Naif al Hilali

FULL MEMBER

- Joined

- Nov 5, 2016

- Messages

- 324

- Reaction score

- 24

- Country

- Location

War Is Boring

We go to war so you don’t have to

May 15

Bex Walton/Flickr photo

A Missing Piece of Obama’s Terrorist ‘Kill Memo’ Still Haunts America

The lack of adversarial opinion for a 2011 drone strike on Anwar Al Awlaki could presage the killing of U.S. citizens in America

by JAMES PERRY STEVENSON

When U.S. Pres. Barack Obama considered the unprecedented step of intentionally killing an American citizen without judicial process, he asked for a legal opinion that would provide legal cover in case he was accused of a war crime.

Unfortunately, he did not ask for two opinions, one providing authority for killing a citizen and the other why it would be illegal, or at least we have no evidence for an opposing legal position. His request raises an interesting question — under what circumstances is it legal to kill an American citizen without due process?

Virtually all jurisdictions define “murder” as the “unlawful killing of a human being.” The operative word here is “unlawful.” If someone goes into a building on a shooting spree, no time exists for a warrant, a hearing or a trial.

Killing someone on a shooting spree would be a lawful killing because no time exists for a constitutionally-mandated legal process. Under these conditions, killing the shooter, regardless of his or her citizenship, is legal.

Obama’s request was for a similar legal justification. In this case, that killing radical preacher Anwar Al Awlaki would be a lawful killing. Then Attorney General Eric Holder supplied the 97-page legal memorandum, generated 14 months prior to the successful September 2011 assassination of Awlaki, who the U.S. government accused of being a key figure in Al Qaeda’s recruitment efforts.

The legal memorandum was designed to satisfy the president that killing Awlaki without a trial, without judicial process, and with the only “due process” coming from a handful of bureaucrats from the executive branch, would make it legal. In the process, Obama violated one of the fundamental premises in the Anglo-American legal system, one honed by centuries of precedent — the belief that through adversarial proceedings, the truth will emerge.

Obama did not ask for a rebuttal memorandum (or if he did, he never shared it), one offering countervailing considerations and containing opposing points of view — a memorandum that would indicate he had been fully briefed from all perspectives, an opinion that might have made him reach a different conclusion.

Since Obama appears to have asked for only one point of view, he did not have the benefit of hearing a contrarian legal perspective. So here is a non-lawyer’s attempt to show why he should not have killed Awlaki.

An MQ-1B Predator drone. U.S. Air Force photo

Imminent threat

First of all, if Obama had received an opinion representing Awlaki’s legal interests, he would have read that an international legal test for “imminent threat,” known as the Caroline Test, states that the threat must be “instant, overwhelming, and leaving no choice of means, and no moment for deliberation.”

“Imminent” used as an adjective modifying “threat” has also been defined by courts as “immediate danger, such as must be instantly met, such as cannot be guarded against by calling for the assistance of others or the protection of the law.”

Similar legal reasoning comes from a North Carolina Supreme Court case: “The right to kill in self-defense is based on the necessity, real or reasonably apparent, of killing an unlawful aggressor to save oneself from imminent death or great bodily harm at his hands.”

The legal memorandum Holder provided to Obama relies on the dubious and questionable legal argument that Awlaki was an “imminent threat.” The irony here is that if Awlaki were actually an “imminent threat,” no memorandum would have been necessary because anyone has the right to kill someone for killing unlawfully.

Buy ‘Objective Troy: A Terrorist, a President, and the Rise of the Drone’

But in an attempt to show that Awlaki was worse than an “imminent” threat, the legal memorandum defined him as a “continued imminent threat.” On the contrary, the only thing that “continued” was the government’s position that it could not capture Awlaki, a requirement it had under the Laws of Armed Conflict.

The government’s assertion that capturing Awlaki was not feasible strains credulity. To believe that SEAL Team Six could not have captured Awlaki, roaming the Yemeni desert, surrounded by a few friends and nothing else but hundreds of square miles of sand, is to ignore the more difficult captures by SEAL teams, such as the successful rescue of Richard Phillips bobbing in the Indian Ocean.

To be sure, there are times when government officials need to react quickly and order the killing of other human beings, without judicial or due process, but these kinds of exigencies were not present with Awlaki. The government chased Awlaki for over a year in an attempt to kill him, proving that as a threat he was far from imminent.

