Baibars_1260

SENIOR MEMBER

- Joined

- Sep 12, 2020

- Messages

- 2,203

- Reaction score

- 0

- Country

- Location

The Roorkee Internment Camp

The following account is based off a recent interview I had with a 87 year old survivor of the Pakistan Civil War who was interned for two years by the Indian Army from December 1971 to January 1974. To protect the identity of the person certain personal details have been omitted. Some PDF members may have surviving relatives who were interned in the same camp, and thus may be able to identify this person. It is requested that the person's privacy be respected.

1. Tell us about your life immediately before the Civil War?

I was born in the former Indian state then known as the United Provinces in the city of Gorakhpur. I was educated in Lucknow. My husband belonged to Faizabad from the same province.

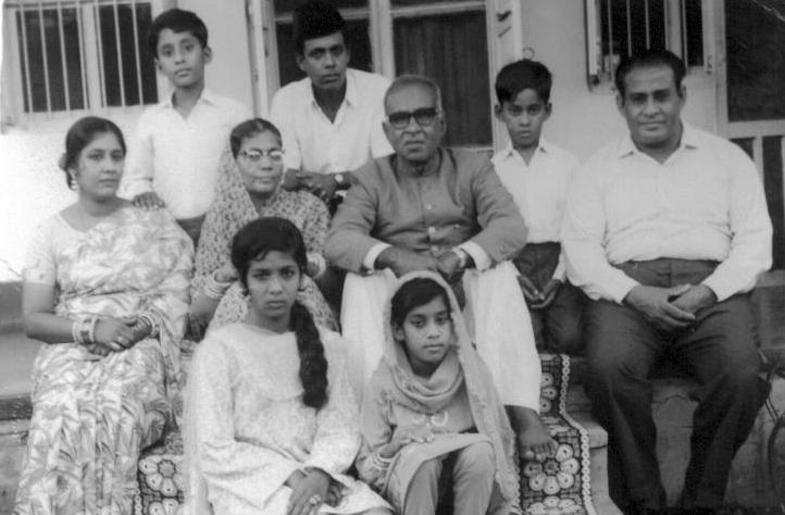

Both our families were prosperous and educated with significant urban and rural properties. Partition violence saw our families divided . My own family stayed in India, though at the time of my marriage in 1952, my husband's entire family had moved to Karachi in West Pakistan.

Shortly after my marriage, my husband and I moved to Dacca, then East Pakistan in late 1952.

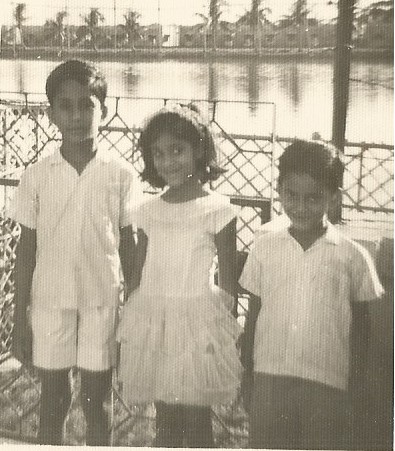

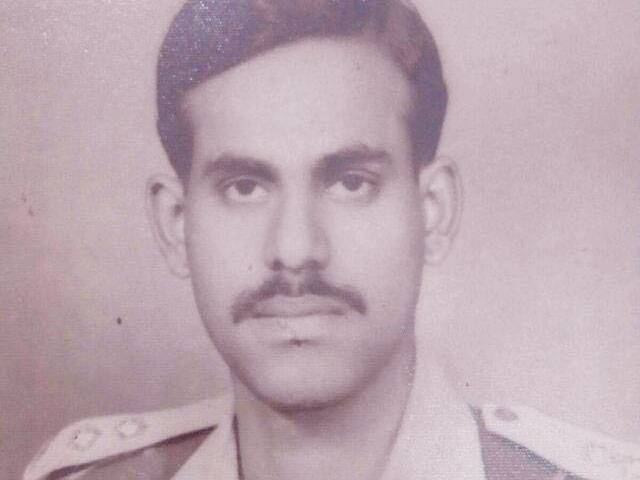

My husband, an engineer by profession set up a business both manufacturing, and dealing in industrial spare parts serving the industries there. We prospered and were living comfortably in the Gulshan area of Dacca in our own home. I had three children.

In early 1971 my eldest daughter had just finished her intermediate science from Dacca University

2. Where were you towards the end of the Civil War and how did you survive the aftermath ?

We were unprepared. My husband was apolitical and he felt that the horrible Civil War would soon be over. As a civilian, and a prominent businessman with substantial business and social contacts within the Bengali community, he didn't feel threatened. We had nothing to do with either armed factions of the civil war. It was only towards mid December 1971, that a friend of ours warned us that our lives were in danger. There was imminent danger of ethnic cleansing. My husband still did not believe we were in danger. Even if India had won the war we would simply be reverting to becoming Indian citizens, or becoming Bangladeshi citizens.

A Pakistani Army truck turned up at our house on 16th December 1971 with a Pakistani officer and a few troops. The officer asked us to leave our home immediately and get into the truck. We were to move to the Cantonment.

"But you have surrendered " my husband said.

"Yes, we have. The Indian Army has asked us to assist in evacuating civilians, and we are retaining our weapons and transport till all endangered civilians can be moved to safety. Please don't waste time and get your family into the truck. "

As we were getting into truck an armed mob rapidly collected outside our house, but were held off by the soldiers who pointed their weapons. As we moved out I looked back, and saw the mob descend on my house and begin looting it.

Further down the road we were stopped by a larger and more heavily armed mob which even our soldiers would not have been able to fend off. We were saved by an Indian Army truck that instantly turned up and began following us. The Indian Army escorted us all the way into the Cantonment area. When we arrived at the cantonment it was packed with civilians and families of Pakistan Armed Forces personnel. There were a few Indian Army personnel present. The Pakistani troops still had their weapons. The Indian Army officers advised us not to leave the premises under any circumstances. Shortly afterwards more Indian troops arrived, and the Pakistani troops surrendered their weapons. We were informed we were officially Prisoners of War. We stayed in the cantonment for a few days until the Indian army told us of their plans for us. Armed forces personnel would be treated as Prisoners of War under the Geneva Convention. As enemy civilians we would be moved temporarily to an internment camp under Indian Army protection and International Red Cross supervision for quick repatriation to Pakistan. There was much confusion as to who exactly was a civilian, and who was an armed forces person as officially the wives and children of the soldiers were also civilians.

We were eventually told that civilians like us who had no connection with the armed forces, would be treated separately, and would be transferred quickly to West Pakistan. We were put in separate trains in batches. A large batch of about 2000 of us were in a train traveling towards Delhi when the train was diverted to the town of Roorkee. We were told that Pakistan had closed the border to traffic, and our repatriation would have to wait till the issue could be sorted out through negotiations. Till that time we would be interned. We arrived in Roorkee towards the fourth week of December 1971. We had no idea then we would be interned for two long years.

3. Were you or your husband able to contact your respective family members ?

No, there was no way for either me or my husband to contact our respective families. My parents and all my brothers and sisters were in India, and my husbands parents, and siblings were in West Pakistan. Because our whereabouts were not known we were presumed dead by both our families.

4. So what happened when you arrived at Roorkee?

It was a large camp, one of the many that India has set up to imprison almost 100,000 of its enemy civilians. The Roorkee camp was one of the larger camps was probably an army barrack, or a government worker's housing establishment of some kind that had been converted as an internment camp. It was very spread out over 20 to 30 acres , with a number of separate single story buildings in rows, called "halls".

The camp was fenced in with double rows of barbed wire fencing with one outer and one inner entry gate. There was a commandant's office outside.

This was a civilian camp for upper and upper middle class internees who were from diverse backgrounds. There were doctors, engineers, teachers, bankers, police officers, merchant marine officers, private sector individuals from tea garden managers, to export import business houses, insurance, employees of foreign airlines. There were a small number of government officials, and civil service officials as well.

5.Were there any injured or sick amongst you ?

Yes, some were injured, and the last we saw of them after we got off the train was being whisked away in an army ambulance to a hospital.

6.So how did the Indian Army organize the camp ?

Only the unmarried men were separated and housed separately. The families with the parents and children were kept together in separate halls. Single unmarried or widowed women, shared a hall with a family.

We were two to three families to a "hall", but since the rooms were large and airy we didn't feel cramped. We were provided beds and blankets. It was very cold there. There were separate washing and toilet facilities.

The "halls" and inner area were strictly out of bounds to Indian Army personnel, who only patrolled the outer perimeter. There was a Colonel who was the camp commandant who turned up every morning and evening to enquire if there were any complaints. This was not an armed forces camp, so the Indians were not worried about us attempting to escape, nor did they feel threatened by us. We had nowhere to go..

