RescueRanger

PDF THINK TANK: CONSULTANT

- Joined

- Sep 20, 2008

- Messages

- 16,370

- Reaction score

- 244

- Country

- Location

Opinion | National Security | Emergency Management:

Disaster risk reduction and management have become key concepts in present-day development practices across the world. Globally and regionally, we are experiencing a constant increase in socioeconomic losses due to disasters.

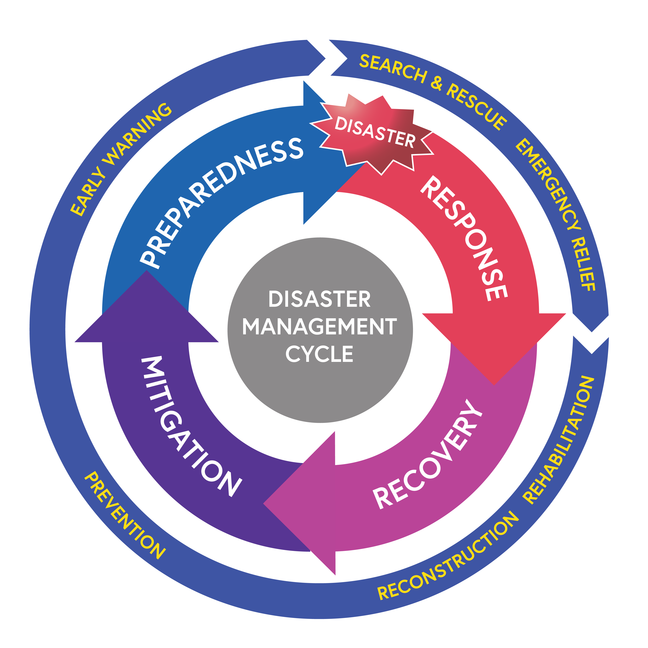

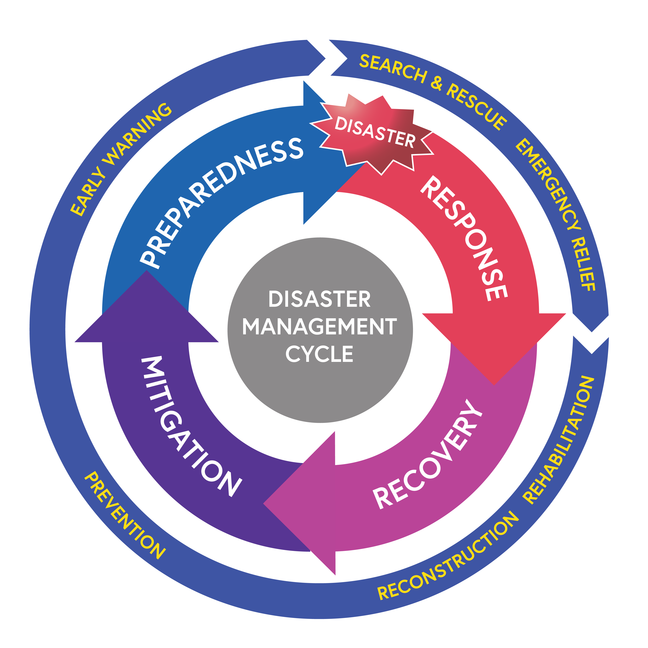

Figure 1: Disaster Management Cycle

Figure 2: Pakistan's disaster management framework

Geological, ecological and climatic changes are persistently mounting disaster threats for the world community in general and developing nations. With Little or no warning, disasters and emergencies can happen. The local government’s ability to respond to these incidents can be quickly overwhelmed.

We have all had the misfortune to witness or be directly impacted by an emergency in our lives. It is in times such as this, be it the roadside accident or a major national emergency such as the October 2005 earthquake in Kashmir, Pakistan that we see the human nature truly shine.

It is in times of hardship, struggle and strife the desire to help others often becomes overwhelming. Coupled with uncertainty, anxiousness and the innate drive to help, people are driven to converge on the scene and attempt to render assistance in any way possible.

However, alongside official first responders, such incidents not only draw the well-intentioned volunteer, but also play host to a flurry of other actors, the press and onlookers.

The Journal of Emergency Management explains that while there is little to no conclusive socio-demographic evidence available to explain what drives certain people to volunteer spontaneously, it does elaborate that convergence in the context of disasters is partly driven by people who have previously been affected by a similar incident. Constant media attention can also apparently drive people to take action.

This can be witnessed time and time again on TV when entire bands of well-intentioned people come together to try and help at the site of an accident or emergency.

