ghazi52

PDF THINK TANK: ANALYST

- Joined

- Mar 21, 2007

- Messages

- 101,794

- Reaction score

- 106

- Country

- Location

Orange Farming in Pakistan

A Survey of Pakistan Citrus Industry

By Muhammad Imran Siddique and Elena Garnevska

Abstract

Pakistan is producing more than 30 types of different fruits of which citrus fruit is leading among all fruit and constitutes about 30% of total fruit production in the country. Above 90% of citrus fruits are produced in Punjab province and distributed through different value chains in domestic as well as in international markets.

A large part of citrus fruit produced in Pakistan is mostly consumed locally without much value addition; however, 10–12% of total production is exported after value addition. The value chains are very diverse, and a number of different players actively participate in these chains, which ultimately decide the destination of citrus fruit in these supply chain(s). Knowing all these facts, the main aim of this research is to identify different value chains of citrus fruit (Kinnow) in Pakistan and also to identify and discuss the role and function of different value chain players in the citrus industry in Pakistan.

A survey involving of different players of Pakistan’s citrus industry was conducted in 2013–2014 to better understand the citrus value chain(s). Using a convenience sampling technique, a total of 245 respondents were interviewed during a period of 4–5 months from three leading citrus-producing districts.

It was found that citrus value chains can be classified into two major types: unprocessed citrus value chain and processed citrus value chains. It was also found that in the past, a large number of citrus growers were involved in preharvest contracting for their orchards and only a small number of citrus growers sold their orchards directly into local and foreign markets. The proportion has been gradually changed now and growers are becoming progressive and more market oriented.

1. Pakistan citrus industry

The agriculture sector plays a pivotal role in Pakistan’s economy and it holds the key to prosperity. A number of agricultural resources, fertile land, well-irrigated plains and variety of seasons are favourable for the Pakistan agricultural industry. Despite the decline in the share of agriculture in gross domestic production (GDP), nearly two-thirds of the population still depend on this sector for their livelihood [1]. Agriculture is considered as one of the major drivers of economic growth in the country. It has been estimated that in 2014–2015, the total production of agriculture crops was 116 million tonnes. Pakistan produces about 13.5 million tonnes of fruit and vegetables annually. In 2014–2015, the total fruit production was recorded at 7.01 million tonnes, which composed of 48.3% of the total fruit and vegetables production in the country [2, 3].

1.1. Citrus production

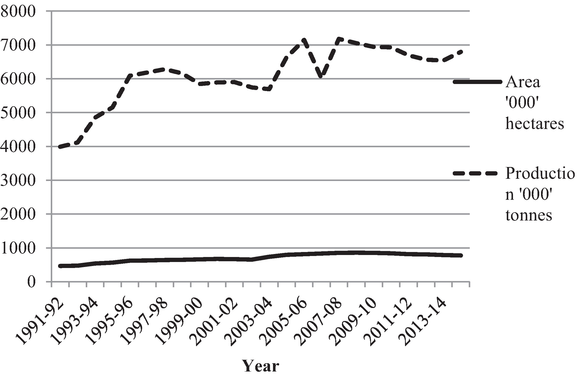

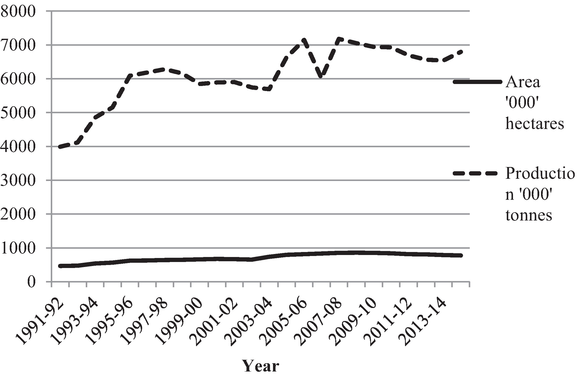

The overall trend for all fruit production in Pakistan is increasing except for the year 2006–2007, when a great decrease of production of all fruits as well as citrus fruits was observed due to unfavourable weather (hailstorm) and water shortage, as shown in Figure 1. The area under all fruits and production both has been increasing gradually. Citrus fruit is prominent in terms of its production followed by mango, dates and guava. The total citrus production was 2.4 million tonnes in 2014–2015 that constitutes 35.2% of total fruit production) [3]. Citrus fruit includes mandarins (Kinnow), oranges, grapefruit, lemons and limes, of which mandarin (Kinnow) is of significant importance to Pakistan.

Figure 1.

Area and production of all fruit in Pakistan. Source: [3, 5, 6].

Pakistan’s total production of citrus fruit (primarily Kinnow) is approximately 2.0 million metric tonnes annually. Although there is no remarkable increase in area under citrus production, the production has increased up to 30.8% since 1991–1992. In 1991–1992, Pakistan produced 1.62 million tonnes citrus, which increased to 2.1 million tonnes in 2008–2009 and 2.4 million tonnes in 2014–2015 [3].

The production of citrus fruit has been increasing since 1993–1994; however, it started to decline in 1999. The citrus fruit crop requires a critical low temperature for its ripening which if not achieved may lead to decline in the production of fruit [4]. Therefore, one of the reasons of varied citrus fruit production might be due to the temperature variations in the citrus growing areas of Pakistan.

Such a great variation in temperature was recorded in 2006–2007 in citrus-producing areas due to which citrus production dropped from 2.4 to 1.4 million tonnes; however, the area under citrus fruit orchards remained the same [3].

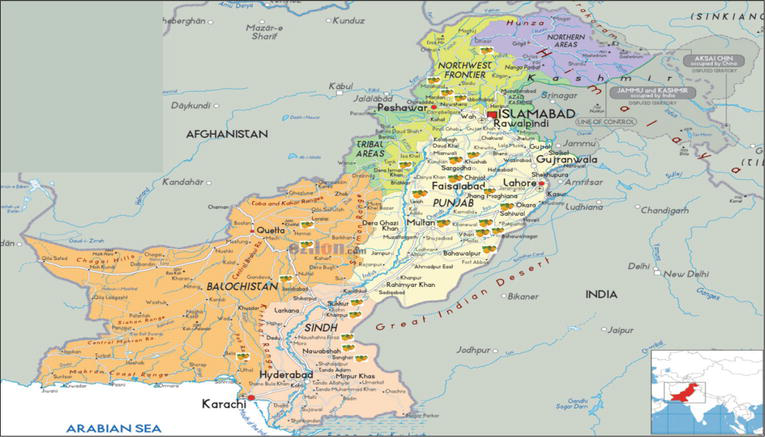

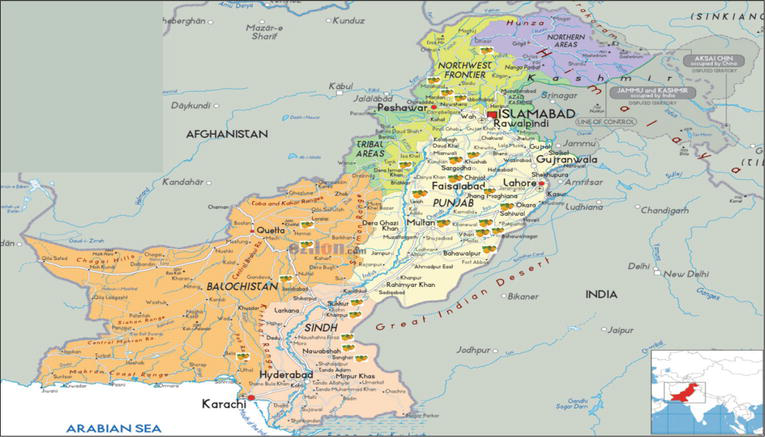

In Pakistan, citrus fruit has been predominantly cultivated in four provinces, namely: Punjab, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK), Sindh and Baluchistan. Among all four provinces, Punjab is considered to be the hub of citrus production. Table 1 represents the major citrus growing districts in all the four provinces of the country.

Table 1.

Major citrus growing areas in Pakistan.

Punjab province, according to Pakistan Horticulture Development and Export Company (PHDEC) (2005), produces more than 90% of total Kinnow production whereas KPK mainly produces oranges among all citrus fruits in the country. Sargodha, Toba Tek Singh and Mandi Bahauddin are three known districts for their citrus production in Punjab province. Different varieties of citrus fruits are also grown in small proportions in other districts.

Mandarins (Feutrell’s Early and Kinnow) and sweet orange (Mausami or Musambi and Red Blood) are very important among all the citrus varieties cultivated in Pakistan. Table 2 shows different varieties of citrus produced in the country. Punjab province, being the hub of citrus production (Kinnow), produced 97.1% of citrus fruit (Kinnow) in 2014–2015 [3].

Table 2.

Varieties of citrus fruit in Pakistan.

