walterbibikow

BANNED

- Joined

- Nov 12, 2022

- Messages

- 940

- Reaction score

- -4

- Country

- Location

South Asia’s Brahmaputra has been cited as one of the basins most at risk for interstate water conflict. While violent conflict has occurred between China and India within the Brahmaputra’s basin boundaries, the risks of conflict over water are in fact low. This is in part because China functionally contributes less to the Brahmaputra’s flow than is commonly perceived and in part because, despite its massive volume, the river can contribute little to solving India’s significant water security challenges. Nonetheless, the Brahmaputra is and will continue to be intimately connected to Sino-Indian tensions largely through the use of water infrastructure investment as a form of territorial demarcation and control.

An elderly man carries a bamboo pole and a baby across a stream of the Brahmaputra river, Dholpur, India on Sept. 28, 2021. (Karan Deep Singh/The New York Times)

The Water Wars Theory and Brahmaputra Basin Realities

A simplified version of the water wars argument is that per capita water availability will drop as populations grow and water supplies remain constant. At the same time, economic growth will multiply demand as effective supplies are reduced with quality declines. Climate change will only worsen the situation. For internationally shared rivers, conflict over the vital resource will occur when some tipping point is reached, particularly if tensions over other issues are high and there is no history of institutionalizing cooperation over water through treaties or other mechanisms.

The Brahmaputra would appear to be at the top of the list of conflict hotspots. The river is shared between four states, including the world’s two most populous, China and India. Both have rapidly growing economies and both are already among the most water stressed in the world. The challenges for cooperatively managing the Brahmaputra are heightened by a changing monsoon season and melting glaciers, the complete absence of formal water sharing agreements, a limited history of even basic hydrologic data exchange and strained diplomatic relations. In addition, China has shown little interest in cooperative transboundary water management in the Brahmaputra or elsewhere. As the upstream state, China controls more than half the Brahmaputra basin’s area and is building infrastructure — in particular dams — to control water without consultation with downstream neighbors.

To understand why, despite these factors, water conflict is less likely than commonly perceived, it is important to understand the hydrology of the Brahmaputra basin and its overall context. While China controls most of the basin’s area, most of that area lies in a rain shadow, formed when monsoon winds rise over Himalayan peaks and then descend again onto the Tibetan Plateau. In contrast, the Indian, Bhutanese and Bangladeshi portions of the basin lie in some of the world’s highest precipitation areas, with rainfall consistently above 98 inches per year. In fact, the state of Meghalaya, in the Indian portion of the basin, is often referenced as the wettest place in the world, with 433 inches of annual precipitation in some areas.

