boomslang

SENIOR MEMBER

- Joined

- Oct 10, 2013

- Messages

- 2,990

- Reaction score

- -9

- Country

- Location

China's censors are cracking down on the online news industry

Since Chinese President Xi Jinping came to power in late 2012, Communist authorities have gradually tightened control on freedom of expression. (Koca Sulejmanovic / European Pressphoto Agency)

Julie Makinen

In a further attempt to tighten censorship, China this week said it was investigating eight of the nation’s high-profile Internet companies for “serious violations” of rules on who may report and publish news, ordering them to shut down or “clean up” their websites immediately.

Just as millions of Americans turn to Google and Yahoo for their headlines, Chinese likewise have increasingly come to rely on websites including Sina, Tencent and NetEase for daily information. In recent years, major Internet companies have gone beyond carrying dispatches from the official New China News Agency, People’s Daily and other state-authorized information providers to hiring their own journalists to do original reporting.

That activity has long been conducted in a regulatory gray area — the government, for example, has not issued official media credentials to reporters from such outlets. Nevertheless, the boom in Internet news lured many well-respected Chinese journalists away from traditional outlets to the online world. And regulators for years tolerated the phenomenon, seeking to manage it with orders directing websites to remove certain “sensitive” stories from their sites and notices outlining which topics were off-limits.

Some of the outlets managed to push the boundaries. NetEase’s Landmark section, for example, wrote about a woman forced by the government to have an abortion, and Phoenix’s Serious News channel tackled topics such as devout Muslims in the western region of Xinjiang. Others wrote about environmental issues and corrupt officials.

For a while, it all seemed to be part of a trend toward greater openness that began with the run-up to the 2008 Beijing Olympics and the rapid spread of the Internet and mobile phones. But since Chinese President Xi Jinping came to power in late 2012, Communist authorities have engaged in a gradual tightening of control.

A lot of economists have been warned not to say anything negative about the economy. — Beijing-based journalism professor

First came greater interference with newspapers like Southern Weekend, which had delved deep into social issues and run edgy editorials. Then came orders to close the social media accounts of “big voices” or “Big V’s” — online commentators with large followings. This year, Xi himself toured major state-run media outlets and proclaimed that all media “must be surnamed party,” and must “love the party, protect the party and serve the party.”

“According to the prevailing official view of media supervision in the Xi era, critical reporting has gotten out of hand over the past two decades as a result of social and technological transformations,” David Bandurski of the China Media Project at the University of Hong Kong wrote in an analysis last month. “What the [party] needs now is to re-appropriate supervision — to subject it, in other words, to rigorous party supervision.”

Yet what exactly prompted this week’s crackdown on the online portals remains unclear. Some Chinese journalists believe it stemmed from an unfortunate typo this month at Tencent, which said Xi gave “an important speech in a furious manner” instead of “delivered an important speech.”

Others believe it may be all part of an effort by China’s new Internet czar, Xu Lin — who took over less than a month ago — to convey a decisive and tough image from the get-go.

“The production of news by these news websites themselves has always been half-legal in China. The Cyberspace Administration used to turn a blind eye,” said Wen Tao, a former reporter at Phoenix’s Serious News. “There’s always a ritual for the new leader in China to apply strict measures to establish his authority.”

Still others believe it’s part of a predictable cycle of heightened strictures ahead of a major party gathering in the fall of 2017 at which top leaders for the next five years will be confirmed.

“Things will continue to get stricter until next year’s Party Congress,” predicted one Beijing-based journalism professor who asked not to be identified because the topic was “very sensitive.” “Even the controls on economic news will be stricter — a lot of economists have been warned not to say anything negative about the economy.”

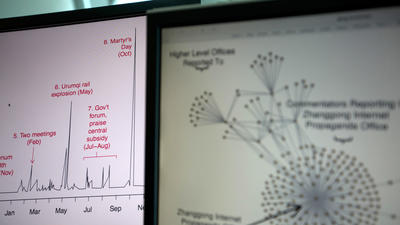

Who needs censorship? Chinese government-backed users flood social media

In its notice about investigating the internet companies, the Cyberspace Administration said that the companies’ “ideological thinking was not deep enough” and that their “blind pursuit of economic interests” had led to problems.

Staff members at two other targeted news websites, speaking on condition of anonymity for fear they could lose their jobs, said this week’s order had left them in a state of suspended animation, unclear whether their departments would be eliminated or reassigned to do other work. The writers could, for instance, be redirected to softer subjects such as entertainment or sports. “There is still space to do work on those subjects,” said the journalism professor.

But what the lasting effect would be remained unclear. Chinese leaders including Xi himself and Premier Li Keqiang have been strongly touting the Internet and information technology as key drivers of growth, noting that these sectors have been creating jobs by the millions in China even as other sectors of the economy, such as manufacturing, slow.

“I don’t think the online news industry will be limited by this order in the long term,” said Wen. “There has always been a game between the censors and the censored. The Internet is experiencing explosive growth. … This is only a technical change, not a trend changer.”

Nicole Liu and Yingzhi Yang in The Times’ Beijing Bureau contributed to this report.

Since Chinese President Xi Jinping came to power in late 2012, Communist authorities have gradually tightened control on freedom of expression. (Koca Sulejmanovic / European Pressphoto Agency)

Julie Makinen

In a further attempt to tighten censorship, China this week said it was investigating eight of the nation’s high-profile Internet companies for “serious violations” of rules on who may report and publish news, ordering them to shut down or “clean up” their websites immediately.

Just as millions of Americans turn to Google and Yahoo for their headlines, Chinese likewise have increasingly come to rely on websites including Sina, Tencent and NetEase for daily information. In recent years, major Internet companies have gone beyond carrying dispatches from the official New China News Agency, People’s Daily and other state-authorized information providers to hiring their own journalists to do original reporting.

That activity has long been conducted in a regulatory gray area — the government, for example, has not issued official media credentials to reporters from such outlets. Nevertheless, the boom in Internet news lured many well-respected Chinese journalists away from traditional outlets to the online world. And regulators for years tolerated the phenomenon, seeking to manage it with orders directing websites to remove certain “sensitive” stories from their sites and notices outlining which topics were off-limits.

Some of the outlets managed to push the boundaries. NetEase’s Landmark section, for example, wrote about a woman forced by the government to have an abortion, and Phoenix’s Serious News channel tackled topics such as devout Muslims in the western region of Xinjiang. Others wrote about environmental issues and corrupt officials.

For a while, it all seemed to be part of a trend toward greater openness that began with the run-up to the 2008 Beijing Olympics and the rapid spread of the Internet and mobile phones. But since Chinese President Xi Jinping came to power in late 2012, Communist authorities have engaged in a gradual tightening of control.

A lot of economists have been warned not to say anything negative about the economy. — Beijing-based journalism professor

First came greater interference with newspapers like Southern Weekend, which had delved deep into social issues and run edgy editorials. Then came orders to close the social media accounts of “big voices” or “Big V’s” — online commentators with large followings. This year, Xi himself toured major state-run media outlets and proclaimed that all media “must be surnamed party,” and must “love the party, protect the party and serve the party.”

“According to the prevailing official view of media supervision in the Xi era, critical reporting has gotten out of hand over the past two decades as a result of social and technological transformations,” David Bandurski of the China Media Project at the University of Hong Kong wrote in an analysis last month. “What the [party] needs now is to re-appropriate supervision — to subject it, in other words, to rigorous party supervision.”

Yet what exactly prompted this week’s crackdown on the online portals remains unclear. Some Chinese journalists believe it stemmed from an unfortunate typo this month at Tencent, which said Xi gave “an important speech in a furious manner” instead of “delivered an important speech.”

Others believe it may be all part of an effort by China’s new Internet czar, Xu Lin — who took over less than a month ago — to convey a decisive and tough image from the get-go.

“The production of news by these news websites themselves has always been half-legal in China. The Cyberspace Administration used to turn a blind eye,” said Wen Tao, a former reporter at Phoenix’s Serious News. “There’s always a ritual for the new leader in China to apply strict measures to establish his authority.”

Still others believe it’s part of a predictable cycle of heightened strictures ahead of a major party gathering in the fall of 2017 at which top leaders for the next five years will be confirmed.

“Things will continue to get stricter until next year’s Party Congress,” predicted one Beijing-based journalism professor who asked not to be identified because the topic was “very sensitive.” “Even the controls on economic news will be stricter — a lot of economists have been warned not to say anything negative about the economy.”

Who needs censorship? Chinese government-backed users flood social media

In its notice about investigating the internet companies, the Cyberspace Administration said that the companies’ “ideological thinking was not deep enough” and that their “blind pursuit of economic interests” had led to problems.

Staff members at two other targeted news websites, speaking on condition of anonymity for fear they could lose their jobs, said this week’s order had left them in a state of suspended animation, unclear whether their departments would be eliminated or reassigned to do other work. The writers could, for instance, be redirected to softer subjects such as entertainment or sports. “There is still space to do work on those subjects,” said the journalism professor.

But what the lasting effect would be remained unclear. Chinese leaders including Xi himself and Premier Li Keqiang have been strongly touting the Internet and information technology as key drivers of growth, noting that these sectors have been creating jobs by the millions in China even as other sectors of the economy, such as manufacturing, slow.

“I don’t think the online news industry will be limited by this order in the long term,” said Wen. “There has always been a game between the censors and the censored. The Internet is experiencing explosive growth. … This is only a technical change, not a trend changer.”

Nicole Liu and Yingzhi Yang in The Times’ Beijing Bureau contributed to this report.

i have to thank Erdogan, just too hilarious speaking of timing

i have to thank Erdogan, just too hilarious speaking of timing