However, these untrained and highly charged individuals, with little or no supervision, often place themselves and others in perilous positions. The lack of training and organisation can further compound the problem and may even lead to complications such as further injuries, deaths or the contamination of vital evidence on site.[4]

An example of well-intenetioned volunteers coming to help but becoming casualties themselves due to lack of training, preparedness and appropriate equipment.

Therefore it is imperative for emergency managers and first responders to understand convergence behaviour in the context of disaster response. Fritz and Mathewson categorised five types of people who converge on a disaster scene:

1. Helpers: formal and informal attempting to provide assistance

2. Returnees: residents or those people who initially evacuated the area

3. Anxious: family and friends seeking information about loved ones

4. Curious: onlookers attempting to view the impacted area

5. Exploiters: seeking to take advantage of the circumstances

Faced with a mix of emotions, personalities and demands of the actual response, the emergency services can quickly become overwhelmed and scene management can be compromised.[5]

That is not to say that spontaneous volunteers are not a force for good, on the contrary, according to International Disaster Nursing: “Informal helpers may help because of their proximity to the site, knowledge of the area/victims, the ability to function outside the bureaucratic mechanism or being able to provide vital skills when a gap in the response capacity exists.”[1]

Such actions have been witnessed the world over, stories of how people banded together to help others. However, at the same time, complex emergencies and large scale uncontrolled volunteering can create a situation where unscrupulous elements can exploit the chaos. As a first responder I have seen this on more occasions than I care to remember.

For example, when working as a rescuer at the Margalla Towers in 2005, we had to abandon rescue operations for a short period and I injured my hand badly as I pulled a Japanese photographer out of harm’s way as he was almost crushed under the stampede of people after an onlooker had started a rumour that the surrounding buildings were collapsing.

In addition to managing the press, scene safety, incident response, personnel management, logistics and the inevitable bureaucracy, emergency managers and responders also face the difficult decision to ‘vet’ and manage the risks posed by non-responders on scene.

