Lord ZeN

SENIOR MEMBER

- Joined

- Jul 24, 2014

- Messages

- 2,483

- Reaction score

- 15

- Country

- Location

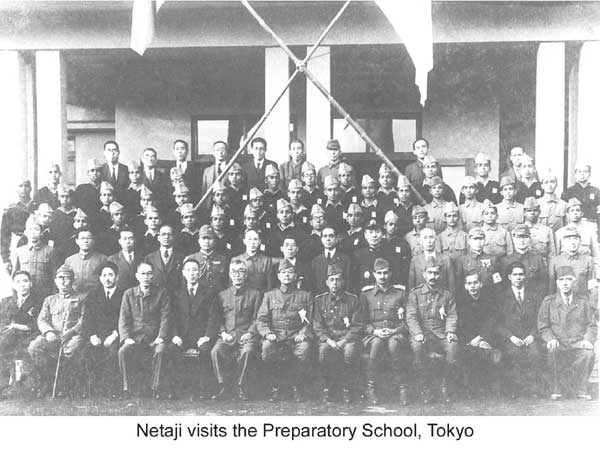

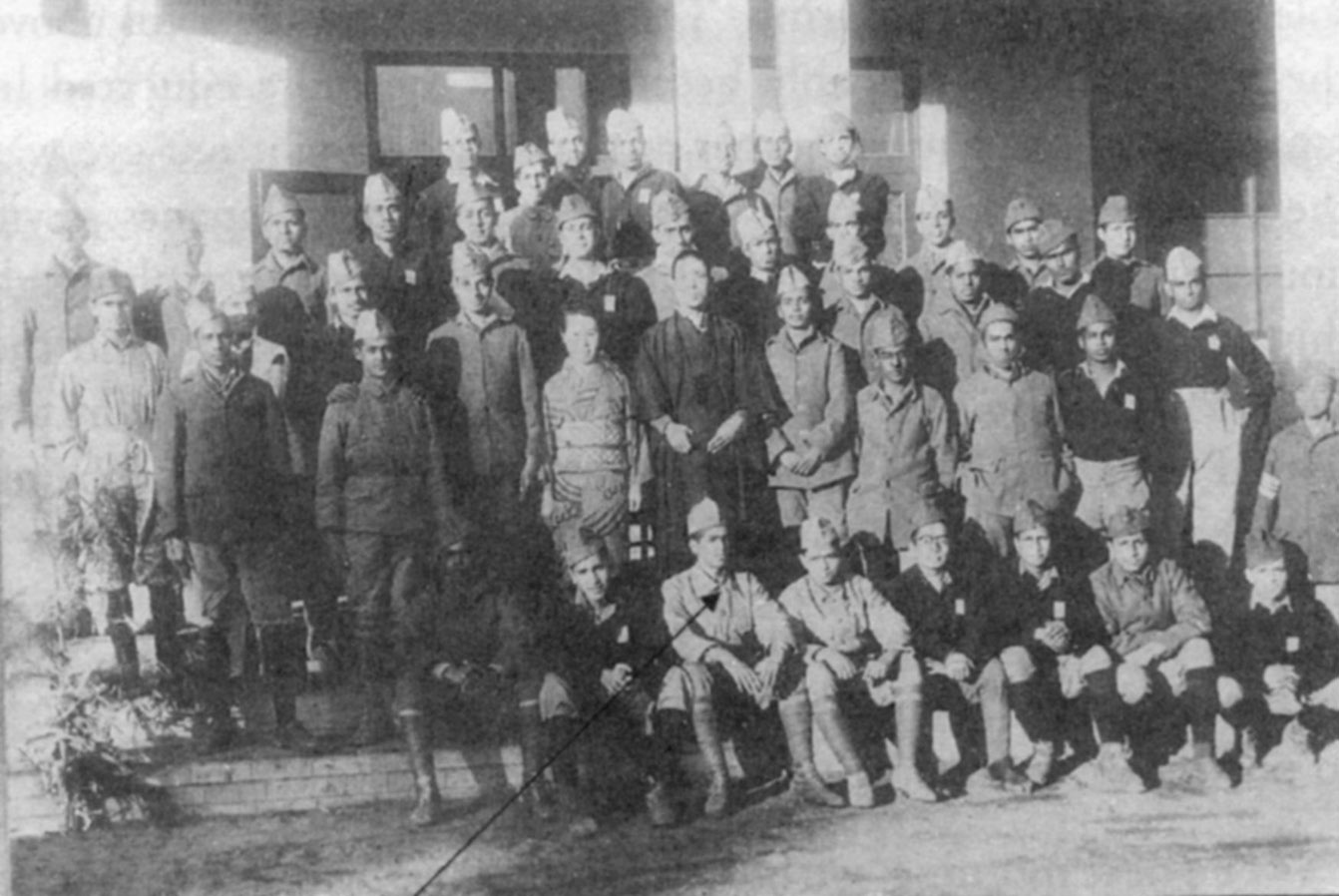

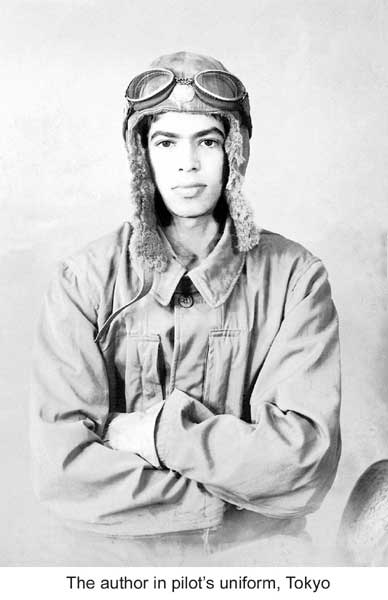

Excerpt from Burma to Japan with Azad Hind

Ramesh Benegal, recipent of the Maha Vir Chakra, was born in Burma and was seventeen when the Japanese captured British-occupied Burma. He tells this extraordinary, first-person story of his career with the Indian National Army in Burma and Japan in the year from 1941 to 1945

Our first impression—and it turned out to be a lasting one—was that the people in Kyushu were quite different from the Japanese we had encountered in the occupied territories of Burma, Malaya and the Philippines.

They were so refined, polite and gentle that one could not associate them with the rough, abusive front-line soldiers of the Japanese army. The naval officers were a cut above the army soldiers, probably because only the more educated in Japan joined the navy. Another aspect which caught our eye was the cleanliness of the town, the streets, the neat Japanese-style houses and the well-laid-out parks. We also noticed that, although this was a large town, there were hardly any restaurants, and the shelves in the large number of shops were bare. Japan had already started to tighten its belt and every necessity of life was now being rationed under central control.

We stayed in a hotel for a day and were kitted out with breeches-like trousers tied at the ankles, boots and a woolen coat to protect us against the weather which was fast turning cold.

The next morning, we boarded the train which was to take us to Tokyo and the Preparatory School. The train passed through lovely countryside and we were filled with wonder when it went through a long tunnel under the sea.

We had heard so much about Tokyo and were not disappointed when we arrived there. The bustling city had one of the best local train systems in the world. We were told that we could set our watches by the times when these trains arrived and left. All signboards were in Japanese and although we were conversant with the language by now and knew how to read Katakana, the basic entry-level alphabet, we could not understand a single notice.

The representatives of the batch which had gone before us were part of the reception committee which greeted us on arrival, and we were happy to meet some of our own for a change. They gave us contradictory reports on life in the Preparatory School, known as Koa Do Gakuin, and we did not know which version to believe—the good one or the bad one.

When we reached the school, we were formally received by the housemaster, who was responsible for our physical training and discipline. He looked grim and spoke through the side of his mouth. After his welcome speech, we were allotted rooms. Mine was on the ground floor right next to the entrance to the building. The room looked warm enough with a bed on one side, a cupboard at the other end and a writing table and chair against the only window. Getting a room to oneself after what we had been through was the height of luxury. But little did we know that the timetable of this Borstal-like institute would hardly give us any time in our rooms.The school itself was set in very picturesque surroundings. It consisted of three blocks in a truncated ‘U’. Our block had fifty rooms, 25 on the ground floor and an equal number on the first floor. The middle part of the ‘U’ had the classrooms and a large dining room, while the other part of the ‘U’ had about 20 rooms which housed a group of eight cadets from Thailand. They were not only indisciplined but also very rude to the school authorities. They never attended classes, never came to PT sessions and perpetually fussed about the food and the quality of medical attention. Although they were so close to our billets, we were quite clearly segregated from them. I was unable to understand why their country had sent them here. They only ended up making their lives miserable—and everyone else’s as well.

We were given a day to rest and recuperate from our journey and then the routine started. Reveille at five in the morning, a three-mile run to a park in the vicinity, a fifteen-minute halt and a run back to school; then a five-minute break followed by ten minutes’ PT, all this in temperatures below zero, and on occasions even when it was snowing. We had half an hour for ablutions and then breakfast consisting of a bowl of rice and a bowl of shiru. As a special case, we were given a bottle of pasteurised milk. We loved this. Then we had classes until noon. Lunch was a repetition of the earlier meal and was sometimes supplemented with fish. After this, we had classes until four. Then a cup of Japanese tea without sugar. (Sugar was such a rare commodity that a couple of teaspoons of it were served once a year on Emperor Meiji’s birthday with that day’s tea.) Then we changed into our PT kit and had compulsory games until six, a half-hour break for a change of clothes, dinner at 6.30—a repetition of the morning menu, sometimes embellished by pickled radish. We had compulsory study under supervision until eight and then it was lights off at ten.

The two hours after study were the only time we could call our own and were spent in chat and making friends within the group. Sundays were free after the morning run and PT, but we had to spend a lot of time washing our clothes and keeping our rooms spotlessly clean for the next day’s inspection. Booking out was not allowed and any visit out was only in groups and under supervision. The only entertainment we enjoyed was skating (without skates!), whenever the pond in front of the main building froze.

When we lost Bishan Singh that fateful day, our number had been reduced by one. To make up the intended number of 45, a new cadet called Aktar Ahmed was chosen and sent to join us. It was good to have him.

There were a few flatterers who would visit the housemaster and his wife when they were free in the evening and listen to his tiresome sermons. It was strongly recommended that we take turns to attend these meetings. It was only after I went a few times that I realised that there was a good side to these visits. The housemaster’s wife would serve us green tea and things to eat, and this made a change from the meagre food we were served in the school. The hard part was sitting for an hour and pretending to listen to the housemaster’s stories. He was well-meaning, though.

A Japanese film division group visited us and filmed our activities at the school. It was something like ‘A day in the life of a foreign cadet’. The film was shot in colour and when it was shown to us, we could not believe that it was us or that it was our school. Everything looked grand in colour. Even the dining scene with the food spread on the table looked like a banquet.

Ramesh Benegal, recipent of the Maha Vir Chakra, was born in Burma and was seventeen when the Japanese captured British-occupied Burma. He tells this extraordinary, first-person story of his career with the Indian National Army in Burma and Japan in the year from 1941 to 1945

Our first impression—and it turned out to be a lasting one—was that the people in Kyushu were quite different from the Japanese we had encountered in the occupied territories of Burma, Malaya and the Philippines.

They were so refined, polite and gentle that one could not associate them with the rough, abusive front-line soldiers of the Japanese army. The naval officers were a cut above the army soldiers, probably because only the more educated in Japan joined the navy. Another aspect which caught our eye was the cleanliness of the town, the streets, the neat Japanese-style houses and the well-laid-out parks. We also noticed that, although this was a large town, there were hardly any restaurants, and the shelves in the large number of shops were bare. Japan had already started to tighten its belt and every necessity of life was now being rationed under central control.

We stayed in a hotel for a day and were kitted out with breeches-like trousers tied at the ankles, boots and a woolen coat to protect us against the weather which was fast turning cold.

The next morning, we boarded the train which was to take us to Tokyo and the Preparatory School. The train passed through lovely countryside and we were filled with wonder when it went through a long tunnel under the sea.

We had heard so much about Tokyo and were not disappointed when we arrived there. The bustling city had one of the best local train systems in the world. We were told that we could set our watches by the times when these trains arrived and left. All signboards were in Japanese and although we were conversant with the language by now and knew how to read Katakana, the basic entry-level alphabet, we could not understand a single notice.

The representatives of the batch which had gone before us were part of the reception committee which greeted us on arrival, and we were happy to meet some of our own for a change. They gave us contradictory reports on life in the Preparatory School, known as Koa Do Gakuin, and we did not know which version to believe—the good one or the bad one.

When we reached the school, we were formally received by the housemaster, who was responsible for our physical training and discipline. He looked grim and spoke through the side of his mouth. After his welcome speech, we were allotted rooms. Mine was on the ground floor right next to the entrance to the building. The room looked warm enough with a bed on one side, a cupboard at the other end and a writing table and chair against the only window. Getting a room to oneself after what we had been through was the height of luxury. But little did we know that the timetable of this Borstal-like institute would hardly give us any time in our rooms.The school itself was set in very picturesque surroundings. It consisted of three blocks in a truncated ‘U’. Our block had fifty rooms, 25 on the ground floor and an equal number on the first floor. The middle part of the ‘U’ had the classrooms and a large dining room, while the other part of the ‘U’ had about 20 rooms which housed a group of eight cadets from Thailand. They were not only indisciplined but also very rude to the school authorities. They never attended classes, never came to PT sessions and perpetually fussed about the food and the quality of medical attention. Although they were so close to our billets, we were quite clearly segregated from them. I was unable to understand why their country had sent them here. They only ended up making their lives miserable—and everyone else’s as well.

We were given a day to rest and recuperate from our journey and then the routine started. Reveille at five in the morning, a three-mile run to a park in the vicinity, a fifteen-minute halt and a run back to school; then a five-minute break followed by ten minutes’ PT, all this in temperatures below zero, and on occasions even when it was snowing. We had half an hour for ablutions and then breakfast consisting of a bowl of rice and a bowl of shiru. As a special case, we were given a bottle of pasteurised milk. We loved this. Then we had classes until noon. Lunch was a repetition of the earlier meal and was sometimes supplemented with fish. After this, we had classes until four. Then a cup of Japanese tea without sugar. (Sugar was such a rare commodity that a couple of teaspoons of it were served once a year on Emperor Meiji’s birthday with that day’s tea.) Then we changed into our PT kit and had compulsory games until six, a half-hour break for a change of clothes, dinner at 6.30—a repetition of the morning menu, sometimes embellished by pickled radish. We had compulsory study under supervision until eight and then it was lights off at ten.

The two hours after study were the only time we could call our own and were spent in chat and making friends within the group. Sundays were free after the morning run and PT, but we had to spend a lot of time washing our clothes and keeping our rooms spotlessly clean for the next day’s inspection. Booking out was not allowed and any visit out was only in groups and under supervision. The only entertainment we enjoyed was skating (without skates!), whenever the pond in front of the main building froze.

When we lost Bishan Singh that fateful day, our number had been reduced by one. To make up the intended number of 45, a new cadet called Aktar Ahmed was chosen and sent to join us. It was good to have him.

There were a few flatterers who would visit the housemaster and his wife when they were free in the evening and listen to his tiresome sermons. It was strongly recommended that we take turns to attend these meetings. It was only after I went a few times that I realised that there was a good side to these visits. The housemaster’s wife would serve us green tea and things to eat, and this made a change from the meagre food we were served in the school. The hard part was sitting for an hour and pretending to listen to the housemaster’s stories. He was well-meaning, though.

A Japanese film division group visited us and filmed our activities at the school. It was something like ‘A day in the life of a foreign cadet’. The film was shot in colour and when it was shown to us, we could not believe that it was us or that it was our school. Everything looked grand in colour. Even the dining scene with the food spread on the table looked like a banquet.

Last edited: