Pakistan’s nuclear forces, 2011

1. Hans M. Kristensen

2. Robert S. Norris

Next Section

Abstract

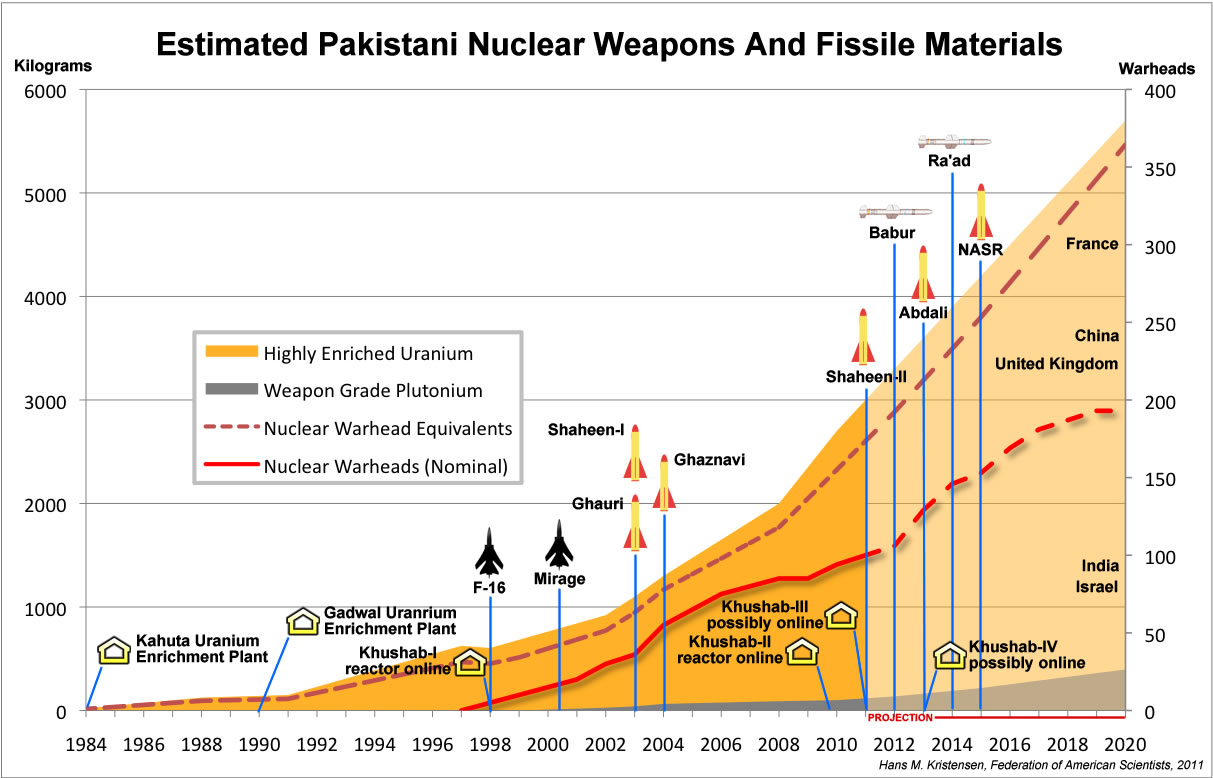

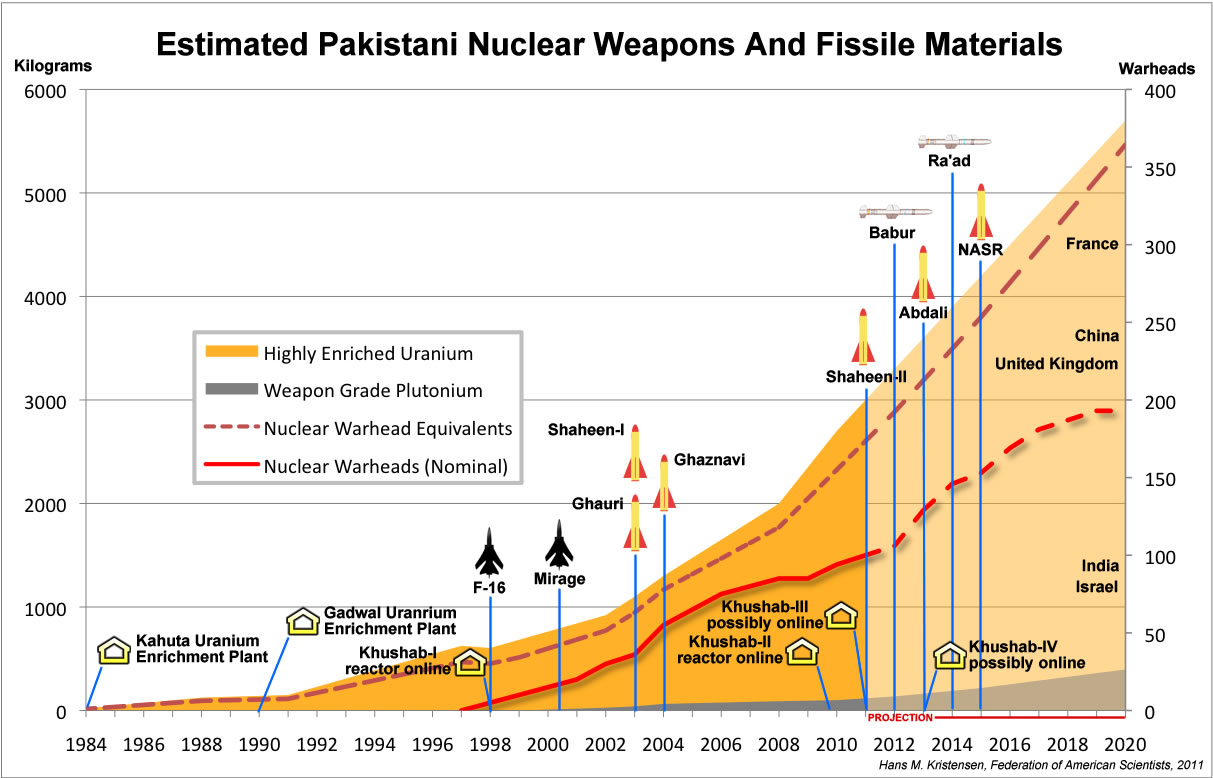

The US raid that killed Osama bin Laden has raised concerns about the security of Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal. In the process of building two new plutonium production reactors and a new reprocessing facility to fabricate more nuclear weapons fuel, Pakistan is also developing new delivery systems. The authors estimate that if the country’s expansion continues, Pakistan’s nuclear weapons stockpile could reach 150–200 warheads in a decade. They assess the country’s nuclear forces, providing clear analysis of its nuclear command and control, nuclear-capable aircraft, ballistic missiles, and cruise missiles.

Despite its political instability, Pakistan continues to steadily expand its nuclear capabilities and competencies; in fact, it has the world’s fastest-growing nuclear stockpile. In the aftermath of the US raid that killed Osama bin Laden, who had made his hideout in an Islamabad suburb, concerns about the security of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons are likely to keep pace with the growth of Pakistan’s arsenal. Pakistan is building two new plutonium production reactors and a new reprocessing facility with which it will be able to fabricate more nuclear weapons fuel. It is also developing new delivery systems. Enhancements to Pakistan’s nuclear forces include a new nuclear-capable medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM), the development of two new nuclear-capable short-range ballistic missiles, and the development of two new nuclear-capable cruise missiles.

We estimate that Pakistan has a nuclear weapons stockpile of 90–110 nuclear warheads, an increase from the estimated 70–90 warheads in 2009 (Norris and Kristensen, 2009). The US Defense Intelligence Agency projected in 1999 that by 2020 Pakistan would have 60–80 warheads (Defense Intelligence Agency, 1999); Pakistan appears to have reached that level in 2006 or 2007 (Norris and Kristensen, 2007), more than a decade ahead of predictions. In January 2011, our estimate (DeYoung, 2011) of Pakistan’s stockpile was confirmed in the New York Times by “officials and outsiders familiar with the American assessment,” who said that the official US estimate for “deployed weapons” ranged from the mid-90s to more than 110 (Sanger and Schmitt, 2011).1 With four new delivery systems and two plutonium production reactors under development, however, the rate of Pakistan’s stockpile growth may even increase over the next 10 years.

The Pakistani government has not defined the number and type of nuclear weapons that its minimum deterrent requires. But Pakistan’s pace of nuclear modernization—and its development of several short-range delivery systems—indicates that its nuclear posture has entered an important new phase and that a public explanation is overdue.

Fissile material and warhead production

As of late 2010, the International Panel on Fissile Materials estimated that Pakistan had an inventory of approximately 2,600 kilograms (kg) of highly enriched uranium (HEU) and roughly 100 kg of weapon-grade plutonium (International Panel on Fissile Materials, 2010). This is enough to produce 160–240 warheads, assuming that each warhead’s solid core uses either 12–18 kg of HEU or 4–6 kg of plutonium.2

Reliable warhead estimates are difficult to arrive at but generally are based upon several kinds of information, including: the amount of weapon-grade fissile material produced, warhead design proficiency, production rates, operational nuclear-capable delivery vehicle numbers, and government officials’ statements. Estimates must take into account that not all of a country’s fissile material ends up in warheads. Like other nuclear weapon states, Pakistan probably maintains a reserve of fissile material. Pakistan also lacks enough delivery vehicles to accommodate 160–240 warheads; furthermore, most delivery systems are dual-capable, with a portion of them presumably assigned non-nuclear missions. Finally, official statements often refer to “warheads” and “weapons” interchangeably, without making it clear whether it is the number of delivery vehicles or the warheads assigned to them that is being discussed.

How much plutonium or uranium is needed for a Pakistani nuclear warhead depends upon many variables, but three are particularly important: the technical capabilities of the scientists and engineers, the warhead design, and the desired yield (see Table 2). Skilled technicians need less fissile material to achieve a given yield. Though we do not know the skill level at which the Pakistani bomb designers are working, they have been at it since the 1970s, have had help from China, and have conducted several nuclear tests; these factors suggest that low- to medium-level technical skills are plausible.

Precise details about Pakistan’s nuclear warheads are not publicly known, but its initial warhead design was most likely an HEU fission implosion configuration. There is general consensus that China provided Pakistani nuclear scientist A. Q. Khan with the blueprints to the uranium implosion device that China detonated on October 27, 1966 (the so-called CHIC-4 test/design). It is also generally accepted that on May 26, 1990, China tested a Pakistani derivative of the CHIC-4 at its Lop Nor test site, with a yield in the 10–12 kiloton (kt) range.3 That range accords with estimates of Pakistan’s 1998 nuclear tests, which had yields somewhere between 5 and 12 kt. Refinements in boosting and plutonium use are the normal next steps in weapon improvements, along with miniaturization of the warheads to fit into smaller delivery vehicles. Pakistan is probably undertaking all of these improvements to arm its cruise and ballistic missiles, or both, with smaller payloads.

Pakistan may be producing 120–180 kg of HEU per year, an amount sufficient for 7–15 warheads. The uranium ore is mined at several locations throughout Pakistan, with more mines scheduled to open in the future. Uranium is extracted from the ore and processed into uranium hexafluoride and uranium metal at the Dera Ghazi Khan uranium processing facility in southern Punjab. Enrichment takes place at the Kahuta and Gadwal plants southeast and northwest of Islamabad, respectively (International Panel on Fissile Materials, 2010; Landay, 2009; US Department of Commerce, 1998).

For several years, Pakistan has operated a 40–50 megawatt thermal plutonium production reactor, Khushab-I, near Joharabad, and a second reactor, Khushab-II, at the same site is also believed to be operational (Albright and Brannan, 2011a). Each of these plutonium production reactors is capable of producing an estimated 6–12 kg of weapon-grade plutonium per year (depending on operating efficiency), for a combined total of 12–24 kg annually—enough for three to six nuclear weapons, assuming low-to-medium skill levels (4–6 kg per weapon) and a yield of 10 kt. At these rates, Pakistan may be producing enough HEU and weapon-grade plutonium for 10–21 warheads per year. Construction of the new Khushab-III and -IV plutonium production reactors is underway at the same site, though the fourth reactor is likely years away from completion (Albright and Brannan, 2011b). Once operational, these reactors could double Pakistan’s annual plutonium output, increasing the number of warheads it could build.

To handle its expanded plutonium production, Pakistan is augmenting its reprocessing capacity by building a second chemical separation facility at the Pakistan Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology, near Rawalpindi.4 The majority of weapons in Pakistan’s current nuclear arsenal are HEU-based, but the types of facilities it is building suggest that Pakistan wants to supplement (and perhaps eventually replace) its heavier HEU weapons with smaller, lighter plutonium-based designs that more easily fit on ballistic and cruise missiles.

If today’s rate of expansion continues, we estimate that over the next 10 years Pakistan’s nuclear weapons stockpile could potentially reach 150–200 warheads—a number comparable to the future British nuclear stockpile.

Previous SectionNext Section

Nuclear command and control

The revelation that Osama bin Laden had hidden for years in Abbottabad, Pakistan, only 53 kilometers (km) northeast of Islamabad—and only 16 km from a large military weapons depot with underground facilities—raised new questions about the security and control of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons. Outside Pakistan, observers wondered if the nuclear arsenal was secure from potential terrorist theft; inside Pakistan, observers wondered whether the arsenal was safe from a possible US or Indian incursion.

Exactly how Pakistan safeguards its nuclear weapons, and what type of “use-control” features its weapons have, is unclear. The weapons are thought to have some basic use-control features to prevent unauthorized use. Its facilities and weapons are said to be “widely dispersed in the country” (Sanger, 2009), with most of the arsenal located south of Islamabad (Kralev and Slavin, 2009). Furthermore, the weapons are thought to be stored unassembled, with the cores separate from the weapons and the weapons stored away from the delivery vehicles (at least under normal circumstances).5

Adm. Michael Mullen, US Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said in 2009 that he believes Pakistan has “actually put in an increased level of security measures in the last three or four years” to protect its nuclear arsenal (Mullen, 2009). In 2010, he said, “These are the most important weapons in the Pakistani arsenal. That is understood by the leadership, and they go to extraordinary efforts to protect and secure them. These are their crown jewels” (Ahmed, 2010). James Miller, the principal deputy undersecretary of defense for policy, says that the United States has “offered any assistance that Pakistan might desire with respect to [the] means for security of nuclear weapons” (Grossman, 2011). In past years, Pakistan has accepted tens of millions of dollars of US aid under a classified program to improve its nuclear security (Sanger and Broad, 2007), but whether that aid has continued is unclear. Pervez Musharraf, former president of Pakistan, recently claimed that the United States plays a “zero role” in helping to secure the Pakistani arsenal (Bast, 2011).

For Pakistan, however, the successful US raid against bin Laden deep inside Pakistan has probably reinforced concerns that its nuclear weapons might be vulnerable to US strikes or capture. Pakistan defended the general security of its arsenal, stating, “As regards the possibility of similar hostile action against our strategic assets, the [Pakistani military] reaffirmed that, unlike an undefended civilian compound, our strategic assets are well protected and an elaborate defensive mechanism is in place” (ISPR, 2011e).

Nuclear-capable aircraft

Pakistan probably assigns its F-16A/B aircraft to the nuclear role, although some Mirage Vs could also have a nuclear mission. The F-16A/Bs were supplied by the United States between 1983 and 1987, and the units with the nuclear mission probably include Squadrons 9 and 11 at Sargodha Air Base, which is located 160 km (100 miles) northwest of Lahore. Pakistan’s F-16A/Bs, which have a range of 1,600 km (extendable when equipped with drop tanks), most likely carry a single bomb on the centerline pylon. The absence of extra security features at Sargodha suggests that nuclear weapons are not stored at the base; instead, bombs assigned to the aircraft may be kept at the Sargodha Weapons Storage Complex, 10 km south of the base, or at operational or satellite bases west and south of Sargodha, such as near Quetta and Karachi, where the F-16A/Bs would pick up their bombs if necessary.

Acquisition of additional F-16s was prevented for a time by the Pressler Amendment, which prohibited US military aid to suspected nuclear weapon states. After September 2001, however, the restrictions were loosened, and Pakistan requested a total of 36 F-16C/Ds from the Pentagon, as well as 60 upgrade kits to extend the life of its existing F-16A/Bs. The first 18 new F-16C/D Block 52 aircraft were integrated into the No. 5 Squadron at Shahbaz Air Base in Jacobabad in March 2011, replacing aging French-manufactured Mirage Vs (Hardy, 2011). In preparation for the delivery of the F-16C/D aircraft, Pakistani pilots spent seven months training at Luke Air Force Base in Arizona (Combat Aircraft, 2010).

Ballistic missiles

Pakistan has three operational nuclear-capable ballistic missiles: the short-range Ghaznavi (Hatf-3) and Shaheen-1 (Hatf-4) and the medium-range Ghauri (Hatf-5). It has at least three other nuclear-capable ballistic missiles under development: the medium-range Shaheen-2 (Hatf-6), which may soon be operational, and the short-range Abdali (Haft-2) and Nasr (Haft-9) systems.

The successful April 2011 test-launch of the Nasr, which Pakistan refers to as a short-range, surface-to-surface, multi-tube ballistic missile, is the country’s most significant recent missile development. With a range of only 60 km and apparently intended to target troop formations rather than cities, the Nasr appears to fall into the category of nonstrategic or tactical nuclear weapons, rather than weapons intended for strategic deterrence. According to Pakistan’s military news organization, Inter Services Public Relations (ISPR), the Nasr “carries nuclear warheads [sic] of appropriate yield with high accuracy, shoot and scoot attributes” and was developed as a “quick response system” to “add deterrence value” to Pakistan’s strategic weapons development program “at shorter ranges” in order “to deter evolving threats” (ISPR, 2011c), a possible reference to India’s large conventional ground forces and so-called Cold Start doctrine.6 The missile launcher used with the Nasr appears similar to the one used by the Chinese DF-10 ground-launched cruise missile or A-100 multiple rocket launcher.

The Nasr test followed the successful March test-launch of the 180-km-range Abdali dual-capable ballistic missile. Using language similar to its description of the Nasr, the Pakistani government stated that the Abdali “provides Pakistan with an operational level capability, additional to the strategic level capability” (ISPR, 2011b), another indication that Pakistan’s nuclear doctrine is developing a new nonstrategic role for short-range missiles. The Abdali is a mysterious program because its designation, Hatf-2, suggests that its origins date back to before the 2004 introduction of the Ghaznavi (Hatf-3), indicating that its development was somehow delayed.

The solid-fueled, single-stage Ghaznavi is believed to be derived from the Chinese M-11 missile, of which Pakistan acquired approximately 30 in the early 1990s. A classified US National Intelligence Estimate on China’s missile-related assistance to Pakistan concluded in 1996—two years before Pakistan’s nuclear tests—that Pakistan probably had developed nuclear warheads for the missiles (Smith, 1996). Pakistan test-launched a Ghaznavi on May 8, 2010, as part of an annual field training exercise of the Army Strategic Force Command to test “the operational readiness of Strategic Missile Groups” that are equipped with the missile system (ISPR, 2010).

On the same day, as part of the same exercise, Pakistan also test-launched a Shaheen-1, which is a reverse-engineered Chinese M-9 missile. The Shaheen-1 has been in service since 2003 and has a range greater than 450 km. The 2,000-km range Shaheen-2 is a two-stage MRBM that has been under development for more than a decade and is thought to be nearing operational capability, if it hasn’t happened already. The Shaheen-2 may replace the Ghauri MRBM, Pakistan’s only liquid-fueled nuclear-capable ballistic missile.7

Cruise missiles

Pakistan is developing two new cruise missiles, the Babur (Hatf-7) and Ra’ad (Hatf-8), and it uses similar language to describe both missiles. According to the ISPR, the Babur and Ra’ad both have “stealth capabilities” and “pinpoint accuracy,” and each is described as “a low-altitude, terrain-hugging missile with high maneuverability” (ISPR 2011a, 2011d).

The ground-launched Babur has been test-launched seven times, most recently on February 10, 2011; has a range of 600 km; and can “carry strategic and conventional warheads” (ISPR, 2011a). The Babur looks similar to the US Tomahawk sea-launched cruise missile, the Chinese DH-10 ground-launched cruise missile, and the Russian air-launched AS-15. The Babur also appears much slimmer than Pakistan’s ballistic missiles, suggesting that Pakistan has had success with warhead miniaturization.

On April 29, 2011, Pakistan successfully test-launched a Ra’ad (“thunder”

missile for the third time. The Pakistani government issued a statement that the Ra’ad is an air-launched cruise missile (ALCM) that “can deliver nuclear and conventional warheads” to a range greater than 350 km. “This missile system has enabled Pakistan to achieve a greater strategic stand-off capability on land and at sea,” according to the ISPR (2011d). The Ra’ad was first test-launched on August 25, 2007, by a Mirage aircraft, and it is possible that in the future Pakistan’s air force will deploy Ra’ad ALCMs on Mirage V or F-16 squadrons

missile for the third time. The Pakistani government issued a statement that the Ra’ad is an air-launched cruise missile (ALCM) that “can deliver nuclear and conventional warheads” to a range greater than 350 km. “This missile system has enabled Pakistan to achieve a greater strategic stand-off capability on land and at sea,” according to the ISPR (2011d). The Ra’ad was first test-launched on August 25, 2007, by a Mirage aircraft, and it is possible that in the future Pakistan’s air force will deploy Ra’ad ALCMs on Mirage V or F-16 squadrons

missile for the third time. The Pakistani government issued a statement that the Ra’ad is an air-launched cruise missile (ALCM) that “can deliver nuclear and conventional warheads” to a range greater than 350 km. “This missile system has enabled Pakistan to achieve a greater strategic stand-off capability on land and at sea,” according to the ISPR (2011d). The Ra’ad was first test-launched on August 25, 2007, by a Mirage aircraft, and it is possible that in the future Pakistan’s air force will deploy Ra’ad ALCMs on Mirage V or F-16 squadrons