IrbiS

FULL MEMBER

- Joined

- Jul 21, 2011

- Messages

- 1,298

- Reaction score

- 7

- Country

- Location

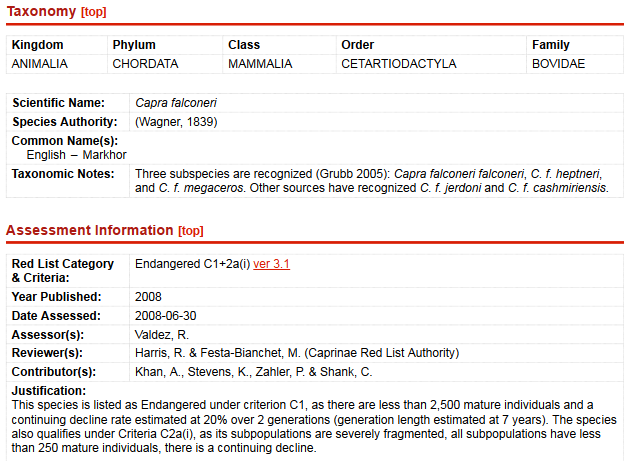

MAR-KHOR / Snake Eater ( Capra falconeri )

Markhor is a species of wild goat inhabiting Northeast Afghanistan, Pakistan, Azad Kashmir and Indian-occupied Jammu & Kashmir, Southern Tajikistan and Southern Uzbekistan. It eats grasses and leaves. Females gestate for 135-170 days and give birth typically to 1-2 kids. Animals are sexually mature at 18-30 months, and live 12-13 years. Predators include the wolf, snow leopards, and lynx.

Markhor is the National Animal of Pakistan and listed as an Endangered Species. Some 2,500 mature individuals are left in the wild and population trend is on the decline.

Etymology

The colloquial name is thought by some to be derived from the Persian word mar, meaning snake, and khor, meaning "eater", which is sometimes interpreted to either represent the species' ability to kill snakes, or as a reference to its corkscrewing horns, which are somewhat reminiscent of coiling snakes. According to folklore (Explanation by Shah Zaman Gorgani), the markhor has the ability to kill a snake and eat it. Thereafter, while chewing the cud, a foam-like substance comes out of its mouth which drops on the ground and dries. This foam-like substance is sought after by the local people, who believe it is useful in extracting snake poison from snake bitten wounds.

Physical description

Markhor stand 65 to 115 centimetres (26 to 45 in) at the shoulder, 132 to 186 centimetres (52 to 73 in) in length and weigh from 32 to 110 kilograms (71 to 243 lb). They have the highest maximum shoulder height among the species in the genus Capra, but is surpassed in length and weight by the Siberian Ibex. The coat is of a grizzled, light brown to black colour, and is smooth and short in summer, while growing longer and thicker in winter. The fur of the lower legs is black and white. Markhor are sexually dimorphic, with males having longer hair on the chin, throat, chest and shanks. Females are redder in colour, with shorter hair, a short black beard, and are maneless. Both sexes have tightly curled, corkscrew-like horns, which close together at the head, but spread upwards toward the tips. The horns of males can grow up to 160 cm (64 inches) long, and up to 25 cm (10 inches) in females. The males have a pungent smell, which surpasses that of the domestic goat.

Behavior

Markhor are adapted to mountainous terrain, and can be found between 600 and 3,600 meters in elevation. They typically inhabit scrub forests made up primarily of oaks (Quercus ilex), pines (Pinus gerardiana), and junipers(Juniperus macropoda). They are diurnal, and are mainly active in the early morning and late afternoon. Their diets shift seasonally: in the spring and summer periods they graze, but turn to browsing in winter, sometimes standing on their hind legs to reach high branches. The mating season takes place in winter, during which the males fight each other by lunging, locking horns and attempting to push each other off balance. The gestation period lasts 135–170 days, and usually results in the birth of one or two kids, though rarely three. Markhor live in flocks, usually numbering nine animals, composed of adult females and their young. Adult males are largely solitary. Adult females and kids comprise most of the markhor population, with adult females making up 32% of the population and kids making up 31%. Adult males comprise 19%, while subadults (males aged 2–3 years) make up 12%, and yearlings (females aged 12–24 months) make up 9% of the population. Their alarm call closely resembles the bleating of domestic goats. Early in the season the males and females may be found together on the open grassy patches and clear slopes among the forest. During the summer, the males remain in the forest, while the females generally climb to the highest rocky ridges above

Geographic Range

This species is found in northeastern Afghanistan, southwest Jammu and Kashmir, northern and central Pakistan, southern Tajikistan and southern Uzbekistan (Grubb, 2005). It ranges in elevation from 600 to 3,600 m asl.

Capra falconeri falconeri ( Astor / Pir Panjal Markhor )

Within Afghanistan, it is historically been limited to the east in the high mountainous, monsoon forests of Laghman and Nuristan. Within India, markhor is restricted to part of the Pir Panjal range in southwestern Jammu and Kashmir (Ranjitsinh et al. 2005, Bhatnagar et al. 2007). Populations are scattered throughout this range starting from just east of the Banihal pass (50 km from the Chenab river) on the Jammu-Srinagar highway westward to the disputed border with Pakistan. Populations are known from recent surveys still to occur in catchments of the Limber and Lachipora rivers in the Jhelum Valley Forest Division, and around Shupiyan to the south of Srinagar. In Pakistan, Schaller and Khan (1975) considered the former Astor markhor (C. f. falconeri) and Kashmir markhor (C. f cashmiriensis) to be one subspecies – the flare-horned markhor. The distribution map given by Schaller and Khan (1975) seems still valid for this markhor, though the populations within the large range along the Indus have probably since decreased. Markhor is mainly confined to the Indus and its tributaries, as well as to the Kunar (Chitral) river and its tributaries. Along the Indus, it inhabits both banks from Jalkot (District Kohistan) upstream to near the Tungas village (District Baltistan), with Gakuch being its western limit up the Gilgit river, Chalt up the Hunza river, and the Parishing valley up the Astor river (Schaller and Khan, 1975). The occurrence of this markhor on the right side of the Yasin valley (Gilgit District) in the recent past (Schaller and Kahn, 1975) was also reported to R. Hess in 1986, but could not be confirmed. The flare-horned markhor is also found around Chitral and the border areas with Afghanistan where it inhabits a number of valleys along the Kunar river (Chitral District), from Arandu on the west bank and Drosh on the east bank, up to Shoghor along the Lutkho river, and as far as Barenis along the Mastuj river (Schaller and Khan, 1975).

Capra falconeri heptneri (Bukharan Markhor )

This subspecies previously occupied most of the mountains lying along the north banks of the Upper Amu Darya and the Pyanj rivers from Turkmenistan to Tajikistan. Today it is found in only about two to three scattered populations in a greatly reduced distribution. It is limited to the region between lower Pyanj and the Vakhsh rivers near Kulyab in Tajikistan (about 70”E and 37’40’ to 38”N), and in the Kugitangtau range in Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan (around 66’40’E and 37’30’N) (Weinberg et al.1997). This subspecies may possibly exist in the Darwaz peninsula of northern Afghanistan near the border with Tajikistan. Almost nothing was known of this subspecies or its distribution in Afghanistan before 1979 (Habibi, 1977), and no new information has been developed in Afghanistan since that time.

Capra falconeri megaceros ( Kabul Markhor )

In Afghanistan, at least until 1978, this markhor survived only in the Kabul Gorge and the Kohe Safi area of Kapissa, and in some isolated pockets in between. Intensive hunting pressure had forced it into the most inaccessible regions of its once wider range in the mountains of Kapissa and Kabul Provinces. In Pakistan, the most comprehensive study of the distribution and status of the straight-horned markhor comes from Schaller and Khan (1975). They showed a huge recent past range for this subspecies, but the present range in Pakistan consists only of small isolated areas in Baluchistan, a small area in NWFP, and one unconfirmed occurrence in Dera Ghazi Khan District (Punjab Province). Virk (1991) summarized the actual information for Baluchistan Province and confirmed the subspecies’ presence in the area of the Koh-i-Sulaiman (District Zhob) and the Takatu hills (District Quetta), both according to Ahmad (1989), and in the Torghar hills of the Toba Kakar range (District Zhob) (Tareen, 1990). The NWFP Forest Department (NWFP, 1987) considered that the areas of Mardan and Sheikh Buddin were still inhabited by the subspecies. There is no actual information about the Safed Koh range (Districts of Kurram and Khyber) where, according to Schaller and Khan (1975), probably at least 100 animals lived on the Pakistan side of the border at the time of their survey.

Population

The global population is estimated to be less than 2,500 mature individuals, although recent data are lacking for most parts of its range.

Capra falconeri falconeri

In Afghanistan, some 350 markhor were counted in western Nuristan (Petocz, 1972), which was considered a small proportion of the animals present. The population was believed to be declining steeply 10 years ago. Camera and hunter surveys conducted by the Wildlife Conservation Society in Nuristan during 2006-07 suggest that the species is now quite rare, and remaining individuals continue to be of interest to poachers.

In 1975, markhor were estimated to total 250 to 300 animals in India (Schaller and Khan, 1975). In 2005, Ranjitsinh et al. (2005) conducted surveys in most of the historical range of markhor in the Pir Panjal mountains of Jammu and Kashmir, observing 155 markhor within 2 of the 7 blocks surveyed. They guessed the total population within the surveyed area of Jammu and Kashmir to be some 280-330 markhor (although stressed that they did not believe this represented a true population increase from previous estimates). Bhatnagar et al. (2007) estimated 63 ±16 in the Limber catchment of this area.

In Pakistan, there are comparable population numbers over the last 20 years for three areas. 1) In 1970, the Chitral Gol, a valley of 77.5 km² in the Chitral District, and at that time the private hunting reserve of the Mehtar of Chitral, was estimated to harbor 100 to 125 animals (Schaller and Mirza, 1971). In 1984, this area was declared a National Park, and by 1985-86, it contained 160 (census) to 300 (estimated) animals. In addition, the proportion of males 24.5 years old increased during the same period (Hess, 1986). Within this time span, Aleem (1979) registered a maximum of 520 animals in Chitral Gol in 1979. The increase was attributed to better protection from poaching and to other improvement efforts in the Park (Malik, 1985). However, according to the latest official census (Ahmad, unpubl. data), the population in Chitral Gol NP was reduced to 195 markhor in 1987. 2) For the Tushi GR in the Chitral District, Schaller and Khan (1975) estimated 125 animals, a number similar to that estimated in 1985-86 (anonymous 1986, Hess in press). 3) The population of markhor in the Kargah GS (Gilgit District) was estimated by Roberts (1969) as not less than 500 to 600 animals; by Schaller and Khan (1975) as 50; by Rasool (no date, probably 1976) as 109; by Hess (1986) as 50 to 75; and by Rasool (unpubl. data) in 1991 as 40-50. In 1983, Rasool (unpubl. data) estimated that this area was the best area for markhor within the Gilgit District. Schaller and Khan (1975) estimated a total of at least 5,250 flare-horned markhor living in Pakistan, in the border areas with Afghanistan, and in India. The official census for Chitral District gave 6 17 markhor for 1985-86, and the NWFP Forest Department (NWFP, 1992) estimated 1,075 for the whole province (619 - Chitral, 109 - Dir, 58 - Swat, 221 - Kohistan, 50 - Mansehra; NWFP, 1992). The Wildlife Wing (Northern Areas Forest Dept., unpubl. data) estimated a total of 1,000 to 1,500 markhor in the Northern Areas in 1993 (Districts Gilgit, Diamir and Baltistan), though there may be no more than a maximum of 40 to 50 animals for a single area. Hence the population of this subspecies appears to have decreased since 1975. Today, less than 2,500 to 3,000 flare-horned markhor are estimated to survive in Pakistan.

Capra falconeri heptneri

In the ex-Soviet republics, the total population was estimated to be about 700 animals, and numbers generally decreasing in the 1990s (Shackleton et al. 1997), although Weinberg et al. (1997), based on reports from game wardens and local inhabitants, believed the population in Kugitang Nature Reserve in eastern Turkmenistan was increasing during the mid-1990s. In the Khozratisho range and in Kushvoristone (Tajikistan) there were around 350 markhor (Sokov, 1989), but nothing is known about current population numbers in Tajikistan. A recent survey in Kugitang revealed that its western (Turkmenistan) slopes harbor over 250 markhor (Weinberg et al. 1997, Fedosenko et al. 2000). In the early 1980s there were 400 in the whole of Uzbekistan according to the Uzbek Red Data Book (1983), but in 1994 there were only 290 estimated in this Republic, with only 86 counted in the Surkhan Nature Reserve in May 1993 (Chernagaev et al., 1995). There is no estimate for Afghanistan.

Capra falconeri megaceros

In Afghanistan, very few animals survived even 10 years ago, perhaps 50-80 in the Kohe Safi region, with a few in other isolated pockets. In Pakistan, Schaller and Khan (1975) estimated that more than 2,000 individuals remained throughout the entire range of straight-horned markhor. Roberts (1969) estimated that the total population of the former subspecies C. f. jerdoni, restricted mainly to the Province of Baluchistan, may have exceeded 1,000 animals, but that it was severely threatened because it survived in discontinuous and isolated pockets. For this same area, Schaller and Khan (1975) estimated less than 1,000 animals. Roberts (1969) believed that the main concentration of this former subspecies was in the Toba Kakar and Torghar hills and numbers could have been less than 500. Johnson (1997) estimated there were 695 Sulaiman markhor in the Torghar Hills in 1994. However, Rosser et al. (2005) summarized results from more recent surveys that suggested markhor in the Torghar Hills had increased to over 1,600 by the year 2000. Schaller and Khan (1975) estimated 150 straight-horned markhor living in the Takatu hills in 1971, but later Ahmad (1989) reported that only 50 still existed in these hills, and only 100 in the area of Koh-i-Sulaiman. The NWFP Forest Department (NWFP, 1992) gave a total of only 24 animals for the whole province: 12 for the Mardan area, and 12 for the Sheikh Buddin NP. There is no recent estimate for the total number of straight-horned markhor in Pakistan.

Threats

Capra falconeri falconeri

Within Afghanistan, markhor have been traditionally hunted in Nuristan and Laghman, and this may have intensified during the war. Domestic livestock were also increasing 10 years ago, creating competition for forage. According to surveys conducted by the Wildlife Conservation Society in Nuristan during 2007, markhor continue to be attractive for local hunters (despite a nominal ban on hunting nationwide). The continued existence of markhor in India is threatened by hunting and some habitat alteration. The small population of markhor in India justifies its Endangered status. The primary current threat related to hunting is increasing in association with the civil unrest and armed conflict present in the region of its habitat along India’s border with Pakistan. Thus, the main threat to markhor in India is their value as food within areas of armed conflict, although their high value as a trophy species also makes them sought after by hunters. Flare-horned markhor generally occur only in small (<100), scattered populations and at low densities throughout most of northern Pakistan. Control of poaching in Chitral Gol NP has been successful (Malik, 1985), and similar protection should be afforded other populations. Such actions alone may not be sufficient, however. Despite less poaching, markhor numbers have decreased and no more than 200 are believed to remain in Chitral Gol NP (Ahmad, unpubl. data).

Capra falconeri heptneri

In Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, markhor are reportedly poached for meat and for horns which are used for medicinal purposes in the large Asian market. Animals are also threatened by habitat loss, disturbance and forage competition from domestic livestock.

Capra falconeri megaceros

In Afghanistan, excessive hunting by local people and forage competition with livestock were pushing markhor to the periphery of its range. Such severe pressure was endangering the population towards a slow demise, and its status is unlikely to have improved since. In Pakistan, hunting and livestock competition, as well as significant habitat loss caused by logging in the Suleiman range, which is the most important area of straight-horned markhor’s distribution.

Conservation

Capra falconeri is listed in Appendix I of CITES.

Capra falconeri falconeri

Listed in Appendix I of CITES. Within Afghanistan, the species was protected nominally by a nationwide presidential decree banning hunting, but this ban was not generally enforced. In 2009 the species as a whole was listed on Afghanistan’s Protected Species List, making any hunting or trade of this species within the country illegal. Conservation measures proposed include: 1) census current population numbers, productivity and distributions; 2) re-assess conservation potentials after population surveys have been made; and, based on these data 3) consider a series of hunting reserves that have full support of the local people. This is probably the best chance for the flare-horned markhor’s survival. It will be critical to the success of such a program that the local people receive a substantial benefit from the operation of such reserves. Nuristan and Laghman are home to some of the toughest tribes in the country, with non-integrated societies that are frequently at odds with each other.

It is a fully protected (Schedule I) species in Jammu and Kashmir’s Wildlife (Protection) Act of 1978 (Ganhar, 1979). Currently, markhor in valley occurs in only three small protected areas: the Limber Game Reserve and the Lachipora and Hirapora Wildlife Sanctuaries. Conservation measures proposed include: 1) A new survey, with subsequent monitoring, is urgently needed to reassess the current status of the Astor markhor in India. However, this will have to await the easing of political tension and violence in the area. 2) Consider future re-introductions to previously inhabited ranges in the Pir Panjal mountains.

In Pakistan, the markhor is completely protected by federal law (Rao, 1986). A trophy hunting program for markhor was initiated in 1998, with a total of 7 animals legally taken through 2001 (Shackleton 2001). The quota was increased by CITES in 2002 from 6 to 12 animals due to the success of the program with the purpose of encouraging local communities for conservation of markhor through economic incentives from trophy hunting program. The central government issues permits only to areas in which a community-based trophy hunting program has been established; as of 2000, 80% of hunter fees were mandated to go to the community (although inter-community, as well as provincial-federal disputes over receipts and permitting have occurred). The program has continued through 2007 with trophy price for markhor increasing from US $18,000 to about US $57,000. According of official records, approximately US $830,000 has been distributed to communities within Northwest Frontier Province since 1998 from hunter remittances from the 17 markhor taken since 1998 (A. Khan, unpublished data, Northwest Frontier Province Wildlife Management, 2008).

Several protected areas contain flare-horned markhor: NWFP - Chitral District: Chitral Gol NP, Drosh Gol GR, Gahirat Gol GR, Goleem Gol GR, Goleen Gol GR, Purit Gol- Chinar Gol GR, Tushi GR (NWFP, 1992); Swat District: Totalai GR (Zool. Survey Dept., 1987). Northwn Areas - Gilgit District: Kargah WS, Naltar WS, Danyore GR, Sherqillah GR. (Rasool, no date); Diamir District: Astor WS, Tangir GR (Rasool, no date); Baltistan District: Baltistan WS, Askor Nallah GR (Rasool, no date). Azad Jammu and Kashmir - Muzaffarabad: Mauji CR, Qazi Nag GR, Hillan CR (Zool. Survey Dept., 1986); Poonch District: Phala GR (Qayyum, 1986, 47). Despite containing only about 200 animals, Chitral Gol NP may still protect the largest population of flare-horned markhor in the world—an indication of how critical the status of this subspecies is. Conservation measures proposed include: 1) stop allowing foreign hunters to take animals in Chitral Gol National Park; 2) treat Kargah GS as a focal area for markhor and enforce protection measures (Kargah is probably the best place for markhor in the Gilgit District, and like the Chitral Gol, should be rather easy to control because it is a traditional wildlife sanctuary and is close to Gilgit); 3) adopt a similar procedure for the area around Bagheecha in the Indus valley, which is one of the best places in Baltistan for markhor and also relatively easy to control; and 4) do not lift the hunting ban (which is excepted for approved community-based trophy hunts), as is currently being considered for the Northern Areas, because no single area contains greater than 50 animals.

Capra falconeri heptneri

Listed in Appendix I of CITES. It occurs in three Nature Reserves: Kugitang (Turkmensitan), Surkhan (Uzbekistan), and Dashti Jum (Tajikistan). Hunting by foreigners is currently permitted (at least two markhor/ year) in Tajikistan, with the government planning to allow more to be hunted in 1993-94, but the current status of hunting is uncertain. In Uzbekistan, two markhor were taken in 1994, and “Glavbiocontrol” of the State Committee for Nature Protection planned for two markhor licenses to be issued in 1995 (Anon., 1995b). A captive herd of markhor is reported in Dashti Jum NR, and a captive breeding program is apparently underway in Ramit Nature Reserve in the Gissar range (Tajikistan), with about 10 animals released by 1989. All markhor currently held in western zoos are considered to belong to this subspecies. Conservation measures proposed include: 1) stop poaching as soon as possible; 2) halt trophy hunting until professional biologists have completed adequate population surveys and thoroughly assessed the suitability of such programs; and 3) enlarge the size of the Kugitang Nature Reserve (Turkmenistan) on the western slopes of the Kugitangtau, because it protects only the high elevation summer habitat of markhor and the currently unprotected lower winter ranges are grazed by livestock. In Afghanistan, no measures were taken in the country and the species occurs in no protected areas. Much needed are surveys to determine if the taxon occurs in Afghanistan.

Capra falconeri megaceros

In Afghanistan, no measures were taken in the country and the species occurs in no protected areas. Status within country is Indeterminate (probably Endangered). Drastic measures will be required if the Kabul markhor is still alive today. It is necessary to carry out surveys to assess numbers and distribution as soon as possible. Public support for its conservation is essential if it is to survive, but this will be difficult to obtain.

Only one protected area is known to contain straight-horned markhor in Pakistan: Sheikh Buddin NP (previously a Wildlife Sanctuary) in Dera Ismail Khan District of NWFP (Zoological Survey Dept., 1987). The status of the subspecies in protected areas in Baluchistan is uncertain. Its occurrence is not confirmed in Chiltan-Hazarganji NP, and there is no reliable information for either Sasnamana or Ziarat Juniper WS’s. There are no reports of any in protected areas in Punjab. Due to recent protective measures in Koh-i-Sulaiman area, the population may be increasing slowly, but poaching still occurs in Takatu.

The Torghar Conservation Project in Baluchistan however, appears to have had success in reducing poaching and competition by livestock (Johnson 1997); the markhor population in this area is reported to have increased steadily since initiation of the program Torghar (Rosser et al. 2005).

Additional conservation measures proposed are: 1) immediately develop a conservation and management plan that includes information on the status and distribution of the subspecies in the areas it still inhabits; 2) include participatory management in the tribal areas in this plan; 3) besides the Torghar hills, consider the area of Koh-i-Sulaiman and the Takatu hills as a focal area for conservation efforts; and 4) if feasible, establish a captive population

Markhor is a species of wild goat inhabiting Northeast Afghanistan, Pakistan, Azad Kashmir and Indian-occupied Jammu & Kashmir, Southern Tajikistan and Southern Uzbekistan. It eats grasses and leaves. Females gestate for 135-170 days and give birth typically to 1-2 kids. Animals are sexually mature at 18-30 months, and live 12-13 years. Predators include the wolf, snow leopards, and lynx.

Markhor is the National Animal of Pakistan and listed as an Endangered Species. Some 2,500 mature individuals are left in the wild and population trend is on the decline.

Etymology

The colloquial name is thought by some to be derived from the Persian word mar, meaning snake, and khor, meaning "eater", which is sometimes interpreted to either represent the species' ability to kill snakes, or as a reference to its corkscrewing horns, which are somewhat reminiscent of coiling snakes. According to folklore (Explanation by Shah Zaman Gorgani), the markhor has the ability to kill a snake and eat it. Thereafter, while chewing the cud, a foam-like substance comes out of its mouth which drops on the ground and dries. This foam-like substance is sought after by the local people, who believe it is useful in extracting snake poison from snake bitten wounds.

Physical description

Markhor stand 65 to 115 centimetres (26 to 45 in) at the shoulder, 132 to 186 centimetres (52 to 73 in) in length and weigh from 32 to 110 kilograms (71 to 243 lb). They have the highest maximum shoulder height among the species in the genus Capra, but is surpassed in length and weight by the Siberian Ibex. The coat is of a grizzled, light brown to black colour, and is smooth and short in summer, while growing longer and thicker in winter. The fur of the lower legs is black and white. Markhor are sexually dimorphic, with males having longer hair on the chin, throat, chest and shanks. Females are redder in colour, with shorter hair, a short black beard, and are maneless. Both sexes have tightly curled, corkscrew-like horns, which close together at the head, but spread upwards toward the tips. The horns of males can grow up to 160 cm (64 inches) long, and up to 25 cm (10 inches) in females. The males have a pungent smell, which surpasses that of the domestic goat.

Behavior

Markhor are adapted to mountainous terrain, and can be found between 600 and 3,600 meters in elevation. They typically inhabit scrub forests made up primarily of oaks (Quercus ilex), pines (Pinus gerardiana), and junipers(Juniperus macropoda). They are diurnal, and are mainly active in the early morning and late afternoon. Their diets shift seasonally: in the spring and summer periods they graze, but turn to browsing in winter, sometimes standing on their hind legs to reach high branches. The mating season takes place in winter, during which the males fight each other by lunging, locking horns and attempting to push each other off balance. The gestation period lasts 135–170 days, and usually results in the birth of one or two kids, though rarely three. Markhor live in flocks, usually numbering nine animals, composed of adult females and their young. Adult males are largely solitary. Adult females and kids comprise most of the markhor population, with adult females making up 32% of the population and kids making up 31%. Adult males comprise 19%, while subadults (males aged 2–3 years) make up 12%, and yearlings (females aged 12–24 months) make up 9% of the population. Their alarm call closely resembles the bleating of domestic goats. Early in the season the males and females may be found together on the open grassy patches and clear slopes among the forest. During the summer, the males remain in the forest, while the females generally climb to the highest rocky ridges above

Geographic Range

This species is found in northeastern Afghanistan, southwest Jammu and Kashmir, northern and central Pakistan, southern Tajikistan and southern Uzbekistan (Grubb, 2005). It ranges in elevation from 600 to 3,600 m asl.

Capra falconeri falconeri ( Astor / Pir Panjal Markhor )

Within Afghanistan, it is historically been limited to the east in the high mountainous, monsoon forests of Laghman and Nuristan. Within India, markhor is restricted to part of the Pir Panjal range in southwestern Jammu and Kashmir (Ranjitsinh et al. 2005, Bhatnagar et al. 2007). Populations are scattered throughout this range starting from just east of the Banihal pass (50 km from the Chenab river) on the Jammu-Srinagar highway westward to the disputed border with Pakistan. Populations are known from recent surveys still to occur in catchments of the Limber and Lachipora rivers in the Jhelum Valley Forest Division, and around Shupiyan to the south of Srinagar. In Pakistan, Schaller and Khan (1975) considered the former Astor markhor (C. f. falconeri) and Kashmir markhor (C. f cashmiriensis) to be one subspecies – the flare-horned markhor. The distribution map given by Schaller and Khan (1975) seems still valid for this markhor, though the populations within the large range along the Indus have probably since decreased. Markhor is mainly confined to the Indus and its tributaries, as well as to the Kunar (Chitral) river and its tributaries. Along the Indus, it inhabits both banks from Jalkot (District Kohistan) upstream to near the Tungas village (District Baltistan), with Gakuch being its western limit up the Gilgit river, Chalt up the Hunza river, and the Parishing valley up the Astor river (Schaller and Khan, 1975). The occurrence of this markhor on the right side of the Yasin valley (Gilgit District) in the recent past (Schaller and Kahn, 1975) was also reported to R. Hess in 1986, but could not be confirmed. The flare-horned markhor is also found around Chitral and the border areas with Afghanistan where it inhabits a number of valleys along the Kunar river (Chitral District), from Arandu on the west bank and Drosh on the east bank, up to Shoghor along the Lutkho river, and as far as Barenis along the Mastuj river (Schaller and Khan, 1975).

Capra falconeri heptneri (Bukharan Markhor )

This subspecies previously occupied most of the mountains lying along the north banks of the Upper Amu Darya and the Pyanj rivers from Turkmenistan to Tajikistan. Today it is found in only about two to three scattered populations in a greatly reduced distribution. It is limited to the region between lower Pyanj and the Vakhsh rivers near Kulyab in Tajikistan (about 70”E and 37’40’ to 38”N), and in the Kugitangtau range in Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan (around 66’40’E and 37’30’N) (Weinberg et al.1997). This subspecies may possibly exist in the Darwaz peninsula of northern Afghanistan near the border with Tajikistan. Almost nothing was known of this subspecies or its distribution in Afghanistan before 1979 (Habibi, 1977), and no new information has been developed in Afghanistan since that time.

Capra falconeri megaceros ( Kabul Markhor )

In Afghanistan, at least until 1978, this markhor survived only in the Kabul Gorge and the Kohe Safi area of Kapissa, and in some isolated pockets in between. Intensive hunting pressure had forced it into the most inaccessible regions of its once wider range in the mountains of Kapissa and Kabul Provinces. In Pakistan, the most comprehensive study of the distribution and status of the straight-horned markhor comes from Schaller and Khan (1975). They showed a huge recent past range for this subspecies, but the present range in Pakistan consists only of small isolated areas in Baluchistan, a small area in NWFP, and one unconfirmed occurrence in Dera Ghazi Khan District (Punjab Province). Virk (1991) summarized the actual information for Baluchistan Province and confirmed the subspecies’ presence in the area of the Koh-i-Sulaiman (District Zhob) and the Takatu hills (District Quetta), both according to Ahmad (1989), and in the Torghar hills of the Toba Kakar range (District Zhob) (Tareen, 1990). The NWFP Forest Department (NWFP, 1987) considered that the areas of Mardan and Sheikh Buddin were still inhabited by the subspecies. There is no actual information about the Safed Koh range (Districts of Kurram and Khyber) where, according to Schaller and Khan (1975), probably at least 100 animals lived on the Pakistan side of the border at the time of their survey.

Population

The global population is estimated to be less than 2,500 mature individuals, although recent data are lacking for most parts of its range.

Capra falconeri falconeri

In Afghanistan, some 350 markhor were counted in western Nuristan (Petocz, 1972), which was considered a small proportion of the animals present. The population was believed to be declining steeply 10 years ago. Camera and hunter surveys conducted by the Wildlife Conservation Society in Nuristan during 2006-07 suggest that the species is now quite rare, and remaining individuals continue to be of interest to poachers.

In 1975, markhor were estimated to total 250 to 300 animals in India (Schaller and Khan, 1975). In 2005, Ranjitsinh et al. (2005) conducted surveys in most of the historical range of markhor in the Pir Panjal mountains of Jammu and Kashmir, observing 155 markhor within 2 of the 7 blocks surveyed. They guessed the total population within the surveyed area of Jammu and Kashmir to be some 280-330 markhor (although stressed that they did not believe this represented a true population increase from previous estimates). Bhatnagar et al. (2007) estimated 63 ±16 in the Limber catchment of this area.

In Pakistan, there are comparable population numbers over the last 20 years for three areas. 1) In 1970, the Chitral Gol, a valley of 77.5 km² in the Chitral District, and at that time the private hunting reserve of the Mehtar of Chitral, was estimated to harbor 100 to 125 animals (Schaller and Mirza, 1971). In 1984, this area was declared a National Park, and by 1985-86, it contained 160 (census) to 300 (estimated) animals. In addition, the proportion of males 24.5 years old increased during the same period (Hess, 1986). Within this time span, Aleem (1979) registered a maximum of 520 animals in Chitral Gol in 1979. The increase was attributed to better protection from poaching and to other improvement efforts in the Park (Malik, 1985). However, according to the latest official census (Ahmad, unpubl. data), the population in Chitral Gol NP was reduced to 195 markhor in 1987. 2) For the Tushi GR in the Chitral District, Schaller and Khan (1975) estimated 125 animals, a number similar to that estimated in 1985-86 (anonymous 1986, Hess in press). 3) The population of markhor in the Kargah GS (Gilgit District) was estimated by Roberts (1969) as not less than 500 to 600 animals; by Schaller and Khan (1975) as 50; by Rasool (no date, probably 1976) as 109; by Hess (1986) as 50 to 75; and by Rasool (unpubl. data) in 1991 as 40-50. In 1983, Rasool (unpubl. data) estimated that this area was the best area for markhor within the Gilgit District. Schaller and Khan (1975) estimated a total of at least 5,250 flare-horned markhor living in Pakistan, in the border areas with Afghanistan, and in India. The official census for Chitral District gave 6 17 markhor for 1985-86, and the NWFP Forest Department (NWFP, 1992) estimated 1,075 for the whole province (619 - Chitral, 109 - Dir, 58 - Swat, 221 - Kohistan, 50 - Mansehra; NWFP, 1992). The Wildlife Wing (Northern Areas Forest Dept., unpubl. data) estimated a total of 1,000 to 1,500 markhor in the Northern Areas in 1993 (Districts Gilgit, Diamir and Baltistan), though there may be no more than a maximum of 40 to 50 animals for a single area. Hence the population of this subspecies appears to have decreased since 1975. Today, less than 2,500 to 3,000 flare-horned markhor are estimated to survive in Pakistan.

Capra falconeri heptneri

In the ex-Soviet republics, the total population was estimated to be about 700 animals, and numbers generally decreasing in the 1990s (Shackleton et al. 1997), although Weinberg et al. (1997), based on reports from game wardens and local inhabitants, believed the population in Kugitang Nature Reserve in eastern Turkmenistan was increasing during the mid-1990s. In the Khozratisho range and in Kushvoristone (Tajikistan) there were around 350 markhor (Sokov, 1989), but nothing is known about current population numbers in Tajikistan. A recent survey in Kugitang revealed that its western (Turkmenistan) slopes harbor over 250 markhor (Weinberg et al. 1997, Fedosenko et al. 2000). In the early 1980s there were 400 in the whole of Uzbekistan according to the Uzbek Red Data Book (1983), but in 1994 there were only 290 estimated in this Republic, with only 86 counted in the Surkhan Nature Reserve in May 1993 (Chernagaev et al., 1995). There is no estimate for Afghanistan.

Capra falconeri megaceros

In Afghanistan, very few animals survived even 10 years ago, perhaps 50-80 in the Kohe Safi region, with a few in other isolated pockets. In Pakistan, Schaller and Khan (1975) estimated that more than 2,000 individuals remained throughout the entire range of straight-horned markhor. Roberts (1969) estimated that the total population of the former subspecies C. f. jerdoni, restricted mainly to the Province of Baluchistan, may have exceeded 1,000 animals, but that it was severely threatened because it survived in discontinuous and isolated pockets. For this same area, Schaller and Khan (1975) estimated less than 1,000 animals. Roberts (1969) believed that the main concentration of this former subspecies was in the Toba Kakar and Torghar hills and numbers could have been less than 500. Johnson (1997) estimated there were 695 Sulaiman markhor in the Torghar Hills in 1994. However, Rosser et al. (2005) summarized results from more recent surveys that suggested markhor in the Torghar Hills had increased to over 1,600 by the year 2000. Schaller and Khan (1975) estimated 150 straight-horned markhor living in the Takatu hills in 1971, but later Ahmad (1989) reported that only 50 still existed in these hills, and only 100 in the area of Koh-i-Sulaiman. The NWFP Forest Department (NWFP, 1992) gave a total of only 24 animals for the whole province: 12 for the Mardan area, and 12 for the Sheikh Buddin NP. There is no recent estimate for the total number of straight-horned markhor in Pakistan.

Threats

Capra falconeri falconeri

Within Afghanistan, markhor have been traditionally hunted in Nuristan and Laghman, and this may have intensified during the war. Domestic livestock were also increasing 10 years ago, creating competition for forage. According to surveys conducted by the Wildlife Conservation Society in Nuristan during 2007, markhor continue to be attractive for local hunters (despite a nominal ban on hunting nationwide). The continued existence of markhor in India is threatened by hunting and some habitat alteration. The small population of markhor in India justifies its Endangered status. The primary current threat related to hunting is increasing in association with the civil unrest and armed conflict present in the region of its habitat along India’s border with Pakistan. Thus, the main threat to markhor in India is their value as food within areas of armed conflict, although their high value as a trophy species also makes them sought after by hunters. Flare-horned markhor generally occur only in small (<100), scattered populations and at low densities throughout most of northern Pakistan. Control of poaching in Chitral Gol NP has been successful (Malik, 1985), and similar protection should be afforded other populations. Such actions alone may not be sufficient, however. Despite less poaching, markhor numbers have decreased and no more than 200 are believed to remain in Chitral Gol NP (Ahmad, unpubl. data).

Capra falconeri heptneri

In Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, markhor are reportedly poached for meat and for horns which are used for medicinal purposes in the large Asian market. Animals are also threatened by habitat loss, disturbance and forage competition from domestic livestock.

Capra falconeri megaceros

In Afghanistan, excessive hunting by local people and forage competition with livestock were pushing markhor to the periphery of its range. Such severe pressure was endangering the population towards a slow demise, and its status is unlikely to have improved since. In Pakistan, hunting and livestock competition, as well as significant habitat loss caused by logging in the Suleiman range, which is the most important area of straight-horned markhor’s distribution.

Conservation

Capra falconeri is listed in Appendix I of CITES.

Capra falconeri falconeri

Listed in Appendix I of CITES. Within Afghanistan, the species was protected nominally by a nationwide presidential decree banning hunting, but this ban was not generally enforced. In 2009 the species as a whole was listed on Afghanistan’s Protected Species List, making any hunting or trade of this species within the country illegal. Conservation measures proposed include: 1) census current population numbers, productivity and distributions; 2) re-assess conservation potentials after population surveys have been made; and, based on these data 3) consider a series of hunting reserves that have full support of the local people. This is probably the best chance for the flare-horned markhor’s survival. It will be critical to the success of such a program that the local people receive a substantial benefit from the operation of such reserves. Nuristan and Laghman are home to some of the toughest tribes in the country, with non-integrated societies that are frequently at odds with each other.

It is a fully protected (Schedule I) species in Jammu and Kashmir’s Wildlife (Protection) Act of 1978 (Ganhar, 1979). Currently, markhor in valley occurs in only three small protected areas: the Limber Game Reserve and the Lachipora and Hirapora Wildlife Sanctuaries. Conservation measures proposed include: 1) A new survey, with subsequent monitoring, is urgently needed to reassess the current status of the Astor markhor in India. However, this will have to await the easing of political tension and violence in the area. 2) Consider future re-introductions to previously inhabited ranges in the Pir Panjal mountains.

In Pakistan, the markhor is completely protected by federal law (Rao, 1986). A trophy hunting program for markhor was initiated in 1998, with a total of 7 animals legally taken through 2001 (Shackleton 2001). The quota was increased by CITES in 2002 from 6 to 12 animals due to the success of the program with the purpose of encouraging local communities for conservation of markhor through economic incentives from trophy hunting program. The central government issues permits only to areas in which a community-based trophy hunting program has been established; as of 2000, 80% of hunter fees were mandated to go to the community (although inter-community, as well as provincial-federal disputes over receipts and permitting have occurred). The program has continued through 2007 with trophy price for markhor increasing from US $18,000 to about US $57,000. According of official records, approximately US $830,000 has been distributed to communities within Northwest Frontier Province since 1998 from hunter remittances from the 17 markhor taken since 1998 (A. Khan, unpublished data, Northwest Frontier Province Wildlife Management, 2008).

Several protected areas contain flare-horned markhor: NWFP - Chitral District: Chitral Gol NP, Drosh Gol GR, Gahirat Gol GR, Goleem Gol GR, Goleen Gol GR, Purit Gol- Chinar Gol GR, Tushi GR (NWFP, 1992); Swat District: Totalai GR (Zool. Survey Dept., 1987). Northwn Areas - Gilgit District: Kargah WS, Naltar WS, Danyore GR, Sherqillah GR. (Rasool, no date); Diamir District: Astor WS, Tangir GR (Rasool, no date); Baltistan District: Baltistan WS, Askor Nallah GR (Rasool, no date). Azad Jammu and Kashmir - Muzaffarabad: Mauji CR, Qazi Nag GR, Hillan CR (Zool. Survey Dept., 1986); Poonch District: Phala GR (Qayyum, 1986, 47). Despite containing only about 200 animals, Chitral Gol NP may still protect the largest population of flare-horned markhor in the world—an indication of how critical the status of this subspecies is. Conservation measures proposed include: 1) stop allowing foreign hunters to take animals in Chitral Gol National Park; 2) treat Kargah GS as a focal area for markhor and enforce protection measures (Kargah is probably the best place for markhor in the Gilgit District, and like the Chitral Gol, should be rather easy to control because it is a traditional wildlife sanctuary and is close to Gilgit); 3) adopt a similar procedure for the area around Bagheecha in the Indus valley, which is one of the best places in Baltistan for markhor and also relatively easy to control; and 4) do not lift the hunting ban (which is excepted for approved community-based trophy hunts), as is currently being considered for the Northern Areas, because no single area contains greater than 50 animals.

Capra falconeri heptneri

Listed in Appendix I of CITES. It occurs in three Nature Reserves: Kugitang (Turkmensitan), Surkhan (Uzbekistan), and Dashti Jum (Tajikistan). Hunting by foreigners is currently permitted (at least two markhor/ year) in Tajikistan, with the government planning to allow more to be hunted in 1993-94, but the current status of hunting is uncertain. In Uzbekistan, two markhor were taken in 1994, and “Glavbiocontrol” of the State Committee for Nature Protection planned for two markhor licenses to be issued in 1995 (Anon., 1995b). A captive herd of markhor is reported in Dashti Jum NR, and a captive breeding program is apparently underway in Ramit Nature Reserve in the Gissar range (Tajikistan), with about 10 animals released by 1989. All markhor currently held in western zoos are considered to belong to this subspecies. Conservation measures proposed include: 1) stop poaching as soon as possible; 2) halt trophy hunting until professional biologists have completed adequate population surveys and thoroughly assessed the suitability of such programs; and 3) enlarge the size of the Kugitang Nature Reserve (Turkmenistan) on the western slopes of the Kugitangtau, because it protects only the high elevation summer habitat of markhor and the currently unprotected lower winter ranges are grazed by livestock. In Afghanistan, no measures were taken in the country and the species occurs in no protected areas. Much needed are surveys to determine if the taxon occurs in Afghanistan.

Capra falconeri megaceros

In Afghanistan, no measures were taken in the country and the species occurs in no protected areas. Status within country is Indeterminate (probably Endangered). Drastic measures will be required if the Kabul markhor is still alive today. It is necessary to carry out surveys to assess numbers and distribution as soon as possible. Public support for its conservation is essential if it is to survive, but this will be difficult to obtain.

Only one protected area is known to contain straight-horned markhor in Pakistan: Sheikh Buddin NP (previously a Wildlife Sanctuary) in Dera Ismail Khan District of NWFP (Zoological Survey Dept., 1987). The status of the subspecies in protected areas in Baluchistan is uncertain. Its occurrence is not confirmed in Chiltan-Hazarganji NP, and there is no reliable information for either Sasnamana or Ziarat Juniper WS’s. There are no reports of any in protected areas in Punjab. Due to recent protective measures in Koh-i-Sulaiman area, the population may be increasing slowly, but poaching still occurs in Takatu.

The Torghar Conservation Project in Baluchistan however, appears to have had success in reducing poaching and competition by livestock (Johnson 1997); the markhor population in this area is reported to have increased steadily since initiation of the program Torghar (Rosser et al. 2005).

Additional conservation measures proposed are: 1) immediately develop a conservation and management plan that includes information on the status and distribution of the subspecies in the areas it still inhabits; 2) include participatory management in the tribal areas in this plan; 3) besides the Torghar hills, consider the area of Koh-i-Sulaiman and the Takatu hills as a focal area for conservation efforts; and 4) if feasible, establish a captive population

Last edited: