ghazi52

PDF THINK TANK: ANALYST

- Joined

- Mar 21, 2007

- Messages

- 102,926

- Reaction score

- 106

- Country

- Location

CLAY POT IRRIGATION

Clay pot irrigation using ollas is a self-regulating gardening system that provides sub-surface watering of plants, that is simple, affordable, and easy to implement, making it ideal for small farmers and gardeners. Ollas — or unglazed, baked clay pots — are one of the most ancient technologies with evidence of their use being found on multiple continents in pre-modern civilizations with a relatively low-level of sophistication, bronze- and stone-age technologies, and predominantly agricultural economies. Thought to have originated in Northern Africa 4000 years ago, they have been used in China since the first century BC, and are still used in modern times in India, Iran, Brazil and Burkina Faso.

Ollas are great for permaculture because they represent a more eco-centric ideology, fostering a more eco-conscious and life affirming mindset, creating a better vision for the world. In this vision, humans become part of a larger, expanded network, like an interconnected web of life. This is unlike the West’s dominant, hegemonic, anthropocentric ideology, in which humans are at the top of the hierarchy, and nature exists not to be appreciated, understood, or tended to altruistically, but to be used and conquered. This attitude of unrestrained exploitation has led to the widespread destruction of the ecosystem, as our compulsion to exploit and over-extract the Earth’s resources, in the pursuit of short-term gains and glory, has already started to lead the ecosystem, its biosphere, and all the living and complex natural systems within it to exhaustion, and is rapidly bringing about the degradation of nature and environmental decay. Ollas provide a different mode of thinking that can help us to counter these destructive tendencies and savage ideologies, to work sustainably within the limits of natural systems, reduce waste and water consumption, and to better respect the environment and the resources it provides us, and so that we pay more attention how we use them and reduce waste.

The benefits of ollas are astounding, being incredibly valuable in gardens, for edible plant production, and for landscaping. Plants near the ollas grow faster, better, and stronger, making them very useful for plants prone to diseases from over watering, for revegetating areas affected by high-salinity, for tree-establishment, for use in arid climates, or for water conservation. They area also great for containers. They can be made with locally available materials and skills, they do not require pressurized or filtered water supplies, require watering only once every few days or once a week, and are less likely to be damaged by animals or clogged by insects. The much smaller quantities of water used reduces the amount of labor needed for watering. It also deters weeds, as the soil surface remains dry throughout the growing season, preventing surface plants from establishing. Snails and slugs are also easier to manage, as they tend to gather at the neck on the exposed surface, since it is cool and moist, and can easily be removed.

How They Work

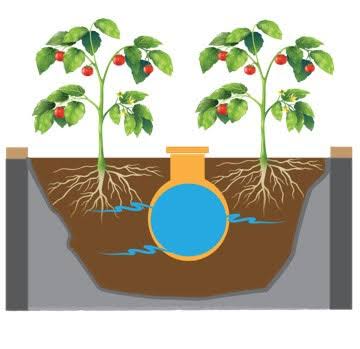

Ollas are simple, dried clay pots, often made by hand. They generally have a wide body, a rounded or flat bottom, and a narrow, tapered neck with an opening at the top. The pots are buried in the ground in the root zones of plants, with the neck partially exposed above the soil, and filled with water. This water is drawn by osmosis through the clay and naturally seeps out of the micro-pores in the terra-cotta surface, absorbing into the soil. Osmotic pressure between the clay and the soil provides a controlled, continuous supply of water. Eventually the plants’ roots will grow around the olla and automatically pull moisture when needed. When the soil has become fully saturated, the water seepage stops, and as it dries out again, the water flow commences and re-saturates the ground. Water usage is regulated by the needs of nearby plants, and inherently checks against over-irrigation.

Planting with ollas provides a very high efficiency, in terms of resource consumption, labor expended, and productive yields, delivering water underground and providing sub-surface irrigation directly to the roots. Soil moisture is consistently maintained at full capacity, giving the crops extra security against water stress. This also conserves water, using 50–70% less than normal surface-water irrigation, making it considerably better than drip irrigation, and virtually eliminates the surface-runoff and evaporation common in modern irrigation systems. Water loss due to deep percolation beyond the root zone is also reduced, if not completely eliminated.

