dadeechi

BANNED

- Joined

- Sep 12, 2015

- Messages

- 4,281

- Reaction score

- -8

- Country

- Location

How the map of Jammu and Kashmir could have been significantly different today

by Arjun Subramaniam

Published 14 hours ago.

Had India not accepted the cease-fire of 1948, much of the land that’s with Pakistan and China today may have been with India.

The 1947-'48 war with Pakistan was baptism by fire for independent India’s armed forces and, contrary to common perception, much of its contemporary DNA can be attributed to what emerged from the year long conflict.

As a white blanket of snow heralded the onset of winter and the bare Chinar trees and walnut groves sadly watched over the war, the times did not augur well for the Indian Army as operations slowed down. Further making the going tough for both Thimayya and Atma Singh was the fact that after due clearance from the Pakistan Army C-in-C Gen Frank Messervy, their divisions were now frontally engaged by a division each of the regular Pakistan Army (9th Frontier Division and 7th Pak Division).

Much to the frustration of their aggressive brigade commanders like Harbaksh Singh and Yadunath Singh, they would have to wait for the spring of ’49 to build up forces for any further offensive towards Mirpur, Kotli, Muzzafarabad and into the Northern Regions of J&K.

This was not to be, as Mountbatten pushed Nehru and the Pakistani political leadership to accept a UN brokered ceasefire on 31 Dec 1948 that left large portions of the Northern region, Kashmir Valley and Jammu Province in Pakistani hands. The military angle of this nudge was that had the Indian Army, supported by an increasingly confident Royal Indian Air Force, chosen to conduct their spring offensive along the Indus towards Gilgit and Skardu, the strategically important region may no longer have been a buffer that could be exploited by the British in the Great Game; a possibility, which they optimistically thought could be sustained for decades to come.

Pressured by the UN to settle for a ceasefire for almost a year after it had surprisingly moved the Security Council to intervene in the conflict in early ’48, the Indian government settled for a UN sponsored ceasefire on 1 Jan ’49.

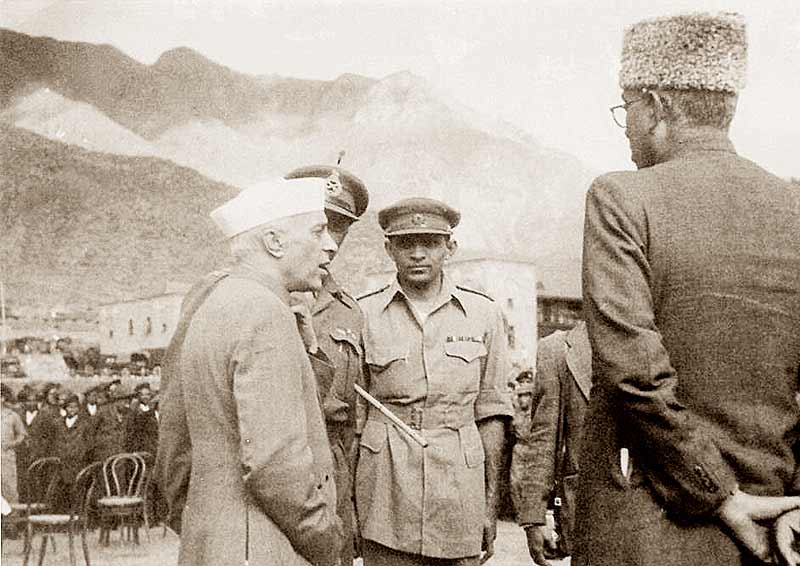

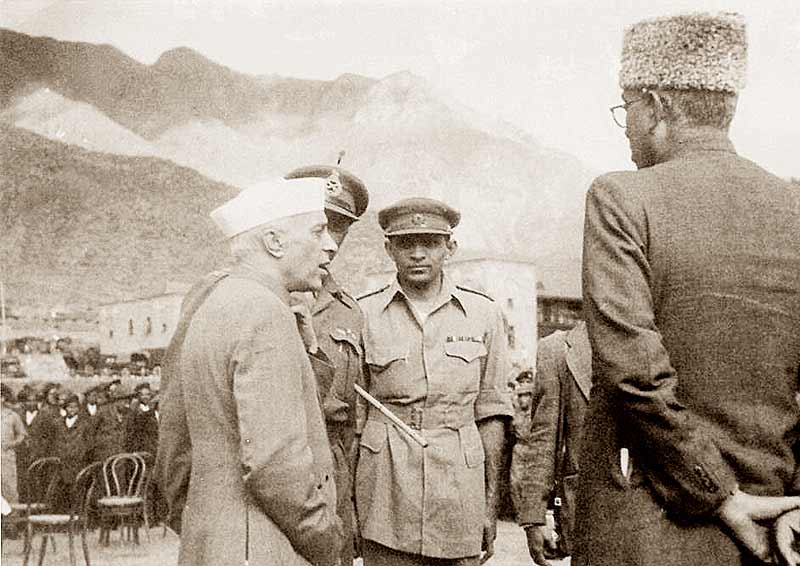

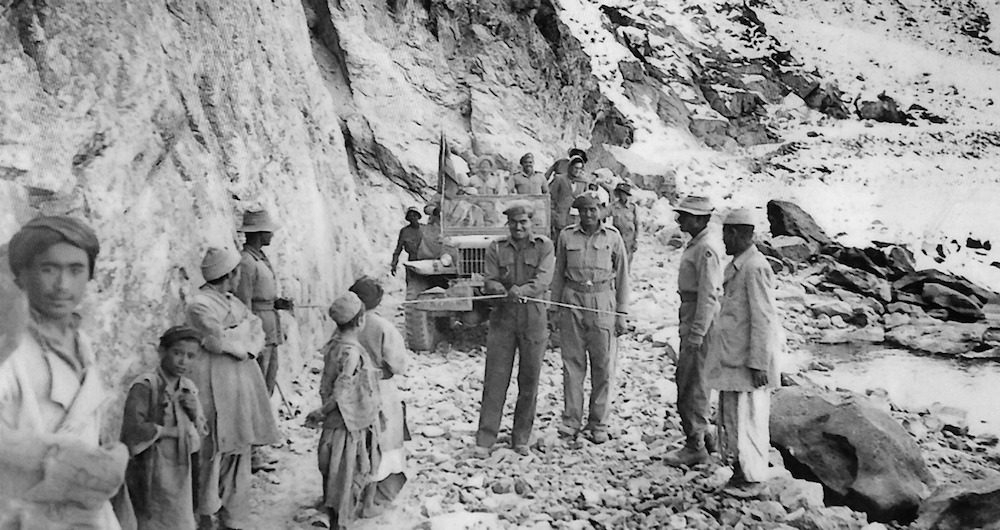

Jawaharlal Nehru and Sheikh Abdullah discussing military plans with Brigadier Mohammad Usman, Commander of 50 Para Brigade

However, the much anticipated plebiscite in Kashmir never happened. There were too many geographical pre-conditions that favoured Pakistan and by not being assertive enough about retaining control over areas like the Haji Pir pass, Gilgit and Skardu, India ceded operational advantage in the region to Pakistan. It would prove ominous in the years ahead, particularly when China started evincing keen interest in Ladakh.

If India had not accepted the UN brokered ceasefire, it would have built-up forces methodically through the winter as Lt Gen Cariappa had by then, taken complete charge of military operation. Nehru would have seen through the fog of war and Mountbatten, who, after initially sympathising with India, had started gravitating towards Pakistan as Indian military successes through 1948 pushed Pakistan on the back foot.

His assertive military commanders, like Thimayya and Atma Singh, would have impressed on him the need to go for the jugular and push the Pakistanis completely out of Kashmir. While this may not have been possible as the Pakistan Army would have fully joined in the fight, large tracts of territory in the Skardu region, Domel, Tithwal and Poonch areas could have been reclaimed by the Indian Army during a spring offensive in 1949, following which India may have accepted the ceasefire after getting assurances of further withdrawal from occupied territories.

Importantly, Shaksgam Valley would never have been ceded to China. All senior commanders of the time felt that had India stalled the ceasefire and built up forces for a spring offensive in 1949, the map of Jammu and Kashmir would have been significantly different today.

7-Dakotas of 12 Squadron – the saviours of Poonch

The 1947-48 war with Pakistan showcased a remarkably refreshing emerging ethos of the Indian Armed Forces: an ethos that transcended its colonial legacy and showcased its secular, multi-cultural and multi-ethnic flavor. A Sikh regiment was the first to be rushed in to defend a Muslim-majority province. Lt David, who charged in from the rear in his Daimler Armoured Car of 7 Cavalry and caused mayhem amongst the tribals at Shalateng, was a Christian.

Major Maurice Cohen, the young Signals officer who took part in the various battles that were fought in the Poonch sector, was a Jew. Brig Usman and Sqn Ldr Zafar Shah were Muslims who chose to stay in India despite direct approaches from Jinnah.

Mehar Singh was a fiery Sikh; Mickey Blake, the dashing flight commander of one of the Tempest squadrons who made all those daring forays over Skardu, was among the many Anglo-Indians who were decorated for their exploits in combat; Minoo Engineer, the Officer Commanding of 1 Wing (Srinagar) was a Parsi; and, best of all, the engineer regiment that built the track to Zozila in freezing temperature was a company from the Madras Engineering Regiment under the command of Major Thangaraju.

Many of these “Thambis” (most South Indians in the armed forces are affectionately called Thambi, which means “little brother”) had never seen snow in their lives! This is not to forget all the other ethnic communities who fought side-by-side – Kumaonis, Gorhkas, Jats, Ladakhis, Dogras, Marathas, Mahars, Rajputs, Coorgs, Mahars and many more. It truly was a spectacular show of unity in diversity.

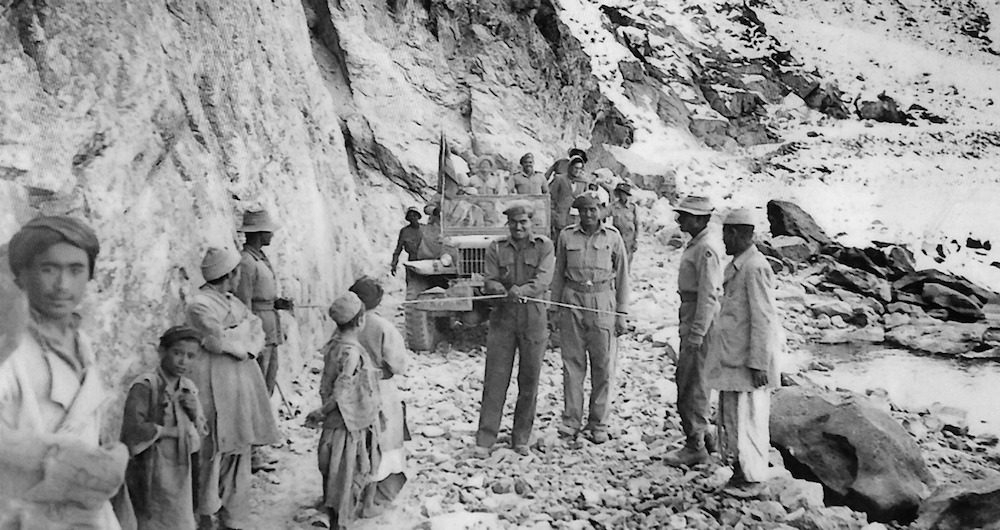

9-Major Thangaraju, Madras Engineering Regiment opening Zojila Pass 1948-2

The last lesson from this war which would have a bearing on future conflicts involving India was the fact that India as a country would always prefer restraint and caution when it came to using force as an instrument of statecraft. It would always prefer negotiations and diplomacy instead, revealing that as a nation it was more comfortable with articulating deterrence rather than pursuing coercion as a security strategy.

This singularly meant that it would employ its defence forces in a primarily defensive role, thereby exposing it to significant initial attrition before offering a befitting riposte. It is to the credit of India’s military leadership that it has respected this political strategy, albeit, at times, paying a heavy human price for it.

The brave words of Maj Somnath Sharma – “I shall not withdraw an inch but will fight to the last man and the last round” would ring true in many battles and encounters that India’s armed forces would fight in the years ahead to protect Indian democracy and sovereignty.

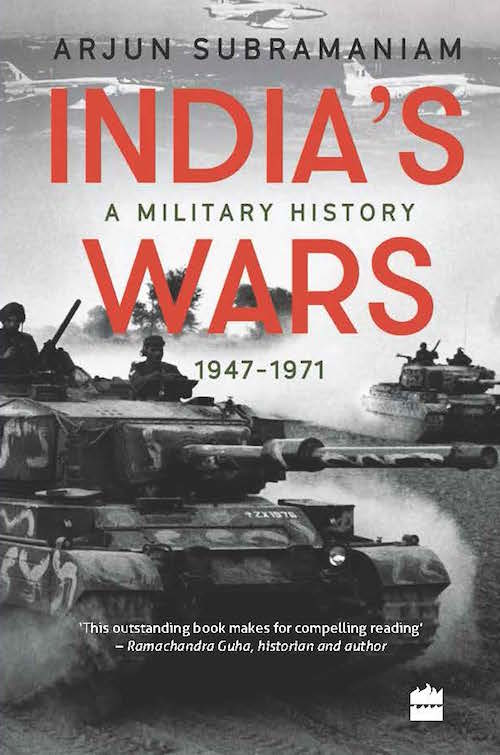

Excerpted with permission from India’s Wars: A Military History 1947-1971, Arjun Subramaniam, HarperCollins India.

http://scroll.in/bulletins/8/meet-f...he-consumer-at-the-center-of-their-businesses

by Arjun Subramaniam

Published 14 hours ago.

Had India not accepted the cease-fire of 1948, much of the land that’s with Pakistan and China today may have been with India.

The 1947-'48 war with Pakistan was baptism by fire for independent India’s armed forces and, contrary to common perception, much of its contemporary DNA can be attributed to what emerged from the year long conflict.

As a white blanket of snow heralded the onset of winter and the bare Chinar trees and walnut groves sadly watched over the war, the times did not augur well for the Indian Army as operations slowed down. Further making the going tough for both Thimayya and Atma Singh was the fact that after due clearance from the Pakistan Army C-in-C Gen Frank Messervy, their divisions were now frontally engaged by a division each of the regular Pakistan Army (9th Frontier Division and 7th Pak Division).

Much to the frustration of their aggressive brigade commanders like Harbaksh Singh and Yadunath Singh, they would have to wait for the spring of ’49 to build up forces for any further offensive towards Mirpur, Kotli, Muzzafarabad and into the Northern Regions of J&K.

This was not to be, as Mountbatten pushed Nehru and the Pakistani political leadership to accept a UN brokered ceasefire on 31 Dec 1948 that left large portions of the Northern region, Kashmir Valley and Jammu Province in Pakistani hands. The military angle of this nudge was that had the Indian Army, supported by an increasingly confident Royal Indian Air Force, chosen to conduct their spring offensive along the Indus towards Gilgit and Skardu, the strategically important region may no longer have been a buffer that could be exploited by the British in the Great Game; a possibility, which they optimistically thought could be sustained for decades to come.

Pressured by the UN to settle for a ceasefire for almost a year after it had surprisingly moved the Security Council to intervene in the conflict in early ’48, the Indian government settled for a UN sponsored ceasefire on 1 Jan ’49.

Jawaharlal Nehru and Sheikh Abdullah discussing military plans with Brigadier Mohammad Usman, Commander of 50 Para Brigade

However, the much anticipated plebiscite in Kashmir never happened. There were too many geographical pre-conditions that favoured Pakistan and by not being assertive enough about retaining control over areas like the Haji Pir pass, Gilgit and Skardu, India ceded operational advantage in the region to Pakistan. It would prove ominous in the years ahead, particularly when China started evincing keen interest in Ladakh.

If India had not accepted the UN brokered ceasefire, it would have built-up forces methodically through the winter as Lt Gen Cariappa had by then, taken complete charge of military operation. Nehru would have seen through the fog of war and Mountbatten, who, after initially sympathising with India, had started gravitating towards Pakistan as Indian military successes through 1948 pushed Pakistan on the back foot.

His assertive military commanders, like Thimayya and Atma Singh, would have impressed on him the need to go for the jugular and push the Pakistanis completely out of Kashmir. While this may not have been possible as the Pakistan Army would have fully joined in the fight, large tracts of territory in the Skardu region, Domel, Tithwal and Poonch areas could have been reclaimed by the Indian Army during a spring offensive in 1949, following which India may have accepted the ceasefire after getting assurances of further withdrawal from occupied territories.

Importantly, Shaksgam Valley would never have been ceded to China. All senior commanders of the time felt that had India stalled the ceasefire and built up forces for a spring offensive in 1949, the map of Jammu and Kashmir would have been significantly different today.

7-Dakotas of 12 Squadron – the saviours of Poonch

The 1947-48 war with Pakistan showcased a remarkably refreshing emerging ethos of the Indian Armed Forces: an ethos that transcended its colonial legacy and showcased its secular, multi-cultural and multi-ethnic flavor. A Sikh regiment was the first to be rushed in to defend a Muslim-majority province. Lt David, who charged in from the rear in his Daimler Armoured Car of 7 Cavalry and caused mayhem amongst the tribals at Shalateng, was a Christian.

Major Maurice Cohen, the young Signals officer who took part in the various battles that were fought in the Poonch sector, was a Jew. Brig Usman and Sqn Ldr Zafar Shah were Muslims who chose to stay in India despite direct approaches from Jinnah.

Mehar Singh was a fiery Sikh; Mickey Blake, the dashing flight commander of one of the Tempest squadrons who made all those daring forays over Skardu, was among the many Anglo-Indians who were decorated for their exploits in combat; Minoo Engineer, the Officer Commanding of 1 Wing (Srinagar) was a Parsi; and, best of all, the engineer regiment that built the track to Zozila in freezing temperature was a company from the Madras Engineering Regiment under the command of Major Thangaraju.

Many of these “Thambis” (most South Indians in the armed forces are affectionately called Thambi, which means “little brother”) had never seen snow in their lives! This is not to forget all the other ethnic communities who fought side-by-side – Kumaonis, Gorhkas, Jats, Ladakhis, Dogras, Marathas, Mahars, Rajputs, Coorgs, Mahars and many more. It truly was a spectacular show of unity in diversity.

9-Major Thangaraju, Madras Engineering Regiment opening Zojila Pass 1948-2

The last lesson from this war which would have a bearing on future conflicts involving India was the fact that India as a country would always prefer restraint and caution when it came to using force as an instrument of statecraft. It would always prefer negotiations and diplomacy instead, revealing that as a nation it was more comfortable with articulating deterrence rather than pursuing coercion as a security strategy.

This singularly meant that it would employ its defence forces in a primarily defensive role, thereby exposing it to significant initial attrition before offering a befitting riposte. It is to the credit of India’s military leadership that it has respected this political strategy, albeit, at times, paying a heavy human price for it.

The brave words of Maj Somnath Sharma – “I shall not withdraw an inch but will fight to the last man and the last round” would ring true in many battles and encounters that India’s armed forces would fight in the years ahead to protect Indian democracy and sovereignty.

Excerpted with permission from India’s Wars: A Military History 1947-1971, Arjun Subramaniam, HarperCollins India.

http://scroll.in/bulletins/8/meet-f...he-consumer-at-the-center-of-their-businesses