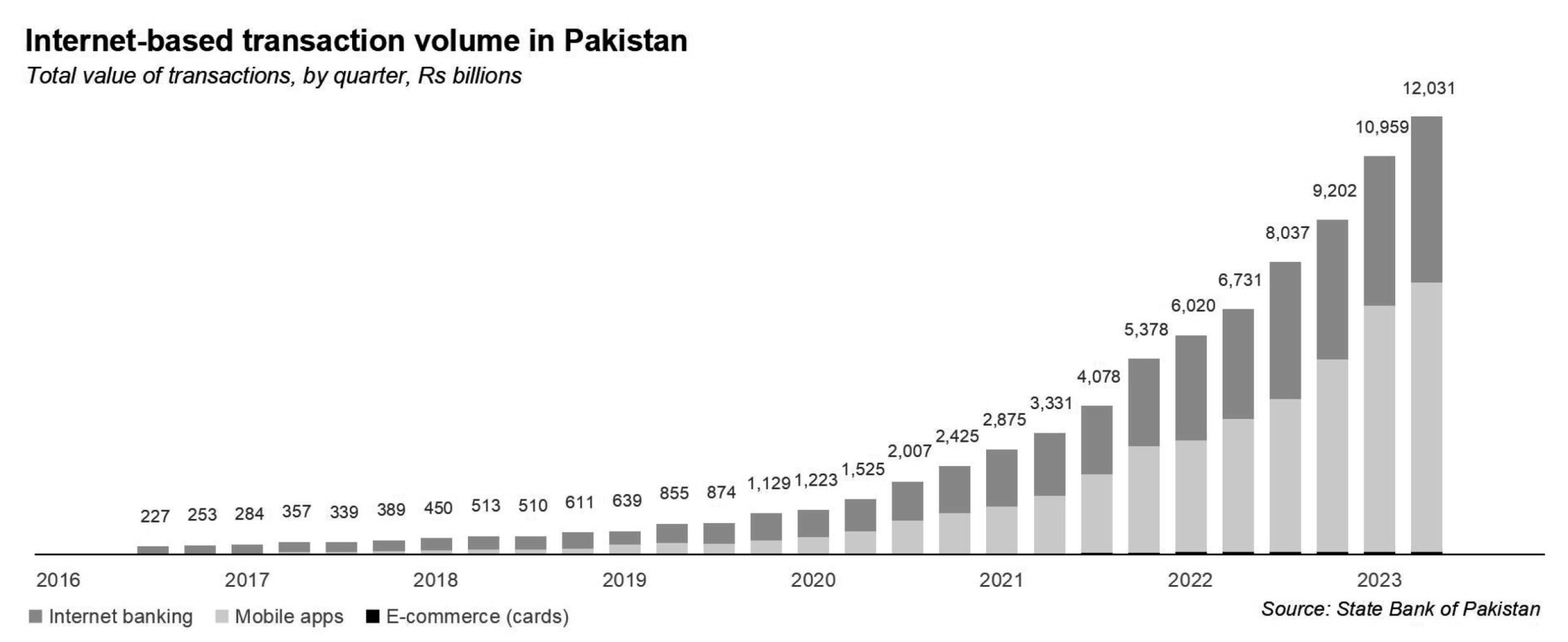

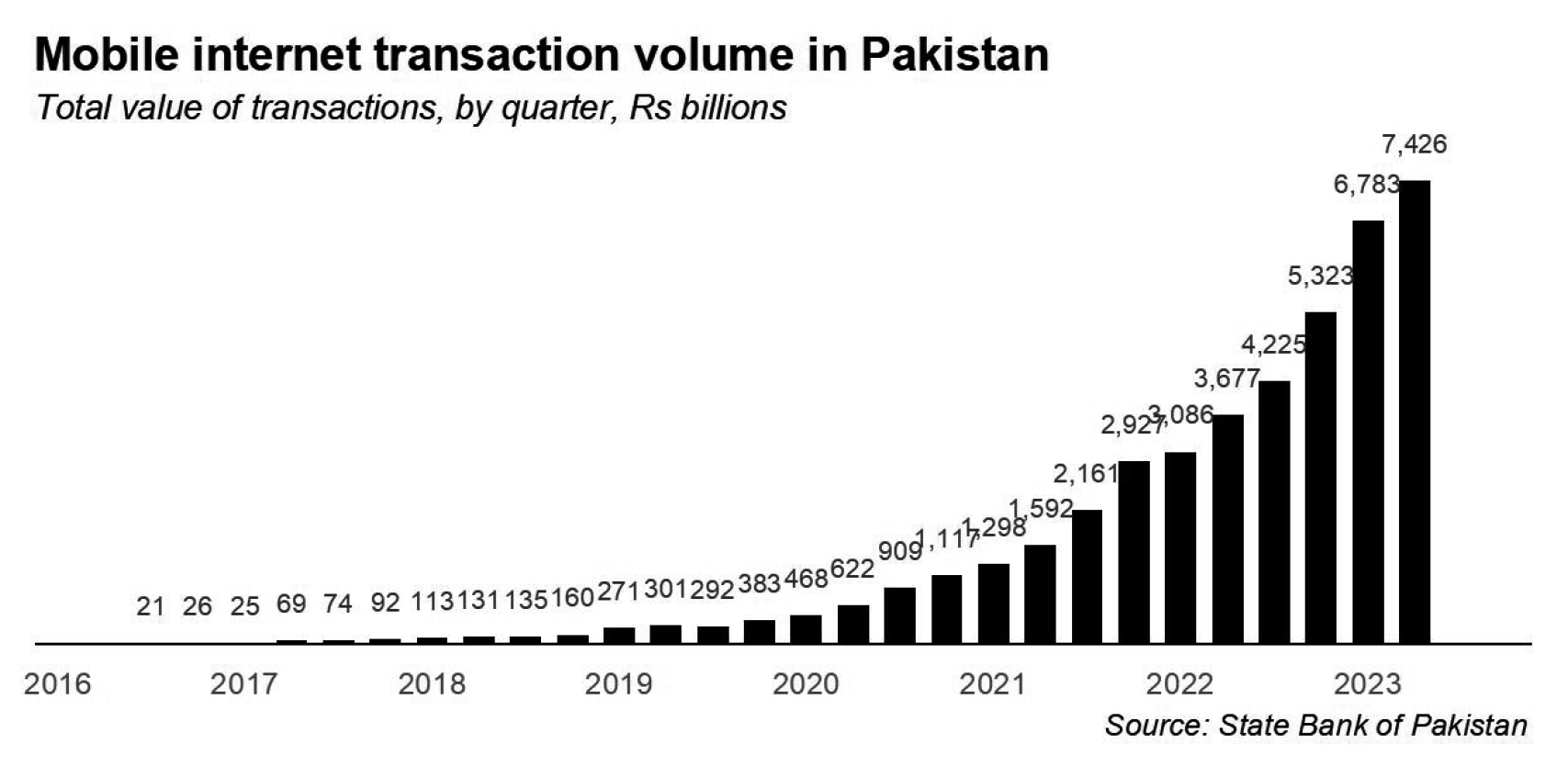

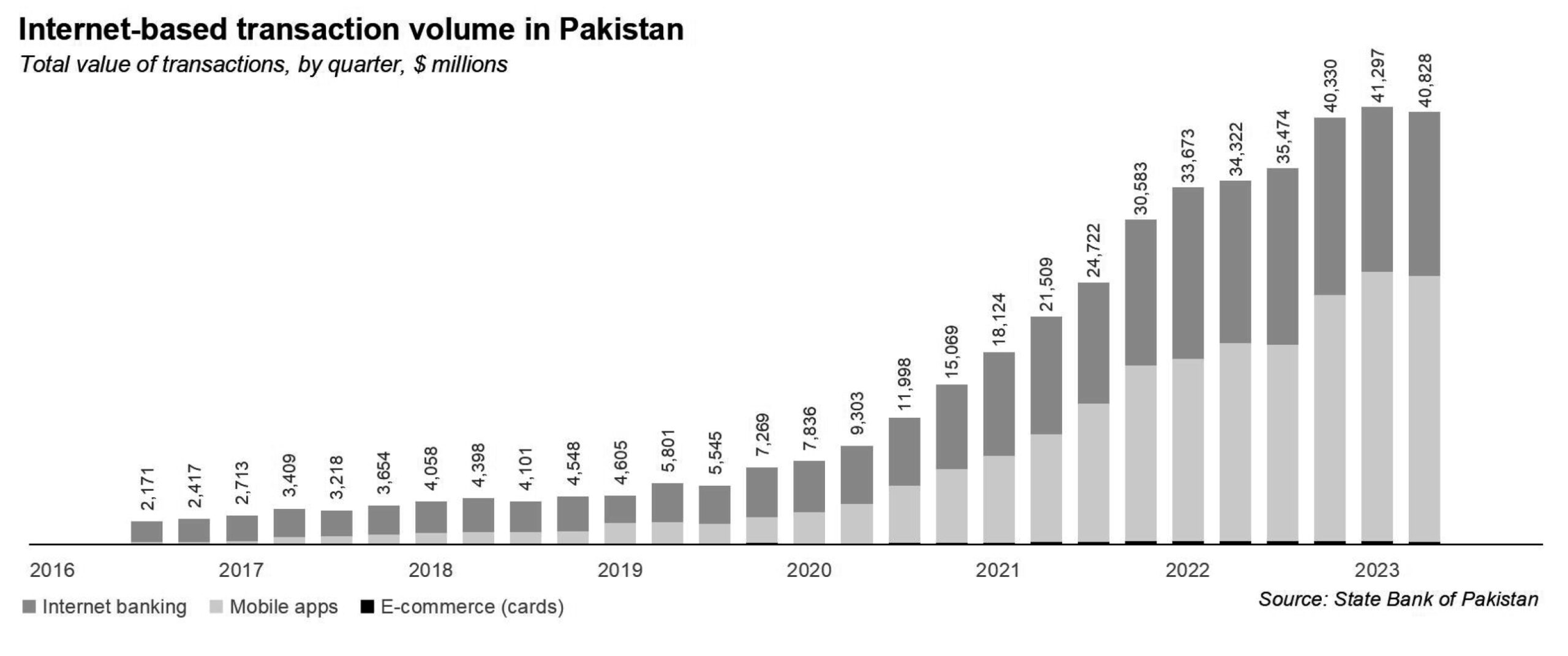

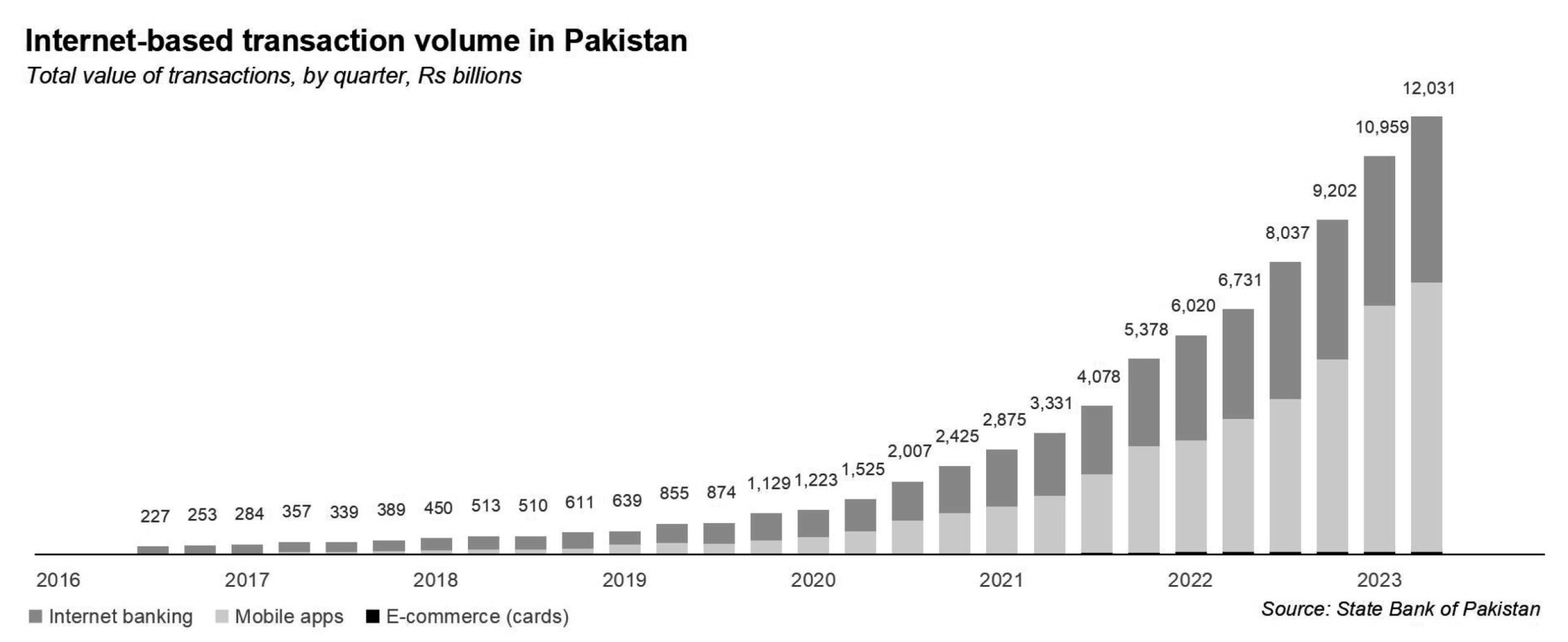

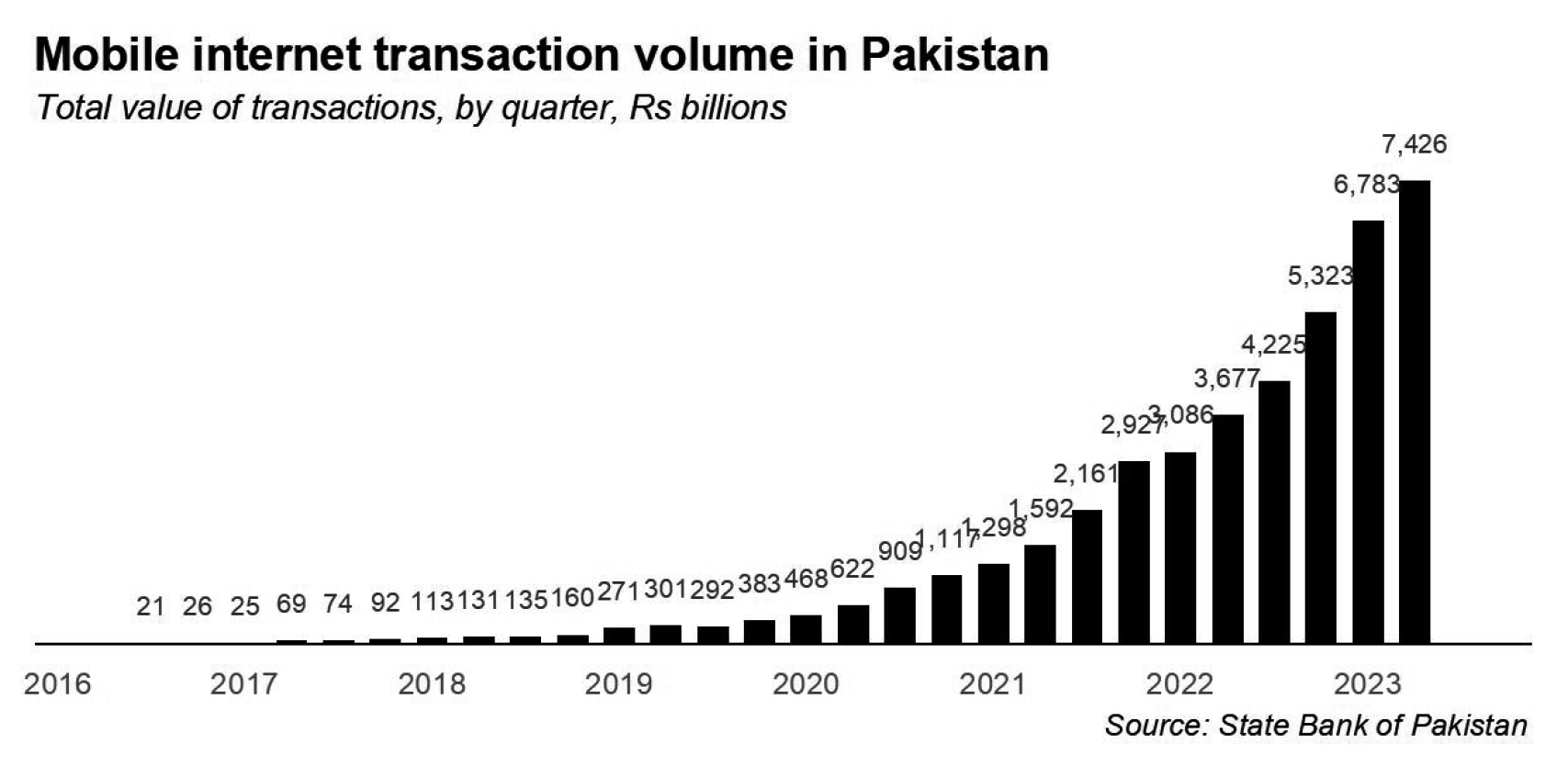

Bank mobile apps are the fastest-growing, with the total value of mobile app transactions growing by an average of 135% per year since 2016. It is getting to the point where bank apps are no longer just a niche that is posting high growth rates purely due to a low-base effect. For the fiscal year ending June 30, 2023, transactions initiated on mobile apps