Edison Chen

SENIOR MEMBER

- Joined

- Aug 21, 2013

- Messages

- 2,933

- Reaction score

- 11

- Country

- Location

http://online.wsj.com/articles/the-best-language-for-math-1410304008?mod=e2fb

What's the best language for learning math? Hint: You're not reading it.

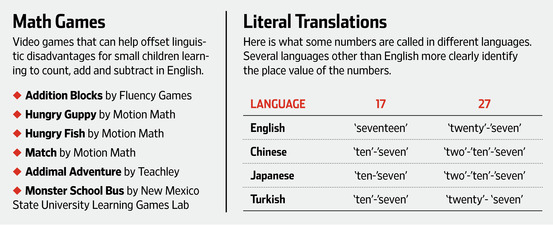

Chinese, Japanese, Korean and Turkish use simpler number words and express math concepts more clearly than English, making it easier for small children to learn counting and arithmetic, research shows.

The language gap is drawing growing attention amid a push by psychologists and educators to build numeracy in small children—the mathematical equivalent of literacy. Confusing English word names have been linked in several recent studies to weaker counting and arithmetic skills in children. However, researchers are finding some easy ways for parents to level the playing field through games and early practice.

Differences between Chinese and English, in particular, have been studied in U.S. and Chinese schools for decades by Karen Fuson, a professor emerita in the school of education and social policy at Northwestern University, and Yeping Li, an expert on Chinese math education and a professor of teaching, learning and culture at Texas A&M University. Chinese has just nine number names, while English has more than two dozen unique number words.

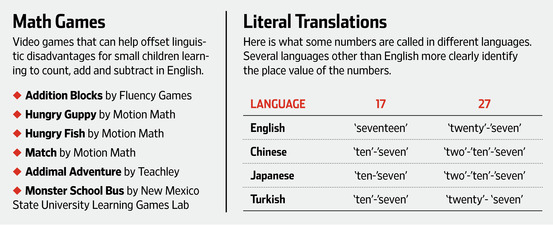

The trouble starts at "11." English has a unique word for the number, while Chinese (as well as Japanese and Korean, among other languages) have words that can be translated as "ten-one"—spoken with the "ten" first. That makes it easier to understand the place value—the value of the position of each digit in a number—as well as making it clear that the number system is based on units of 10.

English number names over 10 don't as clearly label place value, and number words for the teens, such as 17, reverse the order of the ones and "teens," making it easy for children to confuse, say, 17 with 71, the research shows. When doing multi-digit addition and subtraction, children working with English number names have a harder time understanding that two-digit numbers are made up of tens and ones, making it more difficult to avoid errors.

These may seem like small issues, but the additional mental steps needed to solve problems cause more errors and drain working memory capacity, says Dr. Fuson, author of a school math curriculum, Math Expressions, that provides added support for English-speaking students in learning place value.

It feels more natural for Chinese speakers than for English speakers to use the "make-a-ten" addition and subtraction strategy taught to first-graders in many East Asian countries. When adding two numbers, students break down the numbers into parts, or addends, and regroup them into tens and ones. For instance, 9 plus 5 becomes 9 plus 1 plus 4. The make-a-ten method is a powerful tool for mastering more advanced multi-digit addition and subtraction problems , Dr. Fuson says.

Many U.S. teachers have increased instruction in the make-a-ten method, and the Common Core standards adopted by many states call for first-graders to use it to add and subtract. First-graders' understanding of place value predicts their ability to do two-digit addition in third grade, according to a 2011 study of 94 elementary-school children in Research in Developmental Disabilities.

The U.S.-Asian math-achievement gap—a sensitive and much-studied topic—has more complicated roots than language. Chinese teachers typically spend more time explaining math concepts and getting students involved in working on difficult problems. In the home, Chinese parents tend to spend more time teaching arithmetic facts and games and using numbers in daily life, says a 2010 study in the Review of Educational Research by researchers at the Hong Kong Institute of Education and the University of Hong Kong.

When Chinese preschoolers enter kindergarten, they're ahead of their U.S. counterparts in the adding and counting skills typically taught by Chinese parents. They're also one to two years ahead on a skill their parents don't teach—placing numbers on a number line based on size, according to a 2008 study of 29 Chinese and 24 U.S. preschoolers by researchers at Carnegie Mellon University.

