flamer84

BANNED

- Joined

- Mar 6, 2013

- Messages

- 9,435

- Reaction score

- -14

- Country

- Location

Ceausescu and Romanian Sovereignty

Romania was an important German ally in WWII, but changed sides on 23 August 1944. In accordance with agreements of the Jalta Conference, the country subsequently came within the Soviet sphere of influence, and was one of signatories of the Warsaw Pact.

The Romanian leadership managed to convince the Soviets to withdraw all troops from the country in June 1958. After that, Romania slowly adopted a form of nationalistic communism quite similar to that of neighboring Yugoslavia and became the least compliant of the Soviet satellites. In 1964 cooperation between the Romanian and USSR intelligence services virtually ended and relations with Moscowworsened especially since the dictator Nicolae Ceausescu established himself in power in 1965. Subsequently, in some matters, Romaniahas taken stands in direct opposition to Soviet policy, as in its continuing diplomatic relations with Communist China, Albania, and Israel.

Before long, the Romanian dictator was a thorn in the side of the Soviets. In August 1968, when the USSR and all other countries of the Warsaw Pact intervened in Czechoslovakia, Ceausescu denounced the invasion in a public speech, declaring it for a brutal interference in the internal affairs of a sovereign country. Romania was the only Warsaw Pact country not to participate, and subsequently it remained only a passive member of the Eastern Bloc: since August 1968, the Romanian ground forces did not participate in any Warsaw Pact exercise. Ceausescu showed strong tendencies on Romanian self-sufficiency, especially in regards of procuring armament for the military. Thus, while Romania was receiving substantial military equipment and training from the USSR in the 1950s, since the late 1960s it began searching for alternatives - in country, in the West and among non-aligned states. During the following years Ceausescu established an increasingly good image of himself and his country in the West, which was mostly due to his stand against the Soviets. Good relations with France (resulting in contracts for license production of Alouette III and Puma helicopters, as well as Renault cars), United Kingdom (resulting in contracts for license production of Rolls Royce Viper engines, BAC 1-11 and BN-2 Islander aircraft), Canada (resulting with the first non-Soviet nuclear reactor built in Eastern Europe), USA (with particularly good relations with Nixon’s administrations, Boeing 707 deliveries) were rising eyebrows in Kremlin time and again.

However, Ceausescu ruled Romania with help of the "Departamentul Securitatii Statului" (DSS) – the State Security Department, popularly known as “Securitatea” which was foremost busy controlling all aspects of public life in Romania through intelligence and repression. Securitatea was involved in espionage of literally everybody: like the former “Stazi” in East Germany, it maintained a wide net of informants, infiltrating economic structures, financial institutions, the executive and the legislature. Intercepting phone calls and placing "bugs" were also common practice. In this way, the DSS was perceived as being omni-present in every bureau, shop or home around the country and maintained order as much trough direct actions as trough the fear generated in the public by the fact that it could "listen" anything, anytime, and anybody could potentially be an informant.

In the 1980s, the Romanian regime became increasingly radical and isolated, with a very strong nationalist character. Ceausescu's clique developed an immense personality cult for him and his wife, surpassed in size and lack of realism only by the North Korean one. Like Ceausescu, Securitatea was hated in the public, but nobody was able to admit this openly, then the omni-presence of informants and agents ascertained that any dissident could be swiftly and decisively dealt with. At the political level, the communist regime saw the “Perestroika” efforts of the Soviet leader Gorbachev, almost as another Soviet intervention in Czechoslovakia; his drive to replace old Communist leaders of East European countries by reformers was considered dangerous.

By 1989, Romania was the last of the Warsaw Pact countries in which there were no reforms, quite on the contrary food and energy shortages began to resemble those found during a war or inside a third world country. The reformist Soviet leadership was not interested in having a potentially hostile regime on its borders; however it could not support an opposition or a reformative wing within the Romanian Communist Party (PCR) as there were none. Besides, the Securitatea would quite certainly learn about such efforts. But, if there was a popular uprising - even one sparked by foreign agents - the snowball effect was guaranteed due to the immense public discontent and in the case of a military repression, the Soviets would be provided with a reason to launch an invasion with the reasoning of “protecting Romanian people from their own dictator”.