reached Rs23.7 trillion ($92.7 billion) in value. That means that every month, there are nearly Rs2 trillion ($7.7 billion) worth of transactions taking place, mostly at the beginning of the month, just off people’s mobile phones.

Transactions on the desktop websites of banks – which were a larger market than mobile apps as recently as the second quarter of 2021 – are the second-fastest growing, at an average rate of about 60% per year since 2016.

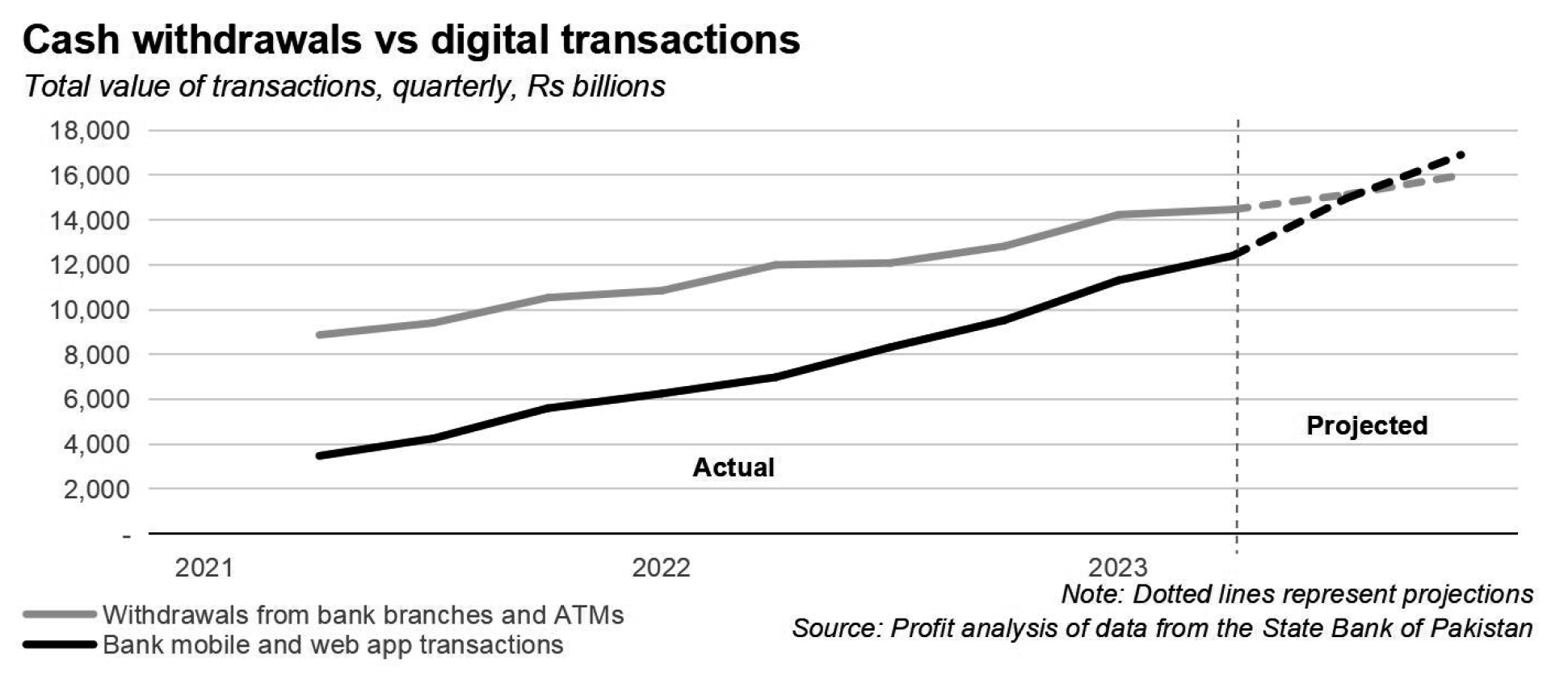

Bank websites and mobile apps are now rapidly becoming a favoured method by which Pakistanis transact. In the second quarter of 2023, the most recent period for which data is available, transactions worth Rs12.4 trillion ($40.7 billion) took place on bank websites and mobile apps. During that same period, total cash withdrawals from both bank branches and ATMs were only slightly higher, at about Rs 14.5 trillion ($49 billion). If current growth rates hold, we suspect that cash withdrawals from banks will be smaller than bank mobile and website transactions within the current quarter, and almost certainly by the end of the current fiscal year.

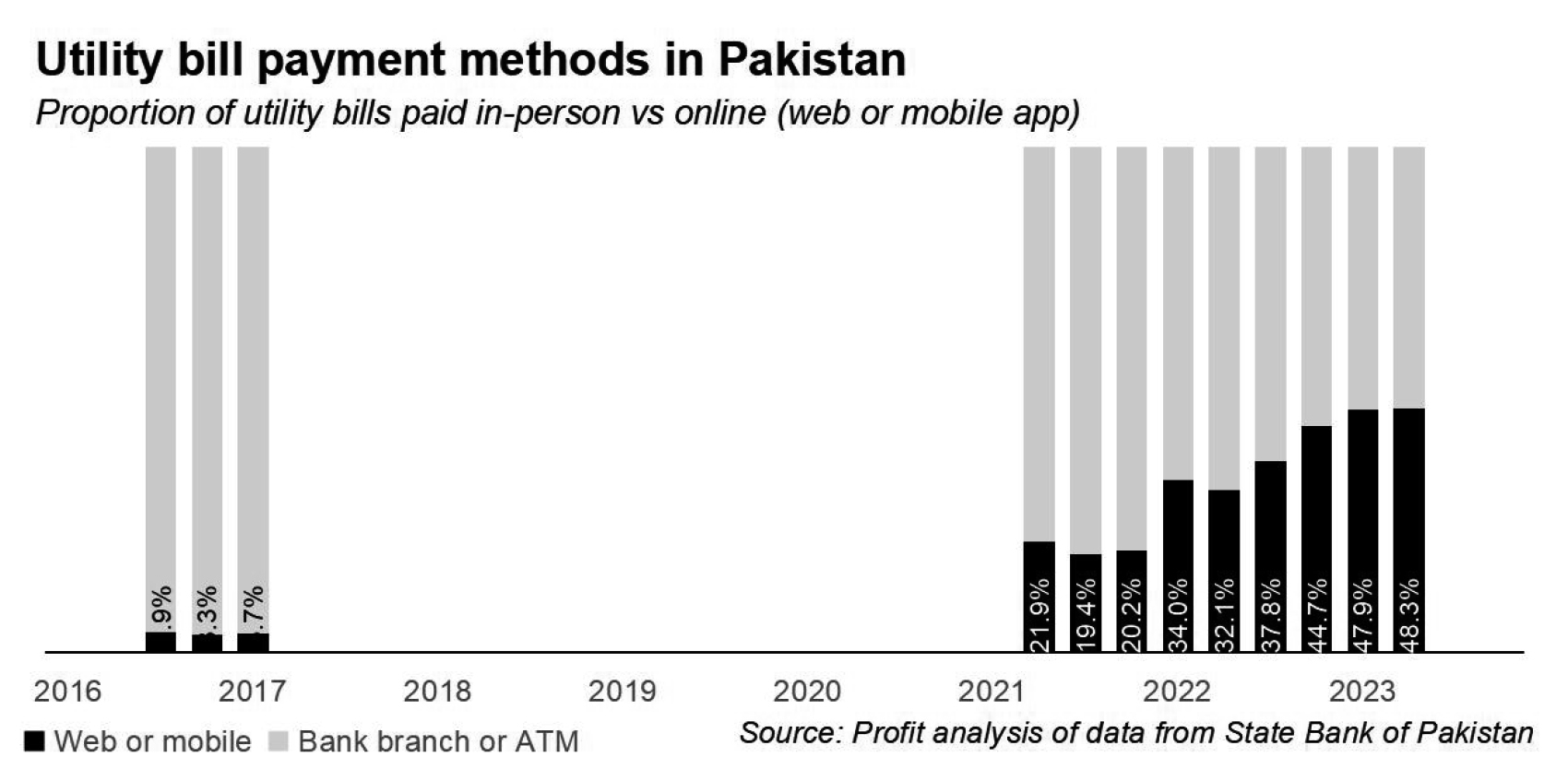

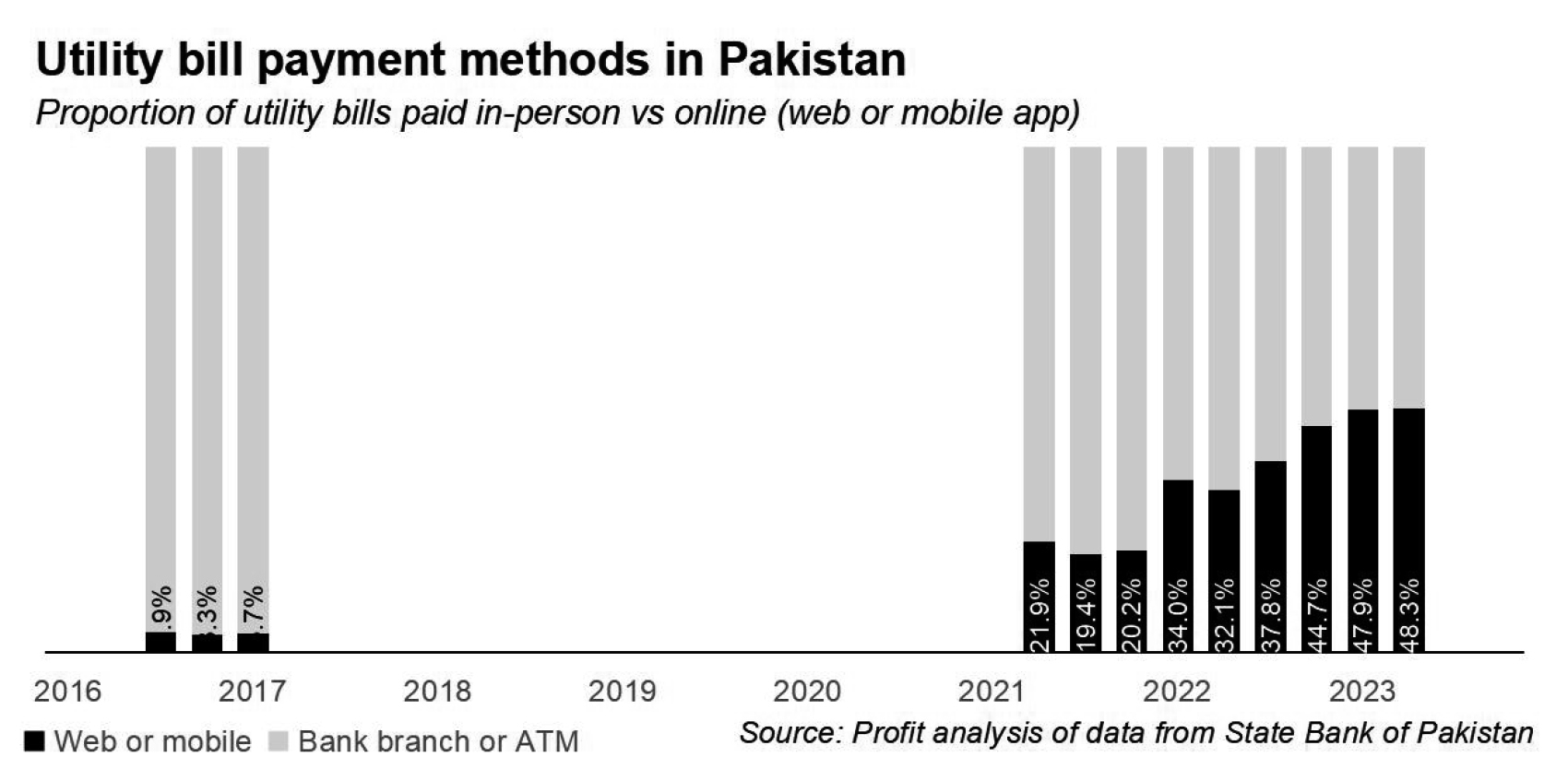

In some categories, consumers’ desire to transact online is quite high. For instance, about 48% of all utility bills in Pakistan by value were paid during the second quarter of 2023 on a bank website or a mobile app. That number was less than 4% in 2017.

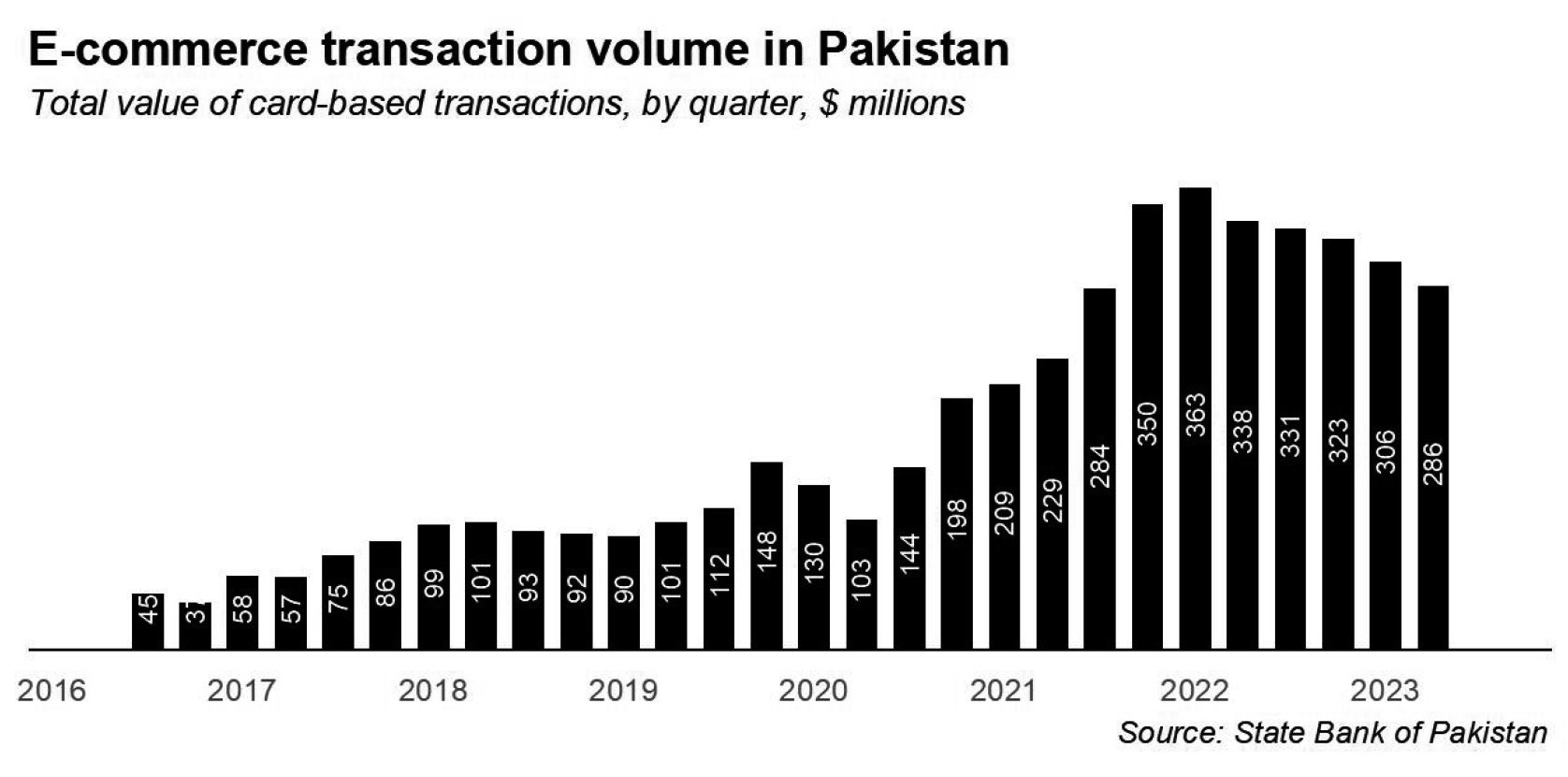

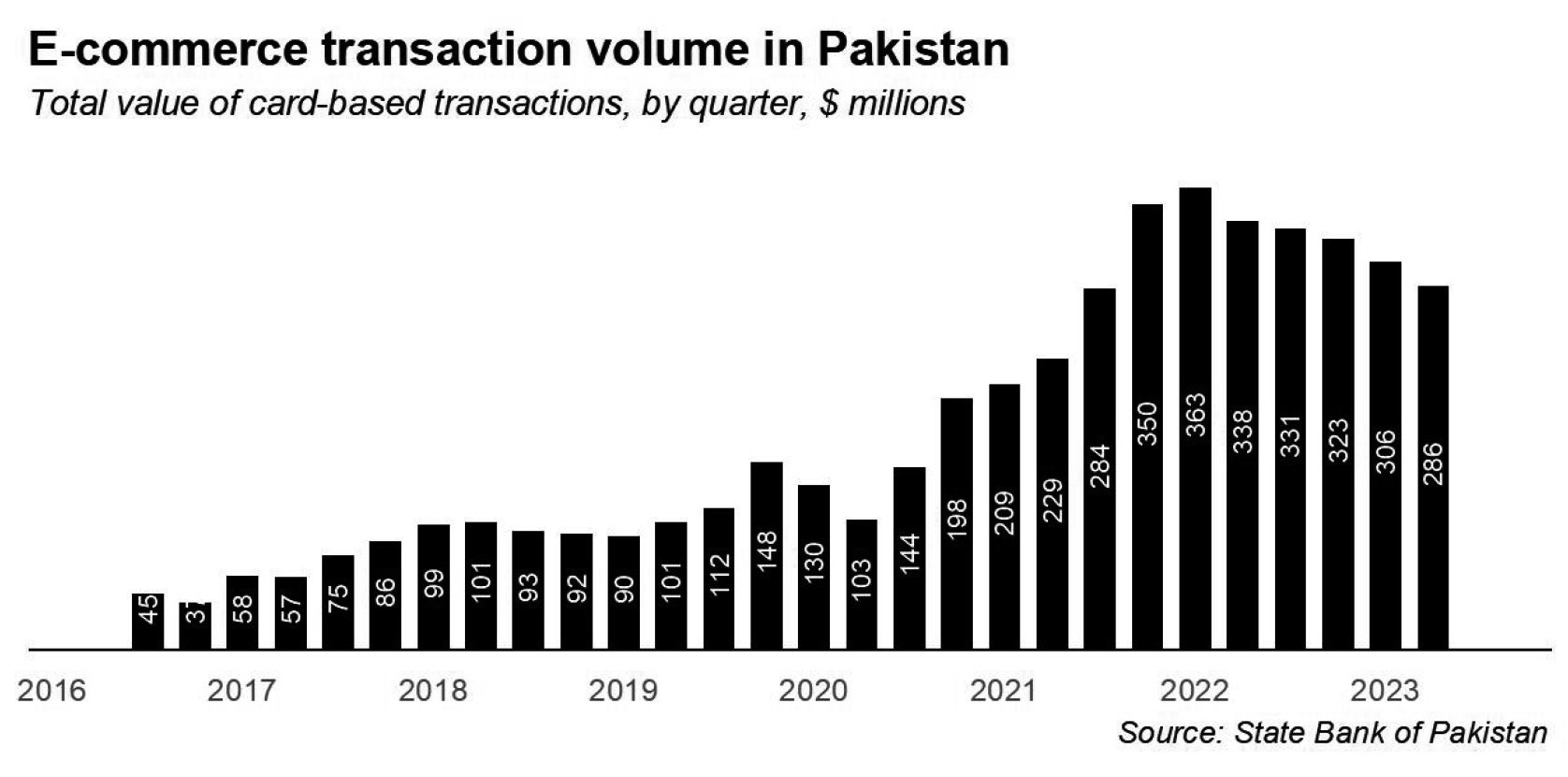

Card-based e-commerce – i.e. NOT cash on delivery – is growing at 57% per year, the electronic large retail and B2B transactions system at 35%, and physical card transactions at a point-of-sale (POS) machine at 28% per year.

The relative magnitude of these growth rates, and which ones are higher and lower tells us a lot about the state of mind of the Pakistani consumer, and what strategies might be applied for businesses that want to take advantage of this.

How we got here

I made my first e-commerce purchase in Pakistan in 2009, when I bought a book on the Liberty Books website and paid with a debit card. At the time, virtually everyone I knew told me I was stupid and that my card information would be leaked and my money would be stolen. That kind of thing does, of course, happen, but it did not happen to me.

Those kinds of concerns have largely receded into the background today. People still have a strong preference for cash-on-delivery, but it is not because they fear putting their card information into a website. They may be sceptical of merchants, but they trust the payments system, and for that, we must give the banks credit.

Pakistan is nowhere near where it needs to be in terms of availability and ease of electronic payments, but there is no denying that the progress has been impressive over the past five years. In a previous story on the subject, we mentioned the fact that the prevalence of 3G and 4G internet was a massive enabling factor in the rise of electronic payments.

We must add that both the State Bank of Pakistan and the banks have done a good job. The banks, pushed both by the State Bank and the payment networks (Visa and Mastercard), have helped the public gain trust in using cards online, in shops, and on ATMs. They have built largely secure websites and apps that – while being less than stellar in performance sometimes – are products that people feel they can trust to do the job well and, most importantly, not let their money get stolen.

This is not, in any way, to suggest that fraud does not happen or that hacks are not a concern. They are, but they have become rare enough that the public at large is not too frightened to use electronic means of transacting, and for that, the banks, the payment networks, and the central bank deserve credit.

And the fact that card-based e-commerce is also growing rapidly – albeit less rapidly than bank apps and websites – suggests that the horror stories of e-commerce notwithstanding, people are a bit more willing to trust e-commerce merchants than meets the eye.

One hypothesis that some people have put forward: people will pay cash-on-delivery for the first, or first few, orders from an e-commerce merchant. But once they establish trust, they will then place subsequent transactions using a debit or credit card.