The Caroline Test provides a valid definition for the phrase “imminent threat,” a definition created by Secretary of State Daniel Webster in the 1830s, reaffirmed by the Nuremberg Tribunal in the late 1940s, and defined by the Supreme Court of North Carolina as “immediate danger, such as must be instantly met, such as cannot be guarded against by calling for the assistance of others or the protection of the law.”

Due process

When Awlaki was killed in September 2011, Holder was criticized his failure to provide Awlaki “due process,” a constitutional guarantee embedded in the Fifth Amendment. In response, Holder said that the Constitution promises due process but not judicial process.

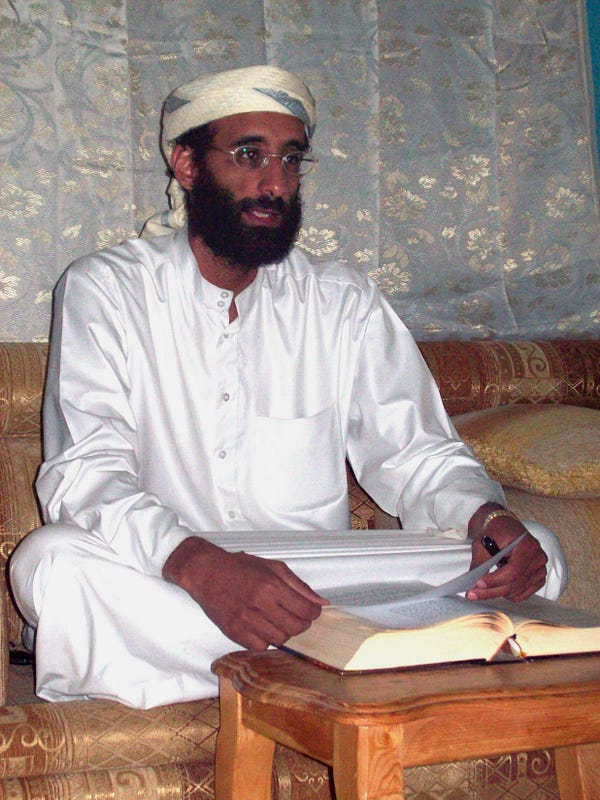

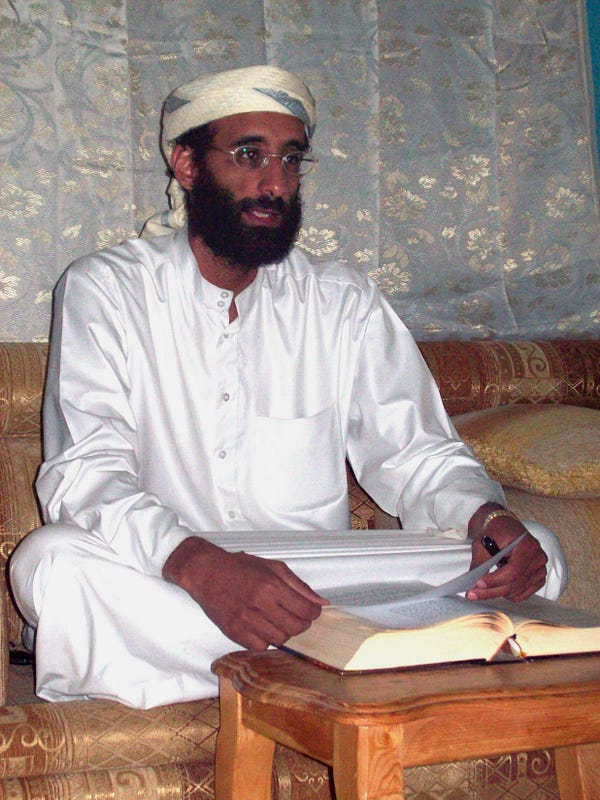

Anwar Al Awlaki in Yemen in 2008. Muhammad ud-Deen/Wikimedia photo

The Department of Justice justified killing Awlaki without judicial process by citing the Supreme Court decision Mathews v. Eldridge, as though the Mathews decision stood for the principle that administrative hearings could replace judicial ones.

On the contrary, the Mathews case was about how much due process one is entitled to in administrative hearings on disability benefits. However, the Mathews case made it unambiguous that the greater the potential loss of rights, the greater the requirement for judicial as opposed to executive branch due process.

