Mujahid Memon

SENIOR MEMBER

- Joined

- Apr 24, 2012

- Messages

- 2,820

- Reaction score

- -4

- Country

- Location

The Memon predisposition towards frugality is iconic within Pakistan, but they celebrate their stereotyping as an achievement; a tribute to their enduring prosperity and resilience.

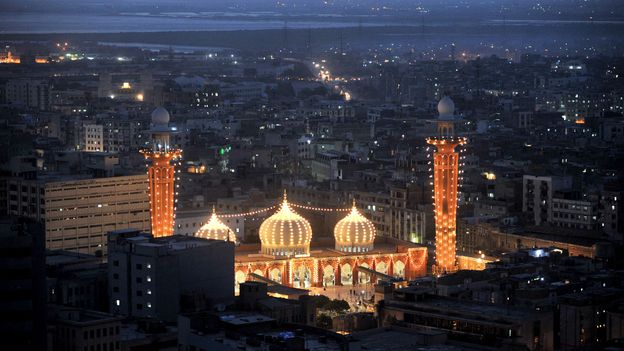

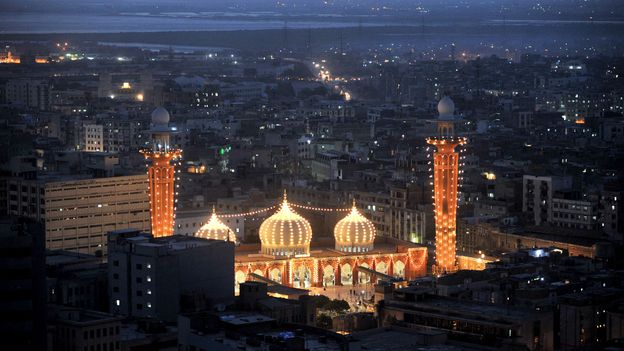

As I circled to find a parking spot, I was awestruck by the stately mansion in the upscale neighbourhood of Karachi. Casually, my sister-in-law remarked that the equally impressive estate across the road also belonged to Bilquis Sulaman Divan, the Memon (an ethnic sub-group of Sunni Muslims) and ex-colleague of hers that we were visiting. Flanked by perfectly manicured hedges, the home’s colonial architecture and sprawling, expansive gardens spoke of affluence and hinted at greater opulence within.

But on approaching, we were marched straight past the grand main entrance and guided instead to a simple room crammed with the necessities of life, including a ramshackle sewing machine by the door, threadbare sofas and an ancient refrigerator.

Although Divan and her sister – who also live with her sister’s husband and their adult daughter – have almost incalculable wealth, as owners of a bottle manufacturing plant and heiresses to their late father’s fruit-exporting company, they choose instead to spend most of their time not in the mansion’s grand rooms, but in one small living quarter. The rest of the estate has been rented out to an elite private school, which is where Divan and my sister-in-law worked for more than two decades.

Why, despite such abundance, did these people live so frugally, I wondered?

Divan and her family are not the only ones. As I would soon learn, the entire minimalist Memon community takes pride in pinching pennies.

The concentration and preservation of wealth, as the last vestiges of power and dominion that the displaced Memons clung to, has been integral to their quest for identity. And while safeguarding their security through financial stability has become second nature to the Memon diaspora, the Memons of Karachi have an especially interesting – and successful – story.

Part of what sets the Memons of Karachi apart from their Indian counterparts is the memory of the harrowing time of Partition in 1947. While the Memons who stayed in present-day India continued to have access to the established businesses and industries of their forefathers, those who uprooted their businesses and migrated had to start from scratch, setting the family’s financial status back by years, if not generations.

“My grandfather came to Pakistan, literally barefoot, asking people for work. He built his empire slowly and diversified. From childhood, we’re instilled with an awareness – and understanding – of the value of hard-earned money. It’s part of our daily narrative. It’s how we survived. And we take care to give back,” said Anila Parekh, granddaughter of the late Memon industrialist and philanthropist Ahmed Dawood.

For the Memons of Karachi, each “paisa” (Memoni for “money”, but also the Urdu word for “cent”) accumulated and saved is an ode to trials that they overcame. Although they now control the majority of many business sectors in Pakistan, including the textile industry, education sector, fertiliser industry and financial securities, respect for money is deeply engrained in Memon ethos, making for a thrifty legacy that they take pride in preserving.

“It’s not ‘don’t spend’ – it’s ‘don’t waste’,” clarified Nadeem Ghani, a Memon and dean of Academia Civitas and Nixor College, an elite school and college in Karachi. “Being frugal,” he said, “has an element of humility. It’s a manifestation of respect. We don’t shy away from placing a monetised value on our comfort.”

A Memon of Karachi would much rather make do with less or err on the side of caution than spend unnecessarily. It’s a sort of indemnification against unpredictably hard times; an homage to previous hardships.

The subsequent reverent handling of resources drives community members to cherish what they have and stretch it as far as possible. Hira Khatri, a Memon living in Karachi, told me that hand-me-downs in most Memon households typically go through multiple cycles, extending to include cousins and even closely aged uncles and aunts. Turning off the light or fan when you leave the room is important in any household, she said, but in Memon families, forgetting to do so is a cardinal offence. Memon children are taught to embrace accountability – and accounting.

“Monthly grocery money simply wasn’t for snacks; we had to pay to replenish the refrigerator out of our pocket money. We also paid for offences. Fifteen Pakistani rupees (£0.07) was the going rate for forgetting to flush the toilet or turn off the lights – this money was accumulated to pay for our internet connection,” Khatri said, recalling her family’s distinct care for overheads.

Interestingly, the Memon lifestyle closely resembles “new” guidelines governing the zero-waste movement.

“Reduce, reuse and recycle – made mainstream a couple of decades ago – has been part of the Memon tradition for centuries. It just lacked the righteous tag line,” Ghani said.

Certain themes were recurrent in many of the Memon households I visited, such as preferring to consume what is in season and locally grown, or meal planning to ensure there is no food wastage. “At dinner, we have one vegetable-based dish and one meat-based entrée – anything beyond that and I am questioned about the wastage,” Parekh said.

According to Parekh and Manahyl Ashfaq, an aspiring Memon videographer, it is a point of pride for produce to be peeled ever so thinly to reduce wastage. In fact, using vegetable peelers is considered extravagant, with a knife being used to scrape off the peel instead, if possible.

“Memons don’t suspend reality to splurge and have an aspirational moment beyond their existence,” Ghani explained over the phone.

Ghani was overseas for a week, driving cross-country through the US, taking his 18-year-old son to look at Ivy League schools. That day it was Princeton – but he unabashedly shared that he was wearing apparel from Wal-Mart: solid, reliable and good value for money. Citing Memon dining conventions as an example of frugality, he continued, “It’s less about the image we cultivate, and more about optimal usage. To us, it would be disingenuous not to use that free appetiser coupon – whether during the first date or years after marriage.”

To uninitiated outsiders, then, extravagant Memon weddings with grand marquees, 10-course menus and bridal outfits that can run upwards of 10 lakh rupees (almost £5,000), seem incongruous with their frugal ways, but essentially, the functions epitomise their regard for guests. The distinguishing feature of a Memon wedding is the guest list, which can easily run into the thousands. When asked about the paradox, Moshin Adhi, president of the Memon Professional Forum, which provides vocational training and networking opportunities to Memon youth, was quick to respond: “Weddings are great networking and branding opportunities!” Calculated? Perhaps. But also genuinely upfront.

Memon frugality may mirror the larger zero-waste movement, but their habit of earnestly and openly discussing savings and money is what sets them apart. Parekh explained it best:

“When your men sit down for dinner, what do they talk about?” she asked. “Cricket, politics… sometimes the weather?” I mused.

Parekh smiled, “When our men sit down for dinner, they ask about the ‘paisa’.”

“Men save by reinvesting in the business,” she continued. “Women lay aside money in gold or savings certificates. But we all save because we never know what the future might bring. My kids are 32 and 27; I still stand at their doorstep on the first of the month to take a sizable portion of their income to invest [for them].”

Back at Divan’s house, the word of the day was “wastage”. My sister-in-law, having just returned from Hajj (the Muslim holy pilgrimage to Mecca) had brought prayer mats, dates and rosary beads. Divan eyed them, and immediately said there was no need for two mats. As we exchanged niceties and went on to discuss hair henna, Divan was aghast when my sister-in-law remarked that she uses three teaspoons of tea in her henna to give it a deeper colour. “Unusedtea leaves? What an absolute waste,” she exclaimed.

However, when it was time to leave, the gracious hostess did not let her guests leave empty-handed; I clutched a recycled Styrofoam cup filled with tamarind root for my cough (retrieved from the deep recesses of her freezer, as it’s much cheaper to buy in bulk). We followed Divan to the door, pushing aside tables to manoeuvre through the small space she retained after renting out the rest of the mansion.

Her final words were straight to the point: “Turn off the light before you leave the room.”

www.bbc.com

www.bbc.com

As I circled to find a parking spot, I was awestruck by the stately mansion in the upscale neighbourhood of Karachi. Casually, my sister-in-law remarked that the equally impressive estate across the road also belonged to Bilquis Sulaman Divan, the Memon (an ethnic sub-group of Sunni Muslims) and ex-colleague of hers that we were visiting. Flanked by perfectly manicured hedges, the home’s colonial architecture and sprawling, expansive gardens spoke of affluence and hinted at greater opulence within.

But on approaching, we were marched straight past the grand main entrance and guided instead to a simple room crammed with the necessities of life, including a ramshackle sewing machine by the door, threadbare sofas and an ancient refrigerator.

Although Divan and her sister – who also live with her sister’s husband and their adult daughter – have almost incalculable wealth, as owners of a bottle manufacturing plant and heiresses to their late father’s fruit-exporting company, they choose instead to spend most of their time not in the mansion’s grand rooms, but in one small living quarter. The rest of the estate has been rented out to an elite private school, which is where Divan and my sister-in-law worked for more than two decades.

Why, despite such abundance, did these people live so frugally, I wondered?

Divan and her family are not the only ones. As I would soon learn, the entire minimalist Memon community takes pride in pinching pennies.

The concentration and preservation of wealth, as the last vestiges of power and dominion that the displaced Memons clung to, has been integral to their quest for identity. And while safeguarding their security through financial stability has become second nature to the Memon diaspora, the Memons of Karachi have an especially interesting – and successful – story.

Part of what sets the Memons of Karachi apart from their Indian counterparts is the memory of the harrowing time of Partition in 1947. While the Memons who stayed in present-day India continued to have access to the established businesses and industries of their forefathers, those who uprooted their businesses and migrated had to start from scratch, setting the family’s financial status back by years, if not generations.

“My grandfather came to Pakistan, literally barefoot, asking people for work. He built his empire slowly and diversified. From childhood, we’re instilled with an awareness – and understanding – of the value of hard-earned money. It’s part of our daily narrative. It’s how we survived. And we take care to give back,” said Anila Parekh, granddaughter of the late Memon industrialist and philanthropist Ahmed Dawood.

For the Memons of Karachi, each “paisa” (Memoni for “money”, but also the Urdu word for “cent”) accumulated and saved is an ode to trials that they overcame. Although they now control the majority of many business sectors in Pakistan, including the textile industry, education sector, fertiliser industry and financial securities, respect for money is deeply engrained in Memon ethos, making for a thrifty legacy that they take pride in preserving.

“It’s not ‘don’t spend’ – it’s ‘don’t waste’,” clarified Nadeem Ghani, a Memon and dean of Academia Civitas and Nixor College, an elite school and college in Karachi. “Being frugal,” he said, “has an element of humility. It’s a manifestation of respect. We don’t shy away from placing a monetised value on our comfort.”

A Memon of Karachi would much rather make do with less or err on the side of caution than spend unnecessarily. It’s a sort of indemnification against unpredictably hard times; an homage to previous hardships.

The subsequent reverent handling of resources drives community members to cherish what they have and stretch it as far as possible. Hira Khatri, a Memon living in Karachi, told me that hand-me-downs in most Memon households typically go through multiple cycles, extending to include cousins and even closely aged uncles and aunts. Turning off the light or fan when you leave the room is important in any household, she said, but in Memon families, forgetting to do so is a cardinal offence. Memon children are taught to embrace accountability – and accounting.

“Monthly grocery money simply wasn’t for snacks; we had to pay to replenish the refrigerator out of our pocket money. We also paid for offences. Fifteen Pakistani rupees (£0.07) was the going rate for forgetting to flush the toilet or turn off the lights – this money was accumulated to pay for our internet connection,” Khatri said, recalling her family’s distinct care for overheads.

Interestingly, the Memon lifestyle closely resembles “new” guidelines governing the zero-waste movement.

“Reduce, reuse and recycle – made mainstream a couple of decades ago – has been part of the Memon tradition for centuries. It just lacked the righteous tag line,” Ghani said.

Certain themes were recurrent in many of the Memon households I visited, such as preferring to consume what is in season and locally grown, or meal planning to ensure there is no food wastage. “At dinner, we have one vegetable-based dish and one meat-based entrée – anything beyond that and I am questioned about the wastage,” Parekh said.

According to Parekh and Manahyl Ashfaq, an aspiring Memon videographer, it is a point of pride for produce to be peeled ever so thinly to reduce wastage. In fact, using vegetable peelers is considered extravagant, with a knife being used to scrape off the peel instead, if possible.

“Memons don’t suspend reality to splurge and have an aspirational moment beyond their existence,” Ghani explained over the phone.

Ghani was overseas for a week, driving cross-country through the US, taking his 18-year-old son to look at Ivy League schools. That day it was Princeton – but he unabashedly shared that he was wearing apparel from Wal-Mart: solid, reliable and good value for money. Citing Memon dining conventions as an example of frugality, he continued, “It’s less about the image we cultivate, and more about optimal usage. To us, it would be disingenuous not to use that free appetiser coupon – whether during the first date or years after marriage.”

To uninitiated outsiders, then, extravagant Memon weddings with grand marquees, 10-course menus and bridal outfits that can run upwards of 10 lakh rupees (almost £5,000), seem incongruous with their frugal ways, but essentially, the functions epitomise their regard for guests. The distinguishing feature of a Memon wedding is the guest list, which can easily run into the thousands. When asked about the paradox, Moshin Adhi, president of the Memon Professional Forum, which provides vocational training and networking opportunities to Memon youth, was quick to respond: “Weddings are great networking and branding opportunities!” Calculated? Perhaps. But also genuinely upfront.

Memon frugality may mirror the larger zero-waste movement, but their habit of earnestly and openly discussing savings and money is what sets them apart. Parekh explained it best:

“When your men sit down for dinner, what do they talk about?” she asked. “Cricket, politics… sometimes the weather?” I mused.

Parekh smiled, “When our men sit down for dinner, they ask about the ‘paisa’.”

“Men save by reinvesting in the business,” she continued. “Women lay aside money in gold or savings certificates. But we all save because we never know what the future might bring. My kids are 32 and 27; I still stand at their doorstep on the first of the month to take a sizable portion of their income to invest [for them].”

Back at Divan’s house, the word of the day was “wastage”. My sister-in-law, having just returned from Hajj (the Muslim holy pilgrimage to Mecca) had brought prayer mats, dates and rosary beads. Divan eyed them, and immediately said there was no need for two mats. As we exchanged niceties and went on to discuss hair henna, Divan was aghast when my sister-in-law remarked that she uses three teaspoons of tea in her henna to give it a deeper colour. “Unusedtea leaves? What an absolute waste,” she exclaimed.

However, when it was time to leave, the gracious hostess did not let her guests leave empty-handed; I clutched a recycled Styrofoam cup filled with tamarind root for my cough (retrieved from the deep recesses of her freezer, as it’s much cheaper to buy in bulk). We followed Divan to the door, pushing aside tables to manoeuvre through the small space she retained after renting out the rest of the mansion.

Her final words were straight to the point: “Turn off the light before you leave the room.”

Pakistan’s centuries-old ‘zero-waste’ movement

The Memon predisposition towards frugality is iconic within Pakistan, but they celebrate their stereotyping as an achievement; a tribute to their enduring prosperity and resilience.