7. What about your food and clothes...?

At first the food was frugal and monotonous, but still adequate . Every morning there was tea and two puris with some sort of bhaji given to each person in the morning. Children under 12 years were provided half liter of milk. The day meal and night meal was the same basically a little daal, a vegetable curry and roti . The food was strictly vegetarian.

We had no clothes other than what we had been wearing when we left and these deteriorated rapidly.

8. So it was like this for two years...?

No, after the first month the Indians asked us to organize ourselves and informed us that we were not going home soon. So we literally set up a whole colony.

We had our own kitchen, our own tailoring shop to repair our clothes and our own school, our own clinic.

The doctors amongst us were supported by hastily trained female members of our camp who delivered babies ( yes, a few of our female camp members were pregnant when we got interned.). The Indian Army and International Red Cross provided basic medical supplies, and basic educational material for children. Food was brought in to our kitchen and we prepared the food ourselves in a langar style. There were engineers amongst us including my husband, who took up the maintenance work of the utilities whenever there was a breakdown repairing the systems themselves. The Indians provided tools and spares. Basically the Indians left us to ourselves for the first 6 months. But things began to change...

9. Were there any deaths in the camp...?

Yes, of course, very frequently. Women died in childbirth, others sickened and died , some died of natural causes. Roorkee had an Indian Muslim population nearby in a village with a graveyard. When someone died the Indian Army would requisition the bier ( taboot) from the village and drag the imam over to perform the namaz e janaza and carry off the body in a truck .. A few immediate relatives if available were allowed to accompany the body to the graveyard for burial, but sometimes it was a single person and the Indian Army would simply ask the villagers to perform the last rites.

10. How did your situation change.

( To be continued...)

The following account is based off a recent interview I had with a 87 year old survivor of the Pakistan Civil War who was interned for two years by the Indian Army from December 1971 to January 1974. To protect the identity of the person certain personal details have been omitted. Some PDF members may have surviving relatives who were interned in the same camp, and thus may be able to identify this person. It is requested that the person's privacy be respected.

1. Tell us about your life immediately before the Civil War?

I was born in the former Indian state then known as the United Provinces in the city of Gorakhpur. I was educated in Lucknow. My husband belonged to Faizabad from the same province.

Both our families were prosperous and educated with significant urban and rural properties. Partition violence saw our families divided . My own family stayed in India, though at the time of my marriage in 1952, my husband's entire family had moved to Karachi in West Pakistan.

Shortly after my marriage, my husband and I moved to Dacca, then East Pakistan in late 1952.

My husband, an engineer by profession set up a business both manufacturing, and dealing in industrial spare parts serving the industries there. We prospered and were living comfortably in the Gulshan area of Dacca in our own home. I had three children.

In early 1971 my eldest daughter had just finished her intermediate science from Dacca University

2. Where were you towards the end of the Civil War and how did you survive the aftermath ?

We were unprepared. My husband was apolitical and he felt that the horrible Civil War would soon be over. As a civilian, and a prominent businessman with substantial business and social contacts within the Bengali community, he didn't feel threatened. We had nothing to do with either armed factions of the civil war. It was only towards mid December 1971, that a friend of ours warned us that our lives were in danger. There was imminent danger of ethnic cleansing. My husband still did not believe we were in danger. Even if India had won the war we would simply be reverting to becoming Indian citizens, or becoming Bangladeshi citizens.

A Pakistani Army truck turned up at our house on 16th December 1971 with a Pakistani officer and a few troops. The officer asked us to leave our home immediately and get into the truck. We were to move to the Cantonment.

"But you have surrendered " my husband said.

"Yes, we have. The Indian Army has asked us to assist in evacuating civilians, and we are retaining our weapons and transport till all endangered civilians can be moved to safety. Please don't waste time and get your family into the truck. "

As we were getting into truck an armed mob rapidly collected outside our house, but were held off by the soldiers who pointed their weapons. As we moved out I looked back, and saw the mob descend on my house and begin looting it.

Further down the road we were stopped by a larger and more heavily armed mob which even our soldiers would not have been able to fend off. We were saved by an Indian Army truck that instantly turned up and began following us. The Indian Army escorted us all the way into the Cantonment area. When we arrived at the cantonment it was packed with civilians and families of Pakistan Armed Forces personnel. There were a few Indian Army personnel present. The Pakistani troops still had their weapons. The Indian Army officers advised us not to leave the premises under any circumstances. Shortly afterwards more Indian troops arrived, and the Pakistani troops surrendered their weapons. We were informed we were officially Prisoners of War. We stayed in the cantonment for a few days until the Indian army told us of their plans for us. Armed forces personnel would be treated as Prisoners of War under the Geneva Convention. As enemy civilians we would be moved temporarily to an internment camp under Indian Army protection and International Red Cross supervision for quick repatriation to Pakistan. There was much confusion as to who exactly was a civilian, and who was an armed forces person as officially the wives and children of the soldiers were also civilians.

We were eventually told that civilians like us who had no connection with the armed forces, would be treated separately, and would be transferred quickly to West Pakistan. We were put in separate trains in batches. A large batch of about 2000 of us were in a train traveling towards Delhi when the train was diverted to the town of Roorkee. We were told that Pakistan had closed the border to traffic, and our repatriation would have to wait till the issue could be sorted out through negotiations. Till that time we would be interned. We arrived in Roorkee towards the fourth week of December 1971. We had no idea then we would be interned for two long years.

3. Were you or your husband able to contact your respective family members ?

No, there was no way for either me or my husband to contact our respective families. My parents and all my brothers and sisters were in India, and my husbands parents, and siblings were in West Pakistan. Because our whereabouts were not known we were presumed dead by both our families.

4. So what happened when you arrived at Roorkee?

It was a large camp, one of the many that India has set up to imprison almost 100,000 of its enemy civilians. The Roorkee camp was one of the larger camps was probably an army barrack, or a government worker's housing establishment of some kind that had been converted as an internment camp. It was very spread out over 20 to 30 acres , with a number of separate single story buildings in rows, called "halls".

The camp was fenced in with double rows of barbed wire fencing with one outer and one inner entry gate. There was a commandant's office outside.

This was a civilian camp for upper and upper middle class internees who were from diverse backgrounds. There were doctors, engineers, teachers, bankers, police officers, merchant marine officers, private sector individuals from tea garden managers, to export import business houses, insurance, employees of foreign airlines. There were a small number of government officials, and civil service officials as well.

5.Were there any injured or sick amongst you ?

Yes, some were injured, and the last we saw of them after we got off the train was being whisked away in an army ambulance to a hospital.

6.So how did the Indian Army organize the camp ?

Only the unmarried men were separated and housed separately. The families with the parents and children were kept together in separate halls. Single unmarried or widowed women, shared a hall with a family.

We were two to three families to a "hall", but since the rooms were large and airy we didn't feel cramped. We were provided beds and blankets. It was very cold there. There were separate washing and toilet facilities.

The "halls" and inner area were strictly out of bounds to Indian Army personnel, who only patrolled the outer perimeter. There was a Colonel who was the camp commandant who turned up every morning and evening to enquire if there were any complaints. This was not an armed forces camp, so the Indians were not worried about us attempting to escape, nor did they feel threatened by us. We had nowhere to go..

7. What about your food and clothes...?

At first the food was frugal and monotonous, but still adequate . Every morning there was tea and two puris with some sort of bhaji given to each person in the morning. Children under 12 years were provided half liter of milk. The day meal and night meal was the same basically a little daal, a vegetable curry and roti . The food was strictly vegetarian.

We had no clothes other than what we had been wearing when we left and these deteriorated rapidly.

8. So it was like this for two years...?

No, after the first month the Indians asked us to organize ourselves and informed us that we were not going home soon. So we literally set up a whole colony.

We had our own kitchen, our own tailoring shop to repair our clothes and our own school, our own clinic.

The doctors amongst us were supported by hastily trained female members of our camp who delivered babies ( yes, a few of our female camp members were pregnant when we got interned.). The Indian Army and International Red Cross provided basic medical supplies, and basic educational material for children. Food was brought in to our kitchen and we prepared the food ourselves in a langar style. There were engineers amongst us including my husband, who took up the maintenance work of the utilities whenever there was a breakdown repairing the systems themselves. The Indians provided tools and spares. Basically the Indians left us to ourselves for the first 6 months. But things began to change...

9. Were there any deaths in the camp...?

Yes, of course, very frequently. Women died in childbirth, others sickened and died , some died of natural causes. Roorkee had an Indian Muslim population nearby in a village with a graveyard. When someone died the Indian Army would requisition the bier ( taboot) from the village and drag the imam over to perform the namaz e janaza and carry off the body in a truck .. A few immediate relatives if available were allowed to accompany the body to the graveyard for burial, but sometimes it was a single person and the Indian Army would simply ask the villagers to perform the last rites.

10. How did your situation change.

( To be continued...)

Last edited: