Kompromat

ADMINISTRATOR

- Joined

- May 3, 2009

- Messages

- 40,366

- Reaction score

- 416

- Country

- Location

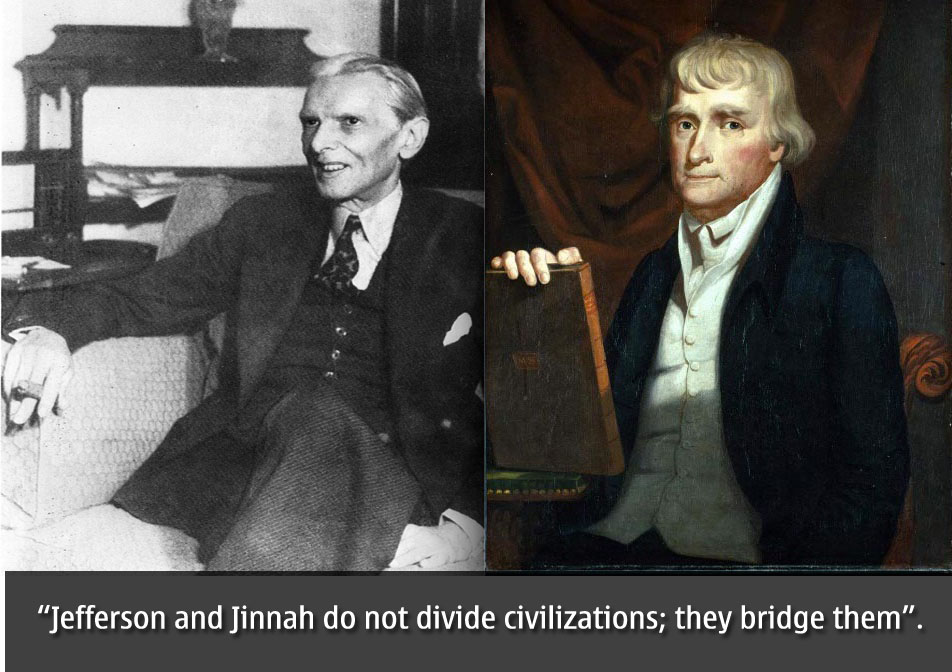

Thomas Jefferson and Mohammed Ali Jinnah: Dreams from two founding fathers

By Dr. Akbar Ahmed

Sunday, July 4, 2010

"You are free; you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any other place of worship. . . . We are starting in the days when there is no discrimination, no distinction between one community and another, no discrimination between one caste or creed and another. We are starting with this fundamental principle that we are all citizens and equal citizens of one state."

These are the words of a founding father -- but not one of the founders that America will be celebrating this Fourth of July weekend. They were uttered by Mohammed Ali Jinnah, founder of the state of Pakistan in 1947 and the Muslim world's answer to Thomas Jefferson.

When Americans think of famous leaders from the Muslim world, many picture only those figures who have become archetypes of evil (such as Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden) or corruption (such as Hamid Karzai and Pervez Musharraf). Meanwhile, many in the Muslim world remember American leaders such as George W. Bush and Dick Cheney, whom they regard as arrogant warriors against Islam, or Bill Clinton, whom they see as flawed and weak. Even President Obama, despite his rhetoric of outreach, has seen his standing plummet in Muslim nations over the past year.

Blinded by anger, ignorance or mistrust, people on both sides see only what they wish to see, what they expect to see.

Despite the continents, centuries and cultures separating them, Jefferson and Jinnah, the founding fathers of two nations born from revolution, can help break this impasse. In the years following Sept. 11, 2001, their worlds collided, but the things the two men share far outweigh that which divides them.

Each founding father, inspired by his own traditions but also drawing from the other's, concluded that society is best organized on principles of individual liberty, religious freedom and universal education. With their parallel lives, they offer a useful corrective to the misguided notion of a "clash of civilizations" between Islam and the West.

Jefferson is at the core of the American political ideal. As one biographer wrote, "If Jefferson was wrong, America is wrong. If America is right, Jefferson was right." Similarly, Jinnah is Pakistan. For most Pakistanis, he is "The Modern Moses," as one biography of him is titled.

The two were born subjects of the British Empire, yet both led successful revolts against the British and made indelible contributions to the identities of their young nations. Jefferson's drafting of the Declaration of Independence makes him the preeminent interpreter of the American vision; Jinnah's first speeches to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan in 1947, from which his statement on freedom of religion is drawn, are equally memorable and eloquent testimonies. As lawyers first and foremost, Jefferson and Jinnah revered the rule of law and the guarantee of key citizens' rights, embodied in the founding documents they shaped, reflecting the finest of human reason.

Particularly revealing is the overlap in the two men's intellectual influences. Jefferson's ideas flowed from the European Enlightenment, and he was inspired by Aristotle and Plato. But he also owned a copy of the Koran, with which he taught himself Arabic, and he hosted the first White House iftar, the meal that breaks the daily fast during the Muslim holy days of Ramadan.

And while Jinnah looked to the origins of Islam for political inspiration -- for him, Islam above all emphasized compassion, justice and tolerance -- he was steeped in European thought. He studied law in London, admired Prime Minister William Gladstone and Abraham Lincoln, and led the creation of Pakistan without advocating violence of any kind.

No one in public life is free of controversy, of course, not even a founding father. Both were involved in personal relationships that would later raise eyebrows (Jefferson with his slave mistress, Jinnah with a bride half his age). In political life, the two suffered accusations of inconsistency: Jefferson for not being robust in defending Virginia from an invading British fleet with Benedict Arnold in command; Jinnah for abandoning his role as ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity and becoming the champion of Pakistan.

The controversies did not end with their deaths. Jefferson's views on the separation of church and state generated animosity in his own time and as recently as this year, when the Texas Board of Education dropped him from a list of notable political thinkers. Meanwhile, hard-line Islamic groups have long condemned Jinnah as a kafir, or nonbeliever; "Jinnah Defies Allah" was the subtitle of an exposé in the December 1996 issue of the London magazine Khilafah, a publication of the Hizb ut-Tahrir, one of Britain's leading Muslim radical groups. (Jinnah's sin, according to the author, was his insistence that Islam stood for democracy and supported women's and minority rights.)

But today such opinions are marginal ones, and the founders' many contributions are commemorated with must-see national monuments -- the Jefferson Memorial in Washington, Jinnah's mausoleum in Karachi -- that affirm their standing as national heroes.

If anything, it is Jefferson and Jinnah who might be critical. If they could contemplate their respective nations today, they would share distress over the acceptance of torture and suspension of certain civil liberties in the former; and the collapse of law and order, resurgence of religious intolerance and widespread corruption in the latter. Their visions are more relevant than ever as a challenge and inspiration for their compatriots and admirers in both nations.

Jefferson and Jinnah do not divide civilizations; they bridge them.

akbar@american.edu

Dr. Akbar Ahmed is the Ibn Khaldun chair of Islamic studies at American University's School of International Service. This essay is adapted from his new book, "Journey Into America: The Challenge of Islam."

Thomas Jefferson and Mohammed Ali Jinnah: Dreams from two founding fathers

By Dr. Akbar Ahmed

Sunday, July 4, 2010

"You are free; you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any other place of worship. . . . We are starting in the days when there is no discrimination, no distinction between one community and another, no discrimination between one caste or creed and another. We are starting with this fundamental principle that we are all citizens and equal citizens of one state."

These are the words of a founding father -- but not one of the founders that America will be celebrating this Fourth of July weekend. They were uttered by Mohammed Ali Jinnah, founder of the state of Pakistan in 1947 and the Muslim world's answer to Thomas Jefferson.

When Americans think of famous leaders from the Muslim world, many picture only those figures who have become archetypes of evil (such as Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden) or corruption (such as Hamid Karzai and Pervez Musharraf). Meanwhile, many in the Muslim world remember American leaders such as George W. Bush and Dick Cheney, whom they regard as arrogant warriors against Islam, or Bill Clinton, whom they see as flawed and weak. Even President Obama, despite his rhetoric of outreach, has seen his standing plummet in Muslim nations over the past year.

Blinded by anger, ignorance or mistrust, people on both sides see only what they wish to see, what they expect to see.

Despite the continents, centuries and cultures separating them, Jefferson and Jinnah, the founding fathers of two nations born from revolution, can help break this impasse. In the years following Sept. 11, 2001, their worlds collided, but the things the two men share far outweigh that which divides them.

Each founding father, inspired by his own traditions but also drawing from the other's, concluded that society is best organized on principles of individual liberty, religious freedom and universal education. With their parallel lives, they offer a useful corrective to the misguided notion of a "clash of civilizations" between Islam and the West.

Jefferson is at the core of the American political ideal. As one biographer wrote, "If Jefferson was wrong, America is wrong. If America is right, Jefferson was right." Similarly, Jinnah is Pakistan. For most Pakistanis, he is "The Modern Moses," as one biography of him is titled.

The two were born subjects of the British Empire, yet both led successful revolts against the British and made indelible contributions to the identities of their young nations. Jefferson's drafting of the Declaration of Independence makes him the preeminent interpreter of the American vision; Jinnah's first speeches to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan in 1947, from which his statement on freedom of religion is drawn, are equally memorable and eloquent testimonies. As lawyers first and foremost, Jefferson and Jinnah revered the rule of law and the guarantee of key citizens' rights, embodied in the founding documents they shaped, reflecting the finest of human reason.

Particularly revealing is the overlap in the two men's intellectual influences. Jefferson's ideas flowed from the European Enlightenment, and he was inspired by Aristotle and Plato. But he also owned a copy of the Koran, with which he taught himself Arabic, and he hosted the first White House iftar, the meal that breaks the daily fast during the Muslim holy days of Ramadan.

And while Jinnah looked to the origins of Islam for political inspiration -- for him, Islam above all emphasized compassion, justice and tolerance -- he was steeped in European thought. He studied law in London, admired Prime Minister William Gladstone and Abraham Lincoln, and led the creation of Pakistan without advocating violence of any kind.

No one in public life is free of controversy, of course, not even a founding father. Both were involved in personal relationships that would later raise eyebrows (Jefferson with his slave mistress, Jinnah with a bride half his age). In political life, the two suffered accusations of inconsistency: Jefferson for not being robust in defending Virginia from an invading British fleet with Benedict Arnold in command; Jinnah for abandoning his role as ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity and becoming the champion of Pakistan.

The controversies did not end with their deaths. Jefferson's views on the separation of church and state generated animosity in his own time and as recently as this year, when the Texas Board of Education dropped him from a list of notable political thinkers. Meanwhile, hard-line Islamic groups have long condemned Jinnah as a kafir, or nonbeliever; "Jinnah Defies Allah" was the subtitle of an exposé in the December 1996 issue of the London magazine Khilafah, a publication of the Hizb ut-Tahrir, one of Britain's leading Muslim radical groups. (Jinnah's sin, according to the author, was his insistence that Islam stood for democracy and supported women's and minority rights.)

But today such opinions are marginal ones, and the founders' many contributions are commemorated with must-see national monuments -- the Jefferson Memorial in Washington, Jinnah's mausoleum in Karachi -- that affirm their standing as national heroes.

If anything, it is Jefferson and Jinnah who might be critical. If they could contemplate their respective nations today, they would share distress over the acceptance of torture and suspension of certain civil liberties in the former; and the collapse of law and order, resurgence of religious intolerance and widespread corruption in the latter. Their visions are more relevant than ever as a challenge and inspiration for their compatriots and admirers in both nations.

Jefferson and Jinnah do not divide civilizations; they bridge them.

akbar@american.edu

Dr. Akbar Ahmed is the Ibn Khaldun chair of Islamic studies at American University's School of International Service. This essay is adapted from his new book, "Journey Into America: The Challenge of Islam."

Thomas Jefferson and Mohammed Ali Jinnah: Dreams from two founding fathers