Amplifying the Mathews language, the Supreme Court wrote in Hamdi v. Rumsfeld — which dealt with the rights of detainees — that “procedural due process rules are meant to protect persons not from the deprivation, but from the mistaken or unjustified deprivation of life, liberty, or property.”

Moreover, the Hamdi case emphasized “the right to procedural due process is ‘absolute’ in the sense that it does not depend upon the merits of a claimant’s substantive assertions.”

Even in cases involving enemy combatants, in which the military wanted to shortcut the Constitution, the Supreme Court insisted “that a citizen-detainee seeking to challenge his classification as an enemy combatant must receive notice of the factual basis for his classification, and a fair opportunity to rebut the government’s factual assertions before a neutral decision maker.”

Noting the irony in the government’s argument, the Supreme Court wrote in United States v. Robel, “t would indeed be ironic if, in the name of national defense, we would sanction the subversion of one of those liberties … which makes the defense of the nation worthwhile.”

In spite of the executive branch’s attempt to minimize the role of the federal judiciary in wartime, the Hamdi court rejected the idea that war is an excuse to reduce due process to the equivalent of an administrative hearing:

Indeed, the position that the courts must forgo any examination of the individual case and focus exclusively on the legality of the broader detention scheme cannot be mandated by any reasonable view of separation of powers, as this approach serves only to condense power into a single branch of government. We have long since made clear that a state of war is not a blank check for the president when it comes to the rights of the nation’s citizens.

This leads us to ask — if the Supreme Court has taken the position that a detained citizen has a right to “rebut the government’s factual assertions before a neutral decision maker,” wouldn’t it provide these same or greater safeguards for an American citizen, scheduled to be killed, particularly when he does not fit the definition of an imminent threat?

Most likely yes, but the White House says otherwise

The legal memorandum the Department of Justice delivered to the president takes the position that the Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF), passed by Congress within days after Sept. 11, 2001, authorized the killing of Awlaki and suspended his Fifth Amendment rights under the U.S. Constitution.

The AUMF states:

The president is authorized to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons, in order to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States by such nations, organizations or persons.

But note that the AUMF emphasizes actions accused terrorists took in the past. Since Awlaki was not involved with any adversarial proceedings against the United States in the past, the AUMF does not apply to him personally. To the degree that he later became an adversary, his evolved status could and should be addressed without reliance on the AUMF.

Since the AUMF statute is brief enough, we can easily parse out its phrases in a search for relevancy:

According to the rules of statutory construction, and means the items must be considered together whereas or offers a choice of which one to use. Therefore, interpreting this part of the AUMF, the president’s action has to be based on both phrases.

The AUMF is clear — the force must be appropriate and killing an American citizen without judicial process is anything but. Although Awlaki appears to have subsequently evolved into an enemy combatant, the AUMF provides no authority to kill Awlaki.

In fact, Awlaki, was living and working as a Muslim imam in a suburb of Washington, D.C. Three days after the attacks, in response to his brother’s question about what Awlaki thought about the attack, he wrote, “I personally think it was horrible.”

Just under five months later, Awlaki was a guest speaker at one of the Department of Defense General Counsel’s luncheon speaker programs.

And even if the AUMF could be interpreted to include Awlaki, the Supreme Court has made it clear that Awlaki had a right to procedural due process regardless of the evidence against him. In Hamdi, the Court reiterated that the “interest of the erroneously detained individual” makes the right to due process absolute.

An MQ-1 Predator drone takes off from Balad Air Base in Iraq in 2009. U.S. Air Force photo

Fourth Amendment violation

Almost as an afterthought, on the last page of the Department of Justice’s 97-page legal memorandum, the authors make a Fourth Amendment argument, no doubt in anticipation that that killing of Awlaki could be interpreted as an illegal seizure.

The authors attempted to help justify Obama’s decision based upon dicta instead of the holding:

[T]he court has noted that “[w]here the officer has probable cause to believe that the suspect poses a threat of serious physical harm, either to the officer or to others, it is not constitutionally unreasonable to prevent escape by using deadly force.”

But this argument is misplaced because the government was citing dicta — which is extraneous legal commentary. In doing so, the memorandum misleads the president by ignoring the holding in this case which reads:

The Tennessee statute is unconstitutional insofar as it authorizes the use of deadly force against, as in this case, an apparently unarmed, non-dangerous fleeing suspect; such force may not be used unless necessary to prevent the escape and the officer has probable cause to believe that the suspect poses a significant threat of death or serious physical injury to the officer or others.

The use of “and” between the two clauses “prevent the escape” and “poses a significant threat of death or serious harm” are required to be read together. Since Awlaki was not attempting to escape (at least not until he heard the drone overhead, and escape was only from the car he was riding in) that clause is irrelevant and thus deadly force cannot be applied under the Fourth Amendment.

Conclusion

The president (or his staff) have something else to worry about. What if their actions in other countries violated the Rome Statutes of the International Criminal Court?

Even though the United States is not a signatory, the president’s actions in a country that is a signatory of the Rome States could result in an arrest warrant while on vacation because America’s definition of, for example, what is proportional under the Laws of Armed Conflict and the International Criminal Court differ.

Asking members of the armed forces to gamble on what is proportional at the risk of someday being charged with a war crime while sipping a café au lait on the Boulevard Saint Germain in Paris, provides worse odds than any Las Vegas crap table.

Buy ‘Black Flags: The Rise of ISIS’

Americans should take note of the Supreme Court’s warning that the executive branch was attempting to “condense power into a single branch of government;” and demand that notice and an opportunity to be heard, fundamental to the Bill of Rights, remain sacrosanct.

To fail to question the president is to allow him to continue toward the slippery slope of non-judicial killings at a time and place by defining any American citizen as an imminent threat. If the president can justify the killing of an American citizen living in Yemen, why can’t the same rationale be applied to an American citizen living in Cleveland?

James Perry Stevenson is the former editor of the Navy Fighter Weapons School’s Topgun Journal and the author of The $5 Billion Misunderstanding and The Pentagon Paradox.

We go to war so you don’t have to

May 15

Bex Walton/Flickr photo

A Missing Piece of Obama’s Terrorist ‘Kill Memo’ Still Haunts America

The lack of adversarial opinion for a 2011 drone strike on Anwar Al Awlaki could presage the killing of U.S. citizens in America

by JAMES PERRY STEVENSON

When U.S. Pres. Barack Obama considered the unprecedented step of intentionally killing an American citizen without judicial process, he asked for a legal opinion that would provide legal cover in case he was accused of a war crime.

Unfortunately, he did not ask for two opinions, one providing authority for killing a citizen and the other why it would be illegal, or at least we have no evidence for an opposing legal position. His request raises an interesting question — under what circumstances is it legal to kill an American citizen without due process?

Virtually all jurisdictions define “murder” as the “unlawful killing of a human being.” The operative word here is “unlawful.” If someone goes into a building on a shooting spree, no time exists for a warrant, a hearing or a trial.

Killing someone on a shooting spree would be a lawful killing because no time exists for a constitutionally-mandated legal process. Under these conditions, killing the shooter, regardless of his or her citizenship, is legal.

Obama’s request was for a similar legal justification. In this case, that killing radical preacher Anwar Al Awlaki would be a lawful killing. Then Attorney General Eric Holder supplied the 97-page legal memorandum, generated 14 months prior to the successful September 2011 assassination of Awlaki, who the U.S. government accused of being a key figure in Al Qaeda’s recruitment efforts.

The legal memorandum was designed to satisfy the president that killing Awlaki without a trial, without judicial process, and with the only “due process” coming from a handful of bureaucrats from the executive branch, would make it legal. In the process, Obama violated one of the fundamental premises in the Anglo-American legal system, one honed by centuries of precedent — the belief that through adversarial proceedings, the truth will emerge.

Obama did not ask for a rebuttal memorandum (or if he did, he never shared it), one offering countervailing considerations and containing opposing points of view — a memorandum that would indicate he had been fully briefed from all perspectives, an opinion that might have made him reach a different conclusion.

Since Obama appears to have asked for only one point of view, he did not have the benefit of hearing a contrarian legal perspective. So here is a non-lawyer’s attempt to show why he should not have killed Awlaki.

An MQ-1B Predator drone. U.S. Air Force photo

Imminent threat

First of all, if Obama had received an opinion representing Awlaki’s legal interests, he would have read that an international legal test for “imminent threat,” known as the Caroline Test, states that the threat must be “instant, overwhelming, and leaving no choice of means, and no moment for deliberation.”

“Imminent” used as an adjective modifying “threat” has also been defined by courts as “immediate danger, such as must be instantly met, such as cannot be guarded against by calling for the assistance of others or the protection of the law.”