Multiple studies in the developing world have demonstrated the benefits of olla irrigation, using less water than traditional agriculture while still maintaining high yields. Trials in India and Zimbabwe found that melons, cucumbers, and beans grown with buried clay pots used much less water than conventional flood- and basin-irrigation. The following tables compare the productivity and water usage of different methods and plant types.

Method Productivity in plant kg per cubic meter of water

closed furrow 0.7

sprinkler 0.9

drip 1.4

buried clay pot up to 7

Finding And Making Ollas

Ollas may be difficult to find in the industrialized world, and could be prohibitively expensive to deploy in large numbers. A few sources produce and sell clay pots specifically for irrigation, one of which is “Growing Awareness Urban Farm” in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Also check out local or online gardener’s supply and country ceramics stores. Whether you buy them or make them, the pots you use need to be unglazed, porous clay pots, although the neck of the olla can be glazed or painted to prevent evaporation. To test your pots for porosity, spray them with a little water. If the surface becomes damp immediately, then they should work. If you have the opportunity, fill it with water and come back after a couple of hours to check if the outside is wet. If this occurs, then the micro-pores should allow enough leakage to wet the ground around it, but not so much that it oversaturates it.

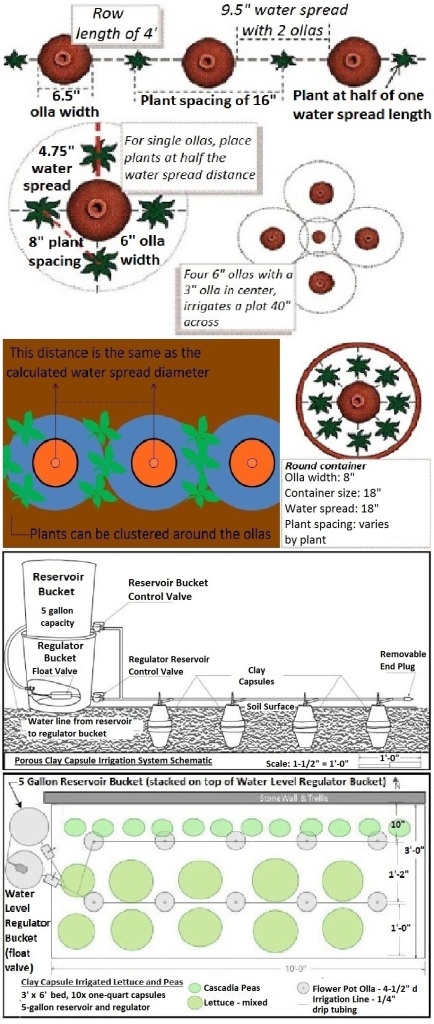

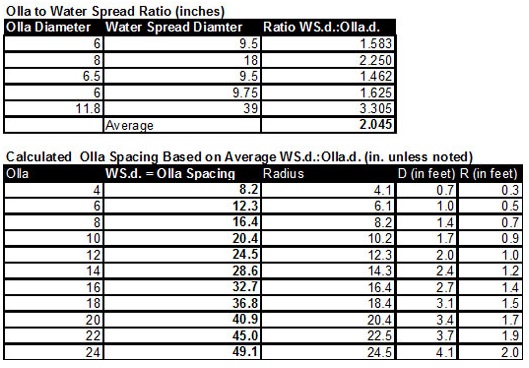

The optimal size and shape of the olla depen

ds on the plants being irrigated, the density of planting, and the time desired between refills. In general, a more tapered, flat-bottomed vessel with a large body and a narrow neck should be more efficient due to an increased surface area and increased water spread. The mouth could either be wide or narrow, but a narrow opening reduces evaporation and the risk of contamination. The neck shouldn’t be too long or fragile, but it should be tall enough to apply some surface mulch to cover it without spilling into the opening.

One should match olla porosity, size, and shape to plants’ water needs, root size, and root distribution. Each pot will water the plants within its immediate area. The larger the pot, the greater the area it covers, and the less often you have to refill it. As a general guide, smaller ollas are better for container gardening and automatic irrigation systems, and larger ollas are better for larger containers, outdoor gardens, or tree establishment. For most applications, two- to five-liter sizes should be suitable, although capacities of 5- to 12-liters are useful for irrigating vine crops. If you’re using a stand-alone system, that is – if you refill the ollas by hand, supplying water intermittently – then it’s best to use larger pots. If using an automatic watering system, with a constant supply of water, then you can use smaller ollas.

