艹艹艹

SENIOR MEMBER

- Joined

- Jul 7, 2016

- Messages

- 5,149

- Reaction score

- 0

- Country

- Location

Xinjiang’s millennial entrepreneurs make the most of the Internet age

By Yin Lu and Zhang Xinyuan Source:Global Times Published: 2016/7/4 23:53:01

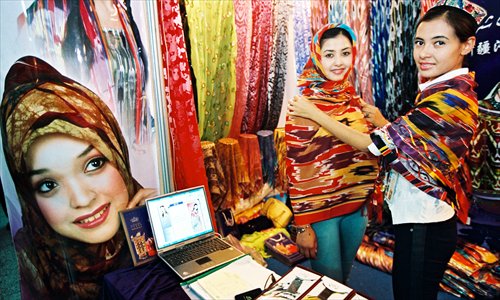

A young saleswoman sells scarfs to a customer at the Urumqi Fair inXinjiang. Photo: CFP

Young entrepreneurs from the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region are exploring new business areas such as e-commerce, online education, digital solutions, the Internet of Things and more. They are utilizing their talents in business hubs all over the country, and some are even planning to expand overseas.

While Xinjiang is positioned as one of the "core areas" of the "One Belt, One Road" initiative, its young people are striving to realize their dreams, taking advantage of the resources and opportunities offered by the Internet age.

Abdulhabir Muhammad learnt about the importance of the Internet the hard way.

Young entrepreneur Abdulhabir Muhammad poses for the camera. Photo: Li Hao/GT

Abdulhabir Muhammad, 26, from Aksu, founder of A.B.U. Education. Photo: Li Hao/GT

In March, he got sick after going from school to school in Xinjiang for a whole month to give speeches and talk to high school and college students about going overseas for further education. He decided that there must be a better way to reach people.

"In the past, I thought I should be a traditional type of educator, but there are limits to that. Then I realized how important it is to make use of the Internet," he said. Muhammad graduated from the State University of New York at Binghamton with an MBA in 2014. Muhammad founded A.B.U. Education this year, which provides language training and consultation services to Xinjiang students who want to study overseas.

Over the last three months, Muhammad has been working on promoting his firm on the Internet, after researching China's major social media platforms, messaging apps, and real-time streaming websites.

On top of launching a WeChat public account, he has also started discussions about overseas studies on SinaWeibo which ended up trending. He does online streaming, talking about topics related to overseas education and life, such as introducing US universities and high schools to his audience. He also offers online classes on Xinjiang's first English-language radio channel, Voice of A.B.U., which is available on multiple online platforms and apps.

"Now I feel like I am adapting to the requirements of this age," he said.

His efforts have proven to be effective, and now his Weibo page has more than 120,000 followers. The demographics of his fan base are gradually changing too. In the beginning about 60 percent of his followers and audience online were Xinjiang natives, but as he has started to stream in Chinese and English the majority of his new followers are from other parts of China.

Muhammad is very encouraged by the fact that many of his followers are from outside Xinjiang, and some schools in other regions are now asking him to deliver speeches. Therefore, he is successfully shifting his focus to a broader market, targeting students across the entire country.

Muhammad would also like to create a platform that offers online courses taught by professors overseas to help students in Xinjiang who can't afford to go abroad.

"We want to bring these courses to Xinjiang and other western regions, in English, Chinese, Uyghur and other local languages," he said. However, his biggest objective is to serve overseas returnees who are from Xinjiang and other western regions of China, starting from building connections among the community as well as collecting and sharing information regarding job hunting.

"I hope the students who go overseas will come back to contribute to our economy," he said.

Adil Mamattura, 26, from Kashgar, founder of Xinjiang Nut Cake Prince Company. Photo: Courtesy of Adil Mamattura

A 2012 incident that involved a vendor selling Xinjiang nut cake - a traditional street snack made of nuts, sweets and glutinous rice - prompted Mamattura to start his own nut cake business. He was then a student at the Changsha University of Science and Technology, Central China's Hunan Province. At the end of that year, a Uyghur nut cake vendor who got into a fight with a customer over the price of his wares was paid 160,000 yuan ($24,080) for cakes damaged in the fight, raising controversy over inter-ethnic relations. Mamattura thought that this incident would give people a bad impression of his homeland's traditional snack, so decided to promote the cake online.

Now, four years later, the monthly sales volume of his nut cake company has reached 3 to 6 million yuan. These staggering numbers are the result of how he has used the Internet to promote nut cake, his Nut Cake Prince brand and himself.

Mamattura regularly makes videos and posts them on social media to show how nut cake is produced. He believes transparency - key in a nation that has been hit again and again by food scandals - will make customers trust his product.

"WeChat is a platform that we attach great importance to right now. Our account has over 1.2 million fans, and we rely on fan marketing, like if our fans invite other people to follow our account we send them some nut cake as a gift," Mamattura said.

Mamattura is also trying to use the live streaming trend to expand his business. He plans to promote his new line of cantaloupes by going to Turpan and using apps such as Yingke to show the cantaloupe fields, how they are grown and the transportation process, to prove the cantaloupes are of good quality.

"I did not deliberately make myself an Internet celebrity, but since customers recognize my face and trust me, I will use this advantage to help more customers know and trust our brand," Mamattura said.

Mamattura is planning to make Xinjiang nut cake go international, and challenge the status of Snickers as one of world's leading sweet, nutty snacks. "At a frisbee event in Shanghai, some of the foreigners had a bite of Xinjiang nut cake, and they said it's more delicious and healthy than Snickers. Since it's made of a variety of different nuts, it's very nutritious and can replenish one's energy quickly," Mamattura said.

Their comments got Mamattura thinking. Xinjiang nut cake is soft, and easily influenced by temperature, and thus has short expiration date. This makes it difficult to sell in large quantities and for people to carry it around with them. He is now developing a new recipe to make it more crispy and give it a longer shelf life.

"I plan to launch the new product as an energy bar next year, in small and fashionable packaging that will attract more young customers," Mamattura said.

Ailikemu Abujili, 28, from Hami, founder and CEO of Hangzhou Qiming E-commercial Company Ltd. Photo: Courtesy of Ailikemu Abujili

Ailikemu Abujili owns a company that sells toys and men's sportswear online, based in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province.

Starting from a small, humble apartment he rented in November 2014 where all his staff live and work, the company now has a team of seven people and boosts a monthly turnover of $120,000. His sales are mostly made overseas, mainly to the US, through online platforms including Ebay, Amazon and AliExpress, e-commerce giant Alibaba's cross-board marketplace.

However, prior to this, like many other Chinese college graduates of his age, Abujili went through a period of not knowing what to do with his life after he graduated with a degree in aerial transport from a Ukrainian college.

Finally, he decided that e-commerce is the future of business.

So he chose Hangzhou, where e-commerce giant Alibaba is located, due to its comparatively lower logistics costs and the subsidies provided by the local government to start-ups.

Abujili even got his household registration moved to Hangzhou. Now he is also planning to open offices in Shanghai, due to its Free Trade Area, and Shenzhen, South China's Guangdong Province.

Abujili believes he's found the right place for himself, and he hopes more young people from Xinjiang will join this industry and try their luck in different cities in the country.

Originally from Hami, a city known for its sweet melons, he thinks simply being known as a place where good fruit is grown is far from what the region's young people want their countrymen to think about Xinjiang.

"Many people still think that business owners from Xinjiang are no more than restauranteurs, or those who run barbecue stands and fruit shops," he said. "I would like to let them know that we are capable of making breakthroughs in e-commerce too."

Arfat Anvar, 24, from Gulja, founder of YammiGO. Photo: Li Hao/GT

Arfat Anvar wants to make sure that people all over the country who want halal foods are able to quickly receive their freshnang, a traditional type of Xinjiang flatbread, wrapped in tinfoil in a box with the logo of their company hand written on it.

With a diploma in software engineering from Beijing's North China Electric Power University, Anvar has recently been trying to promote his services on social media, such as giving prizes to Net users who participate in discussions about his brand. With the website and app they are about to launch soon, individuals and retailers will be able to purchase halal foods ranging from dried fruits and mutton jerky to biscuits and energy bars from YammiGO.

His primary targets right now are college students from Xinjiang studying in other parts of China, as he understands how hard it is for them to eat religiously suitable food. "When I was in school, I found it hard to find halal foods," he said.

While there are shops on bigger retailing platforms such as taobao.com, and many halal food companies have developed their own apps or WeChat accounts to sell their products, there's no other company like Anvar's which sells a variety of different halal foods on one platform.

Anvar said that his background and connections in Xinjiang have been an advantage for him. "I know where to find the most authentic halal food. I know if I want jujube, I go to Hotan (in Xinjiang) and directly buy them from a local peasant."

His ambition is to build his brand into an international success story like Amazon. Starting in Malaysia, Anvar is trying to build connections and cooperate with foreign major food companies, and represent them in China.

Anvar encourages young Uyghurs who want to get out of their comfort zone and start something new, to not to be afraid to take their first step.

"Some people might not be confident enough, thinking whether or not a humble young person from Xinjiang is able to start up a good business in other parts of the country. I want to let them know that you absolutely can. Just go ahead and build a team and start going," Anvar said.

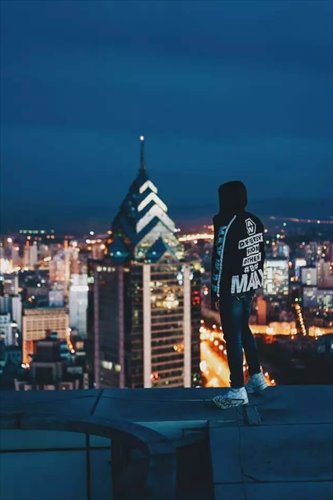

Skyline in Urumqi, Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Photo: CFP

http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/992281.shtml

By Yin Lu and Zhang Xinyuan Source:Global Times Published: 2016/7/4 23:53:01

A young saleswoman sells scarfs to a customer at the Urumqi Fair inXinjiang. Photo: CFP

Young entrepreneurs from the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region are exploring new business areas such as e-commerce, online education, digital solutions, the Internet of Things and more. They are utilizing their talents in business hubs all over the country, and some are even planning to expand overseas.

While Xinjiang is positioned as one of the "core areas" of the "One Belt, One Road" initiative, its young people are striving to realize their dreams, taking advantage of the resources and opportunities offered by the Internet age.

Abdulhabir Muhammad learnt about the importance of the Internet the hard way.

Young entrepreneur Abdulhabir Muhammad poses for the camera. Photo: Li Hao/GT

Abdulhabir Muhammad, 26, from Aksu, founder of A.B.U. Education. Photo: Li Hao/GT

In March, he got sick after going from school to school in Xinjiang for a whole month to give speeches and talk to high school and college students about going overseas for further education. He decided that there must be a better way to reach people.

"In the past, I thought I should be a traditional type of educator, but there are limits to that. Then I realized how important it is to make use of the Internet," he said. Muhammad graduated from the State University of New York at Binghamton with an MBA in 2014. Muhammad founded A.B.U. Education this year, which provides language training and consultation services to Xinjiang students who want to study overseas.

Over the last three months, Muhammad has been working on promoting his firm on the Internet, after researching China's major social media platforms, messaging apps, and real-time streaming websites.

On top of launching a WeChat public account, he has also started discussions about overseas studies on SinaWeibo which ended up trending. He does online streaming, talking about topics related to overseas education and life, such as introducing US universities and high schools to his audience. He also offers online classes on Xinjiang's first English-language radio channel, Voice of A.B.U., which is available on multiple online platforms and apps.

"Now I feel like I am adapting to the requirements of this age," he said.

His efforts have proven to be effective, and now his Weibo page has more than 120,000 followers. The demographics of his fan base are gradually changing too. In the beginning about 60 percent of his followers and audience online were Xinjiang natives, but as he has started to stream in Chinese and English the majority of his new followers are from other parts of China.

Muhammad is very encouraged by the fact that many of his followers are from outside Xinjiang, and some schools in other regions are now asking him to deliver speeches. Therefore, he is successfully shifting his focus to a broader market, targeting students across the entire country.

Muhammad would also like to create a platform that offers online courses taught by professors overseas to help students in Xinjiang who can't afford to go abroad.

"We want to bring these courses to Xinjiang and other western regions, in English, Chinese, Uyghur and other local languages," he said. However, his biggest objective is to serve overseas returnees who are from Xinjiang and other western regions of China, starting from building connections among the community as well as collecting and sharing information regarding job hunting.

"I hope the students who go overseas will come back to contribute to our economy," he said.

Adil Mamattura, 26, from Kashgar, founder of Xinjiang Nut Cake Prince Company. Photo: Courtesy of Adil Mamattura

A 2012 incident that involved a vendor selling Xinjiang nut cake - a traditional street snack made of nuts, sweets and glutinous rice - prompted Mamattura to start his own nut cake business. He was then a student at the Changsha University of Science and Technology, Central China's Hunan Province. At the end of that year, a Uyghur nut cake vendor who got into a fight with a customer over the price of his wares was paid 160,000 yuan ($24,080) for cakes damaged in the fight, raising controversy over inter-ethnic relations. Mamattura thought that this incident would give people a bad impression of his homeland's traditional snack, so decided to promote the cake online.

Now, four years later, the monthly sales volume of his nut cake company has reached 3 to 6 million yuan. These staggering numbers are the result of how he has used the Internet to promote nut cake, his Nut Cake Prince brand and himself.

Mamattura regularly makes videos and posts them on social media to show how nut cake is produced. He believes transparency - key in a nation that has been hit again and again by food scandals - will make customers trust his product.

"WeChat is a platform that we attach great importance to right now. Our account has over 1.2 million fans, and we rely on fan marketing, like if our fans invite other people to follow our account we send them some nut cake as a gift," Mamattura said.

Mamattura is also trying to use the live streaming trend to expand his business. He plans to promote his new line of cantaloupes by going to Turpan and using apps such as Yingke to show the cantaloupe fields, how they are grown and the transportation process, to prove the cantaloupes are of good quality.

"I did not deliberately make myself an Internet celebrity, but since customers recognize my face and trust me, I will use this advantage to help more customers know and trust our brand," Mamattura said.

Mamattura is planning to make Xinjiang nut cake go international, and challenge the status of Snickers as one of world's leading sweet, nutty snacks. "At a frisbee event in Shanghai, some of the foreigners had a bite of Xinjiang nut cake, and they said it's more delicious and healthy than Snickers. Since it's made of a variety of different nuts, it's very nutritious and can replenish one's energy quickly," Mamattura said.

Their comments got Mamattura thinking. Xinjiang nut cake is soft, and easily influenced by temperature, and thus has short expiration date. This makes it difficult to sell in large quantities and for people to carry it around with them. He is now developing a new recipe to make it more crispy and give it a longer shelf life.

"I plan to launch the new product as an energy bar next year, in small and fashionable packaging that will attract more young customers," Mamattura said.

Ailikemu Abujili, 28, from Hami, founder and CEO of Hangzhou Qiming E-commercial Company Ltd. Photo: Courtesy of Ailikemu Abujili

Ailikemu Abujili owns a company that sells toys and men's sportswear online, based in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province.

Starting from a small, humble apartment he rented in November 2014 where all his staff live and work, the company now has a team of seven people and boosts a monthly turnover of $120,000. His sales are mostly made overseas, mainly to the US, through online platforms including Ebay, Amazon and AliExpress, e-commerce giant Alibaba's cross-board marketplace.

However, prior to this, like many other Chinese college graduates of his age, Abujili went through a period of not knowing what to do with his life after he graduated with a degree in aerial transport from a Ukrainian college.

Finally, he decided that e-commerce is the future of business.

So he chose Hangzhou, where e-commerce giant Alibaba is located, due to its comparatively lower logistics costs and the subsidies provided by the local government to start-ups.

Abujili even got his household registration moved to Hangzhou. Now he is also planning to open offices in Shanghai, due to its Free Trade Area, and Shenzhen, South China's Guangdong Province.

Abujili believes he's found the right place for himself, and he hopes more young people from Xinjiang will join this industry and try their luck in different cities in the country.

Originally from Hami, a city known for its sweet melons, he thinks simply being known as a place where good fruit is grown is far from what the region's young people want their countrymen to think about Xinjiang.

"Many people still think that business owners from Xinjiang are no more than restauranteurs, or those who run barbecue stands and fruit shops," he said. "I would like to let them know that we are capable of making breakthroughs in e-commerce too."

Arfat Anvar, 24, from Gulja, founder of YammiGO. Photo: Li Hao/GT

Arfat Anvar wants to make sure that people all over the country who want halal foods are able to quickly receive their freshnang, a traditional type of Xinjiang flatbread, wrapped in tinfoil in a box with the logo of their company hand written on it.

With a diploma in software engineering from Beijing's North China Electric Power University, Anvar has recently been trying to promote his services on social media, such as giving prizes to Net users who participate in discussions about his brand. With the website and app they are about to launch soon, individuals and retailers will be able to purchase halal foods ranging from dried fruits and mutton jerky to biscuits and energy bars from YammiGO.

His primary targets right now are college students from Xinjiang studying in other parts of China, as he understands how hard it is for them to eat religiously suitable food. "When I was in school, I found it hard to find halal foods," he said.

While there are shops on bigger retailing platforms such as taobao.com, and many halal food companies have developed their own apps or WeChat accounts to sell their products, there's no other company like Anvar's which sells a variety of different halal foods on one platform.

Anvar said that his background and connections in Xinjiang have been an advantage for him. "I know where to find the most authentic halal food. I know if I want jujube, I go to Hotan (in Xinjiang) and directly buy them from a local peasant."

His ambition is to build his brand into an international success story like Amazon. Starting in Malaysia, Anvar is trying to build connections and cooperate with foreign major food companies, and represent them in China.

Anvar encourages young Uyghurs who want to get out of their comfort zone and start something new, to not to be afraid to take their first step.

"Some people might not be confident enough, thinking whether or not a humble young person from Xinjiang is able to start up a good business in other parts of the country. I want to let them know that you absolutely can. Just go ahead and build a team and start going," Anvar said.

Skyline in Urumqi, Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Photo: CFP

http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/992281.shtml