Air Force

Romania has an old and proud aviation history, being one of the first countries where aircraft were imagined, built and flown, as well as a rich history of domestic aerospace industry. The first military air unit of the Romanian Army was established already in 1893, and was a balloon observation unit. As early as 1903, the first plans for an original aircraft were published, but it was not before 1906 that this plane was indeed flown by its inventor, Traian Vuia. Nevertheless, already four years later the first fan-jet powered plane in the world was built and flown – even if in an uncontrollable fashion – by Henri Coanda.

Romania became only the fifth nation world-wide to have an air force established as a separate military branch: the Romanian Flying Corps came into being already on 30 April 1913, as a branch subordinated directly to the Ministry of War, and having 80 pilots and 25 air observers at the time. It participated in the Second Balkan War shortly thereafter, in June-July 1913, flying observation and liaison sorties. During World War I, this corps actively participated in fighting against Austro-Hungarian, German and Bulgarian forces, even after most of the country was overrun by these, enjoying a very strong French support. The air arm experienced its “Golden Ages” in the 1920s and 1930s, when it was mainly equipped with domestic airplanes manufactured by no less but seven Romanian factories. Over 2.000 military and civilian airplanes were built by Romanian companies within 18 years.

In 1940, a number of German instructors arrived and the "Aeronautica Regala Romana" - ARR, Royal Romanian Aeronautics, was completely reorganized and then significantly increased, so that it participated very actively in the war against USSR, between 1941 and 1944. By the early 1944, however, the ARR was severely depleted and weakened due to the increasing number of Allied attacks against strategically important oilfields in Ploiesti area. On 20 August 1944, the Red Army breached the Romanian-German front in Moldova, and three days later a coup led by King Michael deposed the military dictator Antonescu and his cabinet, leading to fierce fighting between the Romanians and Germans, on 24 and 25 August, involving both air forces. When the Soviets finally reached Bucharest, on 30 August, the south of the country was already free of all German troops: the rest of these retreated behind Transylvanian mountains. Thus, the Romanians changed sides on their own, right before being overrun by the Soviets. Afterwards, the ARR actively fought against Germany and Hungary during campaigns over Romanian, Hungarian, Czechoslovak and Austrian territories.

In 1947, the prefix “Royal” was dropped and the Air Force, “Fortele Aeriene ale Republicii Populare Romane” – Air Force of the Popular Republic of Romania – was reorganized along Soviet lines. On 10 August 1950, a new national insignia derived from the Red Star design was adopted. The first Yakovlev Yak-23 and Yak-17UTI fighter jets were supplied in 1951, followed by MiG-15s, the next year, and MiG-17s and Il-28s in 1955, when the official designation of the air force was changed to "Aviatia Militara" (AvM) - Military Aviation. In 1958, the first supersonic fighter – MiG-19 – entered service, followed by MiG-21F-13s, four years later. In 1956 the first helicopter unit was established, flying 4 Soviet-made Mil Mi-4s and, starting from 1962, also SM-2 and SM-1s – the Polish made variants of the Mi-1.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Romania re-established its aviation industry and obtained licence for production of some Western types, including Aérospatiale SA.316B Alouette III, SA.330 H/L Puma, Britten-Norman BN-2 Islander and BAC 1-11. Simultaneously, a strike fighter was developed and manufactured in cooperation with Yugoslavia, in the frame of the YUROM project, that resulted in the IAR-93/J-22 Orao – the only non-Soviet fighter-bomber ever built and flown in an air force of a (at least officially) Warsaw Pact member state. Experience accumulated in these programs permitted the development and building of an indigenous jet trainer, the IAR-99.

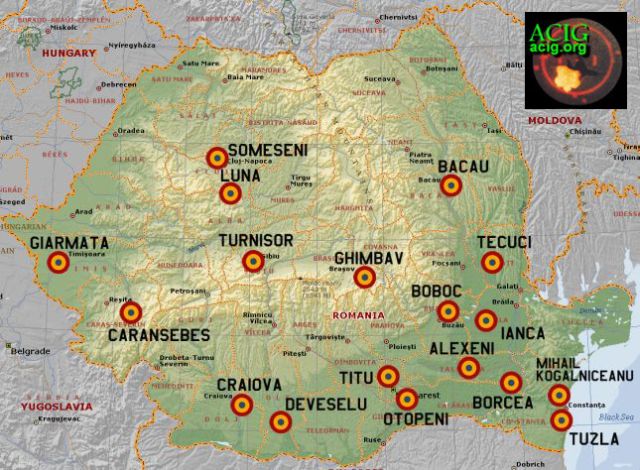

As of 1989, the AvM had approximately 32.000 personnel, of which less than one third were conscripts. The air force had an inventory of 512 combat aircraft, and was also responsible for transport, reconnaissance and helicopters, with the primary mission of defending the country against invasion while protecting and supporting the ground forces and navy. Theoretically divided into three tactical divisions, the AM's basic organizational structure was the Regiment, housed by a single base. The commander in chief in December 1989 was Gen. Iosif Rus.

