TOKYO— Ryoma Matsubayashi says he is still stung by a memory of a politician handing out campaign fliers who declined to give him one.

“He clearly wasn’t interested in young students who couldn’t vote,” said the 17-year-old Tokyo high-school student, who was prompted by the politician’s cold shoulder to eventually join a group advocating for the voting age to be lowered from 20.

That goal now looks within reach. In the coming days, Japan’s parliament will consider a bill—endorsed across party lines and widely expected to pass—to give 18-year-olds the right to vote.

ENLARGE

ENLARGE

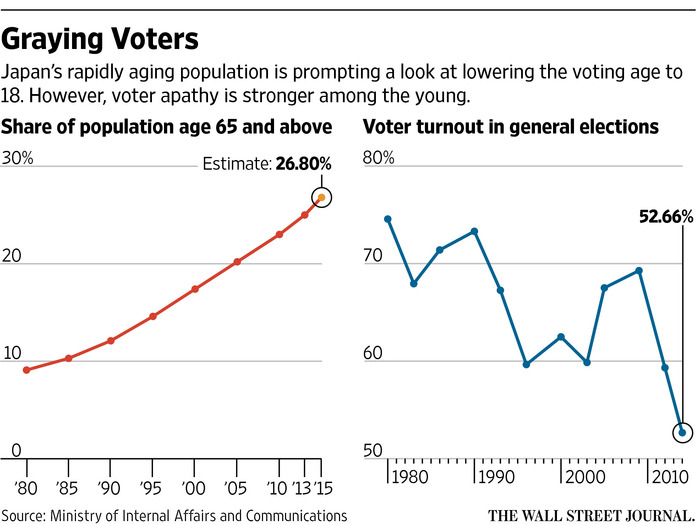

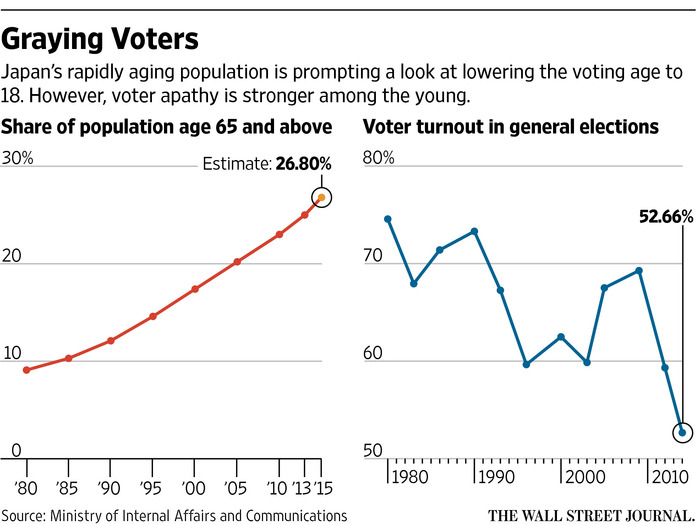

By itself, the move would add about 2%, or 2.4 million potential voters, to an electorate of 104 million. But it is a first stab at remedying a perception that the world’s fastest-aging nation has left the country’s young on the political sidelines.

A quarter of Japanese are older than 65—from just a 10th in 1985. That has created a political landscape where lawmakers court older voters with, for example, pledges to maintain generous pension payments. Often relegated to the back burner are issues important to future generations, such as job security and the salaries of temporary workers.

The demographic shift weighs heavily on Japan’s public finances, with social-security costs, including medical and nursing care, rising as the number of elderly grows. Meanwhile, Japan devotes just 2.9% of its economic output to education, among the lowest of the 34 member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. “Generational inequalities are expanding, due in part to policies excessively reflecting the voice of the older population,” said Ryohei Takahashi, who teaches at Chuo University in Tokyo and runs a nonprofit group promoting youth participation in politics.

ENLARGE

ENLARGE

Costs for medical and nursing care are rising in Japan as the number of elderly grows. Photo: Reuters

Japan is late to the game. Nearly 90% of countries allow 18-year-olds to vote. Exceptions include Saudi Arabia, Gabon and Malaysia. In a handful of countries including Brazil and Austria, the legal voting age is 16. The U.S. lowered the voting age to 18 from 21 in 1971, adding 11 million new voters, of which around 5.3 million exercised their right to vote in the 1972 election.

Japan’s planned revision would be the first since 1945, when the voting age was lowered to 20 from 25 and women were given the right to vote.

ENLARGE

ENLARGE

Women celebrate ‘Coming of Age Day’ for 20-year-olds in Tokyo. Photo: TK

That it comes now reflects both a population that has peaked and an economy that Prime Minister Shinzo Abe ’s revival program has so far failed to decisively lift out of decades of debilitating deflation. The combination, says Mr. Takahashi, has required the nation to reach out to the younger generation.

