This is going to be a long post composed of two articles that are highly technical in nature. The takeaway: there are troubling signs that liquidity in a critical segment of the treasuries market is drying up, primarily because of increasingly stringent capital requirements for banks. If it gets significantly worse, we could start to see severe disruptions in the US credit market. It's too soon to say if this will get to the level of a Lehman Brothers crisis, but keep an eye on it.

Bond Anxiety in $1.6 Trillion Repo Market as Failures Soar - Bloomberg

Print Back to story

Bond Anxiety in $1.6 Trillion Repo Market as Failures Soar

By Liz Capo McCormick - Jul 7, 2014

In the relative calm that is the market for U.S. Treasuries, a sense of unease over a vital cog in the financial system’s plumbing is beginning to rise.

The Federal Reserve’s bond purchases combined with demand from banks to meet tightened regulatory requirements is making it harder for traders to easily borrow and lend certain desired securities in the $1.6 trillion-a-day market for repurchase agreements. That’s causing such trades to go

uncompleted at some of the highest rates since the financial crisis.

Disruptions in so-called repos, which Wall Street’s biggest banks rely on for their day-to-day financing needs, are another unintended consequence of extraordinary central-bank policies that pulled the economy out of the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression. They also belie the stability projected by bond yields at about record lows.

“You have a little bit of a perfect storm here,” said

Stanley Sun, a New York-based interest-rate strategist at Nomura Holdings Inc., one of the 22 primary dealers that bid at Treasury auctions, in a telephone interview June 30.

Smoothly functioning repo trading is vital to the health of markets. The fall of Bear Stearns Cos., which was taken over by JPMorgan Chase & Co. in 2008 after an emergency bailout orchestrated by the Fed, and the collapse of Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc., whose bankruptcy in September of that year plunged markets into a crisis, were hastened after they lost access to such financing.

Cash Transaction

In a typical repo, a dealer needing short-term cash often borrows money from another dealer, a hedge fund or a money-market fund, putting up Treasuries as collateral. The cash lender can then use the securities to complete other trades, such as to close out short positions where it needs to deliver bonds.

Negative rates happen when certain Treasuries are in such high demand or short supply that lenders of cash are actually paying collateral providers interest so they can obtain the needed securities. Traders said that is a big reason why repo rates on desired Treasuries have recently gotten as low as negative 3 percent.

Now, more repo trades are going uncompleted, or failing, because it’s either too difficult or expensive for the borrower to obtain and deliver Treasuries. Such failures to deliver Treasuries have averaged $65.6 billion a week this year, reaching as much as $197.6 billion in the week ended June 18, Fed data show.

Uncompleted trades averaged $51.6 billion in 2013, and $28.8 billion in 2012, according to the Fed. In those cases, the borrower pays a 3 percent penalty.

Liquidity Issues

“The effect of all the collateral issues we see now is an indication of not so much how things are, but how bad things will be when you really need liquidity,” said Jeffrey Snider, chief investment strategist at West Palm Beach, Florida-based Alhambra Investment Partners LLC, in a telephone interview June 30. “That’s when you get into potentially dire situations.”

The conditions for repo stress were on display last month. The 2.5 percent note due in May 2024 reached negative 3 percentage points in repo in the days preceding a June 11 Treasury auction of $21 billion in notes to finance government operations.

Dealer Constraints

Repo rates have been most prone to go negative, a situation known as specials in the market, in the days preceding an auction as traders who previously sold the debt seek to buy the securities to cover those positions.

In this week’s note and bond sales, the U.S. plans to auction $27 billion of three-year Treasuries tomorrow, $21 billion of 10-year debt on July 9 and $13 billion of 30-year securities July 10.

Signs of dysfunction are coming at a sensitive time for markets. The Fed is paring its stimulus and futures show traders expect the central bank may start raising interest rates in the middle of next year.

Treasury notes declined today after Goldman Sachs Group Inc. brought forward its forecast for the Fed to increase interest rates to the third quarter of 2015, from a previous estimate of the first three months of 2016. The three-year yield climbed one basis point to 0.97 percent at 1:31 p.m. New York time.