As far as jets are concerned, they mainly flew Soviet-made MiG-21s and MiG-23s, but many MiG-15s and a few MiG-17 were still available for ground attack, as well as a large number of IAR-93s. Finally, on 21 December 1989, the first 4 MiG-29s arrived in Romania ferried by Soviet pilots (MiG-29 A serials 41, 46 and MiG-29 UB serials 15 and 23), but the first flights with Romanian pilots began only in April 1990. The helicopter fleet consisted of roughly 100 each IAR-316B Alouette III and IAR-330L Puma, plus less than 30 Mi-8T/PS. The lack of a dedicated attack/anti-tank helicopter was partially suplemented by the posibility to arm all helicopter types mentioned above - mostly with unguided rockets. Altough all jet fighter units were trained, besides interception and air combat, for ground attack, only two regiments were designated fighter-bomber regiments and trained specifically for ground attack and CAS.

The “Aurel Vlaicu Flight Academy” had a large number of training aircraft based on three airfields in close proximity to each other, as follows:

Focsani AB (grass airfield)

19 School Liaison Regiment

- IAR-823 and Yak-52

Boboc AB

20 School Fighter-Bomber Regiment

- IAR-823, L-29, L-39ZA and IAR-99

Buzau AB (grass airfield)

21 School Transport Regiment

- An-2R/T and IAR-316B

The operational units were:

Ianca AB

49 Fighter-Bomber Regiment

- 1/49 Fighter-Bomber Squadron, IAR-93MB/DC (not yet operational)

- 2/49 Fighter-Bomber Squadron, MiG-15 (S-102)

- 3/49 Fighter-Bomber Squadron, MiG-15 (S-102)

Mihail Kogalniceanu (near the Black Sea shore)

57 Fighter Regiment

- 1/57 Fighter Squadron, MiG-29A/29UB (not yet operational, replacing MiG-21M/UM)

- 2/57 Fighter Squadron, MiG-23MF/UB

- 3/57 Fighter Squadron, MiG-23MF/UB

- 143 Pilotless Reconnaissance Squadron, VR-3 Reis (Tu-143)

Turnisor AB (Sibiu)

58 Helicopter Regiment

- 1/58 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-330L

- 2/58 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-316B

Ghimbav Airfield/ICA Brasov (Brasov)

58 Helicopter Regiment (det.)

- 1/58 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-316B

Tuzla AB (near the Black Sea shore)

59 Helicopter Regiment

- 1/59 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-330L

- 2/59 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-316B

Tecuci AB

60 Helicopter Regiment

- 141 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-330L

- 183 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-316B

Boteni AB (also known as Titu)

61 Helicopter Regiment

- 1/61 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-330L

- 2/61 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-316B

Craiova AB

67 Fighter-Bomber Regiment

- 1/67 Fighter-Bomber Squadron, IAR-93 A/MB/B/DC

- 2/67 Fighter-Bomber Squadron, IAR-93 A/MB/B/DC

- 3/67 Fighter-Bomber Squadron, MiG-15 (S-102), MiG-17F/PF

Campia Turzii AB (also known as Luna)

71 Fighter Regiment

- 1/71 Fighter Squadron, MiG-21MF/UM

- 2/71 Fighter Squadron, MiG-21M/UM

- 3/71 Fighter Squadron, MiG-21M/UM

Caransebes AB

73 Helicopter Regiment

- 1/73 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-330L

- 2/73 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-316B

Fetesti AB (also known as Borcea)

86 Fighter Regiment

- 1/86 Fighter Squadron, MiG-21MF/UM

- 2/86 Fighter Squadron, MiG-21PFM/U/US

- 3/86 Fighter Squadron, MiG-21PFM/U/US

- 38 Reconaissance Squadron, Harbin H-5R/B, HJ-5

Otopeni AB (Bucharest)

