Naif al Hilali

FULL MEMBER

- Joined

- Nov 5, 2016

- Messages

- 324

- Reaction score

- 24

- Country

- Location

Next story

The Legend of the Vietnam War’s Mystery Fighter Ace

Joseph Trevithick

Freelance Journalist for @warisboring and others, Historian, and Military Analyst. @franticgoat on Twitter

19 hrs ago

General Electric’s modified M-61 cannon sticks out the side of a UH-1B. U.S. Army photo via Ray Wilhite

The U.S. Army Kept Trying to Give the Huey Bigger Guns

It never worked

by JOSEPH TREVITHICK

A some point during the Vietnam War, a U.S. Army specialist named David drew up a plan to give UH-1 Huey helicopters more firepower. During the conflict, the Hueys relied primarily on 7.62-millimeter machine guns — including fast-firing Miniguns — and unguided rockets.

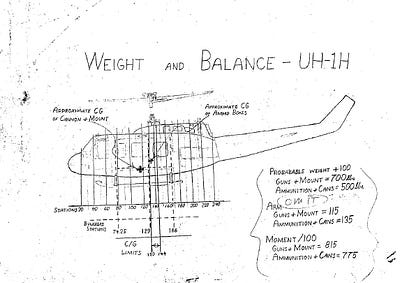

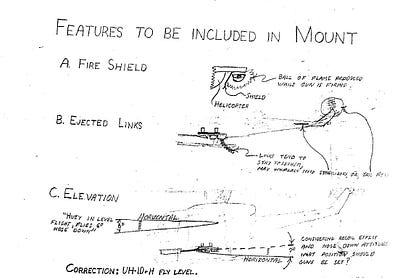

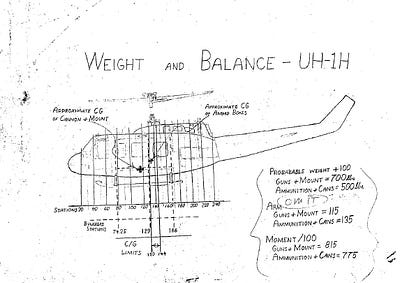

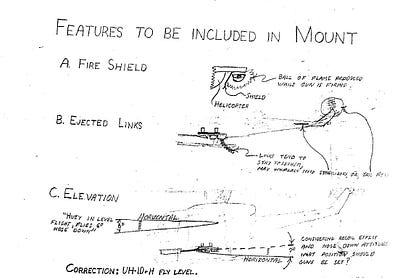

In his hand-drawn concept, the soldier proposed adding two significantly larger 20-millimeter cannons to a UH-1H troop-carrier. Though the whole system would likely weigh more than 1,200 pounds with a full load of ammunition, technicians would attach it close to the Huey’s center of gravity so as not to throw the chopper off balance.

The setup would have a “solid frame built around [the] helicopter to absorb most of the torque vibration,” the last page in his proposal explained. “The rubber is to absorb high-frequency vibrations.”

We don’t know David’s last name. He wrote it in the corner of all of his diagrams, but it’s illegible in the scanned copy Texas Tech University placed in the online Virtual Vietnam Archive.

The weapon system’s moniker, “XM-188,” isn’t official and was likely a reference to a military unit. The artwork is in a collection of documents related to the 1st Aviation Brigade, which included the 188th Assault Helicopter Company. The setup has no relation whatsoever to the later XM-188 30-millimeter cannon.

We don’t know if David or anyone else in the 188th ever built a working version. What we do know is that the Army had tried repeatedly to give the Huey bigger guns.

It never worked.

David’s XM-188 proposal. U.S. Army art via the Vietnam Center and Archive at Texas Tech University

By the time the Army put its first UH-1s into service in 1959, the notion of armed helicopters had finally started gaining traction. Unfortunately, no one knew what weapons would be suitable or appropriate for the new gunships.

During a series of experiments, Army test crews flew choppers with machine guns, automatic cannon, rockets, guided missiles and more. In 1956, General Electric had cooked up one of the very first helicopter weapon systems from a drawing on a napkin.

In October 1961, the Army went back to the Vermont-based manufacturing giant with a new request — install the 20-millimeter M-61 Vulcan cannon on the Huey. Within two months, the company’s engineers had a put together a detailed plan.

The hard-hitting, six-barrel Gatling gun was already standard armament for U.S. Air Force fighter jets and bombers. The M-61 could also fire several different rounds including high-explosive and incendiary cartridges.