Talk to e-commerce merchants and most insist that cash-on-delivery accounts for between 80-90% of their business, and for some it is even higher. We have no reason to believe this is not the case, but the fact that Pakistanis spent $564 million in fiscal year 2023 through their cards on Pakistani e-commerce websites and apps – and that this number has been growing at an average of 57% per year for the past 6 years – tells us that card-based e-commerce is not just a curiosity. People clearly wish they could trust e-commerce websites enough to use cards as their default payment method.

So how do we reconcile both of these data points: card-based payments are growing rapidly, but merchants say the proportion of their revenue coming from cash-on-delivery is about the same as it was in 2016. Only one explanation makes sense: e-commerce as a category is growing by that rapid rate.

An interesting question to which we tried to get an answer but have not yet found one: how much of this growth is coming from new users trying out e-commerce for the first time vs expanded spending by existing e-commerce customers? If we find data that answers that question, we will report back.

And after years of stalled growth, there now appears to be a sharp increase in transaction value for card payments at retail outlets. POS transactions were a relatively slow growing category between 2016 and 2020, but over the past three years have averaged about 54% annual growth.

What caused the sudden change? The number of POS machines. As of September 30, 2020, there were just shy of 53,000 POS machines deployed across all of Pakistan, a number that had grown at an embarrassing 1.2% per year for the previous four years. As of June 30 of this year, that number has more than doubled to 115,000 POS machines.

Intensifying competition amongst the banks and payments companies appears to be behind this increase, though the number of banks that offer POS machines – nine – has not changed during this period.

In short, this data is telling us that people in Pakistan largely trust the payment rails that help them transact electronically. When those rails are made more accessible, they will use them. They only pause when they do not trust the person on the other end of the transaction.

What comes next

So if you are a bank CEO or a startup founder, what should you take away from this? How can you take advantage of what is clearly the mother of all economic behavioural changes taking place in Pakistan today?

In our view, the answer is simple (even if its implications are complex): any business that is able to increase trust between transacting parties will build a winning business. This can take many forms, whether it be a high-service-quality e-commerce merchant, or a marketplace that insists on performing verifications of every merchant it allows onto its platform.

Or it could look like Safepay’s recurring payment feature.

To recall, Safepay is one of Pakistan’s leading fintech startups focused on enabling e-commerce merchants to accept electronic payments, and after spending at least two years working on it, they have finally been able to launch their recurring payment feature. It could, if used right, be a game-changer for Pakistan’s economy.