The Olla Global Bucket System

A more affordable alternative to buying premade ollas is to build your own. Different methods are available, including making them by hand out of wet clay using a potter’s wheel, the coil-method, or plaster of Paris molds. However, the cheapest and easiest method uses two ordinary terra-cotta pots, about 25 cm (10 in.) wide, bought inexpensively from the store. 15-inch ones, for instance, can cost as little as $1 per pot, or less for smaller ones.

Take one pot, sitting upright, and cover the hole in the bottom with a spare tile, a cork, or a wood plug, and seal it with waterproof, silicone caulk or Gorilla Glue. Be careful with the glue you use, as the ingredients in some are toxic, and may not be food safe when exposed to water over long periods of time. Black silicone caulk is the best to use as it is sunlight resistant. If you’re using a piece of tile along with the caulk to plug the hole, be sure to inspect inside the pot for roughness. Rough edges increase the surface area, which increases the effectiveness of the adhesive.

Insert the tile from the inside the pot, and use it to cover the hole on the bottom. Seal it with caulk, press down firmly, and let it dry for 24 hours. If the drain holes are small enough, you can set the pots on a sheet of wax paper, insert the nozzle of the caulk gun into the hole, and fill it up with a small amount of caulk. Let it sit for about 8 hours and carefully peel it from the paper. You can also simply put some masking tape over the outside of the hole on the bottom of the pot, then turn it over and fill the inside of the hole with caulk.

After finishing the first pot, take another one, flip it upside-down, and set it on top of the first one, matching the rims together. Some of the pots may not be completely round, and you may have to try several different pairs before finding a match. Test them again to make sure their rims fit as closely as possible, and draw a pencil mark on the side to indicate the point of best alignment.

Apply a bead of caulk along the rim of one pot, making sure there are no thin spots that could contain air gaps. Gently set the other pot on top, line up the pencil marks, and smear the caulk around the edges with the tip of your finger to smooth it out. The glue should expand when it dries, creating a water-tight seal. To reduce leakage, apply more caulk or glue around the exterior of any holes or edges. Let the caulk set up for 24 hours. If using Gorilla Glue, first dampen the rims of both pots by dipping them in water for about 10 seconds. Apply the glue to one pot, then set it on top of the other, and wait about 60 minutes for the glue to set. Be sure to put pressure on the pots using tape or rock-weights while the adhesive cures.

To test the seals on your ollas after fitting them together, plug up one hole with a finger (if it’s not already sealed shut) and blow into the other. If you feel back pressure building, then the seal should hold. On smaller pots the silicone caulk may not hold well for long, because of the low surface area around the rim of the pot, and approximately 10% of them will fail at the glue joint. To prevent this, try using Gorilla Glue instead of the caulk to glue the pots together. You could also rough up the rims of the pots with sandpaper to increase their surface area.

This same system could be built using a single flower pot with a terracotta plate glued over the opening, and turned upside down. For shallow-rooted plants like radishes, you could potentially modify the shape of the ollas to make them flatter and rounder, by gluing two clay saucers or plates (instead of pots) together to make a disc-shaped vessel. This way you could bury it about 6-inches down in the dirt, and plant in a wide, circular area right on top of it.

Clay pot irrigation using ollas is a self-regulating gardening system that provides sub-surface watering of plants, that is simple, affordable, and easy to implement, making it ideal for small farmers and gardeners. Ollas — or unglazed, baked clay pots — are one of the most ancient technologies with evidence of their use being found on multiple continents in pre-modern civilizations with a relatively low-level of sophistication, bronze- and stone-age technologies, and predominantly agricultural economies. Thought to have originated in Northern Africa 4000 years ago, they have been used in China since the first century BC, and are still used in modern times in India, Iran, Brazil and Burkina Faso.

Ollas are great for permaculture because they represent a more eco-centric ideology, fostering a more eco-conscious and life affirming mindset, creating a better vision for the world. In this vision, humans become part of a larger, expanded network, like an interconnected web of life. This is unlike the West’s dominant, hegemonic, anthropocentric ideology, in which humans are at the top of the hierarchy, and nature exists not to be appreciated, understood, or tended to altruistically, but to be used and conquered. This attitude of unrestrained exploitation has led to the widespread destruction of the ecosystem, as our compulsion to exploit and over-extract the Earth’s resources, in the pursuit of short-term gains and glory, has already started to lead the ecosystem, its biosphere, and all the living and complex natural systems within it to exhaustion, and is rapidly bringing about the degradation of nature and environmental decay. Ollas provide a different mode of thinking that can help us to counter these destructive tendencies and savage ideologies, to work sustainably within the limits of natural systems, reduce waste and water consumption, and to better respect the environment and the resources it provides us, and so that we pay more attention how we use them and reduce waste.

The benefits of ollas are astounding, being incredibly valuable in gardens, for edible plant production, and for landscaping. Plants near the ollas grow faster, better, and stronger, making them very useful for plants prone to diseases from over watering, for revegetating areas affected by high-salinity, for tree-establishment, for use in arid climates, or for water conservation. They area also great for containers. They can be made with locally available materials and skills, they do not require pressurized or filtered water supplies, require watering only once every few days or once a week, and are less likely to be damaged by animals or clogged by insects. The much smaller quantities of water used reduces the amount of labor needed for watering. It also deters weeds, as the soil surface remains dry throughout the growing season, preventing surface plants from establishing. Snails and slugs are also easier to manage, as they tend to gather at the neck on the exposed surface, since it is cool and moist, and can easily be removed.

How They Work

Ollas are simple, dried clay pots, often made by hand. They generally have a wide body, a rounded or flat bottom, and a narrow, tapered neck with an opening at the top. The pots are buried in the ground in the root zones of plants, with the neck partially exposed above the soil, and filled with water. This water is drawn by osmosis through the clay and naturally seeps out of the micro-pores in the terra-cotta surface, absorbing into the soil. Osmotic pressure between the clay and the soil provides a controlled, continuous supply of water. Eventually the plants’ roots will grow around the olla and automatically pull moisture when needed. When the soil has become fully saturated, the water seepage stops, and as it dries out again, the water flow commences and re-saturates the ground. Water usage is regulated by the needs of nearby plants, and inherently checks against over-irrigation.

Planting with ollas provides a very high efficiency, in terms of resource consumption, labor expended, and productive yields, delivering water underground and providing sub-surface irrigation directly to the roots. Soil moisture is consistently maintained at full capacity, giving the crops extra security against water stress. This also conserves water, using 50–70% less than normal surface-water irrigation, making it considerably better than drip irrigation, and virtually eliminates the surface-runoff and evaporation common in modern irrigation systems. Water loss due to deep percolation beyond the root zone is also reduced, if not completely eliminated.

Multiple studies in the developing world have demonstrated the benefits of olla irrigation, using less water than traditional agriculture while still maintaining high yields. Trials in India and Zimbabwe found that melons, cucumbers, and beans grown with buried clay pots used much less water than conventional flood- and basin-irrigation. The following tables compare the productivity and water usage of different methods and plant types.

Method Productivity in plant kg per cubic meter of water

closed furrow 0.7

sprinkler 0.9

drip 1.4

buried clay pot up to 7

Finding And Making Ollas

Ollas may be difficult to find in the industrialized world, and could be prohibitively expensive to deploy in large numbers. A few sources produce and sell clay pots specifically for irrigation, one of which is “Growing Awareness Urban Farm” in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Also check out local or online gardener’s supply and country ceramics stores. Whether you buy them or make them, the pots you use need to be unglazed, porous clay pots, although the neck of the olla can be glazed or painted to prevent evaporation. To test your pots for porosity, spray them with a little water. If the surface becomes damp immediately, then they should work. If you have the opportunity, fill it with water and come back after a couple of hours to check if the outside is wet. If this occurs, then the micro-pores should allow enough leakage to wet the ground around it, but not so much that it oversaturates it.

The optimal size and shape of the olla depen

ds on the plants being irrigated, the density of planting, and the time desired between refills. In general, a more tapered, flat-bottomed vessel with a large body and a narrow neck should be more efficient due to an increased surface area and increased water spread. The mouth could either be wide or narrow, but a narrow opening reduces evaporation and the risk of contamination. The neck shouldn’t be too long or fragile, but it should be tall enough to apply some surface mulch to cover it without spilling into the opening.

One should match olla porosity, size, and shape to plants’ water needs, root size, and root distribution. Each pot will water the plants within its immediate area. The larger the pot, the greater the area it covers, and the less often you have to refill it. As a general guide, smaller ollas are better for container gardening and automatic irrigation systems, and larger ollas are better for larger containers, outdoor gardens, or tree establishment. For most applications, two- to five-liter sizes should be suitable, although capacities of 5- to 12-liters are useful for irrigating vine crops. If you’re using a stand-alone system, that is – if you refill the ollas by hand, supplying water intermittently – then it’s best to use larger pots. If using an automatic watering system, with a constant supply of water, then you can use smaller ollas.

The Olla Global Bucket System

A more affordable alternative to buying premade ollas is to build your own. Different methods are available, including making them by hand out of wet clay using a potter’s wheel, the coil-method, or plaster of Paris molds. However, the cheapest and easiest method uses two ordinary terra-cotta pots, about 25 cm (10 in.) wide, bought inexpensively from the store. 15-inch ones, for instance, can cost as little as $1 per pot, or less for smaller ones.

Take one pot, sitting upright, and cover the hole in the bottom with a spare tile, a cork, or a wood plug, and seal it with waterproof, silicone caulk or Gorilla Glue. Be careful with the glue you use, as the ingredients in some are toxic, and may not be food safe when exposed to water over long periods of time. Black silicone caulk is the best to use as it is sunlight resistant. If you’re using a piece of tile along with the caulk to plug the hole, be sure to inspect inside the pot for roughness. Rough edges increase the surface area, which increases the effectiveness of the adhesive.

Insert the tile from the inside the pot, and use it to cover the hole on the bottom. Seal it with caulk, press down firmly, and let it dry for 24 hours. If the drain holes are small enough, you can set the pots on a sheet of wax paper, insert the nozzle of the caulk gun into the hole, and fill it up with a small amount of caulk. Let it sit for about 8 hours and carefully peel it from the paper. You can also simply put some masking tape over the outside of the hole on the bottom of the pot, then turn it over and fill the inside of the hole with caulk.

After finishing the first pot, take another one, flip it upside-down, and set it on top of the first one, matching the rims together. Some of the pots may not be completely round, and you may have to try several different pairs before finding a match. Test them again to make sure their rims fit as closely as possible, and draw a pencil mark on the side to indicate the point of best alignment.

Apply a bead of caulk along the rim of one pot, making sure there are no thin spots that could contain air gaps. Gently set the other pot on top, line up the pencil marks, and smear the caulk around the edges with the tip of your finger to smooth it out. The glue should expand when it dries, creating a water-tight seal. To reduce leakage, apply more caulk or glue around the exterior of any holes or edges. Let the caulk set up for 24 hours. If using Gorilla Glue, first dampen the rims of both pots by dipping them in water for about 10 seconds. Apply the glue to one pot, then set it on top of the other, and wait about 60 minutes for the glue to set. Be sure to put pressure on the pots using tape or rock-weights while the adhesive cures.

To test the seals on your ollas after fitting them together, plug up one hole with a finger (if it’s not already sealed shut) and blow into the other. If you feel back pressure building, then the seal should hold. On smaller pots the silicone caulk may not hold well for long, because of the low surface area around the rim of the pot, and approximately 10% of them will fail at the glue joint. To prevent this, try using Gorilla Glue instead of the caulk to glue the pots together. You could also rough up the rims of the pots with sandpaper to increase their surface area.

This same system could be built using a single flower pot with a terracotta plate glued over the opening, and turned upside down. For shallow-rooted plants like radishes, you could potentially modify the shape of the ollas to make them flatter and rounder, by gluing two clay saucers or plates (instead of pots) together to make a disc-shaped vessel. This way you could bury it about 6-inches down in the dirt, and plant in a wide, circular area right on top of it.