“The M-61 gun is considered by the U.S. Air Force and Army Ordnance as the most reliable machine gun produced,” General Electric bragged in its brochure. War Is Boring found a copy of this document in the National Air and Space Museum Archives.

The firm’s engineers proposed bolting the M-61 high on the left side, in line with the chopper’s center of gravity. An ammunition magazine with 500 rounds in the main cabin would help even out the weight of the 800 pound setup. Since the Vulcan needed electricity to run, technicians would connect the system to the UH-1’s own on-board batteries. General Electric asked the Army for $47,000 to build the prototype.

In addition, General Electric stated it was already working on a plan to shave off a tenth of the weight. At 180 pounds, an experimental M-61 with only three barrels weighed 80 pounds less than the standard model.

A UH-1B armed with an M-139 cannon. U.S. Army photo via Ray Wilhite

The Army was very interested in the gun. It wasn’t so sure about the mount.

After a review of General Electric’s proposal, troops carried out tests of the prototype three-barrel M-61, along with a second, short-barrel version on a special platform in the main cabin. In separate experiments, technicians attached Ford’s M-39 and the Swiss Hispano-Suiza M-139 — both single barrel, 20-millimeter designs — to the same plank.

The heavy guns and their relatively light mounts proved to be a poor combination. When fired, they shook so violently that troops had a hard time hitting their targets.

But the Army wanted the cannon to provide accurate fire on individual targets. Gunship crews already had area-fire weapons — rockets and grenades — to blast dispersed groups of enemy soldiers.

The Army and private companies like General Electric went back to the drawing board. In the meantime, in the mid-1960s, Huey gunships went off to Vietnam with a mix of machine guns, grenade launchers and first-generation wire-guided anti-tank missiles.

Though the Viet Cong guerrillas didn’t have any armored vehicles, crews found the French-designed AGM-22 missiles somewhat useful for blasting bunkers and caves — and they continued to push for a better, more accurate weapon for attacking hardened enemy emplacements.

The Army was also quickly realizing the Huey didn’t make for a good gunship. The choppers were too under-powered to carry all these weapons and still be maneuverable enough to escape incoming fire. Successive engine improvements didn’t help matters much.

Unfortunately, plans for a new, state-of-the-art attack helicopter were moving slowly. Trying to force the Army’s hand, in 1965, Bell had shown off its Model 209 Cobra, the first ever purpose-built helicopter gunship.

The XM-30 armament system showing off its range of motion. U.S. Army photo via Ray Wilhite

By 1968, Army officials had added this new AH-1 to the existing UH-1 gunships in Vietnam. Lockheed continued work on the much more advanced AH-56 Cheyenne.

On top of this, Army engineers and private firms had been steadily working on weapons for all three gunships. Weapons intended for the Cheyenne were nearly ready to go, and no one opposed the idea of strapping them onto the existing UH-1s.

Ford’s 30-millimeter XM-140 seemed like one good option. In development since 1967, engineers at the Army’s Springfield Armory expected the cannon to be one of the main weapons on the AH-56.

The gun fired a special dual-purpose round that could penetrate armor or blow up troops in the open. Technicians proposed attaching one on either side of a Huey gunship.

This XM-30 armament system would be a deadly precision weapon. The gun would sit inside a swiveling pod and the gunner could aim it independently of whichever direction the helicopter was flying.

The Army expected the XM-140 to be a super-weapon that could replace both lighter machine guns and unguided rockets. Problem was — the cannon was a piece of junk.

“Continued problems suspended engineering testing until replacement weapons could be provided in April 1969,” George Chinn wrote in the fifth volume of his definitive The Machine Gun. “Additional modification of the subsystem and weapons delayed the restart of engineering testing until June 1969.”

The Army and Ford went through at least five different sets of prototypes before ultimately scrapping the XM-140 altogether. The cannon never made it to Vietnam.

One of the cannon pods on the much simpler XM-31 system. U.S. Army photo via Ray Wilhite

Instead, Springfield Armory shipped over a small number of much simpler cannon pods. Crews would install the system — the XM-31 — so that one pod sat on either side of the Huey.

Inside each one was an M-24A1 20-millimeter cannon, a derivative of a World War II-era design. Ammunition snaked its way from magazines in the main cabin, up through the roof of the fuselage and then down into the weapons.

It would have been around this time that David proposed his own cannon pack. His undated notes do not say what specific kind of cannon he planned to use on the 188th Company’s Hueys.