Why? Because it reduces the barriers to trust between any two transacting parties. By allowing the buyer to break up the payment they owe the seller into multiple smaller payments, each of which is automatically authorised when they set up the first payment, they are reducing the risk each party is taking on in transacting with the other.

The number of businesses that can be built on top of this is simply astounding. Here is a partial list of things that could potentially be built using this feature from Safepay. (Note to aspiring founders: some of these are startup ideas.)

Lowering the lump sum costs by breaking them up into predictable, automated monthly payments would increase trust. (Remember: lump sum payments are often the result of low trust to begin with. For example, in the case of annual rents for real estate.) It also, quite obviously, makes costs more manageable without necessarily decreasing them, thereby increasing market size.

And if banks were to allow recurring payments from bank accounts – and thereby avoid the 2.9% debit card fees – some more use cases would open up.

More broadly, increasing trust makes the country a less scary place. Every bit of fear that gets taken out of the economy is fear that we as individuals do not need to feel, and some of the clenched muscles that come from us being in a metaphorical crouch all our lives might unclench just a little bit, allowing us to breathe incrementally a bit easier.

profit.pakistantoday.com.pk

profit.pakistantoday.com.pk

Some time over the next 12 months, Pakistan’s economy will cross an important milestone: the total volume of transactions that people conduct using their credit and debit cards, their bank apps, and web portals will exceed the total amount of cash they withdraw from bank branches or ATMs. In other words, to make a payment, if you are one of those Pakistanis who has a bank account, you will be more likely to use a card or the internet than go get cash from the closest bank branch or ATM.

Cash is still very much king in Pakistan, accounting for about 37.2% of all transactions in the country (excluding interbank and government bond transactions) as of the second quarter of 2023, according to Profit’s analysis of data from the State Bank of Pakistan. But the myth that Pakistanis do not like transacting using electronic means needs to die. The evidence is in.

In fact, the question is not even whether and at what speed cash will go out of fashion. The most important question on this subject is how do business leaders take advantage of this shift that is already happening? Which payments companies or startups are poised to take advantage of this change? And given all of this, what effects can consumers expect to see in the scope of services that will be available to them?

It may be hard to see it now, given the incredibly difficult period that the Pakistani economy is still going through, but a tipping point has been reached and an exciting new stage of economic development is in the offing for Pakistan.

In this story, we will explore where we currently are with respect to the evolution of digital payments in Pakistan, how we got here, and what comes next.

Methodology of data analysis (feel free to skip)

A brief note on the data and methodology used in this article. The data comes from the State Bank of Pakistan’s quarterly and annual Payment Systems Review reports from the third quarter of calendar year 2016 through the second quarter of calendar year 2023. The reports extend much further back into the past as well, but the data appears to be compiled using a different methodology in prior years, and we included only data from the years where it seemed most directly comparable. Unless we specify otherwise, all growth rates mentioned in this article refer to the total value of transactions, not volume.

We also felt this was the most pertinent period to examine, since this is also the time when Pakistanis began to gain access to the internet in large numbers, following the auction of the 3G and 4G mobile broadband internet spectrum, which gave tens of millions of Pakistanis access to the internet for the first time.

Profit has not just compiled the data, but also combined it with other banking sector data to create as holistic a picture of payments in Pakistan as possible.

While the data for every other payment method is available in that report, what is not available is the volume of cash transactions that do not touch the banking system at either end (i.e. neither the giver nor the receiver of the cash is a banking or financial entity). While the volume of cash transactions is not directly measured by the State Bank of Pakistan, because it issues bank notes, it has a fairly good idea of exactly how much physical cash is in circulation at any given moment in time.

We made a simplifying assumption that the velocity of transactions involving physical cash is approximately the same as that involving the payments system in any given period. We are not certain as to how accurate this assumption is likely to be, but we also do not have a better number to go on.

Having calculated the total value of transactions involving cash, we then subtract from that the value of cash transactions involving the banks (ATM or branch withdrawals and deposits) to arrive at an estimate of the size of the cash-only transactions economy. This estimate is then plugged into any calculations involving market share of cash vs electronic payments.

One other note: we excluded interbank settlements and government bond transactions in our analysis, since those are transactions that are needed to keep the payments and banking system running. Counting them would likely end up double-counting many transactions and hence result in a skewed picture of what people are actually using to make their payments.

One final bit: we are putting in US dollar equivalents for many numbers in this story to help illustrate the scale of what we are talking about. Since almost all of the numbers involved represent flows over a period of time, we will adopt the convention of utilising the average exchange rate during that period, defined as the midpoint of the open market buying and selling exchange rates as published by Business Recorder.

The current state of play in payments

Take a look at where the current state of payments is in Pakistan, and you will notice the absolute dominance of cash. About 37.2% of transactions are cash-only – meaning they do not interact with the banking system on either the payer or receiver side. Another 11.8% are deposits and withdrawals from bank branches, and a further 1.6% are withdrawals and deposits at ATMs. All told, the total amount of transactions involving physical cash is about 50.7% of the value of all transactions in the country.

Indeed, purely electronic transactions account for just 15.9% of the value of all transactions in the country. (The bulk of the remainder is taken up by things like cheques, and other paper instruments.) But take a look at the growth rates and it becomes clear that growth in payments is coming largely from electronic payment methods, with cash and paper slowly but surely losing ground.

On the chart of the growth rates in payment value by payment type, all of the top five spots are taken up by internet-based methods.

Bank mobile apps are the fastest-growing, with the total value of mobile app transactions growing by an average of 135% per year since 2016. It is getting to the point where bank apps are no longer just a niche that is posting high growth rates purely due to a low-base effect. For the fiscal year ending June 30, 2023, transactions initiated on mobile apps reached Rs23.7 trillion ($92.7 billion) in value. That means that every month, there are nearly Rs2 trillion ($7.7 billion) worth of transactions taking place, mostly at the beginning of the month, just off people’s mobile phones.

Transactions on the desktop websites of banks – which were a larger market than mobile apps as recently as the second quarter of 2021 – are the second-fastest growing, at an average rate of about 60% per year since 2016.

Bank websites and mobile apps are now rapidly becoming a favoured method by which Pakistanis transact. In the second quarter of 2023, the most recent period for which data is available, transactions worth Rs12.4 trillion ($40.7 billion) took place on bank websites and mobile apps. During that same period, total cash withdrawals from both bank branches and ATMs were only slightly higher, at about Rs 14.5 trillion ($49 billion). If current growth rates hold, we suspect that cash withdrawals from banks will be smaller than bank mobile and website transactions within the current quarter, and almost certainly by the end of the current fiscal year.

In some categories, consumers’ desire to transact online is quite high. For instance, about 48% of all utility bills in Pakistan by value were paid during the second quarter of 2023 on a bank website or a mobile app. That number was less than 4% in 2017.

Card-based e-commerce – i.e. NOT cash on delivery – is growing at 57% per year, the electronic large retail and B2B transactions system at 35%, and physical card transactions at a point-of-sale (POS) machine at 28% per year.