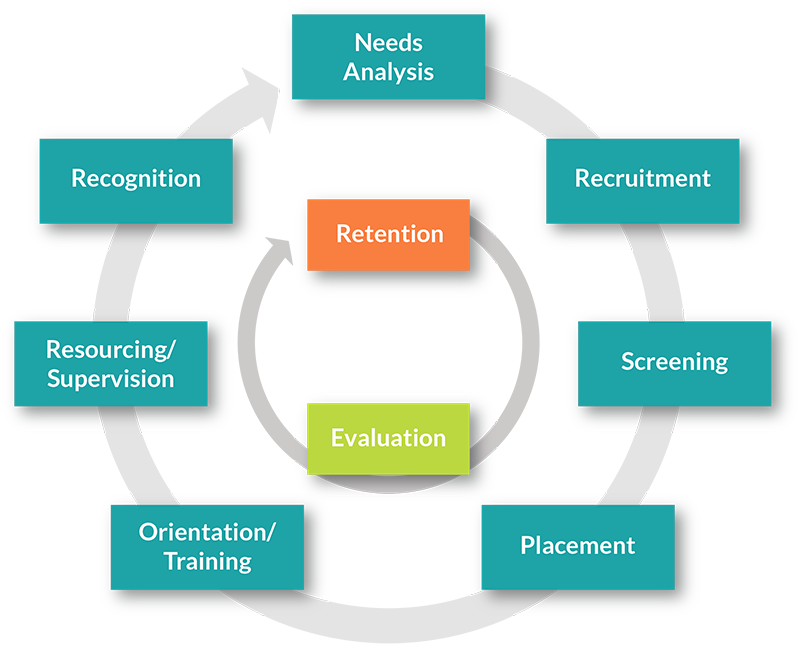

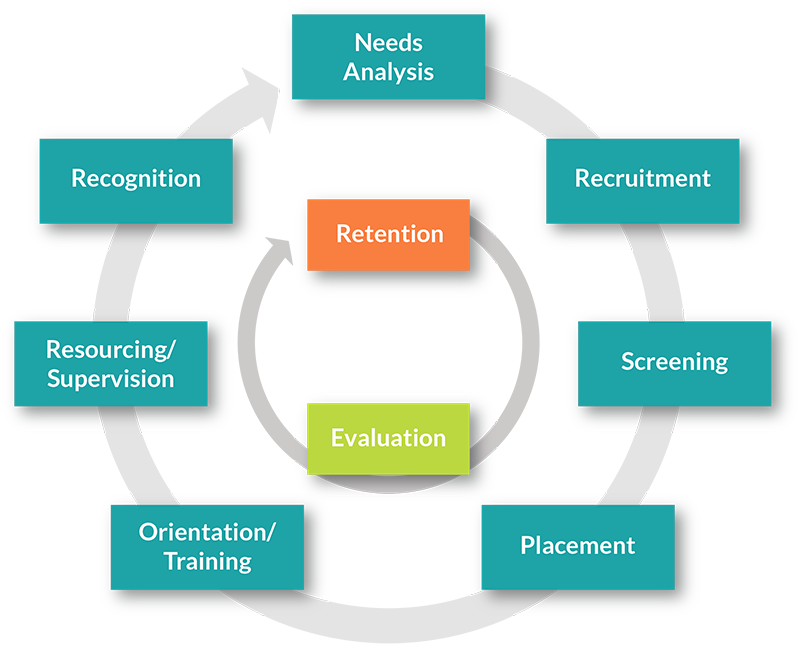

Figure 3: The volunteer management cycle

Pakistan is not an isolated case; it is because of similar problems that the United States Department of Homeland Security and Federal Emergency Management Agency created and polished the Incident Command System and National Incident Management System.

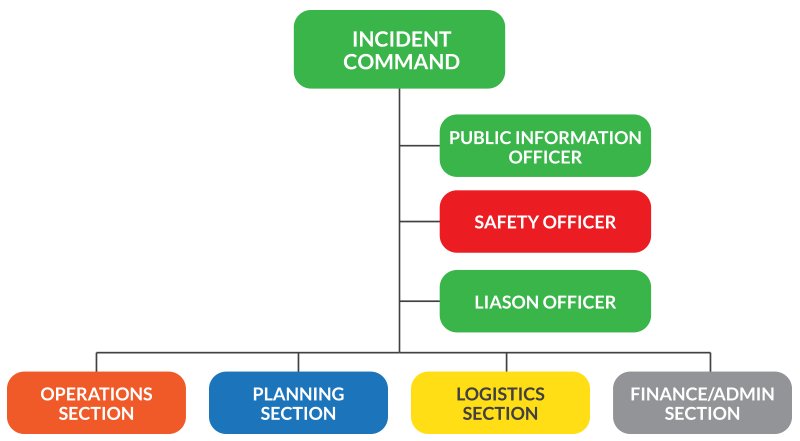

Figure 4: A Basic Incident Command System

The benefits of a unified and modular incident command system are that it empowers professional responders such as the police, rescue and military rapidly have to take control of scene safety, prioritise response, assess damage and evaluate needs and control the information collected and disseminated, ensuring accountability all the while.[2]

In addition to the ICS the government should work in partnership with other key players such as civil society and the media during such incidents, using such valuable resource as an extension of the response and not a hindrance to it.

Figure 5: Perimeter controls during a large scale emergency or disaster

Similarly, non-government actors, the media and volunteers should respect the stresses placed on government services during response to mass casualty incidents and large-scale emergencies and respect the cordon.[3]

Pakistan has come a long way since 2005, we now have specialist rescue teams and a respectable emergency medical service in the form of Rescue 1122 that is quickly expanding to parts of the country. However, until a unified incident command system is designed and implemented, we will continue to see more missed opportunities and unnecessary losses.

Investing in a modular incident command system that is adaptive to local needs and incorporates the need to engage with community volunteers will empower responders, promote citizenship, improve accountability, ensure control over information flow and ultimately strengthen national resilience.

References:

[1] Disaster and Terrorism Editorial - Convergence Behaviour in Disasters; Ann Emergency Medicine 2003

[2] UN INSARAG Guidelines 2015

[3] United Nations Disaster Assessment and Coordination Field Handbook, 7th Edition (2018)

[4] Disaster Study Number 9, Convergence Behaviour in Disasters : A Problem in Social Control, CHARLES E. FRITZ AND J. H. MATHEWSON, Committee on Disaster Studies, National Academy off Sciences-National Research Council, Publication 476

@Slav Defence @WebMaster @Horus @WAJsal @Irfan Baloch @Foxtrot Alpha

Disaster risk reduction and management have become key concepts in present-day development practices across the world. Globally and regionally, we are experiencing a constant increase in socioeconomic losses due to disasters.

Figure 1: Disaster Management Cycle

Figure 2: Pakistan's disaster management framework

Geological, ecological and climatic changes are persistently mounting disaster threats for the world community in general and developing nations. With Little or no warning, disasters and emergencies can happen. The local government’s ability to respond to these incidents can be quickly overwhelmed.

We have all had the misfortune to witness or be directly impacted by an emergency in our lives. It is in times such as this, be it the roadside accident or a major national emergency such as the October 2005 earthquake in Kashmir, Pakistan that we see the human nature truly shine.

It is in times of hardship, struggle and strife the desire to help others often becomes overwhelming. Coupled with uncertainty, anxiousness and the innate drive to help, people are driven to converge on the scene and attempt to render assistance in any way possible.

However, alongside official first responders, such incidents not only draw the well-intentioned volunteer, but also play host to a flurry of other actors, the press and onlookers.

The Journal of Emergency Management explains that while there is little to no conclusive socio-demographic evidence available to explain what drives certain people to volunteer spontaneously, it does elaborate that convergence in the context of disasters is partly driven by people who have previously been affected by a similar incident. Constant media attention can also apparently drive people to take action.

This can be witnessed time and time again on TV when entire bands of well-intentioned people come together to try and help at the site of an accident or emergency.

However, these untrained and highly charged individuals, with little or no supervision, often place themselves and others in perilous positions. The lack of training and organisation can further compound the problem and may even lead to complications such as further injuries, deaths or the contamination of vital evidence on site.[4]

Therefore it is imperative for emergency managers and first responders to understand convergence behaviour in the context of disaster response. Fritz and Mathewson categorised five types of people who converge on a disaster scene:

1. Helpers: formal and informal attempting to provide assistance

2. Returnees: residents or those people who initially evacuated the area

3. Anxious: family and friends seeking information about loved ones

4. Curious: onlookers attempting to view the impacted area

5. Exploiters: seeking to take advantage of the circumstances

Faced with a mix of emotions, personalities and demands of the actual response, the emergency services can quickly become overwhelmed and scene management can be compromised.[5]

That is not to say that spontaneous volunteers are not a force for good, on the contrary, according to International Disaster Nursing: “Informal helpers may help because of their proximity to the site, knowledge of the area/victims, the ability to function outside the bureaucratic mechanism or being able to provide vital skills when a gap in the response capacity exists.”[1]

Such actions have been witnessed the world over, stories of how people banded together to help others. However, at the same time, complex emergencies and large scale uncontrolled volunteering can create a situation where unscrupulous elements can exploit the chaos. As a first responder I have seen this on more occasions than I care to remember.

For example, when working as a rescuer at the Margalla Towers in 2005, we had to abandon rescue operations for a short period and I injured my hand badly as I pulled a Japanese photographer out of harm’s way as he was almost crushed under the stampede of people after an onlooker had started a rumour that the surrounding buildings were collapsing.

In addition to managing the press, scene safety, incident response, personnel management, logistics and the inevitable bureaucracy, emergency managers and responders also face the difficult decision to ‘vet’ and manage the risks posed by non-responders on scene.

Figure 3: The volunteer management cycle

Pakistan is not an isolated case; it is because of similar problems that the United States Department of Homeland Security and Federal Emergency Management Agency created and polished the Incident Command System and National Incident Management System.

Figure 4: A Basic Incident Command System

The benefits of a unified and modular incident command system are that it empowers professional responders such as the police, rescue and military rapidly have to take control of scene safety, prioritise response, assess damage and evaluate needs and control the information collected and disseminated, ensuring accountability all the while.[2]

In addition to the ICS the government should work in partnership with other key players such as civil society and the media during such incidents, using such valuable resource as an extension of the response and not a hindrance to it.

Figure 5: Perimeter controls during a large scale emergency or disaster

Similarly, non-government actors, the media and volunteers should respect the stresses placed on government services during response to mass casualty incidents and large-scale emergencies and respect the cordon.[3]

Pakistan has come a long way since 2005, we now have specialist rescue teams and a respectable emergency medical service in the form of Rescue 1122 that is quickly expanding to parts of the country. However, until a unified incident command system is designed and implemented, we will continue to see more missed opportunities and unnecessary losses.

Investing in a modular incident command system that is adaptive to local needs and incorporates the need to engage with community volunteers will empower responders, promote citizenship, improve accountability, ensure control over information flow and ultimately strengthen national resilience.

References:

[1] Disaster and Terrorism Editorial - Convergence Behaviour in Disasters; Ann Emergency Medicine 2003

[2] UN INSARAG Guidelines 2015

[3] United Nations Disaster Assessment and Coordination Field Handbook, 7th Edition (2018)

[4] Disaster Study Number 9, Convergence Behaviour in Disasters : A Problem in Social Control, CHARLES E. FRITZ AND J. H. MATHEWSON, Committee on Disaster Studies, National Academy off Sciences-National Research Council, Publication 476

@Slav Defence @WebMaster @Horus @WAJsal @Irfan Baloch @Foxtrot Alpha