Similar legal reasoning comes from a North Carolina Supreme Court case: “The right to kill in self-defense is based on the necessity, real or reasonably apparent, of killing an unlawful aggressor to save oneself from imminent death or great bodily harm at his hands.”

The legal memorandum Holder provided to Obama relies on the dubious and questionable legal argument that Awlaki was an “imminent threat.” The irony here is that if Awlaki were actually an “imminent threat,” no memorandum would have been necessary because anyone has the right to kill someone for killing unlawfully.

Buy ‘Objective Troy: A Terrorist, a President, and the Rise of the Drone’

But in an attempt to show that Awlaki was worse than an “imminent” threat, the legal memorandum defined him as a “continued imminent threat.” On the contrary, the only thing that “continued” was the government’s position that it could not capture Awlaki, a requirement it had under the Laws of Armed Conflict.

The government’s assertion that capturing Awlaki was not feasible strains credulity. To believe that SEAL Team Six could not have captured Awlaki, roaming the Yemeni desert, surrounded by a few friends and nothing else but hundreds of square miles of sand, is to ignore the more difficult captures by SEAL teams, such as the successful rescue of Richard Phillips bobbing in the Indian Ocean.

To be sure, there are times when government officials need to react quickly and order the killing of other human beings, without judicial or due process, but these kinds of exigencies were not present with Awlaki. The government chased Awlaki for over a year in an attempt to kill him, proving that as a threat he was far from imminent.

The Caroline Test provides a valid definition for the phrase “imminent threat,” a definition created by Secretary of State Daniel Webster in the 1830s, reaffirmed by the Nuremberg Tribunal in the late 1940s, and defined by the Supreme Court of North Carolina as “immediate danger, such as must be instantly met, such as cannot be guarded against by calling for the assistance of others or the protection of the law.”

Due process

When Awlaki was killed in September 2011, Holder was criticized his failure to provide Awlaki “due process,” a constitutional guarantee embedded in the Fifth Amendment. In response, Holder said that the Constitution promises due process but not judicial process.

Anwar Al Awlaki in Yemen in 2008. Muhammad ud-Deen/Wikimedia photo

The Department of Justice justified killing Awlaki without judicial process by citing the Supreme Court decision Mathews v. Eldridge, as though the Mathews decision stood for the principle that administrative hearings could replace judicial ones.

On the contrary, the Mathews case was about how much due process one is entitled to in administrative hearings on disability benefits. However, the Mathews case made it unambiguous that the greater the potential loss of rights, the greater the requirement for judicial as opposed to executive branch due process.

Amplifying the Mathews language, the Supreme Court wrote in Hamdi v. Rumsfeld — which dealt with the rights of detainees — that “procedural due process rules are meant to protect persons not from the deprivation, but from the mistaken or unjustified deprivation of life, liberty, or property.”

Moreover, the Hamdi case emphasized “the right to procedural due process is ‘absolute’ in the sense that it does not depend upon the merits of a claimant’s substantive assertions.”

Even in cases involving enemy combatants, in which the military wanted to shortcut the Constitution, the Supreme Court insisted “that a citizen-detainee seeking to challenge his classification as an enemy combatant must receive notice of the factual basis for his classification, and a fair opportunity to rebut the government’s factual assertions before a neutral decision maker.”

Noting the irony in the government’s argument, the Supreme Court wrote in United States v. Robel, “t would indeed be ironic if, in the name of national defense, we would sanction the subversion of one of those liberties … which makes the defense of the nation worthwhile.”

In spite of the executive branch’s attempt to minimize the role of the federal judiciary in wartime, the Hamdi court rejected the idea that war is an excuse to reduce due process to the equivalent of an administrative hearing:

Indeed, the position that the courts must forgo any examination of the individual case and focus exclusively on the legality of the broader detention scheme cannot be mandated by any reasonable view of separation of powers, as this approach serves only to condense power into a single branch of government. We have long since made clear that a state of war is not a blank check for the president when it comes to the rights of the nation’s citizens.

This leads us to ask — if the Supreme Court has taken the position that a detained citizen has a right to “rebut the government’s factual assertions before a neutral decision maker,” wouldn’t it provide these same or greater safeguards for an American citizen, scheduled to be killed, particularly when he does not fit the definition of an imminent threat?

Most likely yes, but the White House says otherwise

The legal memorandum the Department of Justice delivered to the president takes the position that the Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF), passed by Congress within days after Sept. 11, 2001, authorized the killing of Awlaki and suspended his Fifth Amendment rights under the U.S. Constitution.