Available Securities

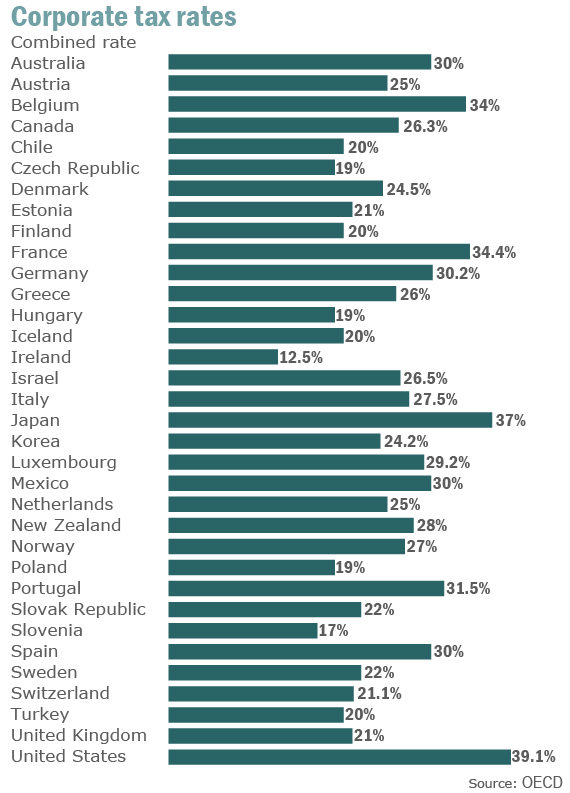

The concern is that dealers, which have pared inventories to meet more-stringent capital requirements required by the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act mandated by the Volcker Rule and Basel III, won’t have as much capacity to handle any surge in volumes or volatility.

Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association data show the average daily trading volume in Treasuries has fallen to $504 billion this year from $570 billion in 2007, even though the amount outstanding has risen to more than $12 trillion from $4.34 trillion.

Bank of America Merrill Lynch’s

MOVE Index, a measure of expectations for swings in bond yields based on volatility in over-the-counter options on Treasuries maturing in two to 30 years, reached 52.7 percent on June 30, almost a record low.

The Fed is partly to blame. Through its policy of quantitative easing, it now owns about 20 percent of all Treasuries, or $2.39 trillion. Banks hold $547 billion of Treasury and agency-related debt.

In addition, the Fed’s holdings have shifted in ways that leave fewer central-bank-owned Treasuries available to be borrowed. The shifts were caused by

Operation Twist during the November 2011 to December 2012 period when the Fed sold shorter-dated Treasuries and bought more bonds, plus self-imposed central-bank restrictions on holdings of specific maturities.

Stimulus Withdrawal

The Fed’s lack of certain holdings “appears to be driving the surge in fails, which has been concentrated in the on-the-run five- and 10-year notes,”

Joe Abate, a money-market strategist in New York at primary dealer Barclays Plc, wrote in a note to clients on June 27. On-the-run refers to the most recently issued Treasuries of a specific maturity.

While the Fed has sought to cut risk in the repo market since the crisis, it still sees the chance that rapid sales of securities, known as fire sales, could disrupt the financial system. Fails reached a record $2.7 trillion in October 2008.

Repos are also important to the Fed because it has been testing a program in the market that is seen as a potential tool to withdraw some of its unprecedented monetary stimulus.

Eric Pajonk, a spokesman at the New York Fed, decline to comment on the Fed’s reaction to the movements in recent weeks in the repo market.

Supply Falls

The amount of securities financed daily in the

tri-party repo market has declined 18 percent to an average $1.60 trillion in June, from $1.96 trillion in December 2012, data compiled by the Fed show. In a tri-party agreement, one of two clearing banks functions as the agent for the transaction and holds the security as collateral. JPMorgan and Bank of New York Mellon Corp. serve as the industry’s clearing banks.

Another difficulty in the repo market has been the decline in Treasury bill supply, with the U.S. having sold $264 billion fewer short-term bills in the April-through-June period than those that matured, according to

John Canavan, a fixed-income strategist at Stone & McCarthy Research Associates in Princeton, New Jersey.

“The repo market itself provides lubricant to the entire Treasury market,” Canavan said in a July 3 telephone interview. “Bills are a key lubricant to the repo market, and the supply of bills has fallen sharply. If this situation were to continue longer term, it would be a more substantial problem.”

Don’t freak out about UST fails (yet) | FT Alphaville

Don’t freak out about UST fails (yet)

Izabella Kaminska Comment |

talking about the spike in repo fails.

But here’s the thing. Repo fails need to be seen in context.

Yes, this chart from BoAML makes the recent June spike look significant:

And BoAML Brian Smedley and team do advise to take the recent spate of fails seriously:

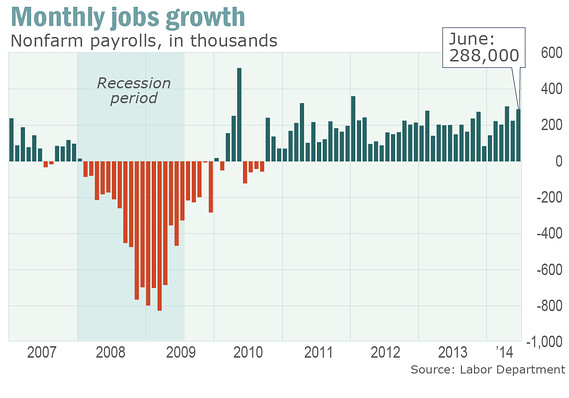

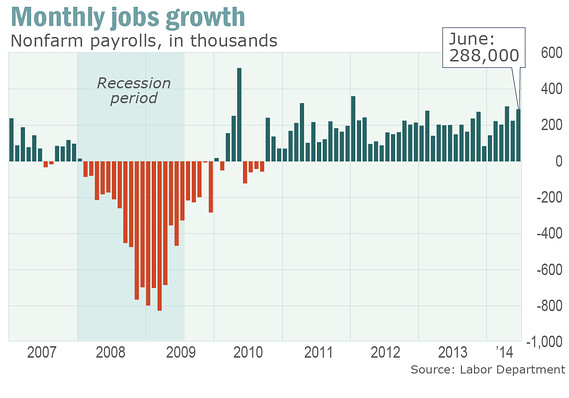

In the past month various issues across the US Treasury curve have traded special in the repo market, indicating that the demand to borrow the securities from shorts has increased relative to the supply of bonds being lent by longs. In our view, analyzing the causes of the recent repo specialness and the associated increase in settlement fails reveals information about Treasury market conditions that is relevant to investors more broadly. In particular, we believe increased specialness could be symptomatic of lingering fast money shorts and sizable central bank buying, as well as regulatory constraints on dealers’ ability to intermediate in the repo market. These factors pose risks to our short duration bias, and likely help explain why rates have declined since last week’s better-than-expected June employment report.

However, once again, the context is important.

The real story, we would argue, is that US Treasury fails have been an unappreciated market phenomenon

ever since 2008 onwards. Back then fails blew out, and when repo rates (what might also be called the private collateralised liquidity rate) dropped through the floor in special issues, this is when the Fed took serious action.

The urgency was related to the fact that negative repo rates in private collateral markets reflected limited Federal Reserve control over short-term

private rates, and the sort of crowding out of safe assets that could later pose serious deflationary feedback loops.

In the first instance, the Fed’s Interest On Excess Reserves (IOER) policy and treasury swapping facilities helped to ease matters significantly. However, when fails continued despite the introduction of such liquidity floors (because not all institutions had access to these facilities) the Fed introduced something known as a 3 per cent fails charge.

This, as it happens, was extremely successful at suspending the fails drama in the Treasury market, leading to a general perception that the fails issue was no longer a problem.

But another way of looking at it is that all the 3 per cent charge did was push the pressure elsewhere, whilst disguising the market disruption in the UST collateral markets.

So here’s the thing. Yes, in the context of the wider fails problem of 2008 the recent June spike looks insignificant. But another way to think about this is that the fails are happening

despite the presence of the 3 per cent fails charge and

despite the presence of the Fed’s new Reverse Repo Facility, which should also have eased pressure in the market.

As BoAML notes:

The recent increase in fails is important, but not alarming. Prior to May 2009, when the 3% fails charge was introduced, widespread fails were more common and more severe than recent experience. During a particularly dysfunctional period in 2008, primary dealer fails to deliver and receive Treasuries reached nearly US$2.7tn each.

Here, meanwhile, is repo expert

Scott Skyrm on the fails charge issue:

Not covering shorts was actually quite common in the past for periods of time when there were protracted shortages. It all came to a head in October 2008 when securities were pulled from the market, the Fed dropped overnight rates down to near 0.0%, and counterparties stopped trading with each other. It was the perfect storm in the repo market and fails shot up to an all-time record high of $5.06 trillion on October 15, 2008. People realized there needed to be a cost of failing in the Fed’s new 0.0% interest rate environment. About 7 months later, the Fail charge was introduced. At 0.0% rates, the Fail Charge is 300 basis points which makes the break-even cost for not covering a short the equivalent of -3.00%. These days, when repo rates get near or below -3.00%, dealers will not cover their shorts. It’s also why you rarely see repo rates below -3.00%

According to BoAML, the problem is thus not a general shortage of collateral in the market but rather the lack of a very specific type of Treasury stock — the sort being demanded to cover shorts — at the Fed, which has until now been able to lend out securities that have been overly scarce to ease such scrambles.

As they noted this week:

But because the Fed is only buying issues with more than four years to maturity in QE3, and because issues trading special in repo are excluded from purchases (so as to avoid exacerbating specialness), the Fed does not always have on-the-runs to lend. Moreover, Fed purchases under QE3 will soon come to an end, and there are no significant Treasury reinvestments in the Fed portfolio until 2016 as a result of Operation Twist. This will increase the likelihood of on-the-runs trading special, and will provide more opportunities for dealers to trade specific issues in the repo market, which is generally good news. The bad news is that the bid-ask spreads that dealers will need to earn to justify the balance sheet usage are on the rise, due to growing regulatory costs, and we think that will likely mean more dislocations in the Treasury market.

Skyrm, meanwhile, put the blame on the change in the composition of the Fed portfolio since Operation Twist:

Another outlet blamed the increase in fails on QE. I can assure you, QE is not causing the fails, and let’s be clear, I’d be one of the first to criticize QE if it did. Remember, the Fed has a securities lending program, so the securities it purchases in the market are still available in the repo market. However, I did read one interesting point. Under Operation Twist, the Fed sold their short-term securities and purchased long-term securities and the Fed does not own any securities that mature until 2016. Operation Twist skewed the Fed’s holdings away from the short-end. Thus, potentially less supply in the short-end of the market.

But whilst Skyrm concludes that this shouldn’t be anything to panic about because securities will eventually be tempted back into the market via attractive collateral borrowing rates, the BoAML analysts are less optimistic. This is because, despite the prospect of more supply coming to the market, they believe regulatory burdens will only shrink lendable supply in the coming months.

As they conclude:

The Fed remains concerned about financial stability risks posed by short-term wholesale funding markets, particularly repo. Chair Janet Yellen has noted that while the Basel III framework would help address the Fed’s concerns about liquidity risk, it does not go far enough. As such, she said that “Federal Reserve staff are actively considering additional measures that could address… residual risks in the short- term wholesale funding markets.” Among these measures are requirements that large firms hold even greater amounts of capital, stable funding or highly liquid assets based on their use of short-term wholesale funding. Also under consideration is a proposal to set minimum margin requirements (haircuts) on repo and other securities financing transactions. Increased capital charges for repo transactions would likely further reduce liquidity in the repo market, in our view, potentially leading to increased specialness of on-the-runs and an increase in settlement fails going forward. This is likely to richen on-the-runs versus off-the-runs in the cash market, and increase the cost of borrowing on-the-runs in repo in order to establish short positions.

To us that suggests the financial plumbing of the system will become a key concern of the Fed, and one which most of its new extraordinary policies will be aimed at. Especially given that, according to the above, even a balance sheet unwinding would be unlikely to solve the problem since it’s not the Fed’s hoarding of securities which is really causing market tightness. The tightness is caused by ongoing hoarding in private markets — potentially exacerbated by new regulatory reforms regarding liquid capital buffers.

JIA) dipped immediately after the Fed minutes were released but quickly moved higher. Bond yields (ICAPSD:10_YEAR) also had a brief move higher after the report.

JIA) dipped immediately after the Fed minutes were released but quickly moved higher. Bond yields (ICAPSD:10_YEAR) also had a brief move higher after the report.