The relative magnitude of these growth rates, and which ones are higher and lower tells us a lot about the state of mind of the Pakistani consumer, and what strategies might be applied for businesses that want to take advantage of this.

How we got here

I made my first e-commerce purchase in Pakistan in 2009, when I bought a book on the Liberty Books website and paid with a debit card. At the time, virtually everyone I knew told me I was stupid and that my card information would be leaked and my money would be stolen. That kind of thing does, of course, happen, but it did not happen to me.

Those kinds of concerns have largely receded into the background today. People still have a strong preference for cash-on-delivery, but it is not because they fear putting their card information into a website. They may be sceptical of merchants, but they trust the payments system, and for that, we must give the banks credit.

Pakistan is nowhere near where it needs to be in terms of availability and ease of electronic payments, but there is no denying that the progress has been impressive over the past five years. In a previous story on the subject, we mentioned the fact that the prevalence of 3G and 4G internet was a massive enabling factor in the rise of electronic payments.

We must add that both the State Bank of Pakistan and the banks have done a good job. The banks, pushed both by the State Bank and the payment networks (Visa and Mastercard), have helped the public gain trust in using cards online, in shops, and on ATMs. They have built largely secure websites and apps that – while being less than stellar in performance sometimes – are products that people feel they can trust to do the job well and, most importantly, not let their money get stolen.

This is not, in any way, to suggest that fraud does not happen or that hacks are not a concern. They are, but they have become rare enough that the public at large is not too frightened to use electronic means of transacting, and for that, the banks, the payment networks, and the central bank deserve credit.

And the fact that card-based e-commerce is also growing rapidly – albeit less rapidly than bank apps and websites – suggests that the horror stories of e-commerce notwithstanding, people are a bit more willing to trust e-commerce merchants than meets the eye.

One hypothesis that some people have put forward: people will pay cash-on-delivery for the first, or first few, orders from an e-commerce merchant. But once they establish trust, they will then place subsequent transactions using a debit or credit card.

Talk to e-commerce merchants and most insist that cash-on-delivery accounts for between 80-90% of their business, and for some it is even higher. We have no reason to believe this is not the case, but the fact that Pakistanis spent $564 million in fiscal year 2023 through their cards on Pakistani e-commerce websites and apps – and that this number has been growing at an average of 57% per year for the past 6 years – tells us that card-based e-commerce is not just a curiosity. People clearly wish they could trust e-commerce websites enough to use cards as their default payment method.

So how do we reconcile both of these data points: card-based payments are growing rapidly, but merchants say the proportion of their revenue coming from cash-on-delivery is about the same as it was in 2016. Only one explanation makes sense: e-commerce as a category is growing by that rapid rate.

An interesting question to which we tried to get an answer but have not yet found one: how much of this growth is coming from new users trying out e-commerce for the first time vs expanded spending by existing e-commerce customers? If we find data that answers that question, we will report back.

And after years of stalled growth, there now appears to be a sharp increase in transaction value for card payments at retail outlets. POS transactions were a relatively slow growing category between 2016 and 2020, but over the past three years have averaged about 54% annual growth.

What caused the sudden change? The number of POS machines. As of September 30, 2020, there were just shy of 53,000 POS machines deployed across all of Pakistan, a number that had grown at an embarrassing 1.2% per year for the previous four years. As of June 30 of this year, that number has more than doubled to 115,000 POS machines.

Intensifying competition amongst the banks and payments companies appears to be behind this increase, though the number of banks that offer POS machines – nine – has not changed during this period.

In short, this data is telling us that people in Pakistan largely trust the payment rails that help them transact electronically. When those rails are made more accessible, they will use them. They only pause when they do not trust the person on the other end of the transaction.

What comes next

So if you are a bank CEO or a startup founder, what should you take away from this? How can you take advantage of what is clearly the mother of all economic behavioural changes taking place in Pakistan today?

In our view, the answer is simple (even if its implications are complex): any business that is able to increase trust between transacting parties will build a winning business. This can take many forms, whether it be a high-service-quality e-commerce merchant, or a marketplace that insists on performing verifications of every merchant it allows onto its platform.

Or it could look like Safepay’s recurring payment feature.

To recall, Safepay is one of Pakistan’s leading fintech startups focused on enabling e-commerce merchants to accept electronic payments, and after spending at least two years working on it, they have finally been able to launch their recurring payment feature. It could, if used right, be a game-changer for Pakistan’s economy.

Why? Because it reduces the barriers to trust between any two transacting parties. By allowing the buyer to break up the payment they owe the seller into multiple smaller payments, each of which is automatically authorised when they set up the first payment, they are reducing the risk each party is taking on in transacting with the other.

The number of businesses that can be built on top of this is simply astounding. Here is a partial list of things that could potentially be built using this feature from Safepay. (Note to aspiring founders: some of these are startup ideas.)

- Rental payments: A web portal that allows landlords to collect rent from their tenants on a monthly basis rather than insisting on annual rent being paid up front, which many prospective tenants find difficult. By making monthly payments the norm, the size of the population that can consider renting their own place would increase, which would reduce the vacancy rates on rental properties.

- Insurance: Instead of having to pay annual premiums, insurance company clients could pay monthly premiums, which would increase the market size by allowing more people to try out insurance.

- BNPL: Buy-now-pay-later companies can substantially reduce their risk by allowing users to enter recurring payment authorizations on their debit cards, which would lower at least some of the default risk.

- Services professionals’ fees: Imagine being able to pay a lawyer, an accountant, or an advertising agency their fees in smaller instalments, all authorised as recurring payments on a debit card. Payments for such services would feel more manageable, more people and businesses would feel they could afford them, and the service professionals in these fields which are notorious for low pay that often comes late will find higher and more predictable cash flows.

Lowering the lump sum costs by breaking them up into predictable, automated monthly payments would increase trust. (Remember: lump sum payments are often the result of low trust to begin with. For example, in the case of annual rents for real estate.) It also, quite obviously, makes costs more manageable without necessarily decreasing them, thereby increasing market size.

And if banks were to allow recurring payments from bank accounts – and thereby avoid the 2.9% debit card fees – some more use cases would open up.

- Automated car loan and mortgage repayments: Banks could reduce a significant portion of their repayment risks on car loans and mortgages if they stopped resisting the attempts by 1Link and others to implement a recurring payment feature in bank accounts. It would open up their lending book to all banking customers, instead of just the customers of their banks, and in turn would increase their ability to grow these business lines.

- Systematic investment plans: This would allow people to deposit money into mutual fund or brokerage accounts at a regular cadence, allowing them to systematically invest their money and ensure that they could build up wealth for themselves and their families.

More broadly, increasing trust makes the country a less scary place. Every bit of fear that gets taken out of the economy is fear that we as individuals do not need to feel, and some of the clenched muscles that come from us being in a metaphorical crouch all our lives might unclench just a little bit, allowing us to breathe incrementally a bit easier.

Die, cash, die!

The Pakistani middle class is past its scepticism of electronic money. How did we get here, and what comes next?

profit.pakistantoday.com.pk

profit.pakistantoday.com.pk