khair_ctg

FULL MEMBER

- Joined

- May 22, 2013

- Messages

- 1,083

- Reaction score

- 2

- Country

- Location

I wonder if it was actually real events on the ground, or a few politically motivated articles that shaped the perception of many in the world regarding the 1971 Indian aggression. here it says these articles are remembered fondly, but its more like the fascists force people to 'remember' things they did not experience and that did not happen.

@MBI Munshi @Al-zakir @Md Akmal @bongbang @Loki @Saiful Islam @Khalid Newazi @genmirajborgza786 @Armstrong @Tameem @aazidane @asad71 @idune @Luffy 500 @Bilal9 @Rajput_Pakistani @DESERT FIGHTER @monitor

_________________________

Bangladesh war: The article that changed history

By Mark Dummett

BBC News

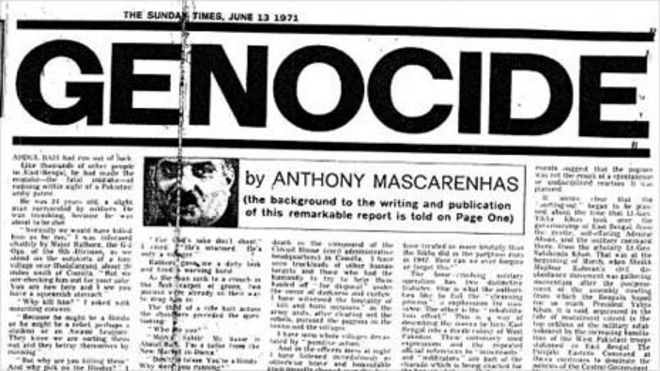

On 13 June 1971, an article in the UK's Sunday Times exposed the brutality of Pakistan's suppression of the Bangladeshi uprising. It forced the reporter's family into hiding and changed history.

Abdul Bari had run out of luck. Like thousands of other people in East Bengal, he had made the mistake - the fatal mistake - of running within sight of a Pakistani patrol. He was 24 years old, a slight man surrounded by soldiers. He was trembling because he was about to be shot.

So starts one of the most influential pieces of South Asian journalism of the past half century.

Written by Anthony Mascarenhas, a Pakistani reporter, and printed in the UK's Sunday Times, it exposed for the first time the scale of the Pakistan army's brutal campaign to suppress its breakaway eastern province in 1971.

Nobody knows exactly how many people were killed, but certainly a huge number of people lost their lives. Independent researchers think that between 300,000 and 500,000 died. The Bangladesh government puts the figure at three million.

The strategy failed, and Bangladeshis are now celebrating the 40th anniversary of the birth of their country. Meanwhile, the first trial of those accused of committing war crimes has recently begun in Dhaka.

Anthony Mascarenhas

Anthony Mascarenhas was 'just a very good reporter', recalls Harold Evans

There is little doubt that Mascarenhas' reportage played its part in ending the war. It helped turn world opinion against Pakistan and encouraged India to play a decisive role.

Prime Minister Indira Gandhi told the then editor of the Sunday Times, Harold Evans, that the article had shocked her so deeply it had set her "on a campaign of personal diplomacy in the European capitals and Moscow to prepare the ground for India's armed intervention," he recalled.

Not that this was ever Mascarenhas' intention. He was, Evans wrote in his memoirs, "just a very good reporter doing an honest job".

He was also very brave. Pakistan, at the time, was run by the military, and he knew that he would have to get himself and his family out of the country before the story could be published - not an easy task in those days.

"His mother always told him to stand up and speak the truth and be counted," Mascarenhas's widow, Yvonne, recalled (he died in 1986). "He used to tell me, put a mountain before me and I'll climb it. He was never daunted."

A map of Pakistan before the 1971 war

When the war in what was then East Pakistan broke out in March 1971, Mascarenhas was a respected journalist in Karachi, the main city in the country's dominant western wing, on good terms with the country's ruling elite. He was a member of the city's small community of Goan Christians, and he and Yvonne had five children.

Foreign journalists had already been expelled, and Pakistan was also keen to publicise atrocities committed by the other side. Awami League supporters had massacred tens of thousands of civilians whose loyalty they suspected, a war crime that is still denied by many today in Bangladesh.

Eight journalists, including Mascarenhas, were given a 10-day tour of the province. When they returned home, seven of them duly wrote what they were told to.

But one of them refused.

Yvonne Mascarenhas remembers him coming back distraught: "I'd never seen my husband looking in such a state. He was absolutely shocked, stressed, upset and terribly emotional," she says, speaking from her home in west London.

"He told me that if he couldn't write the story of what he'd seen he'd never be able to write another word again."

Clearly it would not be possible to do so in Pakistan. All newspaper articles were checked by the military censor, and Mascarenhas told his wife he was certain he would be shot if he tried.

Pretending he was visiting his sick sister, Mascarenhas then travelled to London, where he headed straight to the Sunday Times and the editor's office.

