Zen0

BANNED

- Joined

- Dec 28, 2016

- Messages

- 1,222

- Reaction score

- -16

- Country

- Location

China’s failing satellite is just one example of a massive space debris problem

By Rick Noack Email the authorMarch 29 at 11:36 AM

1:18

Chinese satellite will soon come crashing down into Earth

The Tiangong-1 satellite is expected to reenter Earth's atmosphere uncontrolled around April 1. This is what it would look like. (Claritza Jimenez/The Washington Post)

BERLIN — If you want to catch a last glimpse of Chinese satellite Tiangong-1, you better hurry. Circling the Earth at a speed of 17,500 miles per hour every 90 minutes, the 19,000-pound satellite will probably have vanished by the end of this weekend, to reappear as a fireball for up to a minute or more somewhere over the skies of southern Europe — or perhaps somewhere else.

While nobody can be certain where exactly the disintegrating satellite may literally fall from the sky — with pieces weighing up to 220 pounds expected to hit Earth’s surface — the satellite’s fate has long been sealed. Even if you miss this one, scientists say there’s plenty more to come in the junk-strewn skies of our planet’s near orbit.

[A Chinese spacecraft is falling out of the sky. It’s not supposed to happen like this.]

The first warning signs for the Chinese station came in 2016 when it failed to respond to commands by its operators. Tiangong-1, which translates as “heavenly palace,” would eventually, according to my colleagues, turn “into a man-made” meteor.

In its latest estimate, the European Space Agency (ESA) predicts the satellite pieces will probably hit Earth “from midday on 31 March to the early afternoon of 1 April (in UTC time)." UTC is ahead of Eastern Time by four hours. The estimate will continue to be updated by ESA over the next days.

While the threat of the debris hitting a human is extremely small, the drama that could unfold over Europe’s skies this weekend may be only be a first glimpse into a problem that will worsen over the next decades, according to some bleak predictions.

[T-minus one week until China’s space lab crashes to Earth. Here’s what it will look like.]

The European Space Agency estimates that there are now more than 170 million pieces of space debris in circulation, though only 29,000 of those are larger than about four inches. While the smaller space debris objects may not pose a threat to Earth because they would disintegrate before reaching the surface, “any of these objects can cause harm to an operational spacecraft. For example, a collision with a (four-inch) object would entail a catastrophic fragmentation of a typical satellite,” according to the European Space Agency. Smaller pieces could still destroy spacecraft systems or penetrate shields, possibly making bigger satellites such as Tiangong-1 unresponsive and turning them into massive pieces of debris themselves.

Since the first satellites were launched in the mid-20th century, Earth’s orbit has long been treated by nations as a waste site nobody felt responsible for. Spent rockets or old satellites now mingle with other pieces of trash left behind by human space programs. All of those pieces zoom around faster than speeding bullets.

12:34

Watch man-made objects journey from the outer solar system back to Earth

Journey from our solar system to Earth and explore the man-made objects along the way. (European Space Agency)

And while the international community is gradually becoming more aware of the challenges this poses, much of the damage is already done.

Speaking at a conference in 2011, Gen. William Shelton, a commander with the U.S. Air Force Space Command, predicted much of the orbit around Earth “may be a pretty tough neighborhood ... in the not too distant future,” according to the astronomy news website Space.com. The U.S. military and NASA are both in charge of perhaps the most elaborate scheme to track objects bigger than four inches to predict their flight paths and move active equipment out of the way.

The problem, Shelton indicated at the time, is that there's already enough debris in space to cause an exponential rise in the number of circulating pieces. The more pieces there are, the higher the likelihood that they will eventually collide, creating even more smaller objects that can still be dangerous to other satellites or space labs.

On Earth, ecosystems can sometimes fix themselves to some extent, even if it takes decades or hundreds of years. But in space, the problem of debris will only get worse.

One proposed solution would be to persuade nations to limit their debris and to prevent a repeat of past mistakes. China, for example, is estimated to have produced up to 25 percent of today’s objects in circulation during an antisatellite test in 2007 in the low Earth orbit.

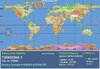

On these NASA graphics, you can see why the international community was outraged when China added to that zone’s debris density. Congestion isn’t spread evenly around Earth: While there are some scattered pieces farther away, there is a concentration of objects within the so-called geosynchronous region, at about 22,235 miles altitude.

China has continued its military missile tests since 2007, although it has refrained from destroying another satellite in orbit. Observers still fear that other nations may launch their own antisatellite programs, provoking a sort of arms race in space.

With more than 50 nations now operating their own space programs, initiatives to limit the release of space debris have hardly become any easier. Some technological advances have had a limited impact — for instance by making spent rocket boosters fall back to Earth quicker than in the past. (Following that rationale, one could argue that this weekend’s satellite crash may in fact help to decongest the orbit.) Meanwhile, other nations, such as Britain and Switzerland, have experimented with schemes to clean up the mess by collecting the debris in circulation. But the proposed programs are costly and inefficient, legal challenges aside.

“There are no salvage laws in space. Even if we had the political will to [salvage junk], which I don’t think we do, we couldn’t bring down the big pieces because we don’t own them,” Joan Johnson-Freese, a Naval War College professor, told The Washington Post in 2014.

That’s why some academics are arguing that the lower orbit might soon be lost altogether. Instead, they believe, scientists should develop smaller satellites that can circulate closer to Earth — and in a safe distance from a part of the orbit that may eventually become a satellite kill zone.

More on WorldViews:

Today's WorldView newsletter

What's most important from where the world meets Washington

Three big questions about a Trump-Kim summit

She was Ukraine’s ‘Joan of Arc.’ Now she’s accused of plotting a coup in Kiev.

Kim Jong Un follows his father’s blueprint with a secret armored train journey to China