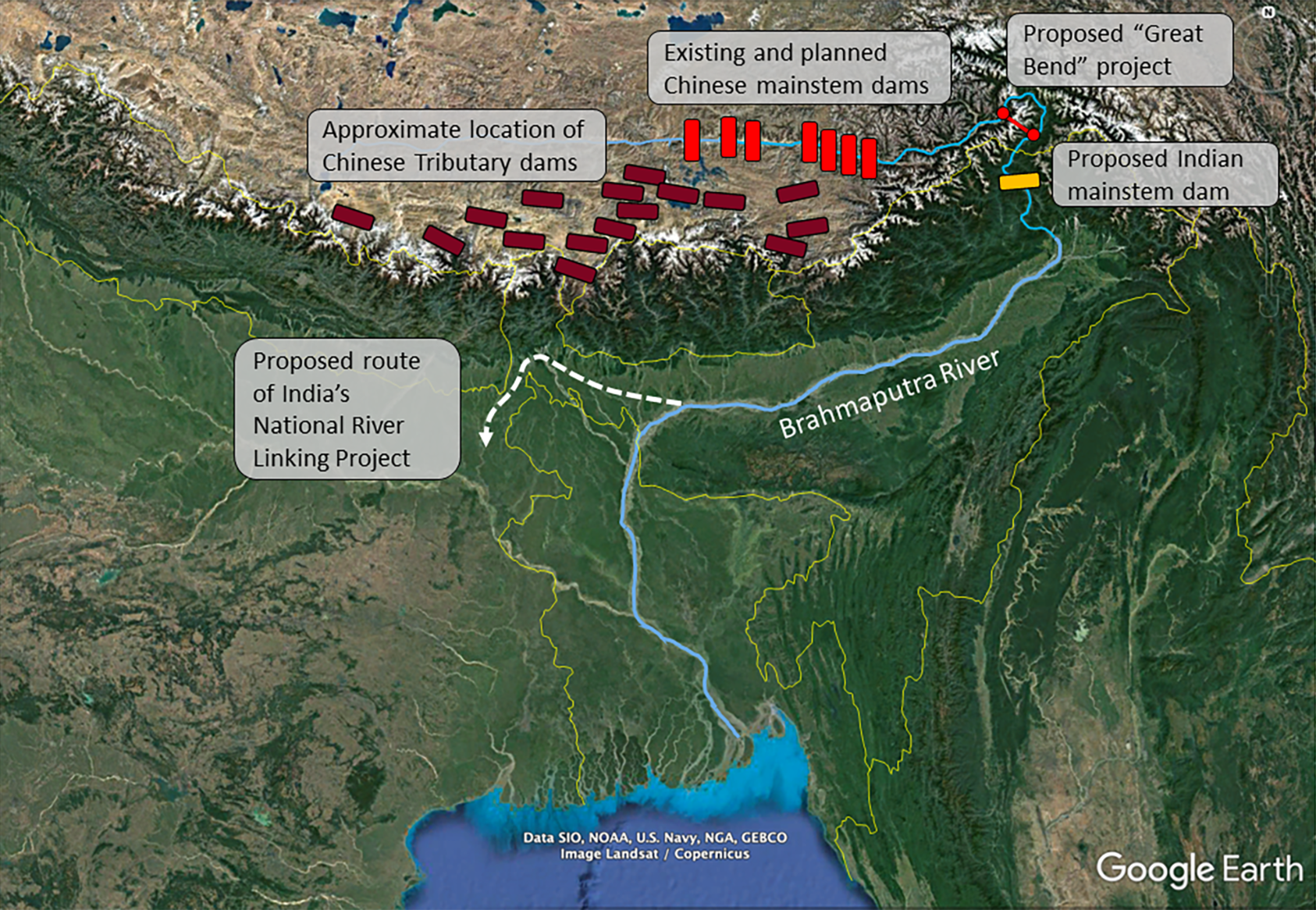

Existing and planned Infrastructure on the Brahmaputra

As a result, China’s contribution to overall flow is undoubtedly lower than its share of basin area. How much lower is unclear, however, because of limited gauging stations and access to what data might exist (even within India, water data is not consistently shared between and across government levels). The result has been that both public and policy discussion about Sino-Indian water relations have relied on a limited number of poorly attributed and understood statistics. At one extreme, figures from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) put China’s contribution to Brahmaputra flow at 30% while at the other anonymous Government of India sources put the figure at 7%. Both figures have been cited to support differing positions.

To provide context for such figures, we compiled data from a range of sources and computed China’s implied contribution to flow along the Brahmaputra’s course. From this work, it appears that the FAO figure is based on estimates of all Brahmaputra basin waters entering India from China (the Brahmaputra mainstem and tributaries including the Lohit and Subashiri) as a share of the Brahmaputra’s flow at Guwahati, about 75 miles from the border with Bangladesh. The Government of India’s 7% figure appears to include only water entering India from China via the Brahmaputra’s mainstem (i.e., excluding tributaries, as a percentage of all Brahmaputra flow up to the confluence of the Padma/Ganges in Bangladesh). Since China’s infrastructure development is and will continue to be limited to its mainstem waters, the 30% figure, by including flows from other tributaries, overstates China’s hydrologic advantage and potential leverage over India. In contrast, the 7% figure underestimates it, by including flows that enter the Brahmaputra in Bangladesh.

While the appropriate figure to use depends on its purpose, any focus on China’s contributions to flow detracts from an understanding of the larger context in which the Brahmaputra basin must be seen. Since the Indian portion of the basin is in one of the highest rainfall regions in the world, India has little need to draw from the river now or in the future for agriculture or other purposes. Even India’s most grandiose plans to transfer water out of the basin to more arid areas would have little impact on total flow because of the Brahmaputra’s great volume.

Given China’s limited contribution to flow and the lack of capacity for the Brahmaputra’s waters to alleviate India’s water insecurity, conflict over water per se is unlikely. Climate change is expected to intensify the hydrological cycle. In this case, as temperatures rise, precipitation is expected to increase in the basin, due to a decrease on the Tibetan Plateau (China’s portion of the basin), which is more than offset by increases elsewhere. As such, increased temperatures are expected to increase flow, reduce glacial mass within China and, eventually, lower China’s contribution to flow.