By the way, the XM-31 didn’t work out, either. The UH-1 gunships were simply not powerful enough to withstand the shock of firing the big guns and still shoot straight.

In any case, adding more firepower to the Hueys was becoming a moot point. By the early 1970s, as the AH-56 suffered delays, the Army had bought dozens of AH-1 Cobras.

In addition, the new TOW wire-guided missile seemed to point to the end of the gun as a precision weapon on armed choppers. Not everyone agreed, but putting a cannon on a UH-1 was no longer a priority.

In 1969, the U.S. Marine Corps got the first Cobras armed with the production version of General Electric’s three-barrel 20-millimeter cannon. Nearly a decade later, the Army added the same weapon to its AH-1s.

By then, the only American units still flying Huey gunships were in the Army National Guard. Those crews got hand-me-down Vietnam-era weapons kits to go along with the choppers.

The cannon projects — including David’s ideas — were long gone and no one had any time or money to try and start them up again.

The Legend of the Vietnam War’s Mystery Fighter Ace

Joseph Trevithick

Freelance Journalist for @warisboring and others, Historian, and Military Analyst. @franticgoat on Twitter

19 hrs ago

General Electric’s modified M-61 cannon sticks out the side of a UH-1B. U.S. Army photo via Ray Wilhite

The U.S. Army Kept Trying to Give the Huey Bigger Guns

It never worked

by JOSEPH TREVITHICK

A some point during the Vietnam War, a U.S. Army specialist named David drew up a plan to give UH-1 Huey helicopters more firepower. During the conflict, the Hueys relied primarily on 7.62-millimeter machine guns — including fast-firing Miniguns — and unguided rockets.

In his hand-drawn concept, the soldier proposed adding two significantly larger 20-millimeter cannons to a UH-1H troop-carrier. Though the whole system would likely weigh more than 1,200 pounds with a full load of ammunition, technicians would attach it close to the Huey’s center of gravity so as not to throw the chopper off balance.

The setup would have a “solid frame built around [the] helicopter to absorb most of the torque vibration,” the last page in his proposal explained. “The rubber is to absorb high-frequency vibrations.”

We don’t know David’s last name. He wrote it in the corner of all of his diagrams, but it’s illegible in the scanned copy Texas Tech University placed in the online Virtual Vietnam Archive.

The weapon system’s moniker, “XM-188,” isn’t official and was likely a reference to a military unit. The artwork is in a collection of documents related to the 1st Aviation Brigade, which included the 188th Assault Helicopter Company. The setup has no relation whatsoever to the later XM-188 30-millimeter cannon.

We don’t know if David or anyone else in the 188th ever built a working version. What we do know is that the Army had tried repeatedly to give the Huey bigger guns.

It never worked.

David’s XM-188 proposal. U.S. Army art via the Vietnam Center and Archive at Texas Tech University

By the time the Army put its first UH-1s into service in 1959, the notion of armed helicopters had finally started gaining traction. Unfortunately, no one knew what weapons would be suitable or appropriate for the new gunships.

During a series of experiments, Army test crews flew choppers with machine guns, automatic cannon, rockets, guided missiles and more. In 1956, General Electric had cooked up one of the very first helicopter weapon systems from a drawing on a napkin.

In October 1961, the Army went back to the Vermont-based manufacturing giant with a new request — install the 20-millimeter M-61 Vulcan cannon on the Huey. Within two months, the company’s engineers had a put together a detailed plan.

The hard-hitting, six-barrel Gatling gun was already standard armament for U.S. Air Force fighter jets and bombers. The M-61 could also fire several different rounds including high-explosive and incendiary cartridges.

“The M-61 gun is considered by the U.S. Air Force and Army Ordnance as the most reliable machine gun produced,” General Electric bragged in its brochure. War Is Boring found a copy of this document in the National Air and Space Museum Archives.

The firm’s engineers proposed bolting the M-61 high on the left side, in line with the chopper’s center of gravity. An ammunition magazine with 500 rounds in the main cabin would help even out the weight of the 800 pound setup. Since the Vulcan needed electricity to run, technicians would connect the system to the UH-1’s own on-board batteries. General Electric asked the Army for $47,000 to build the prototype.

In addition, General Electric stated it was already working on a plan to shave off a tenth of the weight. At 180 pounds, an experimental M-61 with only three barrels weighed 80 pounds less than the standard model.

A UH-1B armed with an M-139 cannon. U.S. Army photo via Ray Wilhite

The Army was very interested in the gun. It wasn’t so sure about the mount.

After a review of General Electric’s proposal, troops carried out tests of the prototype three-barrel M-61, along with a second, short-barrel version on a special platform in the main cabin. In separate experiments, technicians attached Ford’s M-39 and the Swiss Hispano-Suiza M-139 — both single barrel, 20-millimeter designs — to the same plank.

The heavy guns and their relatively light mounts proved to be a poor combination. When fired, they shook so violently that troops had a hard time hitting their targets.

But the Army wanted the cannon to provide accurate fire on individual targets. Gunship crews already had area-fire weapons — rockets and grenades — to blast dispersed groups of enemy soldiers.

The Army and private companies like General Electric went back to the drawing board. In the meantime, in the mid-1960s, Huey gunships went off to Vietnam with a mix of machine guns, grenade launchers and first-generation wire-guided anti-tank missiles.

Though the Viet Cong guerrillas didn’t have any armored vehicles, crews found the French-designed AGM-22 missiles somewhat useful for blasting bunkers and caves — and they continued to push for a better, more accurate weapon for attacking hardened enemy emplacements.

The Army was also quickly realizing the Huey didn’t make for a good gunship. The choppers were too under-powered to carry all these weapons and still be maneuverable enough to escape incoming fire. Successive engine improvements didn’t help matters much.

Unfortunately, plans for a new, state-of-the-art attack helicopter were moving slowly. Trying to force the Army’s hand, in 1965, Bell had shown off its Model 209 Cobra, the first ever purpose-built helicopter gunship.

The XM-30 armament system showing off its range of motion. U.S. Army photo via Ray Wilhite

By 1968, Army officials had added this new AH-1 to the existing UH-1 gunships in Vietnam. Lockheed continued work on the much more advanced AH-56 Cheyenne.

On top of this, Army engineers and private firms had been steadily working on weapons for all three gunships. Weapons intended for the Cheyenne were nearly ready to go, and no one opposed the idea of strapping them onto the existing UH-1s.

Ford’s 30-millimeter XM-140 seemed like one good option. In development since 1967, engineers at the Army’s Springfield Armory expected the cannon to be one of the main weapons on the AH-56.

The gun fired a special dual-purpose round that could penetrate armor or blow up troops in the open. Technicians proposed attaching one on either side of a Huey gunship.

This XM-30 armament system would be a deadly precision weapon. The gun would sit inside a swiveling pod and the gunner could aim it independently of whichever direction the helicopter was flying.

The Army expected the XM-140 to be a super-weapon that could replace both lighter machine guns and unguided rockets. Problem was — the cannon was a piece of junk.

“Continued problems suspended engineering testing until replacement weapons could be provided in April 1969,” George Chinn wrote in the fifth volume of his definitive The Machine Gun. “Additional modification of the subsystem and weapons delayed the restart of engineering testing until June 1969.”

The Army and Ford went through at least five different sets of prototypes before ultimately scrapping the XM-140 altogether. The cannon never made it to Vietnam.

One of the cannon pods on the much simpler XM-31 system. U.S. Army photo via Ray Wilhite

Instead, Springfield Armory shipped over a small number of much simpler cannon pods. Crews would install the system — the XM-31 — so that one pod sat on either side of the Huey.

Inside each one was an M-24A1 20-millimeter cannon, a derivative of a World War II-era design. Ammunition snaked its way from magazines in the main cabin, up through the roof of the fuselage and then down into the weapons.

It would have been around this time that David proposed his own cannon pack. His undated notes do not say what specific kind of cannon he planned to use on the 188th Company’s Hueys.

By the way, the XM-31 didn’t work out, either. The UH-1 gunships were simply not powerful enough to withstand the shock of firing the big guns and still shoot straight.

In any case, adding more firepower to the Hueys was becoming a moot point. By the early 1970s, as the AH-56 suffered delays, the Army had bought dozens of AH-1 Cobras.

In addition, the new TOW wire-guided missile seemed to point to the end of the gun as a precision weapon on armed choppers. Not everyone agreed, but putting a cannon on a UH-1 was no longer a priority.

In 1969, the U.S. Marine Corps got the first Cobras armed with the production version of General Electric’s three-barrel 20-millimeter cannon. Nearly a decade later, the Army added the same weapon to its AH-1s.

By then, the only American units still flying Huey gunships were in the Army National Guard. Those crews got hand-me-down Vietnam-era weapons kits to go along with the choppers.

The cannon projects — including David’s ideas — were long gone and no one had any time or money to try and start them up again.