third eye

ELITE MEMBER

- Joined

- Aug 24, 2008

- Messages

- 18,519

- Reaction score

- 13

- Country

- Location

Smoked gun An Indian soldier with a howitzer blown up by a direct hit

“This is a devils’ war. When will it end?” Thus wrote a wounded Sikh soldier in England to his father back home in February 1915. In fact, the war had only just begun. When Germany invaded France in August 1914, the Lahore and Meerut infantry divisions set sail from Karachi and Bombay, landing in Marseilles in late September and early October. From there, they were rapidly despatched to the frontlines to press back the billowing German offensive between Ypres and La Bassee. Writing three years later, Lord Curzon observed that “the Indian Expeditionary Force arrived in the nick of time...it helped to save the cause both of the Allies and of civilisation.” Indeed, without the Indian army holding a third of the British front until Christmas, Germany may well have emerged victorious in 1914. Curzon went on to write that the “letters of the Indian soldiers to their folk at home would stand comparison with any that the official post-bag has conveyed to England from our own heroes at the front, in their uncomplaining loyalty, their high enthusiasm, their philosophic endurance, and their tolerant acceptance of privations and sufferings of war”. The former viceroy of India was characteristically overstating his case. As the letter quoted above suggests, Indian soldiers’ feelings about the war were rather more mixed.

Yet the question remains: what motivated these men to fight in World War I? The Indian army had long functioned as an imperial fire brigade, taking part in colonial expeditions in Africa, the Middle East and China. Closer home, it had campaigned in Burma and Afghanistan, Tibet and Sikkim. None of these wars and campaigns, however, approached the scale and intensity of the Western front in World War I. This was mass industrial warfare in all its brutality. As a Garhwali soldier wrote home in early 1915, “It is very hard to endure the bombs, father.... There is no confidence of survival. The bullets and cannonballs come down like snow. The mud is up to a man’s middle. The distance between us and the enemy is fifty paces.... The numbers that have fallen cannot be counted.”

From far away Men of the 6th Jat Cavalry take a hookah break in France, 1915

The two Indian divisions that fought in France for under a year comprised nearly 24,000 men. In the same year, these divisions received around 30,000 replacements from India—a casualty rate of well over a hundred per cent. The overall figures tell a similar story. The Indian army, which numbered about 1,55,000 at the onset of war, swelled at one point to 5,73,000 combatants. India provided up to 1.1 million combatants, and a total of up to 1.7 million men. The Indian army’s losses were in the range 62-64,000 soldiers killed or dead from wounds. The numbers seem even starker because more than half of these were from a single province: Punjab. It bears recalling that the Indian army remained a volunteer force—even though the Raj did resort to coercive measures for recruitment at some points. Why did so many Indians sign up to fight in so deadly a war being waged so far from their homes?

Vast numbers of Indians lost their lives in World War I, a war fought at an industrial scale of brutish intensity.

Letters written by Indian soldiers—some of which have fortunately survived in censor reports and have been admirably edited by the historian David Omissi—suggest that several motivations were at work. The material benefits of military service understandably played an important role. Joining the Indian army meant partaking of a well-established system of pay, perquisites and patronage. As former soldier Lehna Ram reminded his son Heta Ram, who was serving in France, “I served the state for 21 years and now receive a pension of `40 from the sirkar. I live in peace and comfort.” And the war effort led to an expansion of this system. “The sirkar has increased the rates both of pay and pension,” wrote Kala Khan to a kinsman in Punjab, “and at the same time has granted free rations.”

However, the predominant motivation of the soldiers was the quest for izzat. Variously translated as honour, reputation, prestige or standing, the notion of izzat had several connotations. At one level, it was a simple question of loyalty. As Mansa Ram observed in a missive, “It is fitting for anyone who has eaten the salt of the great government to die. So it is very necessary and proper for you to be loyal to the government, for that is the reason why it employs you.” Sentiments of loyalty, however, ranged beyond the impersonal entity of the government and were frequently extended to the person of the king-emperor. At the same time, the notion of loyalty was not entirely divorced from material considerations. Mohammad Ali Bey advised a friend serving in India: “If you people do not show your loyalty to the sirkar at this juncture, the sirkar will not overlook it, and there will be no prosperity for your children.”

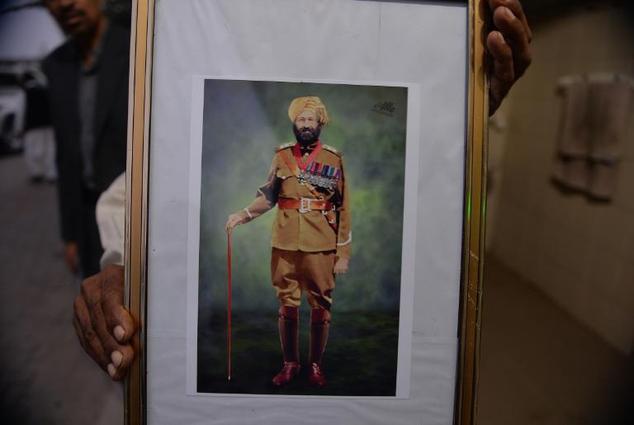

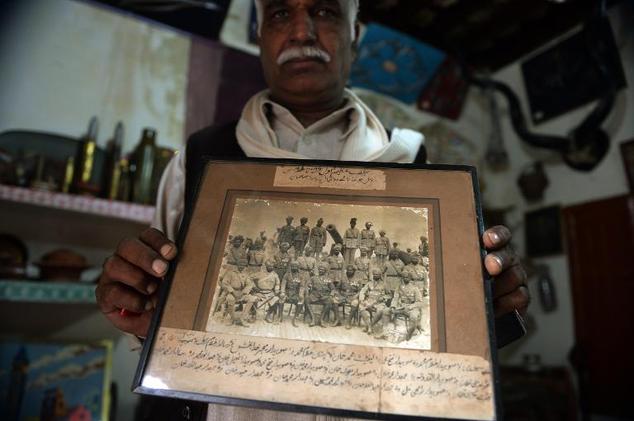

Letters home from the frontlines

Izzat also operated through the soldier’s caste or clan identity. This is not surprising, given that the bulk of the Indian army came from the middle peasantry of northern India. Soldiers believed that by fighting they were raising the status of their caste or clan: “This is the first occasion on which our quivering arm is showing to a tyrannous enemy on the fields of Europe the jewel of the real Rajput blood.... The time is at hand that our reputation will be exalted.” Conversely, by failing to do one’s duty, one was bringing dishonour and disrepute to the caste or clan. Religion, too, seems to have played a role in constructing this notion of izzat. “Do not show your back to the enemy,” wrote Murarao Shinde to his son serving in France, “for your religious teaching forbids this.”

More interestingly, izzat acquired a particular meaning in the context of modern trench warfare with its compression of space and mass: that of standing by one’s comrades in combat. Concerns about shame and dishonour in this environment were important negative impulses in keeping the Indian soldiers going. This is especially clear when we consider the fact that most soldiers who were once wounded were loath to return to the front—and yet many of them did. Rajaram Jadhow informed his colleague that he had “tried hard to rejoin you but without result, because it is not possible to overcome the doctor’s objections.” Yet he could not shield his sense of shame: “I am not afraid of dying, but I cannot speak.... I hear that the weak are sent back [to the front] and should it be your wish, and if you can so arrange it, I ask you to make the effort [to let me rejoin you].”

Letters home from the frontlines

Indians rationalised their fate with overt reference to loyalty and izzat, bound up with the expected material benefits.

The experience of serving in Europe also unsettled the traditional values and hierarchies that the soldiers had taken for granted. “If you look at the condition of things in this country [France],” noted Tara Singh, “you cannot but see that all men here are considered equal in the sight of God.” In particular, they tended to see the role of women in European societies as being rather more modern that it was. Indian soldiers’ interaction with European women was closely regulated. The British authorities were concerned that sexual relations between them would be “most detrimental” to the prestige of their rule in India. This did not, of course, prevent such relations from budding in the hothouse of war. “The ladies are very nice and bestow their favours upon us freely,” wrote Balwant Singh from France. “But contrary to the custom in our country, they do not put their legs over the shoulders when they go with a man.”

Above all, their encounters with Europe drove home to Indian sepoys the abject conditions prevailing in India. As one soldier wrote, “When one considers this country [Britain] and these people in comparison with our country and our own people, one cannot but be depressed. Our country is very poor and feeble and its lot is very depressed.” Another observed, in similar vein, “The Creator has shown the perfection of his beneficence in Europe, and we people [Indians] have been created only for the purpose of completing the totality of the world.”

Letters home from the frontlines

This is not to suggest that these encounters with Europe were understood through the framework of “nationalism”. The bulk of the Indian army in World War I seemed to have little interest in political matters, except insofar as they related to issues as such waging war against the Ottoman empire and the Caliphate, which stemmed from their religious concerns.

Nevertheless, there does seem to have been an expectation that India’s sacrifices in the war would pave the way for its own betterment. Mahomed Hasan wrote to a sepoy in France that educational opportunities in India were expanding at all levels, schools, colleges and universities: “We Indians are acquiring educational fitness.” He added that “if we Indians bring back to India the flag of victory which we have helped win for our King George, we shall have proved our fitness and will be entitled to self-government.”

The explicitly political viewpoint of this writer may have been untypical. Yet the layers of expectation that lurked beneath the letters of the sepoys are palpable. And the brutal belying of these expectations would pave the way for the rise of mass nationalism in India.

Srinath Raghavan, a former army officer, is a senior fellow at the Centre for Policy Research, New Delh