Competition Through Water Infrastructure

While the competition between China and India over the quantity of Brahmaputra water may not be significant, another form of competition is manifesting itself through water infrastructure. China’s first project in the basin was a hydropower station completed in 1998. China has since built or is planning a series of publicly discussed dams on the Brahmaputra mainstem. An additional 18 dams on mainstem tributaries have been identified with satellite imagery by the Stimson Center’s Energy, Water, and Sustainability Program and Planet Labs. Of all the additional dams under discussion, by far the most ambitious and controversial is the “Great Bend Dam,” which would divert water through a tunnel with a 6,562-foot drop, generating twice the power of China’s famed Three Gorges dam.

Even if Chinese infrastructure is not designed to withdraw water from the river, it does have the potential to impact the timing of flows, potentially increasing flood risk. But coordinated operation with India could also be a means for decreasing flood risks. The Government of India has historically downplayed risks from Chinese infrastructure, sometimes citing the minimal 7% of flow contributed by China mentioned above. However, this stance recently changed, as evidenced by a 2020 announcement by the Ministry of Water Resources to build a 10-gigawatt hydropower project on the Brahmaputra, specifically to “mitigate the adverse impact of the Chinese dam projects.” Part of the rationale was given as creating storage capacity to mitigate the negative effects of Chinese dam operations. Though framed in terms hydropower production and flood control, water infrastructure in the Brahmaputra also serves as a form of territorial demarcation and control along a contested frontier. As one Indian official stated in 2016 with respect to one of China’s dams, “The strategic value of the Lalho project lies also in the fact that Shigatse is only a few hours driving distance from the junction of Bhutan and Sikkim, and the city from which the Chinese plan to extend their railroads to Nepal.” The Great Bend Dam, if constructed, would for the first time move Chinese infrastructure off the Tibetan Plateau onto the southern slopes of the Himalaya toward the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh, a region China calls “South Tibet.” India, for its part, would place its mega-dam near its border with China, likewise signaling control of not only water but territory. The Indian megadam is also part of larger planning begun in the early 2000s for up to 150 dams within Arunachal Pradesh.

www.usip.org

www.usip.org

@Skull and Bones @Raj-Hindustani @VkdIndian @INDIAPOSITIVE @LakeHawk180

An elderly man carries a bamboo pole and a baby across a stream of the Brahmaputra river, Dholpur, India on Sept. 28, 2021. (Karan Deep Singh/The New York Times)

The Water Wars Theory and Brahmaputra Basin Realities

A simplified version of the water wars argument is that per capita water availability will drop as populations grow and water supplies remain constant. At the same time, economic growth will multiply demand as effective supplies are reduced with quality declines. Climate change will only worsen the situation. For internationally shared rivers, conflict over the vital resource will occur when some tipping point is reached, particularly if tensions over other issues are high and there is no history of institutionalizing cooperation over water through treaties or other mechanisms.

The Brahmaputra would appear to be at the top of the list of conflict hotspots. The river is shared between four states, including the world’s two most populous, China and India. Both have rapidly growing economies and both are already among the most water stressed in the world. The challenges for cooperatively managing the Brahmaputra are heightened by a changing monsoon season and melting glaciers, the complete absence of formal water sharing agreements, a limited history of even basic hydrologic data exchange and strained diplomatic relations. In addition, China has shown little interest in cooperative transboundary water management in the Brahmaputra or elsewhere. As the upstream state, China controls more than half the Brahmaputra basin’s area and is building infrastructure — in particular dams — to control water without consultation with downstream neighbors.

To understand why, despite these factors, water conflict is less likely than commonly perceived, it is important to understand the hydrology of the Brahmaputra basin and its overall context. While China controls most of the basin’s area, most of that area lies in a rain shadow, formed when monsoon winds rise over Himalayan peaks and then descend again onto the Tibetan Plateau. In contrast, the Indian, Bhutanese and Bangladeshi portions of the basin lie in some of the world’s highest precipitation areas, with rainfall consistently above 98 inches per year. In fact, the state of Meghalaya, in the Indian portion of the basin, is often referenced as the wettest place in the world, with 433 inches of annual precipitation in some areas.

Existing and planned Infrastructure on the Brahmaputra

As a result, China’s contribution to overall flow is undoubtedly lower than its share of basin area. How much lower is unclear, however, because of limited gauging stations and access to what data might exist (even within India, water data is not consistently shared between and across government levels). The result has been that both public and policy discussion about Sino-Indian water relations have relied on a limited number of poorly attributed and understood statistics. At one extreme, figures from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) put China’s contribution to Brahmaputra flow at 30% while at the other anonymous Government of India sources put the figure at 7%. Both figures have been cited to support differing positions.

To provide context for such figures, we compiled data from a range of sources and computed China’s implied contribution to flow along the Brahmaputra’s course. From this work, it appears that the FAO figure is based on estimates of all Brahmaputra basin waters entering India from China (the Brahmaputra mainstem and tributaries including the Lohit and Subashiri) as a share of the Brahmaputra’s flow at Guwahati, about 75 miles from the border with Bangladesh. The Government of India’s 7% figure appears to include only water entering India from China via the Brahmaputra’s mainstem (i.e., excluding tributaries, as a percentage of all Brahmaputra flow up to the confluence of the Padma/Ganges in Bangladesh). Since China’s infrastructure development is and will continue to be limited to its mainstem waters, the 30% figure, by including flows from other tributaries, overstates China’s hydrologic advantage and potential leverage over India. In contrast, the 7% figure underestimates it, by including flows that enter the Brahmaputra in Bangladesh.

While the appropriate figure to use depends on its purpose, any focus on China’s contributions to flow detracts from an understanding of the larger context in which the Brahmaputra basin must be seen. Since the Indian portion of the basin is in one of the highest rainfall regions in the world, India has little need to draw from the river now or in the future for agriculture or other purposes. Even India’s most grandiose plans to transfer water out of the basin to more arid areas would have little impact on total flow because of the Brahmaputra’s great volume.

Given China’s limited contribution to flow and the lack of capacity for the Brahmaputra’s waters to alleviate India’s water insecurity, conflict over water per se is unlikely. Climate change is expected to intensify the hydrological cycle. In this case, as temperatures rise, precipitation is expected to increase in the basin, due to a decrease on the Tibetan Plateau (China’s portion of the basin), which is more than offset by increases elsewhere. As such, increased temperatures are expected to increase flow, reduce glacial mass within China and, eventually, lower China’s contribution to flow.

Competition Through Water Infrastructure

While the competition between China and India over the quantity of Brahmaputra water may not be significant, another form of competition is manifesting itself through water infrastructure. China’s first project in the basin was a hydropower station completed in 1998. China has since built or is planning a series of publicly discussed dams on the Brahmaputra mainstem. An additional 18 dams on mainstem tributaries have been identified with satellite imagery by the Stimson Center’s Energy, Water, and Sustainability Program and Planet Labs. Of all the additional dams under discussion, by far the most ambitious and controversial is the “Great Bend Dam,” which would divert water through a tunnel with a 6,562-foot drop, generating twice the power of China’s famed Three Gorges dam.

Even if Chinese infrastructure is not designed to withdraw water from the river, it does have the potential to impact the timing of flows, potentially increasing flood risk. But coordinated operation with India could also be a means for decreasing flood risks. The Government of India has historically downplayed risks from Chinese infrastructure, sometimes citing the minimal 7% of flow contributed by China mentioned above. However, this stance recently changed, as evidenced by a 2020 announcement by the Ministry of Water Resources to build a 10-gigawatt hydropower project on the Brahmaputra, specifically to “mitigate the adverse impact of the Chinese dam projects.” Part of the rationale was given as creating storage capacity to mitigate the negative effects of Chinese dam operations. Though framed in terms hydropower production and flood control, water infrastructure in the Brahmaputra also serves as a form of territorial demarcation and control along a contested frontier. As one Indian official stated in 2016 with respect to one of China’s dams, “The strategic value of the Lalho project lies also in the fact that Shigatse is only a few hours driving distance from the junction of Bhutan and Sikkim, and the city from which the Chinese plan to extend their railroads to Nepal.” The Great Bend Dam, if constructed, would for the first time move Chinese infrastructure off the Tibetan Plateau onto the southern slopes of the Himalaya toward the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh, a region China calls “South Tibet.” India, for its part, would place its mega-dam near its border with China, likewise signaling control of not only water but territory. The Indian megadam is also part of larger planning begun in the early 2000s for up to 150 dams within Arunachal Pradesh.

The Water Wars Myth: India, China and the Brahmaputra

South Asia’s Brahmaputra has been cited as one of the basins most at risk for interstate water conflict. While violent conflict has occurred between China and India within the Brahmaputra’s basin boundaries, the risks of conflict over water are in fact low. This is in part because China...

@Skull and Bones @Raj-Hindustani @VkdIndian @INDIAPOSITIVE @LakeHawk180

Last edited: