Hamartia Antidote

ELITE MEMBER

- Joined

- Nov 17, 2013

- Messages

- 35,188

- Reaction score

- 30

- Country

- Location

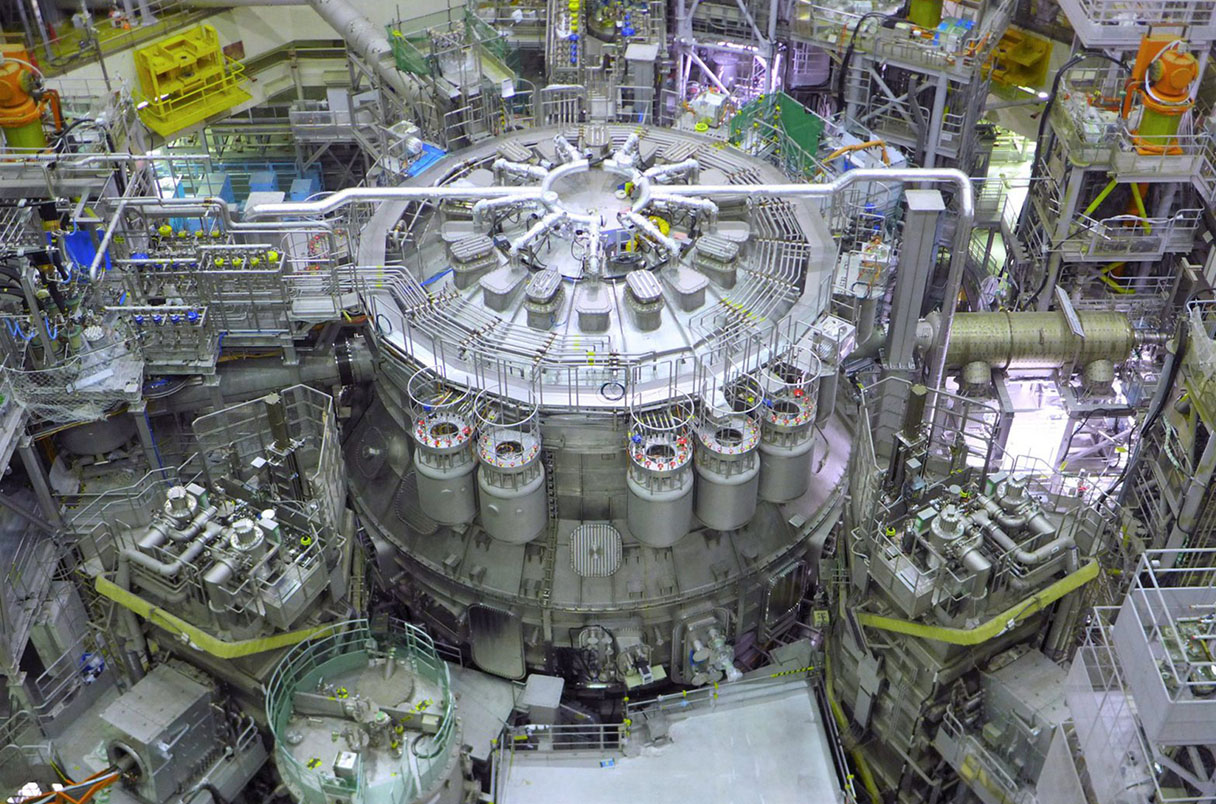

The long trek toward practical fusion energy passed a milestone last week when the world’s newest and largest fusion reactor fired up. Japan’s JT-60SA uses magnetic fields from superconducting coils to contain a blazingly hot cloud of ionized gas, or plasma, within a doughnut-shaped vacuum vessel, in hope of coaxing hydrogen nuclei to fuse and release energy. The four-story-high machine is designed to hold a plasma heated to 200 million degrees Celsius for about 100 seconds, far longer than previous large tokamaks.

Last week’s achievement “proves to the world that the machine fulfills its basic function,” says Sam Davis, a project manager at Fusion for Energy, an EU organization working with Japan’s National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology (QST) on JT-60SA and related programs. It will take another 2 years before JT-60SA produces the long-lasting plasmas needed for meaningful physics experiments, says Hiroshi Shirai, leader of the project for QST.

JT-60SA will also help ITER, the mammoth international fusion reactor under construction in France that’s intended to demonstrate how fusion can generate more energy than goes into producing it. ITER will rely on technologies and operating know-how that JT-60SA will test.

The long trek toward practical fusion energy passed a milestone last week when the world’s newest and largest fusion reactor fired up. Japan’s JT-60SA uses magnetic fields from superconducting coils to contain a blazingly hot cloud of ionized gas, or plasma, within a doughnut-shaped vacuum vessel, in hope of coaxing hydrogen nuclei to fuse and release energy. The four-story-high machine is designed to hold a plasma heated to 200 million degrees Celsius for about 100 seconds, far longer than previous large tokamaks.

Last week’s achievement “proves to the world that the machine fulfills its basic function,” says Sam Davis, a project manager at Fusion for Energy, an EU organization working with Japan’s National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology (QST) on JT-60SA and related programs. It will take another 2 years before JT-60SA produces the long-lasting plasmas needed for meaningful physics experiments, says Hiroshi Shirai, leader of the project for QST.

JT-60SA will also help ITER, the mammoth international fusion reactor under construction in France that’s intended to demonstrate how fusion can generate more energy than goes into producing it. ITER will rely on technologies and operating know-how that JT-60SA will test.

One limitation is that JT-60SA will only use hydrogen and its isotope deuterium in its experiments, not tritium—a third form of hydrogen that is expensive, scarce, and radioactive. Tritium is considered the most efficient option for energy production, so ITER plans to begin using deuterium-tritium fuel in 2035.

By 2050, Japan also hopes to build DEMO, a proposed demonstration power plant that would provide a stepping stone from the research of JT-60SA and ITER to commercial fusion power. Shirai says he is well aware of the competition from alternative approaches to fusion energy, fueled by an influx of private money into the field. But with competition comes opportunities for collaborations among those with new ideas. “Having many people coming into this area is a very good thing,” Shirai says.