The AUMF states:

The president is authorized to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons, in order to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States by such nations, organizations or persons.

But note that the AUMF emphasizes actions accused terrorists took in the past. Since Awlaki was not involved with any adversarial proceedings against the United States in the past, the AUMF does not apply to him personally. To the degree that he later became an adversary, his evolved status could and should be addressed without reliance on the AUMF.

Since the AUMF statute is brief enough, we can easily parse out its phrases in a search for relevancy:

- (1) The AUMF authorizes “necessary and appropriate force.”

According to the rules of statutory construction, and means the items must be considered together whereas or offers a choice of which one to use. Therefore, interpreting this part of the AUMF, the president’s action has to be based on both phrases.

The AUMF is clear — the force must be appropriate and killing an American citizen without judicial process is anything but. Although Awlaki appears to have subsequently evolved into an enemy combatant, the AUMF provides no authority to kill Awlaki.

- (2) against those nations, organizations, or persons

In fact, Awlaki, was living and working as a Muslim imam in a suburb of Washington, D.C. Three days after the attacks, in response to his brother’s question about what Awlaki thought about the attack, he wrote, “I personally think it was horrible.”

Just under five months later, Awlaki was a guest speaker at one of the Department of Defense General Counsel’s luncheon speaker programs.

- (3) he determines

- (4) planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001 or harbored such organizations or persons,

- (4) in order to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States by such nations, organizations or persons.

And even if the AUMF could be interpreted to include Awlaki, the Supreme Court has made it clear that Awlaki had a right to procedural due process regardless of the evidence against him. In Hamdi, the Court reiterated that the “interest of the erroneously detained individual” makes the right to due process absolute.

An MQ-1 Predator drone takes off from Balad Air Base in Iraq in 2009. U.S. Air Force photo

Fourth Amendment violation

Almost as an afterthought, on the last page of the Department of Justice’s 97-page legal memorandum, the authors make a Fourth Amendment argument, no doubt in anticipation that that killing of Awlaki could be interpreted as an illegal seizure.

The authors attempted to help justify Obama’s decision based upon dicta instead of the holding:

[T]he court has noted that “[w]here the officer has probable cause to believe that the suspect poses a threat of serious physical harm, either to the officer or to others, it is not constitutionally unreasonable to prevent escape by using deadly force.”

But this argument is misplaced because the government was citing dicta — which is extraneous legal commentary. In doing so, the memorandum misleads the president by ignoring the holding in this case which reads:

The Tennessee statute is unconstitutional insofar as it authorizes the use of deadly force against, as in this case, an apparently unarmed, non-dangerous fleeing suspect; such force may not be used unless necessary to prevent the escape and the officer has probable cause to believe that the suspect poses a significant threat of death or serious physical injury to the officer or others.

The use of “and” between the two clauses “prevent the escape” and “poses a significant threat of death or serious harm” are required to be read together. Since Awlaki was not attempting to escape (at least not until he heard the drone overhead, and escape was only from the car he was riding in) that clause is irrelevant and thus deadly force cannot be applied under the Fourth Amendment.

Conclusion

The president (or his staff) have something else to worry about. What if their actions in other countries violated the Rome Statutes of the International Criminal Court?

Even though the United States is not a signatory, the president’s actions in a country that is a signatory of the Rome States could result in an arrest warrant while on vacation because America’s definition of, for example, what is proportional under the Laws of Armed Conflict and the International Criminal Court differ.

Asking members of the armed forces to gamble on what is proportional at the risk of someday being charged with a war crime while sipping a café au lait on the Boulevard Saint Germain in Paris, provides worse odds than any Las Vegas crap table.

Buy ‘Black Flags: The Rise of ISIS’

Americans should take note of the Supreme Court’s warning that the executive branch was attempting to “condense power into a single branch of government;” and demand that notice and an opportunity to be heard, fundamental to the Bill of Rights, remain sacrosanct.

To fail to question the president is to allow him to continue toward the slippery slope of non-judicial killings at a time and place by defining any American citizen as an imminent threat. If the president can justify the killing of an American citizen living in Yemen, why can’t the same rationale be applied to an American citizen living in Cleveland?

James Perry Stevenson is the former editor of the Navy Fighter Weapons School’s Topgun Journal and the author of The $5 Billion Misunderstanding and The Pentagon Paradox.