Bangladesh independence war, 1971

Indians and Bengali guerrillas fought in support of East Pakistan

Evans remembers him in that meeting as having "the bearing of a military man, square-set and moustached, but appealing, almost soulful eyes and an air of profound melancholy".

"He'd been shocked by the Bengali outrages in March, but he maintained that what the army was doing was altogether worse and on a grander scale," Evans wrote.

Mascarenhas told him he had been an eyewitness to a huge, systematic killing spree, and had heard army officers describe the killings as a "final solution".

Evans promised to run the story, but first Yvonne and the children had to escape Karachi.

They had agreed that the signal for them to start preparing for this was a telegram from Mascarenhas saying that "Ann's operation was successful".

Yvonne remembers receiving the message at three the next morning. "I heard the telegram man bang at my window and I woke up my sons and I was: 'Oh my gosh, we have to go to London.' It was terrifying. I had to leave everything behind.

"We could only take one suitcase each. We were crying so much it was like a funeral," she says.

To avoid suspicion, Mascarenhas had to return to Pakistan before his family could leave. But as Pakistanis were only allowed one foreign flight a year, he then had to sneak out of the country by himself, crossing by land into Afghanistan.

The day after the family was reunited in their new home in London, the Sunday Times published his article, under the headline "Genocide".

'Betrayal'

It is such a powerful piece of reporting because Mascarenhas was clearly so well trusted by the Pakistani officers he spent time with.

I have witnessed the brutality of 'kill and burn missions' as the army units, after clearing out the rebels, pursued the pogrom in the towns and villages.

I have seen whole villages devastated by 'punitive action'.

And in the officer's mess at night I have listened incredulously as otherwise brave and honourable men proudly chewed over the day's kill.

'How many did you get?' The answers are seared in my memory.

This was one of the most significant articles written on the war

-Mofidul Huq, Liberation War Museum

His article was - from Pakistan's point of view - a huge betrayal and he was accused of being an enemy agent. It still denies its forces were behind such atrocities as those described by Mascarenhas, and blames Indian propaganda.

However, he still maintained excellent contacts there, and in 1979 became the first journalist to reveal that Pakistan had developed nuclear weapons.

In Bangladesh, of course, he is remembered more fondly, and his article is still displayed in the country's Liberation War Museum.

"This was one of the most significant articles written on the war. It came out when our country was cut off, and helped inform the world of what was going on here," says Mofidul Huq, a trustee of the museum.

His family, meanwhile, settled into life in a new and colder country.

"People were so serious in London and nobody ever talked to us," Yvonne Mascarenhas remembers. "We were used to happy, smiley faces, it was all a bit of a change for us after Karachi. But we never regretted it."

@MBI Munshi @Al-zakir @Md Akmal @bongbang @Loki @Saiful Islam @Khalid Newazi @genmirajborgza786 @Armstrong @Tameem @aazidane @asad71 @idune @Luffy 500 @Bilal9 @Rajput_Pakistani @DESERT FIGHTER @monitor

_________________________

Bangladesh war: The article that changed history

By Mark Dummett

BBC News

On 13 June 1971, an article in the UK's Sunday Times exposed the brutality of Pakistan's suppression of the Bangladeshi uprising. It forced the reporter's family into hiding and changed history.

Abdul Bari had run out of luck. Like thousands of other people in East Bengal, he had made the mistake - the fatal mistake - of running within sight of a Pakistani patrol. He was 24 years old, a slight man surrounded by soldiers. He was trembling because he was about to be shot.

So starts one of the most influential pieces of South Asian journalism of the past half century.

Written by Anthony Mascarenhas, a Pakistani reporter, and printed in the UK's Sunday Times, it exposed for the first time the scale of the Pakistan army's brutal campaign to suppress its breakaway eastern province in 1971.

Nobody knows exactly how many people were killed, but certainly a huge number of people lost their lives. Independent researchers think that between 300,000 and 500,000 died. The Bangladesh government puts the figure at three million.

The strategy failed, and Bangladeshis are now celebrating the 40th anniversary of the birth of their country. Meanwhile, the first trial of those accused of committing war crimes has recently begun in Dhaka.

Anthony Mascarenhas

Anthony Mascarenhas was 'just a very good reporter', recalls Harold Evans

- July 1928: Born in Goa

- 1930s: Educated in Karachi

- June 1971: Exposes war crimes in East Pakistan that alter international opinion

- 1972: Wins international journalism awards

- 1979: Reports that Pakistan has developed nuclear weapons

There is little doubt that Mascarenhas' reportage played its part in ending the war. It helped turn world opinion against Pakistan and encouraged India to play a decisive role.

Prime Minister Indira Gandhi told the then editor of the Sunday Times, Harold Evans, that the article had shocked her so deeply it had set her "on a campaign of personal diplomacy in the European capitals and Moscow to prepare the ground for India's armed intervention," he recalled.

Not that this was ever Mascarenhas' intention. He was, Evans wrote in his memoirs, "just a very good reporter doing an honest job".

He was also very brave. Pakistan, at the time, was run by the military, and he knew that he would have to get himself and his family out of the country before the story could be published - not an easy task in those days.

"His mother always told him to stand up and speak the truth and be counted," Mascarenhas's widow, Yvonne, recalled (he died in 1986). "He used to tell me, put a mountain before me and I'll climb it. He was never daunted."

A map of Pakistan before the 1971 war

When the war in what was then East Pakistan broke out in March 1971, Mascarenhas was a respected journalist in Karachi, the main city in the country's dominant western wing, on good terms with the country's ruling elite. He was a member of the city's small community of Goan Christians, and he and Yvonne had five children.

Foreign journalists had already been expelled, and Pakistan was also keen to publicise atrocities committed by the other side. Awami League supporters had massacred tens of thousands of civilians whose loyalty they suspected, a war crime that is still denied by many today in Bangladesh.

Eight journalists, including Mascarenhas, were given a 10-day tour of the province. When they returned home, seven of them duly wrote what they were told to.

But one of them refused.

Yvonne Mascarenhas remembers him coming back distraught: "I'd never seen my husband looking in such a state. He was absolutely shocked, stressed, upset and terribly emotional," she says, speaking from her home in west London.

"He told me that if he couldn't write the story of what he'd seen he'd never be able to write another word again."

Clearly it would not be possible to do so in Pakistan. All newspaper articles were checked by the military censor, and Mascarenhas told his wife he was certain he would be shot if he tried.

Pretending he was visiting his sick sister, Mascarenhas then travelled to London, where he headed straight to the Sunday Times and the editor's office.

Bangladesh independence war, 1971

- Civil war erupts in Pakistan, pitting the West Pakistan army against East Pakistanis demanding autonomy and later independence

- Fighting forces an estimated 10 million East Pakistani civilians to flee to India

- In December, India invades East Pakistan in support of the East Pakistani people

- Pakistani army surrenders at Dhaka and its army of more than 90,000 become Indian prisoners of war

- East Pakistan becomes the independent country of Bangladesh on 16 December 1971

- Exact number of people killed is unclear - Bangladesh says it is three million but independent researchers say it is up to 500,000 fatalities

Indians and Bengali guerrillas fought in support of East Pakistan

Evans remembers him in that meeting as having "the bearing of a military man, square-set and moustached, but appealing, almost soulful eyes and an air of profound melancholy".

"He'd been shocked by the Bengali outrages in March, but he maintained that what the army was doing was altogether worse and on a grander scale," Evans wrote.

Mascarenhas told him he had been an eyewitness to a huge, systematic killing spree, and had heard army officers describe the killings as a "final solution".

Evans promised to run the story, but first Yvonne and the children had to escape Karachi.

They had agreed that the signal for them to start preparing for this was a telegram from Mascarenhas saying that "Ann's operation was successful".

Yvonne remembers receiving the message at three the next morning. "I heard the telegram man bang at my window and I woke up my sons and I was: 'Oh my gosh, we have to go to London.' It was terrifying. I had to leave everything behind.

"We could only take one suitcase each. We were crying so much it was like a funeral," she says.

To avoid suspicion, Mascarenhas had to return to Pakistan before his family could leave. But as Pakistanis were only allowed one foreign flight a year, he then had to sneak out of the country by himself, crossing by land into Afghanistan.

The day after the family was reunited in their new home in London, the Sunday Times published his article, under the headline "Genocide".

'Betrayal'

It is such a powerful piece of reporting because Mascarenhas was clearly so well trusted by the Pakistani officers he spent time with.

I have witnessed the brutality of 'kill and burn missions' as the army units, after clearing out the rebels, pursued the pogrom in the towns and villages.

I have seen whole villages devastated by 'punitive action'.

And in the officer's mess at night I have listened incredulously as otherwise brave and honourable men proudly chewed over the day's kill.

'How many did you get?' The answers are seared in my memory.

This was one of the most significant articles written on the war

-Mofidul Huq, Liberation War Museum

His article was - from Pakistan's point of view - a huge betrayal and he was accused of being an enemy agent. It still denies its forces were behind such atrocities as those described by Mascarenhas, and blames Indian propaganda.

However, he still maintained excellent contacts there, and in 1979 became the first journalist to reveal that Pakistan had developed nuclear weapons.

In Bangladesh, of course, he is remembered more fondly, and his article is still displayed in the country's Liberation War Museum.

"This was one of the most significant articles written on the war. It came out when our country was cut off, and helped inform the world of what was going on here," says Mofidul Huq, a trustee of the museum.

His family, meanwhile, settled into life in a new and colder country.

"People were so serious in London and nobody ever talked to us," Yvonne Mascarenhas remembers. "We were used to happy, smiley faces, it was all a bit of a change for us after Karachi. But we never regretted it."

swimming is a must to join the army..

swimming is a must to join the army..