Polls have showed that younger voters place a premium on economic issues and have more faith that Abenomics will lift wages than older voters, a fact not lost on Mr. Abe and his allies. “I think the younger generation harbors a vague sense of insecurity toward their future,” said Hiromasa Nakano, a lawmaker from Komeito, a junior partner in Mr. Abe’s ruling coalition.

A survey taken by Nippon Life Insurance Co. last year showed that 17% of those under 30 believed they wouldn’t receive any pension payments under Japan’s current pension plan, compared with less than 1% among those in their 60s.

Mr. Abe may also be betting that the younger generation is more open to his efforts to lift restrictions on Japan’s military by changing the country’s pacifist constitution, in place since the end of World War II. “Obviously the LDP thinks that constitutional revision could come down to votes on the margin and is betting that younger voters are less attached to the constitution than older voters,” said Tobias Harris, a Japan analyst at Teneo Intelligence.

‘I think the younger generation harbors a vague sense of insecurity toward their future.’

—Hiromasa Nakano, lawmaker

The young are in general less worked up about issues related to Japan’s wartime past, or its territorial disputes. Japan’s relationship with China and South Korea has worsened since Mr. Abe took power, but a government survey in October showed that those in their 20s harbored warmer feelings than people over 60 for Beijing and Seoul.

Yui Kobayashi, an 18-year-old high-school student, said she believed Japan, China and South Korea need to cooperate to find a peaceful resolution to the territorial issues, and said she was against Mr. Abe’s move to expand the role of the military. “I feel very scared when I imagine a future where me, my family and my friends may have to go to war,” said Ms. Kobayashi, who is active in the same youth group as Mr. Matsubayashi, Teen’s Rights Movement.

A poll taken by Kyodo News in August showed nearly 70% of those in their 20s and 30s opposed Mr. Abe’s plan to allow Japan to engage in collective self-defense, or coming to the aid of an ally under attack. But the poll indicated economic issues were a much higher priority for all age groups. Only 13% of those in their 20s and 30s expressed an interest in security policies.

A younger electorate could affect a number of social issues. Another Kyodo poll in September showed that those in their 20s were most supportive of promoting more women to senior positions. And according to a recent poll by the Asahi Shimbun newspaper, 60% to 70% of those in their 20s to 40s approve of moves to recognize same-sex marriages, compared with about a fifth of those 70 and older.

It isn’t clear how many newly eligible voters will actually cast a vote. A drop in voter turnout in Japan in recent years is especially pronounced among the young: Only 38% of voters in their 20s went to the polls in the 2012 general election, compared with 75% among those in their 60s.

ENLARGE

ENLARGE

Yui Kobayashi, right, asked young Japanese to vote in a mock election. Photo: Teen’s Rights Movement

And the broader demographic trend means the lower voting age will ultimately have limited impact. “A marginal increase in younger voters will do little to offset the power of retirees,” said Mr. Harris of Teneo Intelligence.

Sawa Isogai, a 19-year-old university student and a member of Ivote, a student organization promoting voter turnout, says that the change needs to be accompanied by better education.

“Teachers don’t discuss elections or the importance of voting at school; there’s a general lack of interest in politics among students,” she said.

Mr. Abe said Feb. 17 in parliament that the government would “take every opportunity” to promote awareness through cooperation with schools, election boards and local communities.

The bill is expected to take effect for upper-house elections in the summer of 2016—by which time Mr. Matsubayashi, who was snubbed by the politician with fliers, will have turned 18.

He now tries to steer conversations with classmates toward social issues and away from smartphone games.

“Everyone holds some kind of opinion on politics. It’s important to pull that out,” he said.

Japan’s Youth Stand to Gain Stronger Voice - WSJ

“He clearly wasn’t interested in young students who couldn’t vote,” said the 17-year-old Tokyo high-school student, who was prompted by the politician’s cold shoulder to eventually join a group advocating for the voting age to be lowered from 20.

That goal now looks within reach. In the coming days, Japan’s parliament will consider a bill—endorsed across party lines and widely expected to pass—to give 18-year-olds the right to vote.

By itself, the move would add about 2%, or 2.4 million potential voters, to an electorate of 104 million. But it is a first stab at remedying a perception that the world’s fastest-aging nation has left the country’s young on the political sidelines.

A quarter of Japanese are older than 65—from just a 10th in 1985. That has created a political landscape where lawmakers court older voters with, for example, pledges to maintain generous pension payments. Often relegated to the back burner are issues important to future generations, such as job security and the salaries of temporary workers.

The demographic shift weighs heavily on Japan’s public finances, with social-security costs, including medical and nursing care, rising as the number of elderly grows. Meanwhile, Japan devotes just 2.9% of its economic output to education, among the lowest of the 34 member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. “Generational inequalities are expanding, due in part to policies excessively reflecting the voice of the older population,” said Ryohei Takahashi, who teaches at Chuo University in Tokyo and runs a nonprofit group promoting youth participation in politics.

Costs for medical and nursing care are rising in Japan as the number of elderly grows. Photo: Reuters

Japan is late to the game. Nearly 90% of countries allow 18-year-olds to vote. Exceptions include Saudi Arabia, Gabon and Malaysia. In a handful of countries including Brazil and Austria, the legal voting age is 16. The U.S. lowered the voting age to 18 from 21 in 1971, adding 11 million new voters, of which around 5.3 million exercised their right to vote in the 1972 election.

Japan’s planned revision would be the first since 1945, when the voting age was lowered to 20 from 25 and women were given the right to vote.

Women celebrate ‘Coming of Age Day’ for 20-year-olds in Tokyo. Photo: TK

That it comes now reflects both a population that has peaked and an economy that Prime Minister Shinzo Abe ’s revival program has so far failed to decisively lift out of decades of debilitating deflation. The combination, says Mr. Takahashi, has required the nation to reach out to the younger generation.

Polls have showed that younger voters place a premium on economic issues and have more faith that Abenomics will lift wages than older voters, a fact not lost on Mr. Abe and his allies. “I think the younger generation harbors a vague sense of insecurity toward their future,” said Hiromasa Nakano, a lawmaker from Komeito, a junior partner in Mr. Abe’s ruling coalition.

A survey taken by Nippon Life Insurance Co. last year showed that 17% of those under 30 believed they wouldn’t receive any pension payments under Japan’s current pension plan, compared with less than 1% among those in their 60s.

Mr. Abe may also be betting that the younger generation is more open to his efforts to lift restrictions on Japan’s military by changing the country’s pacifist constitution, in place since the end of World War II. “Obviously the LDP thinks that constitutional revision could come down to votes on the margin and is betting that younger voters are less attached to the constitution than older voters,” said Tobias Harris, a Japan analyst at Teneo Intelligence.

‘I think the younger generation harbors a vague sense of insecurity toward their future.’

—Hiromasa Nakano, lawmaker

The young are in general less worked up about issues related to Japan’s wartime past, or its territorial disputes. Japan’s relationship with China and South Korea has worsened since Mr. Abe took power, but a government survey in October showed that those in their 20s harbored warmer feelings than people over 60 for Beijing and Seoul.

Yui Kobayashi, an 18-year-old high-school student, said she believed Japan, China and South Korea need to cooperate to find a peaceful resolution to the territorial issues, and said she was against Mr. Abe’s move to expand the role of the military. “I feel very scared when I imagine a future where me, my family and my friends may have to go to war,” said Ms. Kobayashi, who is active in the same youth group as Mr. Matsubayashi, Teen’s Rights Movement.

A poll taken by Kyodo News in August showed nearly 70% of those in their 20s and 30s opposed Mr. Abe’s plan to allow Japan to engage in collective self-defense, or coming to the aid of an ally under attack. But the poll indicated economic issues were a much higher priority for all age groups. Only 13% of those in their 20s and 30s expressed an interest in security policies.

A younger electorate could affect a number of social issues. Another Kyodo poll in September showed that those in their 20s were most supportive of promoting more women to senior positions. And according to a recent poll by the Asahi Shimbun newspaper, 60% to 70% of those in their 20s to 40s approve of moves to recognize same-sex marriages, compared with about a fifth of those 70 and older.

It isn’t clear how many newly eligible voters will actually cast a vote. A drop in voter turnout in Japan in recent years is especially pronounced among the young: Only 38% of voters in their 20s went to the polls in the 2012 general election, compared with 75% among those in their 60s.

Yui Kobayashi, right, asked young Japanese to vote in a mock election. Photo: Teen’s Rights Movement

And the broader demographic trend means the lower voting age will ultimately have limited impact. “A marginal increase in younger voters will do little to offset the power of retirees,” said Mr. Harris of Teneo Intelligence.

Sawa Isogai, a 19-year-old university student and a member of Ivote, a student organization promoting voter turnout, says that the change needs to be accompanied by better education.

“Teachers don’t discuss elections or the importance of voting at school; there’s a general lack of interest in politics among students,” she said.

Mr. Abe said Feb. 17 in parliament that the government would “take every opportunity” to promote awareness through cooperation with schools, election boards and local communities.

The bill is expected to take effect for upper-house elections in the summer of 2016—by which time Mr. Matsubayashi, who was snubbed by the politician with fliers, will have turned 18.

He now tries to steer conversations with classmates toward social issues and away from smartphone games.

“Everyone holds some kind of opinion on politics. It’s important to pull that out,” he said.

Japan’s Youth Stand to Gain Stronger Voice - WSJ