50th Aerial Transport Flotilla An-24V/RV/R/RT, An-26, An-30, BN-2 Islander, ROMBAC 1-11, Il-18, Boeing 707-3K1C; IAR-316B, IAR-330L, Mi-8T/PS, Mi-17, SA365N Dauphin 2

Deveselu AB

91 Fighter Regiment

- 1/91 Fighter Squadron, MiG-21MF-75/UM

- 2/91 Fighter Squadron, MiG-21MF/UM

- 3/91 Fighter Squadron, MiG-21PFM/UM

Alexeni AB

94 Helicopter Regiment

- 1/94 Helicopter Squadron, Mi-8T

- 2/94 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-316B

- 131 Helicopter Navigator Training Squadron, IAR-316B, IAR-330L, Mi-8T

Giarmata AB (Timisoara)

93 Fighter Regiment

- 1/93 Fighter Squadron, MiG-23MF/UB

- 2/93 Fighter Squadron, MiG-21MF-75/UM

- 3/93 Fighter Squadron, MiG-21MF-75/UM

- 31 Reconnaissance Squadron MiG-21R/UM

Bacau AB

CIAv - Centrul de Instructie a Aviatiei (acting as operational conversion unit)

- 1st Squadron, MiG-21M/UM

- 2nd Squadron, MiG-21PFM/US

- 3rd Squadron, MiG-21PF/U (to be replaced by MiG-21M/UM displaced from Mihail Kogalniceanu by MiG-29s)

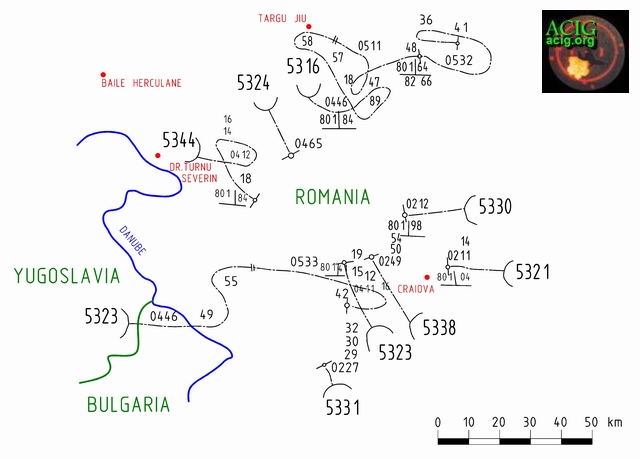

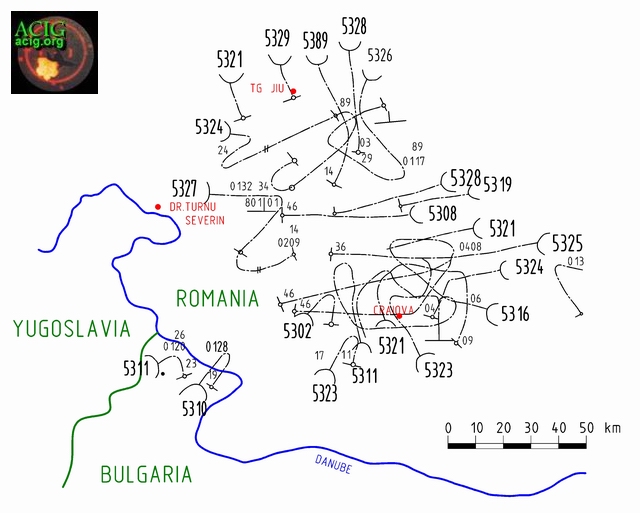

The national air defence system (AAT) was under a different command, being responsible for the radar network and fixed SAM sites, led by Gen. Mircea Mocanu. The main defensive asset was the SA-2 (S-75M3 Volhov) with 5Ia23 type missiles, deployed in 13 sites protecting the Bucharest - Ploiesti - Brasov area. Four SA-3 batteries (S-125 M1A Neva) armed with 5V27D (V-601) missiles were also available, being deployed to form an inner ring to protect the capital. The area around Bucharest and Ploiesti belonged to the 1st SAM Brigade, while Brasov with its vital industries and helicopter factory was defended by the 11th SAM Regiment. Another two SA-2 regiments were available, garrisoned at Galati and Resita (the latter with four batteries deployed in the Deva-Huneadoara-Orastie area). The early warning network consisted of 36 radar sites spread across the country, equipped with Soviet built P-37, PRV-13, P-18, P-14, P-19 and three ST-68 (36D6) radars; as well as the first indigenous radars START-1. They ground IFF interogator system used was L22 "Parola".

The Army operated all mobile SAM types (SA-6,-7,-8 and -9), together with a large number of quadruple 14.5 mm machine guns (MR-4), twin-barreled 30 mm guns (A-436 Model 1980) and outdated M1939, 85 mm guns. The only SPAAG in service were a number of BTR-40 equipped with 2x14,5 mm guns. Heavier 57 mm (S-60) radar guided anti-aircraft guns and the old 37mm ones were under the control of the AAT, being deployed around airbases and airports (usually 2-3 sites with 6-8 guns) and as close-in protection for the fixed SAM sites (one AAA site for each SAM site). Three army regiments were equipped with 15 SA-6 batteries, having each 5 batteries with 4 launchers and based at Bucharest (48 Reg.), Craiova (51 Reg.) and Medgidia (53 Reg.). A single SA-8 regiment (the 50th) was active with 16 launchers since mid-1989, based near Cluj-Napoca. All SAM and AAA units belonging to the Army were subordinated to the AAT from the operational point of view.

As of 1989, the Romanian armed forces had around 3000 SA-2,-3,-6,-7,-8 and -9 missiles at their disposal. Also in spring 1989, a few SPN-30 electronic warfare systems entered service withthe 147th Regiment based at Bucharest.

Romania was an important German ally in WWII, but changed sides on 23 August 1944. In accordance with agreements of the Jalta Conference, the country subsequently came within the Soviet sphere of influence, and was one of signatories of the Warsaw Pact.

The Romanian leadership managed to convince the Soviets to withdraw all troops from the country in June 1958. After that, Romania slowly adopted a form of nationalistic communism quite similar to that of neighboring Yugoslavia and became the least compliant of the Soviet satellites. In 1964 cooperation between the Romanian and USSR intelligence services virtually ended and relations with Moscowworsened especially since the dictator Nicolae Ceausescu established himself in power in 1965. Subsequently, in some matters, Romaniahas taken stands in direct opposition to Soviet policy, as in its continuing diplomatic relations with Communist China, Albania, and Israel.

Before long, the Romanian dictator was a thorn in the side of the Soviets. In August 1968, when the USSR and all other countries of the Warsaw Pact intervened in Czechoslovakia, Ceausescu denounced the invasion in a public speech, declaring it for a brutal interference in the internal affairs of a sovereign country. Romania was the only Warsaw Pact country not to participate, and subsequently it remained only a passive member of the Eastern Bloc: since August 1968, the Romanian ground forces did not participate in any Warsaw Pact exercise. Ceausescu showed strong tendencies on Romanian self-sufficiency, especially in regards of procuring armament for the military. Thus, while Romania was receiving substantial military equipment and training from the USSR in the 1950s, since the late 1960s it began searching for alternatives - in country, in the West and among non-aligned states. During the following years Ceausescu established an increasingly good image of himself and his country in the West, which was mostly due to his stand against the Soviets. Good relations with France (resulting in contracts for license production of Alouette III and Puma helicopters, as well as Renault cars), United Kingdom (resulting in contracts for license production of Rolls Royce Viper engines, BAC 1-11 and BN-2 Islander aircraft), Canada (resulting with the first non-Soviet nuclear reactor built in Eastern Europe), USA (with particularly good relations with Nixon’s administrations, Boeing 707 deliveries) were rising eyebrows in Kremlin time and again.

However, Ceausescu ruled Romania with help of the "Departamentul Securitatii Statului" (DSS) – the State Security Department, popularly known as “Securitatea” which was foremost busy controlling all aspects of public life in Romania through intelligence and repression. Securitatea was involved in espionage of literally everybody: like the former “Stazi” in East Germany, it maintained a wide net of informants, infiltrating economic structures, financial institutions, the executive and the legislature. Intercepting phone calls and placing "bugs" were also common practice. In this way, the DSS was perceived as being omni-present in every bureau, shop or home around the country and maintained order as much trough direct actions as trough the fear generated in the public by the fact that it could "listen" anything, anytime, and anybody could potentially be an informant.

In the 1980s, the Romanian regime became increasingly radical and isolated, with a very strong nationalist character. Ceausescu's clique developed an immense personality cult for him and his wife, surpassed in size and lack of realism only by the North Korean one. Like Ceausescu, Securitatea was hated in the public, but nobody was able to admit this openly, then the omni-presence of informants and agents ascertained that any dissident could be swiftly and decisively dealt with. At the political level, the communist regime saw the “Perestroika” efforts of the Soviet leader Gorbachev, almost as another Soviet intervention in Czechoslovakia; his drive to replace old Communist leaders of East European countries by reformers was considered dangerous.

By 1989, Romania was the last of the Warsaw Pact countries in which there were no reforms, quite on the contrary food and energy shortages began to resemble those found during a war or inside a third world country. The reformist Soviet leadership was not interested in having a potentially hostile regime on its borders; however it could not support an opposition or a reformative wing within the Romanian Communist Party (PCR) as there were none. Besides, the Securitatea would quite certainly learn about such efforts. But, if there was a popular uprising - even one sparked by foreign agents - the snowball effect was guaranteed due to the immense public discontent and in the case of a military repression, the Soviets would be provided with a reason to launch an invasion with the reasoning of “protecting Romanian people from their own dictator”.

Air Force

Romania has an old and proud aviation history, being one of the first countries where aircraft were imagined, built and flown, as well as a rich history of domestic aerospace industry. The first military air unit of the Romanian Army was established already in 1893, and was a balloon observation unit. As early as 1903, the first plans for an original aircraft were published, but it was not before 1906 that this plane was indeed flown by its inventor, Traian Vuia. Nevertheless, already four years later the first fan-jet powered plane in the world was built and flown – even if in an uncontrollable fashion – by Henri Coanda.

Romania became only the fifth nation world-wide to have an air force established as a separate military branch: the Romanian Flying Corps came into being already on 30 April 1913, as a branch subordinated directly to the Ministry of War, and having 80 pilots and 25 air observers at the time. It participated in the Second Balkan War shortly thereafter, in June-July 1913, flying observation and liaison sorties. During World War I, this corps actively participated in fighting against Austro-Hungarian, German and Bulgarian forces, even after most of the country was overrun by these, enjoying a very strong French support. The air arm experienced its “Golden Ages” in the 1920s and 1930s, when it was mainly equipped with domestic airplanes manufactured by no less but seven Romanian factories. Over 2.000 military and civilian airplanes were built by Romanian companies within 18 years.

In 1940, a number of German instructors arrived and the "Aeronautica Regala Romana" - ARR, Royal Romanian Aeronautics, was completely reorganized and then significantly increased, so that it participated very actively in the war against USSR, between 1941 and 1944. By the early 1944, however, the ARR was severely depleted and weakened due to the increasing number of Allied attacks against strategically important oilfields in Ploiesti area. On 20 August 1944, the Red Army breached the Romanian-German front in Moldova, and three days later a coup led by King Michael deposed the military dictator Antonescu and his cabinet, leading to fierce fighting between the Romanians and Germans, on 24 and 25 August, involving both air forces. When the Soviets finally reached Bucharest, on 30 August, the south of the country was already free of all German troops: the rest of these retreated behind Transylvanian mountains. Thus, the Romanians changed sides on their own, right before being overrun by the Soviets. Afterwards, the ARR actively fought against Germany and Hungary during campaigns over Romanian, Hungarian, Czechoslovak and Austrian territories.

In 1947, the prefix “Royal” was dropped and the Air Force, “Fortele Aeriene ale Republicii Populare Romane” – Air Force of the Popular Republic of Romania – was reorganized along Soviet lines. On 10 August 1950, a new national insignia derived from the Red Star design was adopted. The first Yakovlev Yak-23 and Yak-17UTI fighter jets were supplied in 1951, followed by MiG-15s, the next year, and MiG-17s and Il-28s in 1955, when the official designation of the air force was changed to "Aviatia Militara" (AvM) - Military Aviation. In 1958, the first supersonic fighter – MiG-19 – entered service, followed by MiG-21F-13s, four years later. In 1956 the first helicopter unit was established, flying 4 Soviet-made Mil Mi-4s and, starting from 1962, also SM-2 and SM-1s – the Polish made variants of the Mi-1.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Romania re-established its aviation industry and obtained licence for production of some Western types, including Aérospatiale SA.316B Alouette III, SA.330 H/L Puma, Britten-Norman BN-2 Islander and BAC 1-11. Simultaneously, a strike fighter was developed and manufactured in cooperation with Yugoslavia, in the frame of the YUROM project, that resulted in the IAR-93/J-22 Orao – the only non-Soviet fighter-bomber ever built and flown in an air force of a (at least officially) Warsaw Pact member state. Experience accumulated in these programs permitted the development and building of an indigenous jet trainer, the IAR-99.