In math, one concept builds on another. By the time U.S. students reach high school, they rank 30th among students from 65 nations and education systems on international achievement exams, while Chinese and Korean students lead the world.

The negative impact of English is apparent in a 2014 study comparing 59 English-speaking Canadian children from Ottawa, Canada, with 88 Turkish children from Istanbul, ranging in age from 3 to 41/2 years. The Turkish children had received less instruction in numbers and counting than the Canadians. Yet the Turkish children improved their counting skills more after practicing in the lab with a numbered board game, according to the study, co-written by Jo-Anne LeFevre, director of the Institute of Cognitive Science at Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario. Turkish students learning to count in their native language "mastered it more quickly" than the children learning in English, Dr. LeFevre says.

Dr. LeFevre is among a growing group of researchers exploring how parents can help instill number skills early. Children whose parents taught them to recognize and name digits and practice simple addition problems tended to do well on such kindergarten tasks as counting and comparing numbers, says a 2014 study of 183 children and their parents in the Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, co-written by Dr. LeFevre.

Board games can offset some of the disadvantages of speaking English, though only if played in a specific way. Some kindergartners who played a board game with the numbers 1 through 100 lined up in straight rows of 10 improved their performance at identifying numbers and placing numbers on a number line, according to a 2014 study led by Elida Laski, an assistant professor of applied and developmental psychology at Boston College. The rows of 10 helped children see that the number system is based on tens.

But the children improved only if researchers had them count aloud starting with the number of the square where they had landed; if children landed on square 5 and spun a 2, for example, they would count, "6, 7." This skill, called "counting on," is useful in early arithmetic. Kids who counted starting with "1" for every turn improved their performance only half as much.

Games such as "Chutes and Ladders" can have the same effect if children count on with each turn, Dr. Laski says. Studies show games without numbers in the squares, or set up in a winding or circular pattern, such as Candy Land, don't provide the same benefits.

Just drawing a board game on paper or cardboard and playing it with a preschooler a few times can firm up counting skills. "It's definitely more fun than doing a work sheet, and just as valuable," Dr. Laski says.

Children whose parents exposed them to number games and showed they enjoyed playing with numbers tended to have better skills, according to the 2014 study co-written by Dr. LeFevre.

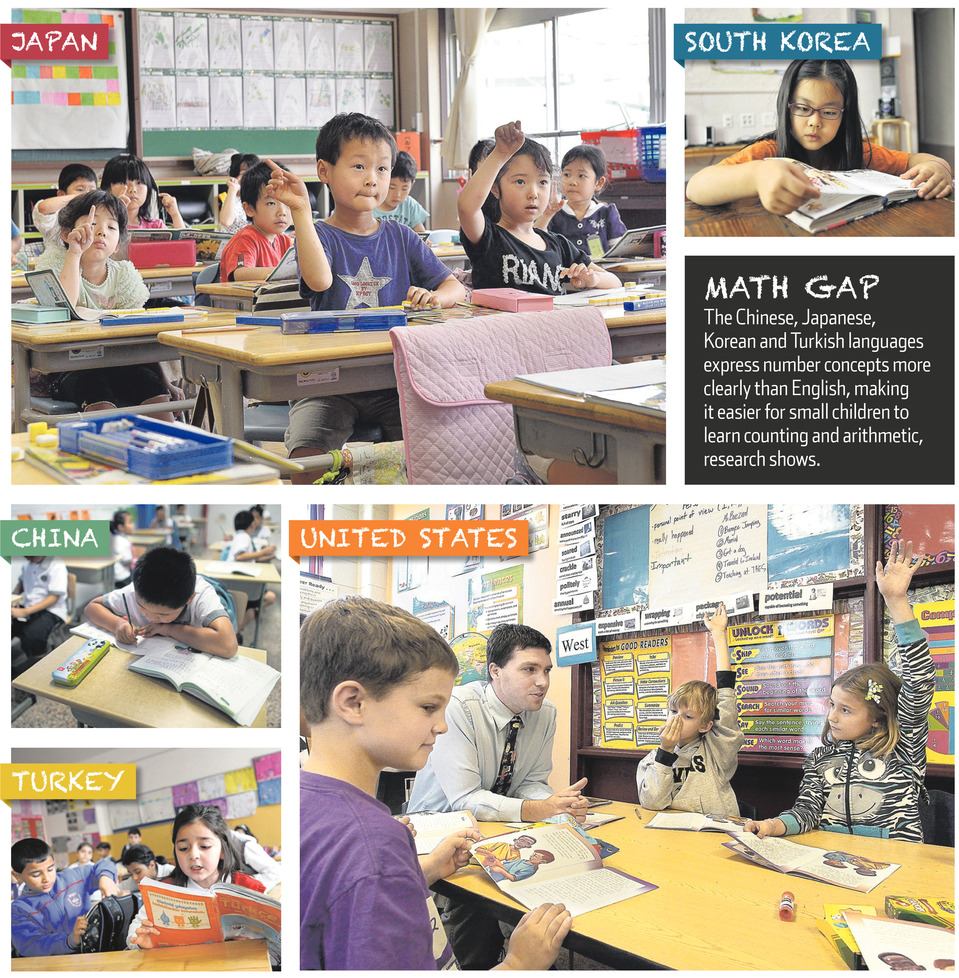

Math teacher Andrew Stadel wants to pass on his interest in math to his 4-year-old son Patrick. A videogame, "Hungry Guppy" by Motion Math, based in San Francisco, drew Patrick's attention at age 2; players drag together bubbles with dots to add them, then feed them to a fish. He is now playing its successor for older kids, "Hungry Fish." Patrick is "curious about what numbers will pair up to make the desired sum," and if he makes a mistake, "there's not a huge penalty and it's not deflating to him," Mr. Stadel says.

Such videogames build fluency in doing calculations, freeing mental energy for learning. A game called "Addimal Adventures" by Teachley teaches different strategies for addition, showing "there's more than one way to solve a problem," says Allisyn Levy, vice president of an educational digital-game line, GameUp, offered by BrainPOP, New York City, a creator of animated educational content.

Ten-year-old Luke Sullivan of Marietta, Ga., says a game called "Addition Blocks" by Fluency Games of Smyrna, Ga., helped him learn when he started playing it two years ago. "You realize it's educational, but then you start to enjoy it," Luke says.

What's the best language for learning math? Hint: You're not reading it.

Chinese, Japanese, Korean and Turkish use simpler number words and express math concepts more clearly than English, making it easier for small children to learn counting and arithmetic, research shows.

The language gap is drawing growing attention amid a push by psychologists and educators to build numeracy in small children—the mathematical equivalent of literacy. Confusing English word names have been linked in several recent studies to weaker counting and arithmetic skills in children. However, researchers are finding some easy ways for parents to level the playing field through games and early practice.

Differences between Chinese and English, in particular, have been studied in U.S. and Chinese schools for decades by Karen Fuson, a professor emerita in the school of education and social policy at Northwestern University, and Yeping Li, an expert on Chinese math education and a professor of teaching, learning and culture at Texas A&M University. Chinese has just nine number names, while English has more than two dozen unique number words.

The trouble starts at "11." English has a unique word for the number, while Chinese (as well as Japanese and Korean, among other languages) have words that can be translated as "ten-one"—spoken with the "ten" first. That makes it easier to understand the place value—the value of the position of each digit in a number—as well as making it clear that the number system is based on units of 10.

English number names over 10 don't as clearly label place value, and number words for the teens, such as 17, reverse the order of the ones and "teens," making it easy for children to confuse, say, 17 with 71, the research shows. When doing multi-digit addition and subtraction, children working with English number names have a harder time understanding that two-digit numbers are made up of tens and ones, making it more difficult to avoid errors.

These may seem like small issues, but the additional mental steps needed to solve problems cause more errors and drain working memory capacity, says Dr. Fuson, author of a school math curriculum, Math Expressions, that provides added support for English-speaking students in learning place value.

It feels more natural for Chinese speakers than for English speakers to use the "make-a-ten" addition and subtraction strategy taught to first-graders in many East Asian countries. When adding two numbers, students break down the numbers into parts, or addends, and regroup them into tens and ones. For instance, 9 plus 5 becomes 9 plus 1 plus 4. The make-a-ten method is a powerful tool for mastering more advanced multi-digit addition and subtraction problems , Dr. Fuson says.

Many U.S. teachers have increased instruction in the make-a-ten method, and the Common Core standards adopted by many states call for first-graders to use it to add and subtract. First-graders' understanding of place value predicts their ability to do two-digit addition in third grade, according to a 2011 study of 94 elementary-school children in Research in Developmental Disabilities.

The U.S.-Asian math-achievement gap—a sensitive and much-studied topic—has more complicated roots than language. Chinese teachers typically spend more time explaining math concepts and getting students involved in working on difficult problems. In the home, Chinese parents tend to spend more time teaching arithmetic facts and games and using numbers in daily life, says a 2010 study in the Review of Educational Research by researchers at the Hong Kong Institute of Education and the University of Hong Kong.

When Chinese preschoolers enter kindergarten, they're ahead of their U.S. counterparts in the adding and counting skills typically taught by Chinese parents. They're also one to two years ahead on a skill their parents don't teach—placing numbers on a number line based on size, according to a 2008 study of 29 Chinese and 24 U.S. preschoolers by researchers at Carnegie Mellon University.

In math, one concept builds on another. By the time U.S. students reach high school, they rank 30th among students from 65 nations and education systems on international achievement exams, while Chinese and Korean students lead the world.

The negative impact of English is apparent in a 2014 study comparing 59 English-speaking Canadian children from Ottawa, Canada, with 88 Turkish children from Istanbul, ranging in age from 3 to 41/2 years. The Turkish children had received less instruction in numbers and counting than the Canadians. Yet the Turkish children improved their counting skills more after practicing in the lab with a numbered board game, according to the study, co-written by Jo-Anne LeFevre, director of the Institute of Cognitive Science at Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario. Turkish students learning to count in their native language "mastered it more quickly" than the children learning in English, Dr. LeFevre says.

Dr. LeFevre is among a growing group of researchers exploring how parents can help instill number skills early. Children whose parents taught them to recognize and name digits and practice simple addition problems tended to do well on such kindergarten tasks as counting and comparing numbers, says a 2014 study of 183 children and their parents in the Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, co-written by Dr. LeFevre.

Board games can offset some of the disadvantages of speaking English, though only if played in a specific way. Some kindergartners who played a board game with the numbers 1 through 100 lined up in straight rows of 10 improved their performance at identifying numbers and placing numbers on a number line, according to a 2014 study led by Elida Laski, an assistant professor of applied and developmental psychology at Boston College. The rows of 10 helped children see that the number system is based on tens.

But the children improved only if researchers had them count aloud starting with the number of the square where they had landed; if children landed on square 5 and spun a 2, for example, they would count, "6, 7." This skill, called "counting on," is useful in early arithmetic. Kids who counted starting with "1" for every turn improved their performance only half as much.

Games such as "Chutes and Ladders" can have the same effect if children count on with each turn, Dr. Laski says. Studies show games without numbers in the squares, or set up in a winding or circular pattern, such as Candy Land, don't provide the same benefits.

Just drawing a board game on paper or cardboard and playing it with a preschooler a few times can firm up counting skills. "It's definitely more fun than doing a work sheet, and just as valuable," Dr. Laski says.

Children whose parents exposed them to number games and showed they enjoyed playing with numbers tended to have better skills, according to the 2014 study co-written by Dr. LeFevre.

Math teacher Andrew Stadel wants to pass on his interest in math to his 4-year-old son Patrick. A videogame, "Hungry Guppy" by Motion Math, based in San Francisco, drew Patrick's attention at age 2; players drag together bubbles with dots to add them, then feed them to a fish. He is now playing its successor for older kids, "Hungry Fish." Patrick is "curious about what numbers will pair up to make the desired sum," and if he makes a mistake, "there's not a huge penalty and it's not deflating to him," Mr. Stadel says.

Such videogames build fluency in doing calculations, freeing mental energy for learning. A game called "Addimal Adventures" by Teachley teaches different strategies for addition, showing "there's more than one way to solve a problem," says Allisyn Levy, vice president of an educational digital-game line, GameUp, offered by BrainPOP, New York City, a creator of animated educational content.

Ten-year-old Luke Sullivan of Marietta, Ga., says a game called "Addition Blocks" by Fluency Games of Smyrna, Ga., helped him learn when he started playing it two years ago. "You realize it's educational, but then you start to enjoy it," Luke says.