In Punjab province, three districts, Sargodha, Toba Tek Singh and Mandi Bahauddin, constitute around 55% of the total area under citrus cultivation and produce nearly 62% of citrus fruit [6]. In Sargodha district, Bhalwal produces 650,000 metric tonnes of Kinnow annually and is considered as the centre of Kinnow (mandarin) production (Pakistan Horticulture Development & Export Company (PHDEC), 2005). Figure 2 demonstrates citrus fruit production in four provinces of Pakistan.

Figure 2.

Province-wise production of citrus fruit in Pakistan.

In 2014–2015, the total citrus production in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) was 1.29%, in Sindh 1.26% and in Baluchistan it was 0.29%. In the late 1990s, the production of citrus fruit in the Baluchistan province increased and it was due to the increase in the area under citrus cultivation and hence production under citrus fruit was increased in Baluchistan in the late 1990s [3, 6, 9].

In Punjab province, Kinnow production was 1.80 million tonnes followed by oranges, which was about 94 thousand tonnes in 2009–2010 among different varieties of citrus fruits. In Punjab, Kinnow was 87.1% of the total citrus production and 80.3% of the total area under citrus cultivation. Oranges come next to Kinnow in production and area under cultivation and constitutes 4.5% of the total citrus production and 6% of the total area under citrus cultivation in Punjab. Grapefruit production is the lowest and it was only 3 thousand tonnes. Different types of citrus grown in Punjab province in 2009–2010 are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Production of different types of citrus fruit in Punjab.

1.2. Citrus consumption

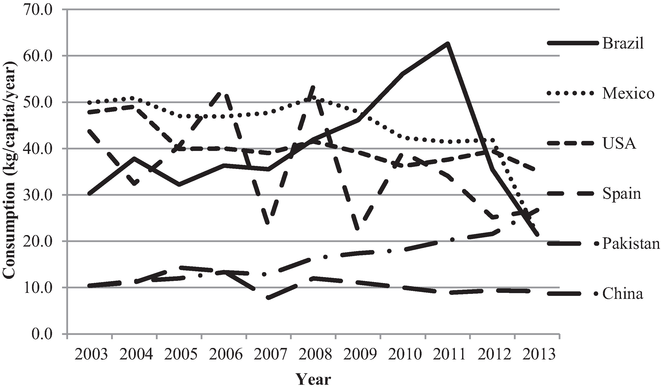

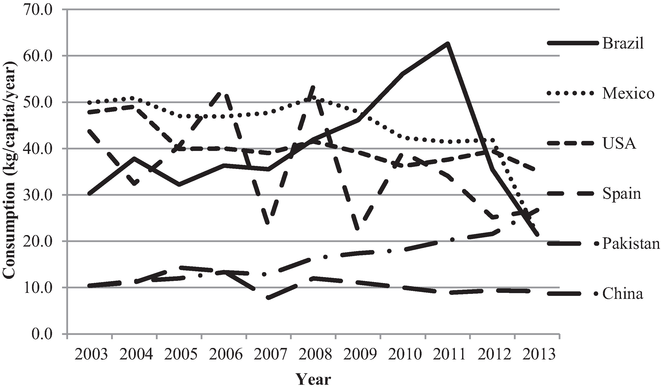

The consumption of fresh citrus fruit in developing countries has been increasing; however, it is still low compared to the developed countries. In Pakistan, per capita consumption of citrus fruit is almost static since 1999 except in 2007 when it dropped to 7.8 from 13.5 kg, as shown in Figure 3. The rapid increase in the population may be one of the major factors keeping the consumption level nearly constant despite the increase in citrus production from 1.8 million tonnes in 1999 to 2.1 million tonnes in 2009. Per capita income has increased from US$450 in 1999 to US$917 in 2009 [11].

However, the sharp decline in per capita consumption in 2007 was a result of lowest production of 1.4 million tonnes from 2.4 million tonnes in 2006, which resulted in lower domestic supply and availability of citrus fruit in the country. The high peak of 2005 in Figure 3 reflects the highest per capita consumption of citrus fruit due to decreased exports of the citrus fruit from 151.3 thousand tonnes in 2004 to 79.2 thousand tonnes in 2005.

Figure 3.

World citrus fruit consumption trend.

Figure 3 shows the annual per capita consumption (kg) of fresh citrus fruit in important countries. There was an increase in per capita consumption in Brazil that reached to the highest level in 2011 and then dropped very sharply in 2012 and 2013.

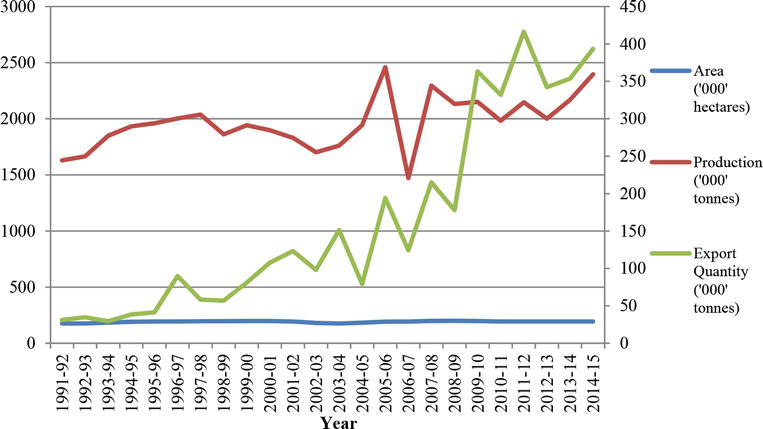

1.3. Citrus exports

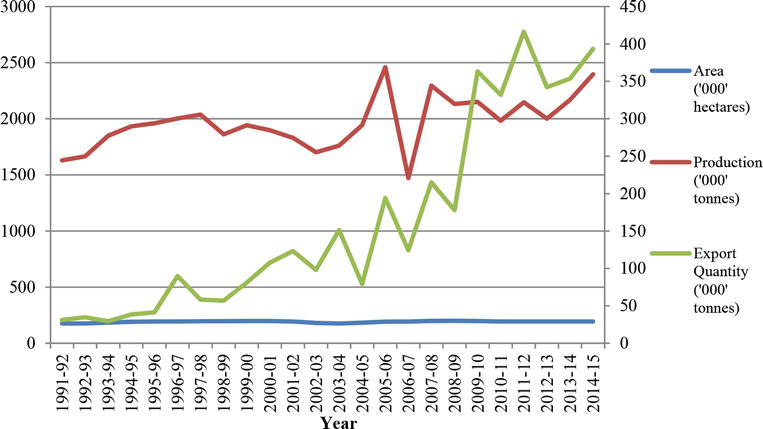

With the changing consumer preferences towards consumption of fresh and convenience food, the global demand for fresh fruit is increasing [8, 13]. Pakistan is one of the largest citrus producing countries and ranked 13th in the production of citrus fruit [5]. It has been observed that fresh citrus exports from Pakistan have been increasing since 1995–1996 as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Pakistan citrus area, production and exports.

Among all citrus fruits, Kinnow mandarin constitutes about 97% in the total exports of citrus fruit from the country [8, 14]. In 2014–2015, the total exports of citrus fruit from Pakistan were 393 thousand tonnes, which account for a total value of $204 million that represents about 16.4% of the total citrus production. As compared to 2000–2001, the total exports of citrus were exactly threefold in 2009–2010 which accounted for $99.4 million of foreign revenue. Despite the increase in production, only a small amount of citrus fruit (8–12%) is being exported.

The majority of the farmers in Pakistan own and cultivate a small size of agricultural land of less than 2 hectare. However, in Punjab, average citrus farm size was 12.3 hectare, which is considered relatively large compared to other crops [15]. The size of citrus orchard ranges from less than 1 hectare to as big as 65 hectare in different regions of the country. A few large citrus growers do exist; however, small and medium size growers are the majority [16].

The agricultural value chains in Pakistan are very diverse and start with citrus growers/producers. Like other fruits, citrus fruit value chain is primarily controlled by the private sector.

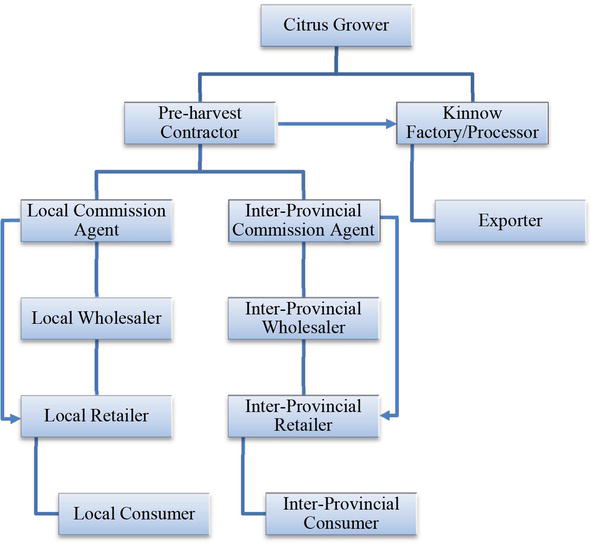

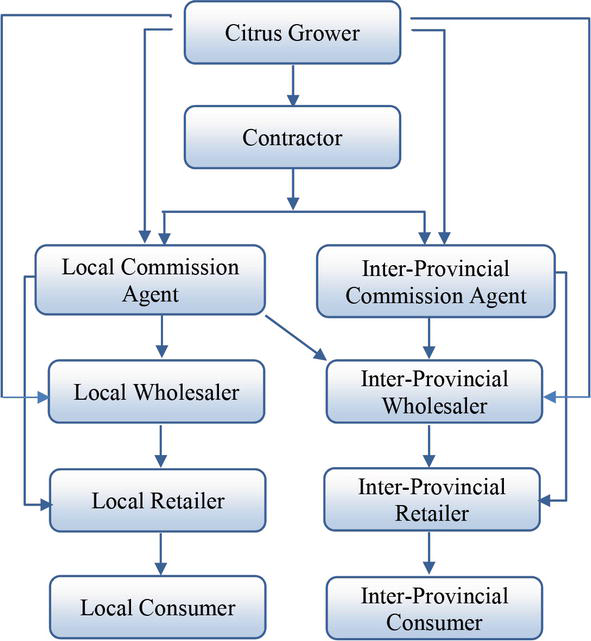

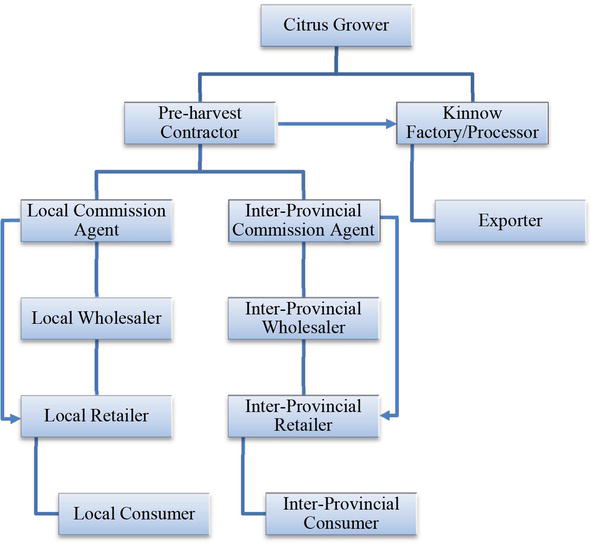

However, Government plays a facilitative role by providing basic infrastructure and regulatory measures for easy business transactions. It is generally observed that marketing intermediaries exploit agricultural crop producers by charging high margin on their investment [16]. Citrus fruit value chain(s) starts with the involvement of pre-harvest contractor directly with citrus growers. According to Chaudry [15], the typical citrus value chains in Pakistan are shown in Figure 5. The role of each player in the citrus value chain is presented later in the results and discussion sections.

Figure 5.

Value chains of citrus in Pakistan.

All the players involved in these value chains execute their usual functions as they do in other food value chains; however, the pre-harvest contractors are the most important powerful player in Pakistan citrus value chains [15, 16].

Keeping in mind the increase in production, constant domestic consumption and available surplus of citrus fruit for export, a number of questions arises; how many different citrus value chains operate in the country? Who are the players involved in the citrus value chains? Despite the availability of citrus fruit, why only a small amount of citrus fruit is being exported? To answer these questions, this study aims to identify and analyse different value chains of citrus fruit (Kinnow) that are operating in Pakistan and also to identify and discuss the role and functions of each value chain players in the citrus industry in Pakistan. Furthermore, this study identifies future opportunities and challenges of citrus sector in Pakistan.

2. Method

Both qualitative (exploratory) and quantitative (descriptive and inferential) research methods were used for this study depending upon the research questions. A survey involving different players of Pakistan’s citrus industry was conducted in 2013–2014 using semi-structured interviews assisted by a questionnaire. Primary data were collected through surveys, while secondary data were obtained from published documents, reports, journals and government publications of various public and private institutions and departments.

Using a convenience sampling technique, a total of 245 respondents were interviewed during a period of 4–5 months from three leading citrus producing districts, namely Sargodha, Toba Tek Singh and Mandi Bahauddin. The respondents included were 126 citrus growers, 99 pre-harvest contractors and 20 processing factories/exporters from these three districts. Due to unavailability of population size (sampling frame), time and budget constraint, a convenient sampling technique was used for the selection of the respondents.

The underlying reason of interviewing different players in the citrus value chains was to study closely their functions and participation in different existing value chains. It also helped identifying and understanding different value chains operating in the country. This study also identified future opportunities and challenges of citrus sector in Pakistan.

A statistical package Predictive Analytics Software–version 21 (PASW-21), previously known as Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS), was used to analyse the collected data. Fisher’s exact test was used to test the significance of different demographic variables and the selection of the value chain particularly involving pre-harvest contractor.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Citrus (Kinnow) value chain systems

The results of this study revealed that citrus (Kinnow) value chains can be classified into two major types: unprocessed citrus (Kinnow) value chain and processed citrus (Kinnow) value chain. The description of these value chains is presented in the next section.

3.1.1. Unprocessed citrus (Kinnow) value chain

Unprocessed citrus (Kinnow) graded and packed before selling to the local market and does not include usually washing and waxing. Figure 6 presents the unprocessed citrus (Kinnow) value chain in the country.

Figure 6.

Unprocessed citrus (Kinnow) value chain for local market.

About 50–60% Kinnow is marketed in the country for domestic consumption while nearly 30% Kinnow is accounted for post-harvest losses [8]. Citrus growers, pre-harvest contractors, local (provincial) commission agents, inter-provincial commission agents, local wholesalers, inter-provincial wholesalers, local and inter-provincial retailers are different actors of unprocessed citrus (Kinnow) value chain in Pakistan.

The major players of the unprocessed citrus (Kinnow) value chain are citrus growers and pre-harvest contractors and their marketing strategies intensely affect the citrus supply chain in the country. It was common practice in the past where about 90% of the citrus growers used to sell their orchard to pre-harvest contractors.

The predominate reasons include unavailability of finances, lack of market information, ease of the transaction, avoiding the future price fluctuations and norms of the business [15]. Citrus growers are becoming more market oriented and adapting different marketing channels to get high price for their products instead of selling solely to pre-harvest contractors. The improved education level, government support and technological developments are the reasons for this change. One of the citrus growers replied when asked about direct marketing of his fruit in the market:

‘Now nearly every citrus grower has an access to prices of different local and provincial markets which has helped us to involve ourselves into direct marketing of our fruit. Being ignorant of different market prices in the past, we were unable to decide where to sell, hence carried out with the pre-harvest contractor. Thanks for the government support, who provided us this opportunity to market our produce directly and earn good profit’.

3.1.2. Processed citrus (Kinnow) value chain

Kinnow processing is of two types: (1) for export and involves washing, waxing, grading and packing and (2) for juice extraction.

3.1.2.1. Processed citrus (Kinnow) value chain for export

Only 8–12% Kinnow is processed for export to different countries. In 2013–2014, the major exports of Kinnow mandarin were to Afghanistan (113,000 tonnes), Russian Federation (72,000 tonnes) and United Arab Emirates (68,000 tonnes). A complete list of countries is attached in Appendix A [17].

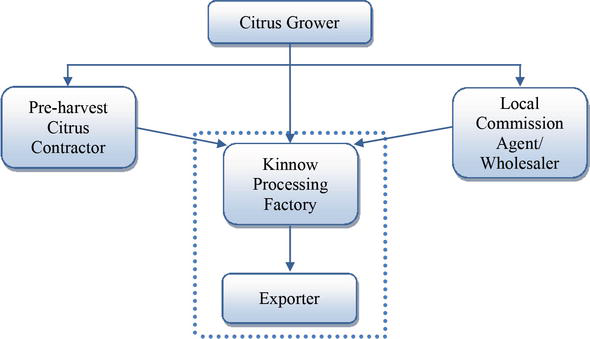

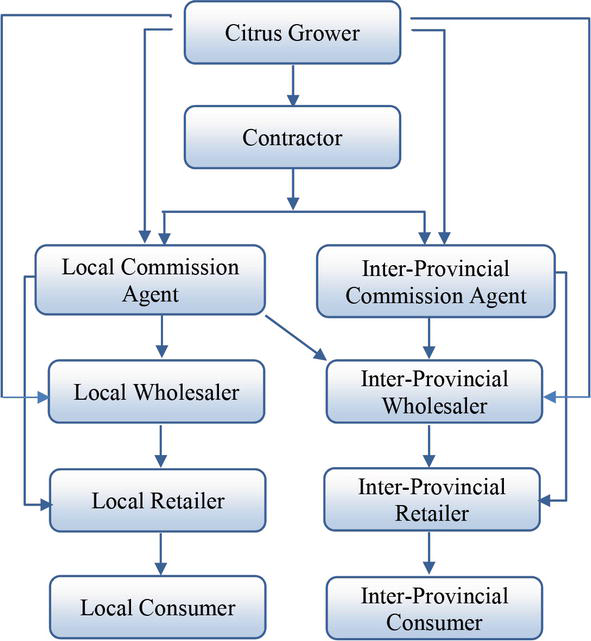

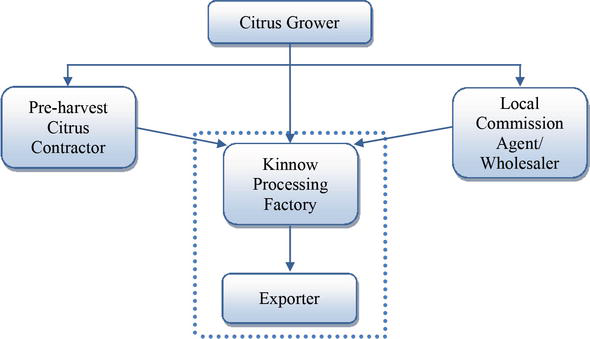

Processed citrus (Kinnow) value chain comprises citrus growers, pre-harvest contractors, local commission agents/wholesalers, Kinnow processing factories and exporters (Figure 7). The processed citrus value chain and unprocessed citrus value chain are nearly similar except Kinnow processing factory, and exporters are involved in processed value chain at the end stage of the process.

Figure 7.

Processed citrus (Kinnow) value chain for export.

Citrus growers, pre-harvest contractors and commission agents sell citrus fruit directly to factories (Kinnow processing) and exporters. Pre-harvest contractors and some commission agents act on behalf of these Kinnow processors and exporters and purchase citrus fruit for them. These agents are provided with some credit or advance payments to buy citrus fruit. A good family and financial background, market reputation and ability of constant supply of fruit in the season are the qualities of sellers preferred by these Kinnow processors and exporters. Sellers to processors and exporters are paid through cheques. One of the exporters commented on the selection of seller (grower/contractor/commission agent/wholesaler):

‘In our export business, we need to make promises with our importers for certain quantity of fruit in the season; therefore, all exporters try to deal with the seller who can commit constant supply of citrus. A well reputed, financially strong with good moral character seller is our first choice to deal with’.

In Sargodha, about 150 Kinnow processing factories are functioning but only 25–30 processing factories are exporting citrus to different countries. The reasons of such a low export from the country include high demand for seedless Kinnow (hybrid mandarin) in the developed countries (not produced in Pakistan), marketing practices and failure to meet the quality certification standards. One of the respondents who wanted to export to European countries commented:

‘I always take good care of my orchards; hence, I manage to get good quality fruit in each season. Realising the quality, I decided to export my fruit to Europe last year but I was told that I should grow citrus to meet quality certification standards required for export which I am following now. Hopefully, I would be able to export my citrus to Europe soon’.

A few processing units are also being constructed in other districts as well, for example, district Mandi Bahauddin, district Toba Tek Singh and district Multan.

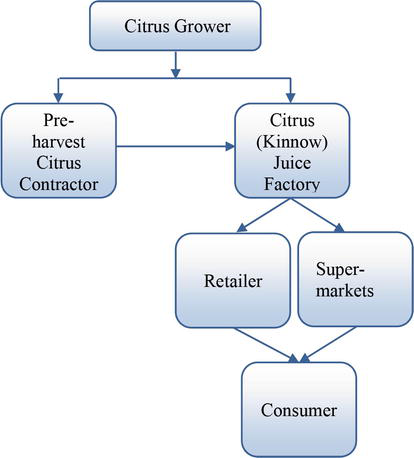

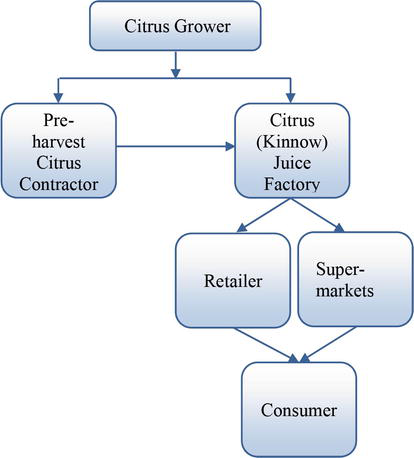

3.1.2.2. Processed citrus (Kinnow) value chain for juice extraction

A total of 52 fruit processing and juice extraction factories are operating in Pakistan [18]. Only five of them are processing citrus fruit for juice extraction. About 6% to the total citrus produced in the country is processed for juice extraction [18]. These factories are concentrated in the major citrus producing areas such as Sargodha, Bhalwal and Mateela cities. Citrus growers and pre-harvest contractors sell mostly drop off, low quality and non-marketable fruit to these juice factories, which process it into juice concentrate and sell it to different retail shops and supermarkets in the country.

One of the contractors who supply to exporters and processors replied:

‘I always try to sell exporters and processors because they pay premium price for my fruit. However, these exporters and processors only purchase selective fruit from me and leave small size, non-uniform and unripe fruit. I don’t mind it; I sell this non-selective fruit to juice factories and recover my cost. Job done’.

Figure 8 shows different functionaries of processed citrus (Kinnow) value chain.

Figure 8.

Processed citrus (Kinnow) value chain for juice extraction.

3.2. Description of different value chain players

Different players of citrus (Kinnow) value chain including citrus growers, pre-harvest contractors, commission agents, wholesalers and retailers are described and discussed below.

3.2.1. Citrus growers

The results of this study revealed that majority of the citrus growers (76.2%) were 31–60 years of age and only 6.3% were quite young (under 25 years old) in the citrus industry. However, about 17% citrus growers were above 60 years of age. The literacy rate was more than 90% in the citrus growers (having at least 5 years of schooling) and only 3.2% respondents were illiterate. It was reported that the literacy rate was increasing in the citrus growing areas in Pakistan, thus providing basis for the growth of citrus growers and making them more market oriented [19]. The results also showed that nearly 80% of the citrus growers were very experienced and were involved in the citrus industry for many years.

The size of the citrus orchards was small, and majority of the citrus growers possessed less than 20 acres (Table 4).

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics for citrus growers.

The size of these citrus orchards was further reduced when the orchard was divided among the next generations. Previously, it was found that majority of the citrus growers (more than 90%) preferred to market their produce through pre-harvest contractors, thus reducing the direct involvement of the citrus growers in the value chains. Due to better government policies in the education sector and increasing market awareness, the level of literacy rate has increased in the last 10 years.

All citrus growers were educated and became aware of market information and opportunities. As citrus growers are becoming more market oriented, they are searching for reliable market information to find alternative value chains other than selling directly to pre-harvest contractors. According to this study, about 46% of the citrus growers are selling their orchard to pre-harvest contractors. This finding is contrary to the previous study conducted by Chaudry [15] and Ali [16] who reported that 95% of citrus growers sold their orchards to pre-harvest contractors about 15 years ago.

Nearly 30% of the citrus growers in the sample sold their orchard to commission agents/wholesalers or exporters. Price was settled on commission basis at a rate of 7–8% of the total sale price of the produce with the commission agent or wholesaler. Exporters and processing factories usually announce citrus fruit purchase price per 40 kg for the season. It is negotiable in certain cases, for example, if citrus grower(s) contract for complete season fruit supply.

There is no government control over prices of Kinnow and it is determined by market forces (demand and supply). The only problem while selling to exporter was that it only purchased good quality fruit with good size and colour (selective fruit purchase). This was one of the reasons, citrus growers switch to alternative buyers who purchase and pay the price for the whole produce. Nearly 6% citrus growers sold their produce to different buyers instead of selling to only one buyer.

3.2.2. Citrus pre-harvest contractors

A total of 99 pre-harvest contractors were interviewed for the study. About 70% pre-harvest contractors had US$0.1–$0.5 million business volume and were considered medium-sized contractors. Pre-harvest contractors either used their own money to buy the orchards or acted as an agent on the behalf of the other actors of the citrus supply chain, for example, commission agents, wholesalers, processors or exporters. The results revealed that majority of the pre-harvest contractors (80% of the respondents) had more than 10 years of experience, as shown in Table 5. However, small pre-harvest contractors had less than 10 years of experience due to the fact that they work seasonally in the market and were not a regular player of citrus supply chain in the country.

Majority of the citrus growers were well educated and experienced businessmen, whereas, only 35% pre-harvest contractors were illiterate (not even 2 years at school) but they work with either well-educated business partners or family members (brother, son).

Table 5.

Citrus pre-harvest contractors general information.

About 50% of the pre-harvest contractors sold their fruit to commission agents or wholesalers, as shown in Table 5. Price is paid on commission basis at a rate of 7–8% of the total sale price of the produce. Usually, there was 1-year contract (written or verbal) between pre-harvest contractors and commission agents or wholesalers to supply a certain quantity of fruit under the contract on a fix price. Nearly 40% of the pre-harvest contractors sold their fruit directly to exporters. Usually, price was announced by processors and exporter association; however, in some cases it was negotiable.

Citrus growers sold their orchards in advance to contractors for different reasons. Firstly, citrus growers in Pakistan were not financially sound enough to market their produce. Secondly, responsibility of looking after the orchard is shared between farmers and pre-harvest contractors, and lessen farmer’s financial burden for fertiliser and pesticides which is now provided by the pre-harvest contractors. On the other hand, pre-harvest contractor took control over the produce and bargaining power for selling the fruit in the market. One of the citrus growers commented on pre-harvest sale of his orchard:

‘It is always a problem for me to buy inputs once my orchard starts flowering. Pre-harvest contractor, on one hand, purchase my orchard well in time and on the other hand, help in providing me the required inputs which otherwise I cannot afford’.

3.2.2.1. Types of contractors

There are different types of citrus orchard contractors operating in the country. They can be divided into three broad categories on the basis of their purchasing power of citrus fruit for trading purposes.

3.2.3. Descriptions of the other players involved in Pakistan citrus value chains

4. Opportunities and challenges for Pakistan citrus industry

Citrus growers are becoming more market oriented; therefore, by increasing the market-led opportunities like crop management, improving quality of the fruit, adding more value through processing will develop and expand Pakistan citrus industry. With newly developed infrastructure and transportation systems, domestic as well as international supply chain of citrus industry will be better established towards becoming more efficient and reducing the overall waste.

The exports of citrus fruit from the country are only 8–12% of the total production; therefore, there lies a great opportunity and potential in the export of citrus fruit. By developing the quality management practices, improving supply chains, establishing certification scheme and reducing post-harvest losses, the exports can be increased particularly in the European countries, Middle East, South East Asia, China and Central Asia markets.

The challenges that Pakistan citrus industry is facing include, but not limited to, agro-ecological climate with extreme summer temperatures, frost in winter and water scarcity/shortage.

Inefficient production, irrigation methods, post-harvest losses, low grade fruit, poor disease control, lack of fertilizers/manures in the soil and inefficient supply chains are the other major challenges in citrus value chains. To overcome these challenges, citrus grower association (private entity owned by growers) is working closely with government departments and institutions to provide required inputs and expertise to growers that can raise the quantity and quality of fruit.

The lack of skilled and trained labour for fruit picking poses another marketing constraint, which in turn affects the quality of picked fruit. Even the lack of seasonal or temporary labour for fruit picking is also a challenge. The efforts are being made by extension workers, medium and large citrus growers to provide necessary training and accommodation facilities to the labour. This will not only decrease the fruit damage during picking but also ensure the availability of the labour when required.

Good agricultural practices (GAPs) and sanitary phytosanitary (SPS) measures are required for markets such as Europe, the USA and Oceania. However, efforts are being made, both publicly and privately, to uplift the quality of citrus fruit in order to get required certification for export.

5. Conclusion

The agro-food value chain system in Pakistan is very diverse and nearly all citrus value chains are dominated by citrus growers, pre-harvest contractors and exporters of citrus fruit with the involvement of other value chain members like commission agents, wholesalers, and retailers.

It was found that citrus value chains can be classified into two major types : unprocessed citrus value chain for local markets and processed citrus value chains for export and juice extraction. In Pakistan, the majority of citrus orchards are less than a hectare; however, the average size of citrus orchard is almost 20 hectare. In the past, mostly citrus growers sold their fruit or orchard to pre-harvest contractors and only a small number of the growers were involved in direct marketing of their produce in the markets. In recent times, due to the availability of market information, citrus growers are becoming more market oriented and shifting away from the customary practice of selling the orchard production before harvesting and are directly marketing their produce in national as well as in international markets.

There are few challenges and opportunities that can be addressed prudently to make Pakistan citrus industry more flourishing and prosperous. The biggest opportunity lies in the export horizon, which if tapped can be a good source of export revenue.

www.intechopen.com

www.intechopen.com

A Survey of Pakistan Citrus Industry

By Muhammad Imran Siddique and Elena Garnevska

Abstract

Pakistan is producing more than 30 types of different fruits of which citrus fruit is leading among all fruit and constitutes about 30% of total fruit production in the country. Above 90% of citrus fruits are produced in Punjab province and distributed through different value chains in domestic as well as in international markets.

A large part of citrus fruit produced in Pakistan is mostly consumed locally without much value addition; however, 10–12% of total production is exported after value addition. The value chains are very diverse, and a number of different players actively participate in these chains, which ultimately decide the destination of citrus fruit in these supply chain(s). Knowing all these facts, the main aim of this research is to identify different value chains of citrus fruit (Kinnow) in Pakistan and also to identify and discuss the role and function of different value chain players in the citrus industry in Pakistan.

A survey involving of different players of Pakistan’s citrus industry was conducted in 2013–2014 to better understand the citrus value chain(s). Using a convenience sampling technique, a total of 245 respondents were interviewed during a period of 4–5 months from three leading citrus-producing districts.

It was found that citrus value chains can be classified into two major types: unprocessed citrus value chain and processed citrus value chains. It was also found that in the past, a large number of citrus growers were involved in preharvest contracting for their orchards and only a small number of citrus growers sold their orchards directly into local and foreign markets. The proportion has been gradually changed now and growers are becoming progressive and more market oriented.

1. Pakistan citrus industry

The agriculture sector plays a pivotal role in Pakistan’s economy and it holds the key to prosperity. A number of agricultural resources, fertile land, well-irrigated plains and variety of seasons are favourable for the Pakistan agricultural industry. Despite the decline in the share of agriculture in gross domestic production (GDP), nearly two-thirds of the population still depend on this sector for their livelihood [1]. Agriculture is considered as one of the major drivers of economic growth in the country. It has been estimated that in 2014–2015, the total production of agriculture crops was 116 million tonnes. Pakistan produces about 13.5 million tonnes of fruit and vegetables annually. In 2014–2015, the total fruit production was recorded at 7.01 million tonnes, which composed of 48.3% of the total fruit and vegetables production in the country [2, 3].

1.1. Citrus production

The overall trend for all fruit production in Pakistan is increasing except for the year 2006–2007, when a great decrease of production of all fruits as well as citrus fruits was observed due to unfavourable weather (hailstorm) and water shortage, as shown in Figure 1. The area under all fruits and production both has been increasing gradually. Citrus fruit is prominent in terms of its production followed by mango, dates and guava. The total citrus production was 2.4 million tonnes in 2014–2015 that constitutes 35.2% of total fruit production) [3]. Citrus fruit includes mandarins (Kinnow), oranges, grapefruit, lemons and limes, of which mandarin (Kinnow) is of significant importance to Pakistan.

Figure 1.

Area and production of all fruit in Pakistan. Source: [3, 5, 6].

Pakistan’s total production of citrus fruit (primarily Kinnow) is approximately 2.0 million metric tonnes annually. Although there is no remarkable increase in area under citrus production, the production has increased up to 30.8% since 1991–1992. In 1991–1992, Pakistan produced 1.62 million tonnes citrus, which increased to 2.1 million tonnes in 2008–2009 and 2.4 million tonnes in 2014–2015 [3].

The production of citrus fruit has been increasing since 1993–1994; however, it started to decline in 1999. The citrus fruit crop requires a critical low temperature for its ripening which if not achieved may lead to decline in the production of fruit [4]. Therefore, one of the reasons of varied citrus fruit production might be due to the temperature variations in the citrus growing areas of Pakistan.

Such a great variation in temperature was recorded in 2006–2007 in citrus-producing areas due to which citrus production dropped from 2.4 to 1.4 million tonnes; however, the area under citrus fruit orchards remained the same [3].

In Pakistan, citrus fruit has been predominantly cultivated in four provinces, namely: Punjab, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK), Sindh and Baluchistan. Among all four provinces, Punjab is considered to be the hub of citrus production. Table 1 represents the major citrus growing districts in all the four provinces of the country.

Province | Major districts |

|---|---|

Punjab | Sargodha, Toba Tek Singh, Mandi Bahauddin, Sahiwal, Khanewal, Vehari, Bahawalpur, Multan, Okara, Layyah, Jhang, Kasur, Bahawalnagar, Faisalabad |

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) | Malakand, Swat, Nowshera, Lower Dir, Dera Ismail Khan, Mardan, Haripur |

Sindh | Naushero Feroze, Khairpur, Nawabshah, Sukkur, Sanghar |

Baluchistan | Nasirabad, Dolan, Lasbela, Gwadar, Sibi, |

Table 1.

Major citrus growing areas in Pakistan.

Punjab province, according to Pakistan Horticulture Development and Export Company (PHDEC) (2005), produces more than 90% of total Kinnow production whereas KPK mainly produces oranges among all citrus fruits in the country. Sargodha, Toba Tek Singh and Mandi Bahauddin are three known districts for their citrus production in Punjab province. Different varieties of citrus fruits are also grown in small proportions in other districts.

Mandarins (Feutrell’s Early and Kinnow) and sweet orange (Mausami or Musambi and Red Blood) are very important among all the citrus varieties cultivated in Pakistan. Table 2 shows different varieties of citrus produced in the country. Punjab province, being the hub of citrus production (Kinnow), produced 97.1% of citrus fruit (Kinnow) in 2014–2015 [3].

Sweet Orange | Succri, Musambi, Washington Navel, Jaffa, Red Blood, Ruby Red and Valencia Late. |

Mandarins | Feutrell’s Early and Kinnow |

Grapefruit | Mash Seedless, Duncan, Foster and Shamber |

Lemon | Eureka, Lisbon Lemon and rough Lemon |

Lime | Kagzi lime and Sweet lime |

Table 2.

Varieties of citrus fruit in Pakistan.

In Punjab province, three districts, Sargodha, Toba Tek Singh and Mandi Bahauddin, constitute around 55% of the total area under citrus cultivation and produce nearly 62% of citrus fruit [6]. In Sargodha district, Bhalwal produces 650,000 metric tonnes of Kinnow annually and is considered as the centre of Kinnow (mandarin) production (Pakistan Horticulture Development & Export Company (PHDEC), 2005). Figure 2 demonstrates citrus fruit production in four provinces of Pakistan.

Figure 2.

Province-wise production of citrus fruit in Pakistan.

In 2014–2015, the total citrus production in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) was 1.29%, in Sindh 1.26% and in Baluchistan it was 0.29%. In the late 1990s, the production of citrus fruit in the Baluchistan province increased and it was due to the increase in the area under citrus cultivation and hence production under citrus fruit was increased in Baluchistan in the late 1990s [3, 6, 9].

In Punjab province, Kinnow production was 1.80 million tonnes followed by oranges, which was about 94 thousand tonnes in 2009–2010 among different varieties of citrus fruits. In Punjab, Kinnow was 87.1% of the total citrus production and 80.3% of the total area under citrus cultivation. Oranges come next to Kinnow in production and area under cultivation and constitutes 4.5% of the total citrus production and 6% of the total area under citrus cultivation in Punjab. Grapefruit production is the lowest and it was only 3 thousand tonnes. Different types of citrus grown in Punjab province in 2009–2010 are shown in Table 3.

Production and area of different types of citrus fruit in Punjab | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Type of Citrus | 2011–2012 | Percent of total citrus production | |

Area (‘000’ Hectares) | Production (‘000’ tonnes) | ||

Kinnow | 154.6 | 1876.0 | 89.43 |

Oranges | 9.4 | 80.0 | 3.81 |

Musambi | 7.2 | 61.5 | 2.93 |

Mandarin | 1.2 | 9.3 | 0.44 |

Sweet Lime | 3.9 | 29.5 | 1.41 |

Sour Orange | 0.1 | 1.0 | 0.05 |

Lemon | 4.6 | 26.0 | 1.2 |

Sour Lime | 0.8 | 3.8 | 0.2 |

Grapefruit | 0.3 | 2.3 | 0.1 |

Other | 1.2 | 8.4 | 0.4 |

Total | 183.2 | 2097.7 | 100.00 |

Table 3.

Production of different types of citrus fruit in Punjab.

1.2. Citrus consumption

The consumption of fresh citrus fruit in developing countries has been increasing; however, it is still low compared to the developed countries. In Pakistan, per capita consumption of citrus fruit is almost static since 1999 except in 2007 when it dropped to 7.8 from 13.5 kg, as shown in Figure 3. The rapid increase in the population may be one of the major factors keeping the consumption level nearly constant despite the increase in citrus production from 1.8 million tonnes in 1999 to 2.1 million tonnes in 2009. Per capita income has increased from US$450 in 1999 to US$917 in 2009 [11].

However, the sharp decline in per capita consumption in 2007 was a result of lowest production of 1.4 million tonnes from 2.4 million tonnes in 2006, which resulted in lower domestic supply and availability of citrus fruit in the country. The high peak of 2005 in Figure 3 reflects the highest per capita consumption of citrus fruit due to decreased exports of the citrus fruit from 151.3 thousand tonnes in 2004 to 79.2 thousand tonnes in 2005.

Figure 3.

World citrus fruit consumption trend.

Figure 3 shows the annual per capita consumption (kg) of fresh citrus fruit in important countries. There was an increase in per capita consumption in Brazil that reached to the highest level in 2011 and then dropped very sharply in 2012 and 2013.

1.3. Citrus exports

With the changing consumer preferences towards consumption of fresh and convenience food, the global demand for fresh fruit is increasing [8, 13]. Pakistan is one of the largest citrus producing countries and ranked 13th in the production of citrus fruit [5]. It has been observed that fresh citrus exports from Pakistan have been increasing since 1995–1996 as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Pakistan citrus area, production and exports.

Among all citrus fruits, Kinnow mandarin constitutes about 97% in the total exports of citrus fruit from the country [8, 14]. In 2014–2015, the total exports of citrus fruit from Pakistan were 393 thousand tonnes, which account for a total value of $204 million that represents about 16.4% of the total citrus production. As compared to 2000–2001, the total exports of citrus were exactly threefold in 2009–2010 which accounted for $99.4 million of foreign revenue. Despite the increase in production, only a small amount of citrus fruit (8–12%) is being exported.

The majority of the farmers in Pakistan own and cultivate a small size of agricultural land of less than 2 hectare. However, in Punjab, average citrus farm size was 12.3 hectare, which is considered relatively large compared to other crops [15]. The size of citrus orchard ranges from less than 1 hectare to as big as 65 hectare in different regions of the country. A few large citrus growers do exist; however, small and medium size growers are the majority [16].

The agricultural value chains in Pakistan are very diverse and start with citrus growers/producers. Like other fruits, citrus fruit value chain is primarily controlled by the private sector.

However, Government plays a facilitative role by providing basic infrastructure and regulatory measures for easy business transactions. It is generally observed that marketing intermediaries exploit agricultural crop producers by charging high margin on their investment [16]. Citrus fruit value chain(s) starts with the involvement of pre-harvest contractor directly with citrus growers. According to Chaudry [15], the typical citrus value chains in Pakistan are shown in Figure 5. The role of each player in the citrus value chain is presented later in the results and discussion sections.

Figure 5.

Value chains of citrus in Pakistan.

All the players involved in these value chains execute their usual functions as they do in other food value chains; however, the pre-harvest contractors are the most important powerful player in Pakistan citrus value chains [15, 16].

Keeping in mind the increase in production, constant domestic consumption and available surplus of citrus fruit for export, a number of questions arises; how many different citrus value chains operate in the country? Who are the players involved in the citrus value chains? Despite the availability of citrus fruit, why only a small amount of citrus fruit is being exported? To answer these questions, this study aims to identify and analyse different value chains of citrus fruit (Kinnow) that are operating in Pakistan and also to identify and discuss the role and functions of each value chain players in the citrus industry in Pakistan. Furthermore, this study identifies future opportunities and challenges of citrus sector in Pakistan.

2. Method

Both qualitative (exploratory) and quantitative (descriptive and inferential) research methods were used for this study depending upon the research questions. A survey involving different players of Pakistan’s citrus industry was conducted in 2013–2014 using semi-structured interviews assisted by a questionnaire. Primary data were collected through surveys, while secondary data were obtained from published documents, reports, journals and government publications of various public and private institutions and departments.

Using a convenience sampling technique, a total of 245 respondents were interviewed during a period of 4–5 months from three leading citrus producing districts, namely Sargodha, Toba Tek Singh and Mandi Bahauddin. The respondents included were 126 citrus growers, 99 pre-harvest contractors and 20 processing factories/exporters from these three districts. Due to unavailability of population size (sampling frame), time and budget constraint, a convenient sampling technique was used for the selection of the respondents.

The underlying reason of interviewing different players in the citrus value chains was to study closely their functions and participation in different existing value chains. It also helped identifying and understanding different value chains operating in the country. This study also identified future opportunities and challenges of citrus sector in Pakistan.

A statistical package Predictive Analytics Software–version 21 (PASW-21), previously known as Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS), was used to analyse the collected data. Fisher’s exact test was used to test the significance of different demographic variables and the selection of the value chain particularly involving pre-harvest contractor.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Citrus (Kinnow) value chain systems

The results of this study revealed that citrus (Kinnow) value chains can be classified into two major types: unprocessed citrus (Kinnow) value chain and processed citrus (Kinnow) value chain. The description of these value chains is presented in the next section.

3.1.1. Unprocessed citrus (Kinnow) value chain

Unprocessed citrus (Kinnow) graded and packed before selling to the local market and does not include usually washing and waxing. Figure 6 presents the unprocessed citrus (Kinnow) value chain in the country.

Figure 6.

Unprocessed citrus (Kinnow) value chain for local market.

About 50–60% Kinnow is marketed in the country for domestic consumption while nearly 30% Kinnow is accounted for post-harvest losses [8]. Citrus growers, pre-harvest contractors, local (provincial) commission agents, inter-provincial commission agents, local wholesalers, inter-provincial wholesalers, local and inter-provincial retailers are different actors of unprocessed citrus (Kinnow) value chain in Pakistan.

The major players of the unprocessed citrus (Kinnow) value chain are citrus growers and pre-harvest contractors and their marketing strategies intensely affect the citrus supply chain in the country. It was common practice in the past where about 90% of the citrus growers used to sell their orchard to pre-harvest contractors.

The predominate reasons include unavailability of finances, lack of market information, ease of the transaction, avoiding the future price fluctuations and norms of the business [15]. Citrus growers are becoming more market oriented and adapting different marketing channels to get high price for their products instead of selling solely to pre-harvest contractors. The improved education level, government support and technological developments are the reasons for this change. One of the citrus growers replied when asked about direct marketing of his fruit in the market:

‘Now nearly every citrus grower has an access to prices of different local and provincial markets which has helped us to involve ourselves into direct marketing of our fruit. Being ignorant of different market prices in the past, we were unable to decide where to sell, hence carried out with the pre-harvest contractor. Thanks for the government support, who provided us this opportunity to market our produce directly and earn good profit’.

3.1.2. Processed citrus (Kinnow) value chain

Kinnow processing is of two types: (1) for export and involves washing, waxing, grading and packing and (2) for juice extraction.

3.1.2.1. Processed citrus (Kinnow) value chain for export

Only 8–12% Kinnow is processed for export to different countries. In 2013–2014, the major exports of Kinnow mandarin were to Afghanistan (113,000 tonnes), Russian Federation (72,000 tonnes) and United Arab Emirates (68,000 tonnes). A complete list of countries is attached in Appendix A [17].

Processed citrus (Kinnow) value chain comprises citrus growers, pre-harvest contractors, local commission agents/wholesalers, Kinnow processing factories and exporters (Figure 7). The processed citrus value chain and unprocessed citrus value chain are nearly similar except Kinnow processing factory, and exporters are involved in processed value chain at the end stage of the process.

Figure 7.

Processed citrus (Kinnow) value chain for export.

Citrus growers, pre-harvest contractors and commission agents sell citrus fruit directly to factories (Kinnow processing) and exporters. Pre-harvest contractors and some commission agents act on behalf of these Kinnow processors and exporters and purchase citrus fruit for them. These agents are provided with some credit or advance payments to buy citrus fruit. A good family and financial background, market reputation and ability of constant supply of fruit in the season are the qualities of sellers preferred by these Kinnow processors and exporters. Sellers to processors and exporters are paid through cheques. One of the exporters commented on the selection of seller (grower/contractor/commission agent/wholesaler):

‘In our export business, we need to make promises with our importers for certain quantity of fruit in the season; therefore, all exporters try to deal with the seller who can commit constant supply of citrus. A well reputed, financially strong with good moral character seller is our first choice to deal with’.

In Sargodha, about 150 Kinnow processing factories are functioning but only 25–30 processing factories are exporting citrus to different countries. The reasons of such a low export from the country include high demand for seedless Kinnow (hybrid mandarin) in the developed countries (not produced in Pakistan), marketing practices and failure to meet the quality certification standards. One of the respondents who wanted to export to European countries commented:

‘I always take good care of my orchards; hence, I manage to get good quality fruit in each season. Realising the quality, I decided to export my fruit to Europe last year but I was told that I should grow citrus to meet quality certification standards required for export which I am following now. Hopefully, I would be able to export my citrus to Europe soon’.

A few processing units are also being constructed in other districts as well, for example, district Mandi Bahauddin, district Toba Tek Singh and district Multan.

3.1.2.2. Processed citrus (Kinnow) value chain for juice extraction

A total of 52 fruit processing and juice extraction factories are operating in Pakistan [18]. Only five of them are processing citrus fruit for juice extraction. About 6% to the total citrus produced in the country is processed for juice extraction [18]. These factories are concentrated in the major citrus producing areas such as Sargodha, Bhalwal and Mateela cities. Citrus growers and pre-harvest contractors sell mostly drop off, low quality and non-marketable fruit to these juice factories, which process it into juice concentrate and sell it to different retail shops and supermarkets in the country.

One of the contractors who supply to exporters and processors replied:

‘I always try to sell exporters and processors because they pay premium price for my fruit. However, these exporters and processors only purchase selective fruit from me and leave small size, non-uniform and unripe fruit. I don’t mind it; I sell this non-selective fruit to juice factories and recover my cost. Job done’.

Figure 8 shows different functionaries of processed citrus (Kinnow) value chain.

Figure 8.

Processed citrus (Kinnow) value chain for juice extraction.

3.2. Description of different value chain players

Different players of citrus (Kinnow) value chain including citrus growers, pre-harvest contractors, commission agents, wholesalers and retailers are described and discussed below.

3.2.1. Citrus growers

The results of this study revealed that majority of the citrus growers (76.2%) were 31–60 years of age and only 6.3% were quite young (under 25 years old) in the citrus industry. However, about 17% citrus growers were above 60 years of age. The literacy rate was more than 90% in the citrus growers (having at least 5 years of schooling) and only 3.2% respondents were illiterate. It was reported that the literacy rate was increasing in the citrus growing areas in Pakistan, thus providing basis for the growth of citrus growers and making them more market oriented [19]. The results also showed that nearly 80% of the citrus growers were very experienced and were involved in the citrus industry for many years.

The size of the citrus orchards was small, and majority of the citrus growers possessed less than 20 acres (Table 4).

Age (years) | 1.0–30 | 31–60 | 61–90 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Percent (%) | 6.3 | 76.2 | 17.5 | |

Education | Illiterate | Undergraduate | Graduate | Postgraduate |

Percent (%) | 3.2 | 74.6 | 15.1 | 7.1 |

Experience (years) | ≤10 | 11–25 | >26 | |

Percent (%) | 21.4 | 40.5 | 38.1 | |

Area under citrus (acres) | 1.0–20 | 20.1–60 | 60.1–160 | |

Percent (%) | 53.2 | 30.2 | 16.7 | |

Sell orchard to | Pre-harvest contractor | Commission agent/wholesaler | Processing factory/exporter | Different buyers |

Percent (%) | 46% | 30% | 18% | 6% |

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics for citrus growers.

The size of these citrus orchards was further reduced when the orchard was divided among the next generations. Previously, it was found that majority of the citrus growers (more than 90%) preferred to market their produce through pre-harvest contractors, thus reducing the direct involvement of the citrus growers in the value chains. Due to better government policies in the education sector and increasing market awareness, the level of literacy rate has increased in the last 10 years.

All citrus growers were educated and became aware of market information and opportunities. As citrus growers are becoming more market oriented, they are searching for reliable market information to find alternative value chains other than selling directly to pre-harvest contractors. According to this study, about 46% of the citrus growers are selling their orchard to pre-harvest contractors. This finding is contrary to the previous study conducted by Chaudry [15] and Ali [16] who reported that 95% of citrus growers sold their orchards to pre-harvest contractors about 15 years ago.

Nearly 30% of the citrus growers in the sample sold their orchard to commission agents/wholesalers or exporters. Price was settled on commission basis at a rate of 7–8% of the total sale price of the produce with the commission agent or wholesaler. Exporters and processing factories usually announce citrus fruit purchase price per 40 kg for the season. It is negotiable in certain cases, for example, if citrus grower(s) contract for complete season fruit supply.

There is no government control over prices of Kinnow and it is determined by market forces (demand and supply). The only problem while selling to exporter was that it only purchased good quality fruit with good size and colour (selective fruit purchase). This was one of the reasons, citrus growers switch to alternative buyers who purchase and pay the price for the whole produce. Nearly 6% citrus growers sold their produce to different buyers instead of selling to only one buyer.

3.2.2. Citrus pre-harvest contractors

A total of 99 pre-harvest contractors were interviewed for the study. About 70% pre-harvest contractors had US$0.1–$0.5 million business volume and were considered medium-sized contractors. Pre-harvest contractors either used their own money to buy the orchards or acted as an agent on the behalf of the other actors of the citrus supply chain, for example, commission agents, wholesalers, processors or exporters. The results revealed that majority of the pre-harvest contractors (80% of the respondents) had more than 10 years of experience, as shown in Table 5. However, small pre-harvest contractors had less than 10 years of experience due to the fact that they work seasonally in the market and were not a regular player of citrus supply chain in the country.

Majority of the citrus growers were well educated and experienced businessmen, whereas, only 35% pre-harvest contractors were illiterate (not even 2 years at school) but they work with either well-educated business partners or family members (brother, son).

Size of contractors | Less than $0.1 million | $0.1–$0.5 million | More than $0.5 million |

|---|---|---|---|

Percent (%) | 20% | 70% | 10% |

Experience | Less than 10 years | 10–20 years | More than 20 years |

Percent (%) | 20% | 45% | 35% |

Sell fruit to | Commission agent/wholesaler | Exporter | Different buyers |

Percent (%) | 50% | 40% | 10% |

Education status | Illiterate | Educated to minimum level | |

Percent (%) | 35% | 65% |

Table 5.

Citrus pre-harvest contractors general information.

About 50% of the pre-harvest contractors sold their fruit to commission agents or wholesalers, as shown in Table 5. Price is paid on commission basis at a rate of 7–8% of the total sale price of the produce. Usually, there was 1-year contract (written or verbal) between pre-harvest contractors and commission agents or wholesalers to supply a certain quantity of fruit under the contract on a fix price. Nearly 40% of the pre-harvest contractors sold their fruit directly to exporters. Usually, price was announced by processors and exporter association; however, in some cases it was negotiable.

Citrus growers sold their orchards in advance to contractors for different reasons. Firstly, citrus growers in Pakistan were not financially sound enough to market their produce. Secondly, responsibility of looking after the orchard is shared between farmers and pre-harvest contractors, and lessen farmer’s financial burden for fertiliser and pesticides which is now provided by the pre-harvest contractors. On the other hand, pre-harvest contractor took control over the produce and bargaining power for selling the fruit in the market. One of the citrus growers commented on pre-harvest sale of his orchard:

‘It is always a problem for me to buy inputs once my orchard starts flowering. Pre-harvest contractor, on one hand, purchase my orchard well in time and on the other hand, help in providing me the required inputs which otherwise I cannot afford’.

3.2.2.1. Types of contractors

There are different types of citrus orchard contractors operating in the country. They can be divided into three broad categories on the basis of their purchasing power of citrus fruit for trading purposes.

- Small-sized contractors

Small-sized contractors with buying power less than US$0.1 million (1 US dollar = 85 PKR) are called ‘Den Daar’ and usually work domestically in the local markets only. Being a small-scale operator and limited finances, they work in groups and buy an orchard on shared basis. They sell fruit on daily basis in the local market where they are called ‘Phariwala’ in the local language or sometimes they sell directly to a wholesaler or commission agent. - Medium-sized contractors

Medium-sized contractors buy fruit that value between US$0.1 to US$0.5 million. They work for commission agents/wholesalers/exporters and usually do not invest their own money. Sometimes they buy the orchard with their own money but usually they contract with the citrus grower at the pre-harvest stage by estimating the future production from the orchard and also make a future contract with the commission agents/wholesalers/exporters. This way they play an intermediary role between two parties without investing their own finances. Commission agents/wholesalers/exporters are then responsible to pay all the money to the contractor in the form of partial payments. Initially, commission agents/wholesalers/exporters pay one-fourth of the total orchard value under the contract to the contractor who pays to the citrus grower as an advance. Usually, this whole agreement is not documented; therefore, there are chances of fraudulent through this whole transaction. One of the possibilities is that citrus grower might refuse to sell at the harvest stage due to high price offered by other contractors or buyers. - Large-sized contractors

The large-sized contractors are few in number and usually buy orchards from medium- and large-sized citrus growers. They typically have strong finances with purchasing power greater than US$0.5M. Sometimes, they work for commission agents/wholesalers/exporters and buy orchards/fruit for them. They usually sell fruit to exporters and in different local or inter-provincial markets depending upon the price. However, if the prices are low, they can store fruit in the cold storages (privately owned) for some time and sell in the market when price increases.

3.2.3. Descriptions of the other players involved in Pakistan citrus value chains

- Commission agents

The commission agent (‘Arhti’ in local language) purchases citrus fruit from producers and/or pre-harvest contractors and sells it to wholesalers /retailers/exporters. Occasionally, the commission agents work as a wholesaler and sell directly to retailers or exporters. In some cases, citrus growers and contractors may use commission agents as a selling agent to sell in the local and far distant markets. Commission agents usually do not take the title or possession of the commodity (citrus fruit) and act as a link between buyer and seller and facilitate the whole transaction and receive a fixed amount as a commission for their services.

Nearly all the commission agents provide credit to citrus growers and contractors with the condition that they would sell their fruit to them. Usually, contractors do not receive any payments until the end of contracting period. At the end of contracting season, contractor is paid based on the agreement between the parties. - Wholesalers

Wholesalers buy fruit in large quantities from commission agents and pre-harvest contractors or directly from the citrus growers. Contrary to commission agents, wholesalers take the possession of the commodity and perform different value-added functions like grading, sorting, washing, cleaning before selling to the local market, inter-provincial wholesalers, retailers and consumers. Usually, wholesalers extend credit to pre-harvest contractors who purchase fruit for them from the citrus growers. In that case, the pre-harvest contractors work as a commission agent for that particular wholesaler. - Retailers

In Pakistan, citrus fruit is a table fruit and consumed fresh. It is primarily sold by fruit shops, stallholders and street hawkers (using animal driven carts). The fruit shops are situated mostly in consumer markets, near residential areas, along roadsides. It is very convenient to buy fruit from these shops at reasonable prices; however, a large quantity of citrus fruit is also sold by street hawkers on bicycles or animal-driven carts all around in the cities and country side. Though they sell only a small amount of fruit, yet they are necessary part of the whole citrus value chain in delivering the product to end consumers. These retailers also known as ‘Phariwala’ buy fruit directly from small-sized pre-harvest contractors.

4. Opportunities and challenges for Pakistan citrus industry

Citrus growers are becoming more market oriented; therefore, by increasing the market-led opportunities like crop management, improving quality of the fruit, adding more value through processing will develop and expand Pakistan citrus industry. With newly developed infrastructure and transportation systems, domestic as well as international supply chain of citrus industry will be better established towards becoming more efficient and reducing the overall waste.

The exports of citrus fruit from the country are only 8–12% of the total production; therefore, there lies a great opportunity and potential in the export of citrus fruit. By developing the quality management practices, improving supply chains, establishing certification scheme and reducing post-harvest losses, the exports can be increased particularly in the European countries, Middle East, South East Asia, China and Central Asia markets.

The challenges that Pakistan citrus industry is facing include, but not limited to, agro-ecological climate with extreme summer temperatures, frost in winter and water scarcity/shortage.

Inefficient production, irrigation methods, post-harvest losses, low grade fruit, poor disease control, lack of fertilizers/manures in the soil and inefficient supply chains are the other major challenges in citrus value chains. To overcome these challenges, citrus grower association (private entity owned by growers) is working closely with government departments and institutions to provide required inputs and expertise to growers that can raise the quantity and quality of fruit.

The lack of skilled and trained labour for fruit picking poses another marketing constraint, which in turn affects the quality of picked fruit. Even the lack of seasonal or temporary labour for fruit picking is also a challenge. The efforts are being made by extension workers, medium and large citrus growers to provide necessary training and accommodation facilities to the labour. This will not only decrease the fruit damage during picking but also ensure the availability of the labour when required.

Good agricultural practices (GAPs) and sanitary phytosanitary (SPS) measures are required for markets such as Europe, the USA and Oceania. However, efforts are being made, both publicly and privately, to uplift the quality of citrus fruit in order to get required certification for export.

5. Conclusion

The agro-food value chain system in Pakistan is very diverse and nearly all citrus value chains are dominated by citrus growers, pre-harvest contractors and exporters of citrus fruit with the involvement of other value chain members like commission agents, wholesalers, and retailers.

It was found that citrus value chains can be classified into two major types : unprocessed citrus value chain for local markets and processed citrus value chains for export and juice extraction. In Pakistan, the majority of citrus orchards are less than a hectare; however, the average size of citrus orchard is almost 20 hectare. In the past, mostly citrus growers sold their fruit or orchard to pre-harvest contractors and only a small number of the growers were involved in direct marketing of their produce in the markets. In recent times, due to the availability of market information, citrus growers are becoming more market oriented and shifting away from the customary practice of selling the orchard production before harvesting and are directly marketing their produce in national as well as in international markets.

There are few challenges and opportunities that can be addressed prudently to make Pakistan citrus industry more flourishing and prosperous. The biggest opportunity lies in the export horizon, which if tapped can be a good source of export revenue.

Chapter: Citrus Value Chain(s): A Survey of Pakistan Citrus Industry

Pakistan is producing more than 30 types of different fruits of which citrus fruit is leading among all fruit and constitutes about 30% of total fruit production in the country. Above 90% of citrus fr