As of 1989, the AvM had approximately 32.000 personnel, of which less than one third were conscripts. The air force had an inventory of 512 combat aircraft, and was also responsible for transport, reconnaissance and helicopters, with the primary mission of defending the country against invasion while protecting and supporting the ground forces and navy. Theoretically divided into three tactical divisions, the AM's basic organizational structure was the Regiment, housed by a single base. The commander in chief in December 1989 was Gen. Iosif Rus.

As far as jets are concerned, they mainly flew Soviet-made MiG-21s and MiG-23s, but many MiG-15s and a few MiG-17 were still available for ground attack, as well as a large number of IAR-93s. Finally, on 21 December 1989, the first 4 MiG-29s arrived in Romania ferried by Soviet pilots (MiG-29 A serials 41, 46 and MiG-29 UB serials 15 and 23), but the first flights with Romanian pilots began only in April 1990. The helicopter fleet consisted of roughly 100 each IAR-316B Alouette III and IAR-330L Puma, plus less than 30 Mi-8T/PS. The lack of a dedicated attack/anti-tank helicopter was partially suplemented by the posibility to arm all helicopter types mentioned above - mostly with unguided rockets. Altough all jet fighter units were trained, besides interception and air combat, for ground attack, only two regiments were designated fighter-bomber regiments and trained specifically for ground attack and CAS.

The “Aurel Vlaicu Flight Academy” had a large number of training aircraft based on three airfields in close proximity to each other, as follows:

Focsani AB (grass airfield)

19 School Liaison Regiment

- IAR-823 and Yak-52

Boboc AB

20 School Fighter-Bomber Regiment

- IAR-823, L-29, L-39ZA and IAR-99

Buzau AB (grass airfield)

21 School Transport Regiment

- An-2R/T and IAR-316B

The operational units were:

Ianca AB

49 Fighter-Bomber Regiment

- 1/49 Fighter-Bomber Squadron, IAR-93MB/DC (not yet operational)

- 2/49 Fighter-Bomber Squadron, MiG-15 (S-102)

- 3/49 Fighter-Bomber Squadron, MiG-15 (S-102)

Mihail Kogalniceanu (near the Black Sea shore)

57 Fighter Regiment

- 1/57 Fighter Squadron, MiG-29A/29UB (not yet operational, replacing MiG-21M/UM)

- 2/57 Fighter Squadron, MiG-23MF/UB

- 3/57 Fighter Squadron, MiG-23MF/UB

- 143 Pilotless Reconnaissance Squadron, VR-3 Reis (Tu-143)

Turnisor AB (Sibiu)

58 Helicopter Regiment

- 1/58 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-330L

- 2/58 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-316B

Ghimbav Airfield/ICA Brasov (Brasov)

58 Helicopter Regiment (det.)

- 1/58 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-316B

Tuzla AB (near the Black Sea shore)

59 Helicopter Regiment

- 1/59 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-330L

- 2/59 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-316B

Tecuci AB

60 Helicopter Regiment

- 141 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-330L

- 183 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-316B

Boteni AB (also known as Titu)

61 Helicopter Regiment

- 1/61 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-330L

- 2/61 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-316B

Craiova AB

67 Fighter-Bomber Regiment

- 1/67 Fighter-Bomber Squadron, IAR-93 A/MB/B/DC

- 2/67 Fighter-Bomber Squadron, IAR-93 A/MB/B/DC

- 3/67 Fighter-Bomber Squadron, MiG-15 (S-102), MiG-17F/PF

Campia Turzii AB (also known as Luna)

71 Fighter Regiment

- 1/71 Fighter Squadron, MiG-21MF/UM

- 2/71 Fighter Squadron, MiG-21M/UM

- 3/71 Fighter Squadron, MiG-21M/UM

Caransebes AB

73 Helicopter Regiment

- 1/73 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-330L

- 2/73 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-316B

Fetesti AB (also known as Borcea)

86 Fighter Regiment

- 1/86 Fighter Squadron, MiG-21MF/UM

- 2/86 Fighter Squadron, MiG-21PFM/U/US

- 3/86 Fighter Squadron, MiG-21PFM/U/US

- 38 Reconaissance Squadron, Harbin H-5R/B, HJ-5

Otopeni AB (Bucharest)

50th Aerial Transport Flotilla An-24V/RV/R/RT, An-26, An-30, BN-2 Islander, ROMBAC 1-11, Il-18, Boeing 707-3K1C; IAR-316B, IAR-330L, Mi-8T/PS, Mi-17, SA365N Dauphin 2

Deveselu AB

91 Fighter Regiment

- 1/91 Fighter Squadron, MiG-21MF-75/UM

- 2/91 Fighter Squadron, MiG-21MF/UM

- 3/91 Fighter Squadron, MiG-21PFM/UM

Alexeni AB

94 Helicopter Regiment

- 1/94 Helicopter Squadron, Mi-8T

- 2/94 Helicopter Squadron, IAR-316B

- 131 Helicopter Navigator Training Squadron, IAR-316B, IAR-330L, Mi-8T

Giarmata AB (Timisoara)

93 Fighter Regiment

- 1/93 Fighter Squadron, MiG-23MF/UB

- 2/93 Fighter Squadron, MiG-21MF-75/UM

- 3/93 Fighter Squadron, MiG-21MF-75/UM

- 31 Reconnaissance Squadron MiG-21R/UM

Bacau AB

CIAv - Centrul de Instructie a Aviatiei (acting as operational conversion unit)

- 1st Squadron, MiG-21M/UM

- 2nd Squadron, MiG-21PFM/US

- 3rd Squadron, MiG-21PF/U (to be replaced by MiG-21M/UM displaced from Mihail Kogalniceanu by MiG-29s)

The national air defence system (AAT) was under a different command, being responsible for the radar network and fixed SAM sites, led by Gen. Mircea Mocanu. The main defensive asset was the SA-2 (S-75M3 Volhov) with 5Ia23 type missiles, deployed in 13 sites protecting the Bucharest - Ploiesti - Brasov area. Four SA-3 batteries (S-125 M1A Neva) armed with 5V27D (V-601) missiles were also available, being deployed to form an inner ring to protect the capital. The area around Bucharest and Ploiesti belonged to the 1st SAM Brigade, while Brasov with its vital industries and helicopter factory was defended by the 11th SAM Regiment. Another two SA-2 regiments were available, garrisoned at Galati and Resita (the latter with four batteries deployed in the Deva-Huneadoara-Orastie area). The early warning network consisted of 36 radar sites spread across the country, equipped with Soviet built P-37, PRV-13, P-18, P-14, P-19 and three ST-68 (36D6) radars; as well as the first indigenous radars START-1. They ground IFF interogator system used was L22 "Parola".

The Army operated all mobile SAM types (SA-6,-7,-8 and -9), together with a large number of quadruple 14.5 mm machine guns (MR-4), twin-barreled 30 mm guns (A-436 Model 1980) and outdated M1939, 85 mm guns. The only SPAAG in service were a number of BTR-40 equipped with 2x14,5 mm guns. Heavier 57 mm (S-60) radar guided anti-aircraft guns and the old 37mm ones were under the control of the AAT, being deployed around airbases and airports (usually 2-3 sites with 6-8 guns) and as close-in protection for the fixed SAM sites (one AAA site for each SAM site). Three army regiments were equipped with 15 SA-6 batteries, having each 5 batteries with 4 launchers and based at Bucharest (48 Reg.), Craiova (51 Reg.) and Medgidia (53 Reg.). A single SA-8 regiment (the 50th) was active with 16 launchers since mid-1989, based near Cluj-Napoca. All SAM and AAA units belonging to the Army were subordinated to the AAT from the operational point of view.

As of 1989, the Romanian armed forces had around 3000 SA-2,-3,-6,-7,-8 and -9 missiles at their disposal. Also in spring 1989, a few SPN-30 electronic warfare systems entered service withthe 147th Regiment based at Bucharest.